Fondant, mushrooms and DWV

Synopsis: Two recent studies on potential therapies for DWV and a discussion of the practicalities of feeding fondant … and recovering the leftovers.

Introduction

This is the 47th post of 2023 and I’ll soon be writing the pre-Christmas seasonal reviews, the recommended list of presents for beekeepers and the annual “If you’ve not yet treated with oxalic acid then you’ve left it too late” reprimand. But there’s still a week or so until the last of those is needed, so I’ll discuss something else today

It’s always a little tricky to know what to write about at this stage of the season. Some hardcore science will leave those searching for timely practical beekeeping tips wanting. Conversely, those of you who have already done your winter oxalic acid treatment {{1}} on your broodless colonies don’t need any practical tips as you’re now free to think about other things until early March.

So, in the hope of pleasing ‘all of the people some of the time’ {{2}}, I’m going to mix’n’match some very recent science with a couple of comments about late season colony management. And, if that wasn’t enough, I’ve thrown in a very brief paragraph at the end of some future changes that will be happening here.

Feeding fondant

I only feed fondant when preparing colonies for winter. Most of my colonies this season received either 6 kg (because the brood box was heavily backfilled with stores already) or a full 12.5 kg block. They’re unlikely to need more before Spring, and some didn’t even manage to finish the block I did give them (more on that later).

Fondant is undoubtedly more expensive than feeding syrup. I’ve never worked out how much more expensive because I don’t really care … the benefits to me far outweigh the cost differential.

- I’ve no need to purchase and store syrup feeders, be they 15 kg buckets with perforated lids, washing up bowls filled with straw, or a £72 Ashforth feeder. Yikes!

- I don’t need to stand over the stove mixing gallons of thick (2:1 by weight) syrup, or keep barrels to carry and distribute it … which also means I don’t spill it in the apiary and encourage robbing (or, worse, the kitchen and all the grief that would entail).

- Fondant is ready-wrapped, stable and can be stored for years. It’s always ready to use. I’ve got a couple of hundred kilograms tucked away ‘just in case’ in the shed.

- Colonies take fondant down more slowly. I think this helps the queen lay eggs for longer as the brood nest isn’t backfilled with syrup being ripened. Other than seemingly common sense, I’ve got no real proof for this and should perhaps formally test the theory {{3}}.

- The empty boxes can accommodate sixteen 340 g jars and are useful for distributing honey in.

- There’s more, but that’s enough to be going on with.

Leftovers

Most colonies finish their fondant, though this depends upon the availability of late season nectar. Bees continue to forage and at some point they run out of space, so some fondant may remain.

My east coast bees tend to finish everything, just leaving an empty ‘husk’ – the blue bag – stuck down to the queen excluder with a bit of propolis and brace comb. On the west coast the bees are very frugal, it’s a bit warmer and they often don’t even finish a half block of fondant. The brood box is often heavy with late-season heather stores.

Hold on … queen excluder?

If you need access to the brood box – for example, to add, reposition or remove Apivar strips – it’s very difficult if there’s a big block of fondant stuck down onto the top bars of the frames. Instead, it’s far easier to use a framed wired queen excluder (QE) to support the fondant just above the top bars. The QE can easily be lifted, together with the fondant, and just as easily replaced … without crushing a generation of bees.

However, as the colder weather approaches I like to remove any remaining fondant before the bees cluster tightly for the winter.

Why remove it?

I was asked this recently after talking to the good folks at Perth and District BKA. There are three reasons:

- The hives are full of stores. My bees are frugal. It’s unlikely they’ll finish their stores. In fact, it’s not unusual for me to remove a frame of sealed stores from the outside of the box in early spring (which I put aside for making up nucs in June) to give the colony space to expand. Since they probably don’t need the fondant there seems little point in leaving it – and a couple of reasons (see below) not to.

