Leave and let die

If you follow some of the online discussions on Varroa you’ll see numerous examples of amateur beekeepers choosing not to treat so as to ‘select for mite-resistant bees’.

For starters it’s worth looking at the ‘treatment-free’ forums on Beesource.

The principle is straightforward. It goes something like this:

- Varroa is a relatively new {{1}} pathogen of honey bees who therefore naturally have no resistance to it (or the viruses it transmits).

- Miticide treatment kills mites, so favouring the survival of bees.

- Consequently, traits that confer partial or complete resistance to Varroa are not actively selected for (which would otherwise happen if an untreated colony died out).

- Treatment is therefore detrimental, at the population level if not the individual level, to the development of Varroa-resistant bees.

- Therefore, don’t treat and – with a bit of luck – a resistant strain of bees will appear.

A crude oversimplification?

Yes, I don’t deny it.

There are all sorts of subtleties here. These range from the open mating of queens, isolation of apiaries, desirable traits (with regards to both disease resistance and honey production {{2}}), livestock management ethics, our responsibilities to other beekeepers and other pollinators. I could go on.

But won’t.

Instead I’ll discuss a short paper published in the Journal of Apicultural Research. It’s not particularly novel and the results are very much in the “No sh*t Sherlock” category. However, it neatly emphasises the futility of the ‘do nothing and expect evolution to find a solution’ approach.

But I’ll start with a simple question …

How many colonies have you got?

One? (in which case, get another)

Two?

Ten?

One hundred?

Eight-two thousand? {{3}}

Numbers matters because evolution is a numbers game. The evolutionary processes that result in alteration of genes (the genotype of an organism) that confer different traits or characteristics (the phenotype of an organism) are rare.

For example, viruses are some of the fastest evolving organisms and, during their replication, mutations (errors) occur at a rate of about 1 in 104 at the genetic level {{4}}.

But so-called higher organisms (like humans or bees) have much more efficient replication machinery and make very many fewer errors. A conservative figure for bees might be about 10,000 times less than in these viruses (i.e. 1 in 108), though it could be as much as a million times less error-prone {{5}}

There are lots of other evolutionary mechanisms in addition to mutation but the principle remains broadly the same. The chance changes that are acquired by copying or mixing up genetic material are very, very infrequent.

If they weren’t, most replication would result – literally – in a dead end.

OK, OK, enough numbers … what about my two colonies?

So, since the evolutionary mechanisms make small, infrequent changes, the chance of a beneficial change occurring is very small. If you start with small numbers of colonies and expect success you’re likely to be disappointed.

Where ‘likely to be’ means will be.

The chances of picking the Lotto jackpot is about 1 in 45 million for each ticket purchased. If you expect to win you will be disappointed.

If you buy two tickets (with different numbers!) your chances are doubled. But realistically, they’re still not great {{6}}.

And so on.

Likewise, the more colonies you have, the more likely you’ll get one that might – by chance – acquire a beneficial mutation that confers some level of resistance to Varroa.

Of course, we don’t really know much about the genetic basis for resistance (or tolerance?) to Varroa in honey bees. We know that there are behavioural changes that increase survival. We also know that Apis cerana can cope with Varroa because it has a shorter duration replication cycle and exhibits social apoptosis.

There are certainly ‘hygienic’ and other traits in bees that may be beneficial, but at a genetic level I don’t think we know the number of genes that are altered to confer these, or how much each might contribute.

So we don’t know how many mutations will be needed … One? One hundred? One thousand?

If the benefit of an individual mutation is very subtle it might offer relatively little selective advantage, which brings us back to the numbers again.

Apologies. Let’s not go there.

