2022 in retrospect

Synopsis : A brief look back over the season just finishing. Climate is what we expect, weather is what we get {{1}}. And we got a lot of it.

Introduction

The winter solstice last Wednesday seems an appropriate time for a brief overview of the season that has just finished. The 21st of December is the shortest day of the year. Perhaps surprisingly, because of the equation of time (the difference between solar clocks and our clocks) it is not the day with the latest sunrise and earliest sunset. For my location, these are on the 29th and 14th of December respectively.

Not only is it the 21st the shortest day of the year, it’s also – ironic considering the freezing weather the UK had last week – only the beginning of astronomical winter, which lasts until the 20th of March.

However, for beekeepers, the 21st is significant for two reasons; increasing amounts of daylight and the fact that many colonies are likely to now have started rearing brood for the coming season. Longer, warmer {{2}}, days will make foraging possible – both in terms of there being forage available and it being warm enough for the bees to fly.

And, to survive next winter – as well as hopefully reproduce (swarm) next summer – the colony needs to start rearing brood now.

It takes bees to make bees. A colony cannot collect sufficient nectar and pollen to rear large amounts of brood, or keep large amounts of brood warm, unless there are lots of bees already in the colony. Therefore, a small {{3}} broodless colony will restart brood rearing slowly, ramping brood production up as more bees – and pollen and nectar – become available.

A gentle reminder

Most of my colonies have been broodless from about the second week of November but the majority are now brood rearing again. ‘Most’ and ’the majority’ as there are a few hives that appear to have never stopped, going by the debris that has fallen through the open mesh floor onto the Varroa tray.

There are others that appear to have not yet have restarted.

When the colony is either completely broodless (or has the minimum level of brood) the proportion of the total number of Varroa mites in the hive that are phoretic are at a maximum. That is the time to treat with dribbled or vaporised oxalic acid … not at some convenient time in mid-January when you belatedly remember.

My colonies were treated with oxalic acid on the 13th of November and, after an initial mite drop that confirmed that the treatment had worked, during recent monitoring have not dropped another mite in the last 21 days.

The fewer mites in the colony when brood rearing starts, the lower the peak mite level will be later in the season (all other things being equal i.e. brood breaks, swarming, rate of brood rearing etc.). If the levels remain reasonably low it will not be necessary to intervene until late summer, after the honey harvest occurs and before the bulk of the winter bees are being reared. This is why I treat in the winter.

The alternative is you start the season with high mite levels and end up with damagingly high mite levels before or during the summer nectar flow, all of which makes everything more complicated than it needs to be.

But enough thinking about next season, how did this season go?

Pretty well 🙂 .

Latitude and longitude

I’ve got bees on either side of Scotland. They are at about the same latitude and the closest east and west coast apiaries are only separated by 110 miles as the bee flies. Nevertheless, the season is completely different on opposite coasts.

I think this is due to three interacting factors:

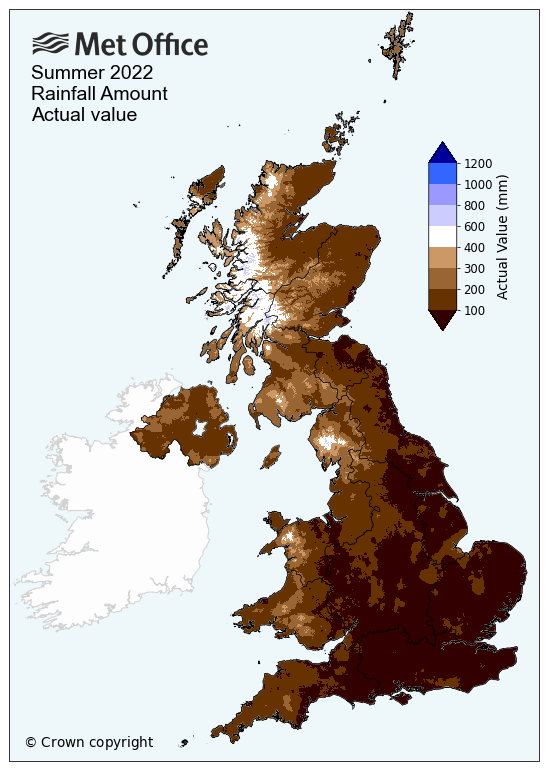

- climate; the west coast is generally warm(ish) and wet {{4}} whereas the east coast is much drier and generally has colder winter temperatures and hotter summer temperatures. For comparison, at the time of writing, Fife had a fraction under 1 metre of rain for the year with minimum and maximums of -10°C and 30°C, in contrast on the west coast we’ve had 2 metres of rain and temperatures of -3°C and 25°C. However, as will become clearer when I discuss queen rearing, these basic facts obscure some significant differences in climate, and have consequences for beekeeping.