- Fondant under the crownboard will act as a heatsink and absorb some of the warmth generated by the colony. Of course, if the roof is sufficiently well insulated this shouldn’t be an issue, but the fondant, the space around it and any additional gaps created by the eke used to accommodate it would all be better if they weren’t there.

- More significantly, fondant deliquesces {{4}}. Unless the bees are constantly nibbling away at the lower face of the block it may get sufficiently gloopy to drip down between the brood frames. The only time this is an issue is if the colony is small (or gets small during the winter) and/or the cluster moves away from the fondant overhead. Again, better avoided in the first place.

I heft the colonies periodically in the winter so, if they are too light, I can add fondant back as needed.

Removing the fondant

It’s mid/late November, 7°C and spitting with rain.

The quickest way to recover the excess fondant is to remove the roof and crownboard, prise up the QE and fondant block, shake off the bees (then shake off yet more bees) and then reassemble the hive.

However, even then there may be more bees lethargically wandering around the sticky face of the fondant block, rapidly getting chilled. Do you sacrifice these or leave the block out hoping that the bees will fly back … which, at 7°C is probably the same thing.

It’s easier – though takes two visits – to remove the roof then gently prise up the QE, fondant and crownboard before immediately returning them to the hive over a clearer board. The bees make their own way back to the cluster, benefitting from the warmth of the colony. The following day remove the clearer, QE and fondant and replace the crownboard and roof.

I did this on half a dozen hives last week; barely a bee flew on either visit and the underside of the fondant was completely clear of bees after removal. The colony was almost undisturbed and there were no casualties.

I store the recovered unused fondant in a tightly sealed plastic bag. Don’t leave it uncovered as it will absorb water. If needed later in the winter I’ll either use it ‘as is’, or add 1-2 kg blocks to plastic trays (typically from supermarket packaging of meat or mushrooms) for underweight colonies. Alternatively, I dissolve it in hot water (60% by weight) to make thin syrup for stimulative early season feeding.

Magic mushrooms

And, since I’ve mentioned mushrooms …

An interesting paper has recently been published in The Journal of Insect Physiology on mushroom (Cortinarius caperatus) extracts and DWV infection (Svobodová et al., 2023). The introduction ends with the following sentence:

Our results demonstrated that the alcohol extract of C. caperatus can be used as a safe and effective treatment to reduce DWV infection.

Hmmm … perhaps.

Mushroom extracts (and, more specifically, their secondary metabolites) have long been known to have antiviral effects. Some stop viruses infecting cells while others prevent the viruses from replicating once they have infected cells (two different things altogether, though not all studies appear to understand this). Usually the mechanism of action remains a mystery.

Svobodová and colleagues show that an alcohol extract – or simply a powdered preparation – of the edible gypsy mushroom Cortinarius caperatus appeared to inhibit the levels of deformed wing virus (DWV) in caged honey bees.

Nice.

Hold on … the title of the paper states ‘inhibits the development [of] infection’ of DWV. The bees are already infected and there’s no evidence that the mushroom extract stops them getting infected. Bees fed mushrooms have lower amounts of virus, so perhaps it inhibits the replication of the virus that’s already present?

Pedantry perhaps … that’s my prerogative.

How great is the inhibition?

Apparently pretty good.

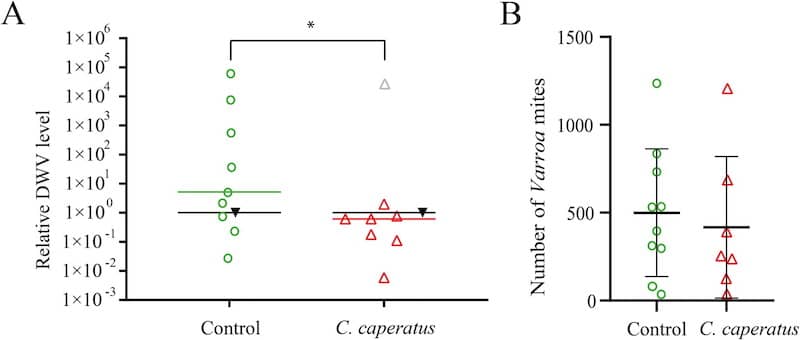

Bees fed mushroom extracts have virus levels that are about 1/1000th of the control bees.