Let’s cut to the chase …

Comparison of treated vs untreated colonies over 3 years

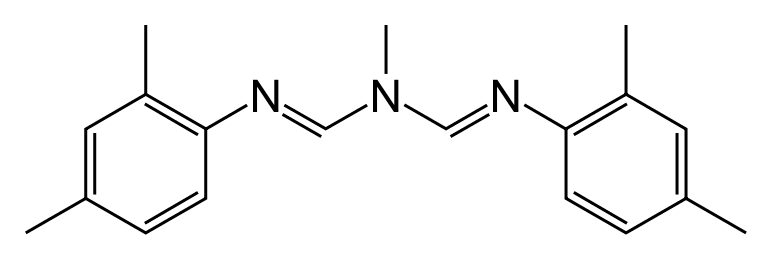

Miticides – whether hard chemicals like Amitraz or Apistan or organic acids like formic or oxalic acid – work by exhibiting differential toxicity to mites than to their host, the bee. They are not so specific that they only kill mites. They can harm other things as well … e.g. if you ingest enough oxalic acid (5 – 15g) it can kill you.

Jerzy Wilde and colleagues published their study {{7}} comparing colonies treated or untreated over a three year period. The underlying question addressed in the paper is “What’s more damaging, treating with potentially toxic miticides or not treating at all?”

The study was straightforward. They started with 100 colonies, requeened them and divided them randomly into 4 groups of 25 colonies each. Three received treatment and one was a control.

The ‘condition’ of the colonies was measured in a variety of ways, including:

- Colony size in Spring (number of combs occupied)

- Nosema levels (quantified by numbers of spores)

- Mite drop over the winter (dead mites per 100g of ‘hive debris’)

- Colony size in autumn (post-treatment) and egg laying rate by the queen

- Winter losses

The last one needs some explanation because in one group (guess which?) there were more winter losses than they started the experiment with.

Overwintering colony losses were made up from splits of colonies in the same group the following year, so that each year 25 colonies went into the winter i.e. surviving colonies were used to generate additional colonies for the same treatment group.

Treatment and seasonal variation

To add a little complexity to the study the authors compared three treatment regimes:

- Hard chemicals only – active ingredients amitraz or the pyrethroid flumethrin (the research group are Polish, so the particular formulations are those licensed in Poland – Apiwarol, Bayvarol and Biowar).

- Integrated Pest Management (IPM) – a range of treatments including Api Life Var (primarily a thymol-based treatment) in spring, drone brood removal early/mid season, hard chemical or formic acid in late summer/autumn and oxalic acid in midwinter.

- Organic (natural) treatments only – Api Life Var in spring, the same or formic acid in late summer and a midwinter oxalic acid treatment.

The fourth group were the untreated controls.

To avoid season-specific variation they conducted the experiment over three complete seasons (2010-2012).

The results of the study are shown in a series of rather dense tables with standard deviation and statistic significance … so I’ll give a narrative account of the important ones.

Results …

The strength of surviving colonies in Spring was unaffected by prior treatment (or absence of treatment) but varied significantly between seasons. In contrast, late summer colony strength was significantly worse in the untreated control colonies. In addition, the number of post-treatment eggs laid by the queen was significantly lower (by ~30%) in untreated control colonies {{8}}.

Remember that early autumn treatment is needed to reduce Varroa infestation and so protect the winter bees that are being reared at this time from the mite-transmitted viruses.

The most dramatic effects were seen in winter losses and (unsurprisingly) mite counts.

Mites were counted in the hive debris falling through the open mesh floor during the winter. In the first year the treated and untreated controls had similar numbers of mites per 100g of debris (~12). In all treated colonies this remained about the same in each subsequent season. Conversely, untreated controls showed mite drop increasing to ~43 in the second year and ~114 in the final year of the study.

During the three years of the study 30 untreated colonies died. In contrast, a total of 37 colonies from the three treatment groups died.

The summary sentence of the abstract to the paper neatly sums up these results:

Failing to apply varroa treatment results in the gradual and systematic decrease in the number of combs inhabited by bees and condition of bee colonies and consequently, in their death.

… and some additional observations

Other than oxalic acid, none of the treatments used significantly affected the late season egg laying by the queen. Api Life Var contains thymol and many beekeepers are aware that the thymol in Apiguard quite often stops the queen from laying. Interesting …

I commented last week on queen losses with MAQS. In this Polish study, 8 of 50 colonies treated with formic acid suffered queen losses.