- forage; the east coast is rich agricultural land and there’s usually oil seed rape available early in the season. This gives the bees a huge boost. In contrast, the west coast has scrubby woodland and hedgerows with natural forage but almost no farming and precious few gardens (and the deer eat everything anyway 🙁 ). The main honey-producing forage on the west coast is heather.

- bees; my Fife bees are homegrown ’Heinz’ local mongrels {{5}} with a little bit of native black bees in their dim and distant past. On the west coast the bees are native Apis mellifera mellifera. These are much more frugal, build up more slowly in Spring, swarm much later and will continue to forage in miserable weather.

Winter

I do almost no practical beekeeping during astronomical winter (reminder … 21st December to 20th March). My colonies are treated for Varroa before winter starts (see above) and colony inspections don’t start until after winter ends.

East coast

I checked colony weights periodically – about once a month – by hefting the hive. Where needed I added additional blocks of fondant. I don’t bother messing about adding 250 g at a time but just place 2 kg blocks in a food container inverted over the top bars. The weather is too cold for regular foraging and you don’t want a break in rearing the important early season brood.

I added Varroa trays for a month from late January and the Varroa drop was (reassuringly) exceedingly low., and non-existent in the best hives. Remember, these were treated with oxalic acid three months earlier and brood rearing was building up strongly. Towards the end of this winter period colonies were foraging freely and building brace comb up into the inverted food trays, now emptied of fondant.

West coast

My west coast bees have no Varroa. I still periodically add a tray under the hives to see what falls through and to monitor brood rearing. Other than adding a block of fondant to a couple of hives I did nothing at all with them until well into April.

Spring

Spring felt as though it started later than usual. Cuckoos were a week or so later than normal in arriving, as were house martins and swallows. Unusually, grasshopper warblers didn’t arrive at all on the west coast. However, although these phenological signs suggested a late spring, the bees had been busy.

East coast

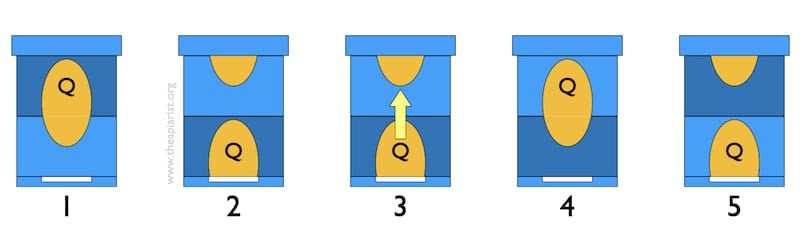

Most of my colonies are in single National boxes. It suits the bees and it suits me. Most consequently need swarm control, but that’s OK. It’s an opportunity to requeen them, it allows the production of a spare nuc or two and – timed correctly {{6}} – the queenless ‘half’ collects a good surplus of honey.

But, one or two are in double brood boxes.

I tend to rotate these as a means of controlling swarming, or at least attempting to. The queen tends to work in the upper brood box so, once this is more or less packed, I switch it with the lower box. Inevitably this breaks the brood nest which many consider a poor beekeeping practice.

However, the queen moves up again, filling the empty space ‘above’ her. By the time the upper box is full of brood, much of the lower box has emerged and I can rotate the boxes again.

Neither of the colonies I did this with this season needed additional swarm control {{7}}. Both ended the year with the same queen they’d started with.

Interestingly – at least it is to me – one of these queens had been destined for replacement very early in the season. In the first 2-3 inspections I’d noted some followers and overly-defensive behaviour.

On the 1st of May I’d scribbled ”Not nice bees – requeen ASAP” in my notes. However, the box switching distracted me (and her), made inspections quick and easy, and I had no spare queens anyway. By June the colony was no longer defensive and they remained calm and pleasant bees for the rest of the season.

If there is a lesson to this anecdote I’m not sure what it is 😉 .

West coast

After a fantastic March and April the weather took a turn for the worse. It rained on all but 5 days of May and the average temperature never exceeded 18°C. Much of the early season forage – primarily a variety of willows and abundant gorse – had finished and most colonies needed feeding. To encourage brood rearing I fed thin syrup and – for some colonies – pollen sub patties.

I’ve got a lot to learn about keeping bees here on the west coast. Both the climate and the available forage – at least until the heather flowers – are less good than on the other side of the country.

As a consequence, and in contrast to Fife, I only started swarm control on the west coast in the last couple days of astronomical spring (which ends on the summer solstice).

The busy part of the season was still ahead.

Summer

Astronomical summer runs from the 21st of June until the 23rd of September. This is the period with the second honey crop on the east coast and the heather crop (what little there was of it) on the west.

