Dancing in the City

Beekeeping is an increasingly popular pastime. Since ~84% of the UK population live in urban areas (up from ~70% in 1950’s) it is not unsurprising that the number of hives kept in cities is increasing.

Of course, not everyone who lives in a town or city keeps their bees in the back garden. When I lived in the Midlands I lived on a small estate that was indisputably ‘urban’, although there was farmland within sight {{1}}. My bees were on the nearby farmland and I just kept a few mating nucs and a bait hive in the back garden {{2}}.

I kept my bees in the farmland because {{3}} I reasoned that there were both larger amounts and a greater range of forage available for them there.

But I was probably wrong.

It wouldn’t be the first time, and it certainly won’t be the last.

Too many bees?

Before discussing urban bees and forage in more detail I’ll digress a minute to mention the suggestions that the inexorable rise and rise of urban beekeeping is threatening our native pollinators.

Actually … more than suggestions.

There are a number of scientific reports and reviews that indicate that urban beekeeping harms – by outcompeting – native pollinators like solitary bees. A recent report by the Royal Botanic Gardens at Kew states:

‘Campaigns encouraging people to save bees have resulted in an unsustainable proliferation in urban beekeeping. This approach only saves one species of bee, the honeybee, with no regard for how honeybees interact with other, native species.’

‘In some places, such as London, so many people have established urban hives that the honeybee populations are threatening other bee species.’

Our bees (Apis mellifera) are generalists. They are not particularly well adapted to any flower or nectar/pollen source.

They are equal opportunists.

Individually, there are many solitary bee species or non-hymenopteran pollinators, that are ‘better’ adapted. They pollinate more efficiently, or collect more nectar, faster.

But honey bees arrive in the environment mob handed.

Thousands of them.

Actually, tens or hundreds of thousands of them if there are several hives in an apiary. They are a formidable force and can easily outcompete other pollinators that are either solitary or only live in small colonies.

Save the bees, save humanity

When you see the phrase “Save the bees” what it usually means is save the honey bees.

What it should be encouraging is “Save anything but the honey bees, because they don’t need saving … actually, there are possibly too many of them altogether”.

But that’s a lot less catchy … and it won’t let the supermarket, or food manufacturer or whatever, illustrate their campaign with cute photos of pollen-laden honey bees returning to quaint white-painted WBC hives in some sort of idyllic rural scene {{4}}.

I suppose a photo of a honey bee would be better than drawing of a wasp though … which is what the NRDC used for a (mis)information campaign on CCD (colony collapse disorder) a few years ago.

D’oh!

Anyway … saving the bees is usually “greenwash” or bee-washing as it was termed by MacIvor and Packer in a 2015 paper on bee hotels {{5}}.

I’ll return to this topic, and urban beekeeping, later in the winter {{6}}.

The Town mouse bees and the Country mouse bees

Where was I?

Oh yes, my – as will shortly be clear – incorrect assumption that country bees have access to more diverse and richer sources of forage than their poor relatives living in the town.

There are many sorts of countryside and many sorts of urban environments.

A hive in an intensively farmed arable landscape could be located in hundreds of acres of wheat fields, where all of the hedgerows were grubbed up years ago and replaced – if they weren’t just removed altogether – with barbed wire {{7}}.

How different is that environment to the ‘concrete jungle’ of a modern city?

Surely that must be a terrible environment for bees?

In contrast, the suburban sprawl that surrounds most cities is possibly a good place for bees to live. Lots of neat little gardens, each {{8}} with a profusion of flowering plants, each chosen to provide vibrant colour for a much longer period than native plants.

And I’m sure we can all think of forage-rich rural environments. Here the bees gorge on early crocus, then gorse, willow, oil seed rape, clover, lime, blackberry, fireweed and himalayan balsam, before finishing the season will full crops and corbiculae from the ivy.

Now, in a recent publication {{9}} scientists have compared the forage available to town and country bees, and the results are quite surprising.

Let the bees tell you

If you live in a country with enlightened right to roam laws (like Scotland) you could wander around the countryside recording all the forage available to bees.

But the laws in England are much less enlightened. However, your right to roam in either country does not extend to the land around a private house or building.

