Honeyguides

That’s not a typo.

I didn’t mean Honey Guides … or honey guide.

Honeyguides are a group of 17 species of birds, distributed into four genera, belonging to the family Indicatoridae. All of the 8 species that have been well studied are brood parasites, like the cuckoo (Cuculus canorus). They lay their eggs in the nest of another species – usually a specific species as they are evolutionarily adapted to match the egg size and shape {{1}} – and subsequently puncture the other eggs to destroy the developing embryo.

There’s some great research on the evolutionary arms race between the egg puncturing ability of honeyguides and the eggshell thickness of the host species {{2}} … but I’ll leave that as your homework for the holidays {{3}} as I want to discuss something else about honeyguides.

Indicatoridae by name, indicator by nature

The really remarkable thing about honeyguides is hinted at by the family name.

Indicatoridae

This reflects their ability to lead human honey hunters to a wild honey bee nest site.

Of the 17 species of honeyguides, it is only the greater honeyguide (Indicator indicator) that has been extensively studied for its guiding behaviour. There is disagreement whether the scaly-throated honeyguide also exhibits similar guiding activity.

For the rest of this post, when I say ‘honeyguide’ I mean the greater honeyguide.

The greater honeyguide lives in dry open woodland in sub-Saharan Africa. It is a rather dull-coloured, starling-sized bird. It eats honey bee larvae, pupae and wax from the nest, and is one of the few birds that can digest wax.

However, the honeyguide cannot access most wild honey bee nest sites. These are often in a hollow tree and are well-defended by the bees.

But, over millenia, the honeyguide has learned that honey hunters, who have the benefit of being able to use smoke to calm the bees {{4}}, leave a lot of debris after robbing the nest of honey.

And, over millenia, the honeyguide and honey hunters have evolved a mutualistic relationship in which the bird guides the human to the bee’s nest. The hunter gets the honey (and probably pupae, an important source of protein) and the honeyguide gets the leftovers.

“Mutualism describes the ecological interaction between two or more species where each species has a net benefit.”

Everybody wins 🙂

Guiding behaviour

Greater honeyguides are territorial and scout out the location of wild bee nests in their territory. Each territory may contain multiple honey bee nests.

To attract the attention of a honey hunter the honeyguide emits a distinctive chattering call {{5}}.

They then flit from tree to tree, towards the honey bee nest, perching and spreading the tail to expose two conspicuous white spots.

This behaviour was reported as long ago as 1588. João dos Santos, a Portuguese missionary, described the ability of the bird to lead honey hunters to bees’ nests (and also described how the bird would enter the church to eat the wax candles).

Guiding by honeyguides is very effective.

The honey hunters have learned to recognise the distinctive call, flight and perching activity of the bird {{6}}. Studies have shown that ~75% of guiding events lead to the successful identification of at least one nest. 95% of these were honey bees nests and the remainder were stingless bees.

Smoke ’em out

Once the nest has been located the honey hunter uses smoke to calm the bees. Often the nests are located high up in the tree so the hunters attach some smouldering wood to a long pole and hold it near the nest entrance. They can then climb the tree and approach safely.

There are no bee suits or veils used … many of the photographs of honey hunters I’ve seen show them wearing just sandals and shorts.

The entrance is widened with a machete and the honey-laden combs are extracted intact and lowered to the ground … no doubt after a little ‘quality control’.

It’s not just humans who value honey … chimpanzees love the stuff as well, but they eat less than 1% of the honey consumed by humans in the same area. Chimpanzees, although known to use tools, do not know how to exploit fire. They are therefore ineffective honey hunters.

In a multi-year study of chimps in the Kibale National Park, Uganda, about 60% of of bees’ nests were successfully defended by the bees, driving the chimps away by stinging them. In contrast, human honey hunters are never driven away after smoking the nest.

Smoke is the key component needed for successful robbing of the nest by the honey hunters.

Two way communication

So, the honeyguide signals – with calls and its characteristic behaviour – to the honey hunter, guiding them to the nest site. The honey hunter can ‘read’ and understand these signals and can accurately home in on the nest.

But what if you are a honey hunter and, as you start your foraging, there are no honeyguides to be seen or heard?

This is where the close relationship between the honeyguide and the honey hunter becomes even more extraordinary.

The honey hunter calls to attract the honeyguide.

Not just any call, but a specific call … and to add an additional level of complexity, different tribes use different specific calls to attract honeyguides.

Remember, these are wild birds.