But …

You knew there had to be a but.

The absolute levels of virus are not shown in the paper. Let’s provide some context. A bee exposed to Varroa during development might contain up to 1012 copies of the virus. That’s 1,000,000,000,000 or a trillion. Some mite-parasitised bees have lower virus levels, perhaps 100-1,000 times less, but it’s still a very large number of viruses.

Bees not exposed to Varroa during development (in a hive in which mite levels are well controlled) may contain only 104 or 105 copies of the virus. A biggish number (10,000 to 100,000), but ten million times smaller than a trillion.

Therefore, meaningful reductions of virus levels are measured in millions, not thousands. At least meaningful in terms of bee or colony health.

How do colonies (rather than caged bees) respond when fed extracts of mushrooms?

Not particularly convincingly. The graph in the paper (A, above) shows a 10-fold reduction in relative virus levels which is statistically significant, but not exactly overwhelming. Interestingly, one outlier sample (the grey triangle) was omitted from the calculations for some reason and I suspect this data would not have been statistically significant had it been included.

There’s more in the paper (no mushroom residues in honey, no apparent detrimental impact on worker bee longevity, gene expression studies etc.) and it’s certainly a topic that deserves more work.

But, it’s a very long way from being a ‘safe and effective treatment to reduce DWV infection.’

So, magic mushrooms … but not magic bullets.

Mushroom extracts (something I’ve written about previously) are probably not (yet?) a quick-fix to the Varroa-DWV problem.

dsRNA

And, as another recent paper (Smeele et al., 2023) suggests, nor is double stranded RNA (dsRNA).

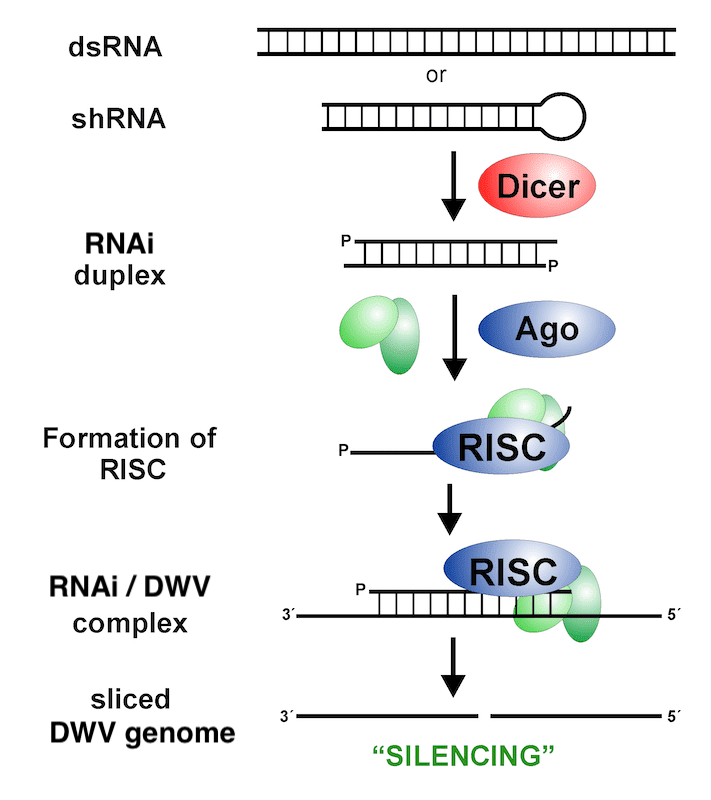

Like the mushrooms, I’ve discussed dsRNA a couple of times before. It is a way to induce an RNAi (interfering RNA) response. You should think of this as the immune system of bees (or, more generally, insects); like our own immune system it ‘learns’ from pathogen exposure, and it can be ‘primed’ by prior vaccination to provide subsequent protection. Unlike our immune system it is based upon nucleic acids, rather than proteins.