So, although you might be able to determine the forage available in the Scottish countryside, you can’t be certain you would have good enough access to do the same in England. And in a city you could only map what forage was available by peering over fences from public roads.

So Elli Leadbetter and colleagues let the bees do the work.

They established 20 observation hives. Ten were in the the centre of London and 10 in agricultural land to the North East and South West of London. The hives were 5 km from each other to avoid overlapping areas of forage. They used observation hives so that they could watch and record the waggle dances of foragers in the hives.

I’ve discussed the waggle dance before. It is used to communicate three important pieces of information about a forage source:

- direction

- distance

- quality

The first two bits of information are encoded in the angle of the waggle run to the perpendicular and the duration of the waggle run. The quality is conveyed by the number of circuits a dancing working performs. It’s a case of ‘the more, the better’ … energetically higher quality resources {{10}} result in more circuits.

Having recorded thousands of these waggle dances, they used the direction and distance information to ‘map’ where the bees were foraging.

GIS data, land use and foraging bees

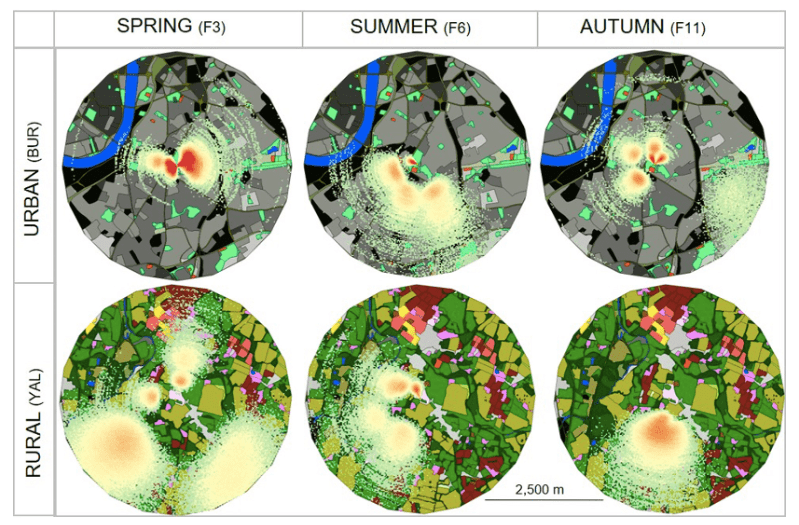

For many locations there exists a wealth of land use data (GIS data; Geographic Information Systems). Much of this is at high resolution. For each of the 20 observation hives they produced a map of land use within 2.5 km of the hive at a resolution of 25 m.

Land use was defined in broad categories such as {{11}} buildings, woodland, arable, pasture, fruit, OSR (all in agricultural areas) and dense or sparse residential, parks, amenity grassland or railways (all in urban landscapes).

They then used some clever mathematics to decode the waggle dances {{12}} to work out where the bees had been, converting the distance and direction components to geographic locations.

These locations were overlaid on the land use maps to produce ‘heat maps’ showing where the bees were foraging. The image above shows these heat maps. In the spring the urban bees (top left) were foraging intensively to the east and west of the hive and the rural bees (bottom left) were mainly foraging in two large areas to the south east and south west of the hive.

Foraging distance and nectar quality

Even a cursory look at the image above shows that the urban bees tended to forage closer to the hive than the rural bees. But remember, that’s just three snapshots during the season.