We’re all used to communicating with domesticated animals … “Here Fido!” {{7}}, but a specific call to attract a wild animal is probably unique.

The Yao honey hunters in Mozambique use a distinct ‘brrrr-hm’ call to summon the honeyguide.

An excellent study by Claire Spottiswoode and colleagues showed that this call, not used by the Yao people for anything else, more than doubled the likelihood of attracting a honeyguide to the honey hunter and initiating guiding by the honeyguide {{8}}. The call successfully attracted a honeyguide about two-thirds of the time it was used.

The characteristic ‘brrrr-hm’ call is passed down the generations of Yao honey hunters – from father to son {{9}} – meaning that a bird hearing the call could be reasonably certain the caller has the skills and tools necessary to harvest the honey.

Learning the lingo

Not all honey hunters use the same call. The Hadza people of northern Tanzania use a melodious whistle to attract honeyguides. The Kenyan Boran people use a distinctive sharp whistling call.

Different geographic populations of honeyguides clearly recognise distinct calls by the hunters.

How do the birds learn to recognise the call of the honey hunter?

Obviously not from their biological parents.

Remember, these are brood parasites and they are reared by other species such as lesser bee eaters or green woodhoopoes.

And there’s another amazing story here as these hosts have different shaped eggs {{10}}. Different lineages of honeyguide have evolved that lay a suitably shaped egg that matches that of the specific host {{11}}. The host specialisation is thought to reside on the female-specific W chromosome.

OK … enough digression.

It appears that honeyguides have an innate ability to recognise human calls. As young birds they listen for these calls and learn them, a process presumably reinforced through successful honey hunting in concert with humans.

Whether juvenile Tanzanian honeyguides transported to Kenya or Mozambique could identify the ‘local’ honey hunter’s call has not been tested, but would be interesting. I wouldn’t be surprised if the call used by the honey hunter has not also evolved (the evolution of languages is itself a fascinating area) to be distinctive from other sounds in the particular area, or to carry longer distances … or that is more attractive to the honeyguides.

The evolution of mutualism between humans and honeyguides

How did humans learn to call and follow honeyguides?

Originally it was thought to involve copying the natural guiding by the bird of honey badgers (ratels).

However, this story has largely been discredited – ratels do not call to attract the honeyguide and there’s a suspicion that videos showing birds guiding badgers have been staged {{12}}.

Instead, it is much more likely that the mutualistic relationship between humans and honeyguides evolved over a very long period.

Since we’re talking about evolutionary timeframes here this could potentially mean millions of years.

Have humans been about that long?

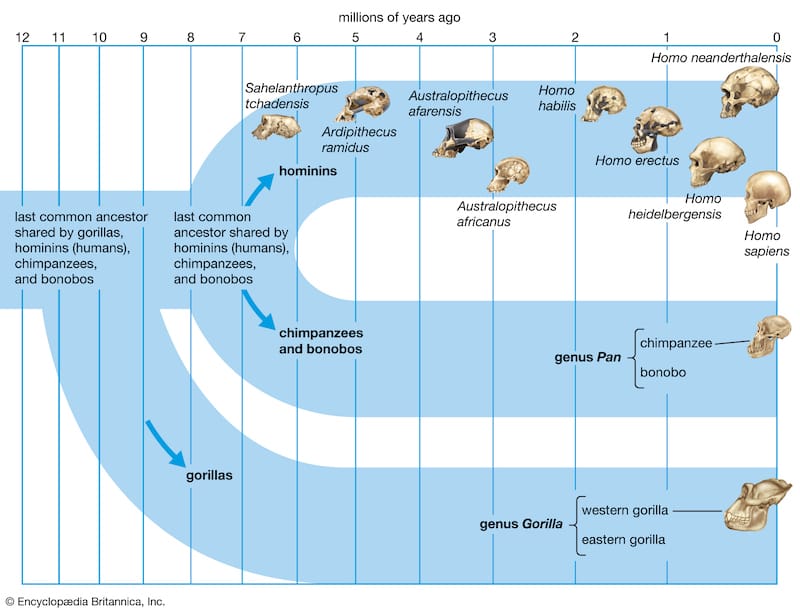

No … we are the ‘new kids on the block’. Homo sapiens evolved from our hominin ancestors about 300,000 years ago. Therefore it’s likely that early hominins such as the (relatively recent) H. heidelbergenesis (0.4 million years ago (Mya) ), H. erectus (1.6 Mya) or H. habilis (2 Mya) were involved instead.

Have honeyguides been about that long?