I’m not going to go into the gory details of this paper as the results are negative i.e. what they attempted to do (vaccinate bees against DWV) did not work. This was both disappointing and a little surprising as previous studies have shown a reduction in DWV levels by prior feeding of bees with syrup contains dsRNA that targets DWV.

However, this study was done a little differently, and in a manner that much more closely recapitulates how developing pupae are exposed to DWV. As such it is particularly interesting, and suggests that dsRNA ‘therapies’ may not offer as much promise as initially thought.

Experimental mini-nucs were maintained, fed with syrup containing dsRNA against DWV (or control dsRNA) and Varroa were added. Developing larvae were fed by workers, the cells were capped (with or without prior Varroa infestation) and the workers that subsequently emerged were examined for deformed wings, virus levels and evidence of Varroa parasitisation.

Although Varroa parasitised bees had very much higher virus levels, prior feeding with DWV-specific dsRNA did not reduce the proportion of bees with wing deformities or the levels of DWV in these bees.

Why the difference with previous studies?

In this experiment the acquisition of DWV was via two routes; while being fed by the nurse bees in the mini-nucs, and – for the unfortunates exposed to mites – while being fed on by the parasitising Varroa within the capped cell.

It is the inclusion of the latter transmission route that really sets this study apart, and what makes it a more realistic test to determine whether a potential therapy is effective.

The hope/expectation was that the developing pupae would have acquired dsRNA from the nurse bees, an antiviral immune response would have been stimulated in the pupae and they would have therefore had lower DWV levels (and fewer symptoms) after exposure to Varroa.

Smeele and colleagues explain their failure to demonstrate this by differences in the nucleic acid sequence of the dsRNA and the viruses acquired from Varroa.

Effectively the vaccine and the virus were imperfectly ‘matched’.

Whilst certainly a possibility there may be an alternative explanation to do with the localisation of the immune response which wasn’t discussed. Perhaps Varroa-acquired DWV bypasses this immune response when the mite feeds upon the haemolymph or fat body of the developing pupa?

DWV is a variable virus. During replication it makes errors which are incorporated into the virus genome. Some are detrimental (these are lost because the virus is uncompetitive or non-viable), others are beneficial and selected for. The remainder are neutral … but these still mean that the virus varies and so may contribute to escape from the immune response (whether natural or induced by dsRNA).

Any effective DWV therapy must take into account this natural variation in the DWV population, and the results presented by Smeele et al., (2023) suggest that this may be far from straightforward.

The future of The Apiarist

The Apiarist is ten years old next month. The site ‘design’ (and I use that term in the loosest possible sense) is getting unwieldy, difficult to read and – increasingly – very time consuming to maintain. Early next year there will be a major overhaul of things. Some ‘features’ will disappear altogether, hopefully together with some of the flaws.

Inevitably some things will get broken … it’ll get worse before it gets better.

I’ll provide some additional information before I press CTRL-ALT-DEL.

References

Smeele, Z.E., Baty, J.W., and Lester, P.J. (2023) Effects of Deformed Wing Virus-Targeting dsRNA on Viral Loads in Bees Parasitised and Non-Parasitised by Varroa destructor. Viruses 15: 2259 https://www.mdpi.com/1999-4915/15/11/2259.

Svobodová, K., Krištůfek, V., Kubásek, J., and Bruce Krejčí, A. (2023) Alcohol extract of the gypsy mushroom Cortinarius caperatus inhibits the development of Deformed wing virus infection in western honey bee (Apis mellifera). Journal of Insect Physiology 104583 https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0022191023001099.

{{1}}: Award yourself a gold star and a pat on the back.

{{2}}: Which, according to John Lydgate, is about all I can hope for.

{{3}}: Not actually easy to do.

{{4}}: From the Latin dēliquēscere, to melt away, dissolve.

Join the discussion ...