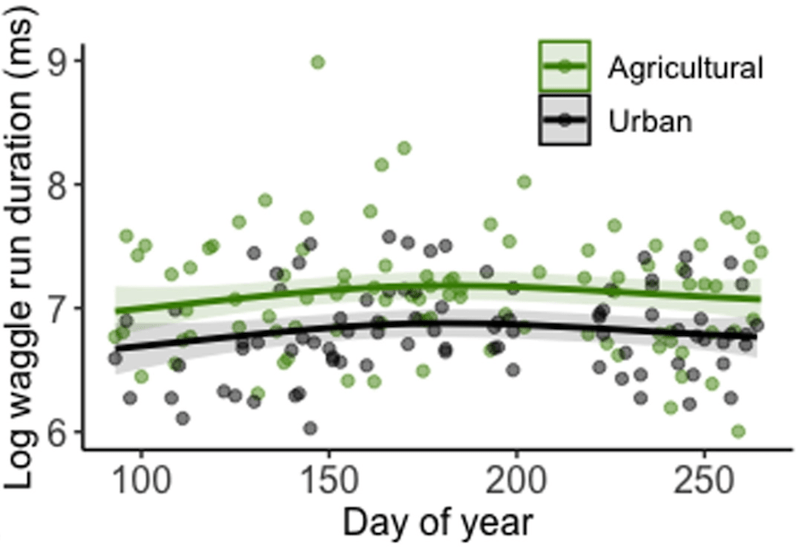

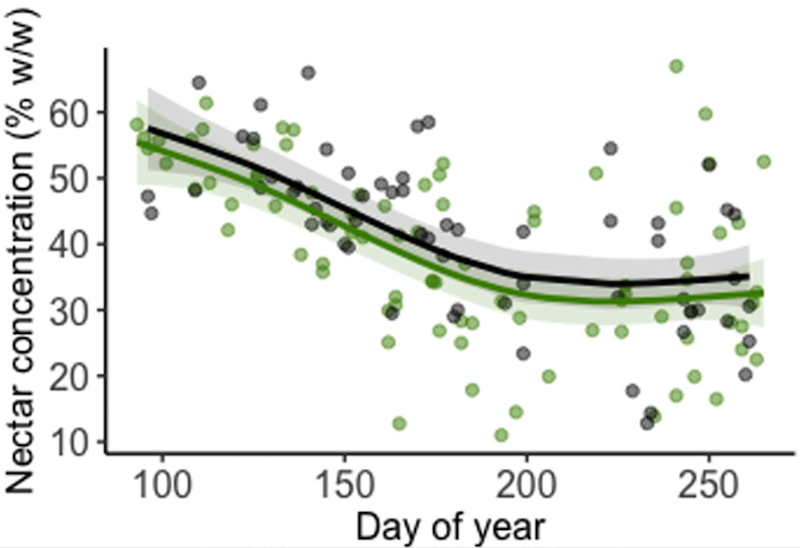

However, more detailed analysis confirmed that this was the case. Throughout the season, the bees in the agricultural landscape foraged further from the hive. I’m showing the log-transformed median waggle run duration (above) as this allows slightly easier comparison across the season. The further the wiggly ‘best fit’ line is above the horizontal axis, the longer the duration of the waggle dance run, and so the further the bees are flying to find the forage.

Interestingly, the median foraging distances were relatively short when compared with the maximum foraging distances from the decoded waggle dances. This applied wherever the bees lived. For urban bees the median was 492 m (max 9375 m) and for agricultural bees it was 743 m (max 8158 m {{13}} ).

Perhaps the agricultural bees were flying further because there was better quality nectar available at more distant sites?

They controlled for this by recovering returning foragers and robbing them of their nectar load before analysing the sugar content. There was no significant difference {{14}} between the nectar from agricultural or urban landscapes. The sugar content of the nectar was recorded as reducing through the season.

Foraging preferences

So where did the town bees and the country bees prefer to forage?

In urban areas the bees exhibited a strong preference for residential gardens (the ‘sparse residential land’) … these are presumably the flower-rich urban gardens that the homeowners also tend to prefer.

In contrast, bees in an agricultural landscape showed an entirely unsurprising reliance upon mass-flowering crops like oil seed rape (in spring only). They also showed weaker preferences for arable land and fruit crops throughout the season.

I’ve skipped over a host of additional observations from the study, and almost all of the controls. Two things that are worth mentioning though.

Firstly, hive strength had no influence on waggle dance duration (and hence foraging distance). It therefore wasn’t the case that stronger hives had a larger workforce that could survey and exploit more distant forage.

Secondly, cities are warmer due to the urban heat island effect. However, temperature also did not affect waggle dance duration when it was factored in. So, the city bees aren’t foraging at shorter distances because the dance is truncated at higher temperatures.

Conclusions

So, although cities are predominantly filled with buildings and roads, city bees travel less far to forage when compared to bees in agricultural landscapes.

This strongly suggests that the urban landscape consistently provided more available forage {{15}}.