Yes … analysis of the mitochondrial DNA (inherited solely from the mother) of those distinct burrow- or tree-nesting lineages of honeyguides demonstrated that they diverged at least 3 million years ago.

Have honey bees been around that long?

Certainly … Apis mellifera probably evolved from other cavity-nesting bees about 6 Mya {{13}}

There’s no smoke without fire

One of the great debates about the evolution of humans is when our ancestors learnt to create and use fire.

There is good evidence for use of fire about 1 Mya and additional claims that evidence control of fire 1.7 – 2 Mya {{14}}.

All of which provides ample time for the evolution of mutualistic behaviour between H. erectus and the greater honeyguide.

This behaviour cannot have evolved without the ability of early hominins to control fire. The study of chimpanzees failing to successfully and efficiently collect honey shows this must be the case.

At least 44 distinct African ethnic groups exhibit the type of mutualistic relationship with honeyguides I have described and current studies are aimed at determining when the hominin-honeyguide mutualism evolved {{15}}.

The fossil record cannot help us here. There’s also a huge gap between the evolution of the early homonins and the upper Paleolithic rock art that clearly depicts honey hunters smoking bees’ nests.

More studies are needed. However the inexorable passage of time is now accompanied by increasing urbanisation, the availability of refined sugar and exclusion of hunter gatherers from nature reserves. This means that people depend less on honeyguides.

In time I expect it will be inevitable that this wonderful example of interspecies cooperation will be lost.

As another year draws to a close and you spread honey on your breakfast toast, take a moment to marvel at how our ancestors’ love of honey resulted in the evolution of the only known mutually beneficial relationship between a wild bird and humans.

Extraordinary.

Happy Christmas

Notes

There’s a BBC Natural Histories podcast on honeyguides featuring Claire Spottiswoode available online. The programme notes are:

The greater honeyguide is unique: it is the only wild animal that has been proven to selectively interpret human language. Brett Westwood tells the sweet story of a bird that leads human honey hunters to wild bees’ nests in order to share the rewards – perhaps one of the oldest cultural partnerships between humans and other animals on Earth. With biologist Claire Spottiswoode, anthropologist Brian Wood, and honey hunters, Lazaro Hamusikili in Zambia and Orlando Yassene in Mozambique, and the calls of the honeyguide. Producer: Tim Dee.

{{1}}: Though not colour … as they parasitise burrow or tree hole-nesting birds and it’s too dark to discern colour.

{{2}}: Spottiswoode, C.N. & Colebrook-Robjent, J.F.R. (2007) Egg puncturing by the brood parasitic Greater Honeyguide and potential host counteradaptations. Behavioral Ecology 18: 792-799.

{{3}}: And, while you’re at it … if you’re interested in cuckoos, I can thoroughly recommend Cuckoo: Cheating by Nature written by Nick Davies.

{{4}}: I’ll return to smoke shortly … as there’s no smoke without fire.

{{5}}: Female honeyguide chattering call © Étienne Leroy licensed CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 and available on dlbird.com.

{{6}}: Isack & Reyer (1989) Honeyguides and honey gatherers: interspecific communication in a symbiotic relationship. Science 243:1343-6.

{{7}}: Does anyone call their dog Fido? Yes, they do. Abraham Lincoln did for example. Fido is derived from the Latin meaning ‘to trust, believe, confide in’ i.e. faithful.

{{8}}: Spottiswoode et al., (2016) Reciprocal signaling in honeyguide-human mutualism. Science 353:387-9.

{{9}}: Honey hunters appear to all be male in the reports I have read.

{{10}}: This might feel like I’m moving off-topic, but – as you will see – the evolution of egg shape turns out to be important.

{{11}}: Spottiswoode, C.N. et al., (2011) Ancient host-specificity within a single species of brood parasitic bird. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the USA 108: 17738-17742.

{{12}}: Dean, W. R. J. et al., (1990). “The Fallacy, Fact, and Fate of Guiding Behavior in the Greater Honeyguide”. Conservation Biology. 4: 99–101.

{{13}}: Cornuet JM, Garnery L. (1991) Mitochondrial-DNA variability in honeybees and its phylogeographic implications. Apidologie 22:627–642.

{{14}}: For comparison, stone tools and bipedalism date back to a little under 3.5 Mya and 4 Mya respectively.

{{15}}: See Hromada et al., (2017) A taste for honey: on the co-evolution of pyrophilic primate, honeyguides, and honeybees.

Join the discussion ...