In the third season (2012) 45% of the 100 colonies died. More than half of these lost colonies were in the untreated controls. In contrast, overall colony losses in the first two years were only 9% and 13%. Survival of untreated colonies for a year or two is expected, but once the Varroa levels increase significantly the colony is doomed.

Overall, colonies receiving integrated pest management or hard chemical treatment survived best.

Evolution …

Remind yourself where the colonies came from that were used to make up the losses in the treatment (or control) groups … they were splits from colonies within the same group. So, colonies that survived without treatment were used to produce more colonies to not be treated the following season.

Does this start to sound familiar?

Jerzy Wilde and colleagues started with 25 colonies in the untreated group. They lost 30 colonies over a 3 year period and ended up with just two colonies. Had they wanted to continue the study they would have been unable to recover their losses from these two remaining colonies.

If you don’t treat you must expect to lose colonies.

Lots of colonies.

Actually, almost all of them.

… takes time

This study lasted only three years. That’s not very long in evolutionary terms (unless you are a bacterium with a 20 minute replication cycle).

It would be unrealistic to expect Varroa resistance to almost spontaneously appear. After all, there are about 91 million colonies worldwide, the majority of which are in countries with Varroa. Lots of these colonies will not be treated. If it was that easy it would have happened many times already.

What happens when you start with more colonies and allow more time to elapse?

Well, this ‘experiment’ has been done. There are a number of regions that have well-documented populations of feral honey bees that are living with, if not actually resistant to, Varroa.

One well known population are the bees in the Arnot Forest studied by Thomas Seeley. These bees have behavioural adaptations – small, swarmy colonies – that lessen the impact of Varroa on the colony {{9}}.

Finally, returning to the title of this post, there is the so-called “Bond experiment” conducted on the island of Gotland in the Baltic Sea. Scientists established 150 colonies of mite-infested bees and let them get on with it with no intervention at all. Over the subsequent six years they followed the co-evolution of the mite and the bee {{10}}.

It’s called the “Bond experiment” or the Live and Let Die study for very obvious reasons.

Almost all the colonies died.

Which is why the title of this post is more appropriate for those of us with only small numbers of colonies.

{{1}}: In evolutionary terms one hundred years is the blink of an eye …

{{2}}: Or whatever else floats your boat … pollination services, wax, royal jelly or propolis production etc.

{{3}}: Adee Honey Farms is the largest commercial beekeeping operation in the USA (and therefore presumably the world). Unsurprisingly, they’re too busy doing colony inspections to update their website, but you can read more about Richard Adee here.

{{4}}: I’m hoping to keep this simple by omitting pesky things like units … for those who are interested a virus, such as deformed wing virus, acquires 1 nucleotide change in ~10,000 nucleotides copied. Since the virus genome is ~10,000 nucleotides in length this means that every genome differs (randomly) by one nucleotide from every other genome.

{{5}}: And, just so you appreciate the scale here … the honey bee genome contains 10,000 different genes and is ~23 million times larger than the genome of deformed wing virus.

{{6}}: To put your 1 in 22 million chance in context … there’s a 1 in 10 million chance you’ll be struck by lightning and 1 in 250,000 chance of being killed at home by a crashing aeroplane. You might be wiser to spend your £2 on a hard hat … a hard rubber hat.

{{7}}: Bak et al., (2018) The condition of honey bee colonies (Apis mellifera) treated for Varroa destructor by different methods. J. Apicultural Res. 57:674-681. PDF of Bak et al., available here for download.

{{8}}: These could not be counted in oxalic acid treated colonies in late summer, presumably because they sprayed a 3.5% solution onto frames which would damage unsealed brood and eggs. This is not a treatment regime approved in the UK.

{{9}}: In addition, there is evidence that the mite has evolved to be avirulent, rather than the bees acquiring resistance. Same overall result, very different reason. I’ll deal with this sometime in the future, it’s another interesting story.

{{10}}: Since the word count has just crept over 2000 I’ll save a discussion of this interesting study for sometime in the future.

Join the discussion ...