East coast

The majority of new east coast queens got mated, clipped and marked in late June and early July. Looking through my notes while preparing this post I see that a couple are still recorded as ‘NN’ … this means that, for whatever reason, I’ve found a laying queen (or know one is present) but have yet to get around to marking her.

At this time of the season the boxes are bursting with bees and, with a new queen and the risk of swarming much diminished (to say nothing of the heavy supers and high temperatures) my enthusiasm to scrabble through the box looking for her is non-existent less than it should be.

I can always hear a little voice saying ”She’ll be much easier to find next April …” 😉 .

The summer honey crop was exceptionally good. Unusually I had a couple of hives with 5 supers and one – in the shed – barely fitted under the rafters.

For the first time I had one of my clearer boards blocked with bees from the supers. This is clearly something I’ll have to look out for in the future, though I’m still not really sure why this particular hive got blocked. The board had only been in for about 18 hours, there was a deep lower rim to the clearer and no more than four supers.

Honey extraction was the usual tedious and messy process. Other than the sheer quantity, the only thing notable was that, considering the relatively dry summer on the east coast, the water content of the honey was – at about 18% or so for many buckets – higher than expected.

Or perhaps my refractometer is poorly calibrated 🙁 .

West coast

Until late August the weather on the west coast was very poor. Rearing queens was tricky; several rounds of cells were torn down, presumably because the colony was thinking ”Are you daft? Nothing is further from our mind than new queens … have you any more syrup?”

Cells that did reach maturity were placed in mini-nucs for mating, or used for requeening splits from other colonies.

And that’s when the problems started.

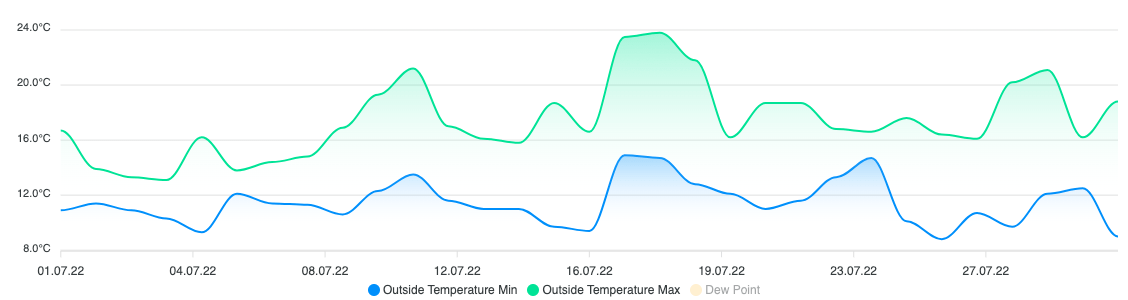

Although I had reasonable numbers of drones, helped by most colonies having a frame of drone foundation added back in April, queen mating was a protracted and fraught process. The weather in July was terrible with a lot of rain (~150 mm for the month, about 25% of what I’d expect for the year on the east coast) and only 3-4 days when the temperature exceeded 20°C.

All my queens did eventually get mated but, by golly, they took their time. A couple that emerged on the 15th of July were laying by the 26th of August … but had no sealed brood yet. This wasn’t unusual. These were getting worryingly close to the age at which they were too old to mate.

In one colony, the day I discovered the mated queen there was also evidence of a small amount of laying workers with widely scattered drone brood in worker cells. Fortunately, her brood rearing soon suppressed laying worker activity {{8}} and the colony ‘survived’. However, it will be next season before I can tell how well these queens were mated and I remain concerned that some may fail overwinter.

The heather honey crop eventually arrived in the three weeks of good weather before mid-September which pretty-much rescued the season.

Autumn

I usually do more beekeeping in September and early October than I do in August. The preparation for winter (which still seems a long way off, particularly if the weather is good) is critical and cannot be delayed.

East coast

Apivar strips went into all the Fife colonies on the same day that I started winter feeding and removed the honey supers (which this year was the last few days of August). Over the next 2-3 weeks I monitor the Varroa drop to get an idea of the infestation level.