Conversely, the bees in agricultural landscapes had to fly further, not because there were better quality nectar sources available at long-range, but because there wasn’t enough nectar nearby.

There were a number of additional interesting points in the paper, some of which were known already from other studies. For example, the high sugar content in spring nectar was already known (and confirmed here). Similarly, foraging distances in midsummer were longer than those in spring or autumn. This could be predicted due to the reduced rainfall in summer, and consequently the reduced overall level of nectar available.

I need to think more about how this study contributes – if at all – to the ‘too many bees in cities’ argument. If anything, forage-rich towns should be able to support a greater number of bees {{16}} without the honey bees impacting on other species. In contrast, honey bees in agricultural landscapes might dominate the available nectar sources because they can forage at long distances and then communicate to their nestmates the location.

Perhaps it just shows that that heavily farmed land is actually very poor in terms of nectar availability? It’s either boom or bust … once the OSR has finished, or the clover has been ploughed in, or the fruit trees stop flowering then there’s nothing left 🙁

It would be interesting to conduct a similar study in a forage-rich, non-agricultural, rural landscape.

Access all areas

Finally, I think a particularly neat thing about this study is the use of bees to ‘map’ the forage availability using what the authors term “a large-scale search effort that has no access limitations”. The scientists interpreted the waggle dance to get information that would otherwise have been difficult or impossible to determine.

However, using the bee’s own perception of the distances flown might actually lead to inaccuracies in the calculations. As discussed previously, bees measure distance by optic flow. Optic flow increases in complex landscapes … and cities are likely (at least to us, and certainly when compared with arable farmland, to bees) to be complex landscapes. Increased optic flow leads to a perception of increased distance, and hence to longer waggle runs.

This means that bees in complex landscapes might overestimate the distance they have actually flown to forage. Conversely, those in uniform landscapes might underestimate.

Which means that the results of this study may be a conservative estimate of the differences in foraging distance.

And therefore a conservative estimate of the differences in forage availability in urban and agricultural landscapes.

Notes

Dancing in the City was a pretty cheesy song that reached #3 in the charts for the rock-pop duo Marshall Hain in 1978. Having remembered the track when thinking up a title for this post, I made the mistake of listening to it on Spotify.

I now can’t get the damned thing out of my head.

But it gets worse. I rummaged through Wikipedia and discovered that Kit Hain, the vocalist, subsequently had a very successful songwriting career with people like Roger Daltrey, Chaka Khan and Fleetwood Mac. Impressive.

In contrast, Julian Marshall, the keyboard player became a member of the Flying Lizards who had a minor hit with a cover version of Barrett Strong’s {{17}} Money (That’s What I Want) …

… and now I can’t get that out of my head 🙁

{{1}}: From an upstairs window, if you stood on tiptoe … with binoculars.

{{2}}: Which was, without fail, successful every year.

{{3}}: Based on the unedifying small patch of turf in my garden.

{{4}}: Don’t they know we all use garishly coloured polystyrene hives these days?

{{5}}: MacIvor JS, Packer L (2015) ‘Bee Hotels’ as Tools for Native Pollinator Conservation: A Premature Verdict?. PLOS ONE 10(3): e0122126. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0122126

{{6}}: If I remember …

{{7}}: Never much good for nesting birds or foraging bees.

{{8}}: Or at least most, with the exception of mine.

{{9}}: Samuelson, A. E., Schürch, R., & Leadbeater, E. (2021). Dancing bees evaluate central urban forage resources as superior to agricultural land. Journal of Applied Ecology, 00, 1– 10. https://doi.org/10.1111/1365-2664.14011

{{10}}: Taking account of the energy invested in travel and the energy gained in food intake.

{{11}}: These are incomplete lists just to give you a flavour of the types of land use they defined.

{{12}}: 2800 of them in total, recorded fortnightly between April and September.

{{13}}: These maxima are extrapolated, not actual distances … it seems unlikely a forager would fly a total of almost 19 km.

{{14}}: The ‘best fit’ lines and their errors are almost superimposed in the graph above.

{{15}}: I told you I was wrong (yet again) in the opening paragraphs.

{{16}}: Whether honey bees, bumble bees or solitary bees.

{{17}}: Of Tamla Motown fame.

Join the discussion ...