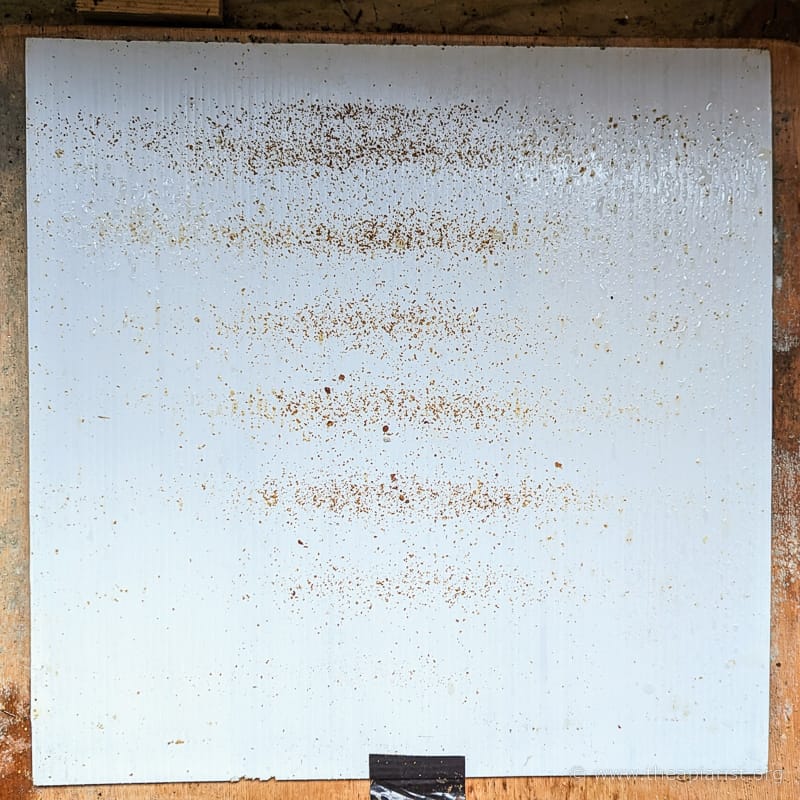

Gone are the days when I count every mite … it’s now usually a case of few/some/lots. However, I also photograph the trays, clean them and replace them ready for the next visit. I then look again at the photos on a big monitor in the lengthening evenings with a large glass of shiraz, so have a pretty fair idea the numbers associated with my few/some/lots categories.

I’m well aware of the numbers of bees that drift between colonies, and equally aware how these distribute mites and the viruses they carry. However, even hives as ‘cheek by jowl’ as those in my bee shed showed markedly different infestation levels.

Fortunately, very few colonies exhibited high mite drops during treatment. However, I think the gross discrepancies in mite levels (I’m assuming the %age of mites killed per colony as similar) tell me two things:

- the principle of just monitoring one sentinel colony per apiary is flawed. If your sentinel has a low mite load you could be missing colonies with dangerously high mite levels. Conversely, you could ‘over-treat’ colonies – intervening when it’s not needed – if your sentinel colony had a high mite load.

- these colonies with high mite loads, presumably exposed to similar levels of drifting etc., may not have desirable genetics (as far as mite control is concerned) and should probably be excluded from future queen rearing.

Fondant was finished by early October and – other than the November OA treatment – it was all over for the year.

West coast

There’s even less to do in the autumn on the west coast. These bees don’t have Varroa so no miticides are needed. The majority of the hives and nucs were packed with stores from the heather (so explaining the small amounts of honey I extracted 🙁 ) but still received a few kilograms of fondant to top them up for the long winter ahead.

As an aside, the heather honey wasn’t extracted (via the even messier crush and strain method) until late November and the water content was a very respectable 14-15%. Or perhaps my refractometer is poorly calibrated 🙁 .

At the last colony checks (late September) most colonies still had good levels of brood. The good late season weather and the heather has given them a real boost and they looked very good going into the winter.

Since then they’ve been out foraging on late season pollen. Unusually the weather was mild and dry enough for them to forage on the ivy and they were very busy through the warm first half of November.

But since then it’s all gone very quiet. Other than check the straps are secure for the inevitable winter gales, there’s now nothing to do until at least late March (or probably April).

Season’s Greetings

It was Oscar Wilde who said that ”Conversation about the weather is the last refuge of the unimaginative” so I’ll stop there 😉 .

For beekeepers in northern latitudes, it’s not quite ‘all or nothing’, but the difference between the busy summer season and the quiet of the winter is very marked. But there are still things to do.

I’ll be spending the next few weeks:

- building stuff for the season ahead.

- making some interesting blended honeys … both as a way to reduce the high water content of some of the honey from this season, and to eke out some of the limited amounts of heather honey I got this year.

- having another (likely abortive) attempt at making palatable mead.

- drinking coffee, spending time with family and friends, and doing all sorts of non-beekeeping things to keep me busy until the weather warms and it all starts again next year 🙂 .

Wherever you are, and whatever you’re doing, Season’s Greetings …

{{1}}: Mark Twain

{{2}}: Some way off, but they’re on the way.

{{3}}: And the colony will already be a lot smaller than it was in the autumn, and will continue to shrink for the next couple of months.

{{4}}: Not wet(ish) … just wet.

{{5}}: 57 varieties.

{{6}}: Or just dumb luck.

{{7}}: And, no, neither swarmed.

{{8}}: Or, more accurately, the open brood pheromone.

Join the discussion ...