November interlude

November is one of those 'in between' months as far as my beekeeping goes. The season is essentially over, with just a few tasks to complete, but it's too early to work up much enthusiasm for the season ahead.

In Scotland, March feels much the same - there are things to do, but it's too early to do anything major. Of course, readers from New Zealand or East Suffolk will be busy rearing queens in November and March respectively, but I can only really write about our season here at 55.5°N in the Scottish Borders {{1}}.

So, November is an interlude between the work of the beekeeping season (queen rearing, honey production, swarm control, disease management) and the make-work of the winter months (frame building, cleaning equipment, planning and scheming). In fairness, some of this isn't make-work ... I can't remember a season when I've had enough frames prepared, but it's difficult to get excited about an afternoon of frame building when the weather is cold, the fingertips are numb, the dexterity is even more limited than usual and the hammer is misdirected.

Ouch!

The best understood meaning of interlude, and the way it's used in the paragraph above, is:

An interval in the course of some action or event; an intervening time or space of a different character or sort (c.1750's).

However, there is an alternative, and much older meaning:

A short farcical entertainment performed between the acts of a medieval mystery or morality play (early 14th Century).

This meaning clearly doesn't apply ... the farcical entertainment in my year it usually the active beekeeping season where "if it can go wrong, it probably already has" often applies. What's more, my beekeeping season is neither morality play or medieval mystery, though many things the bees do is a mystery.

I write these pages to try and convince myself I know what I'm doing ... or make it sound as though I do to others.

So, what have I been doing?

Apivar strip removal

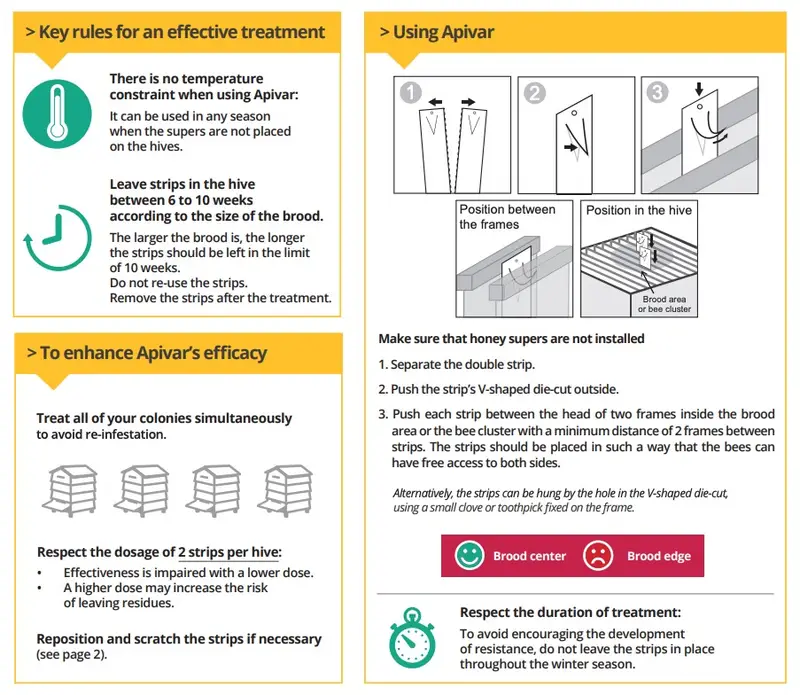

A couple of weeks few months ago {{2}} I wrote about resistance to Amitraz, the active ingredient in Apivar. Although resistance has been convincingly demonstrated independently several times, it remains relatively poorly understood and has some really interesting characteristics.

However, being interesting doesn't alter the fact that it's also highly undesirable, and it is important to minimise the chances of amitraz resistance developing by using Apivar properly, which means as described in the instructions.

Since Apivar only kills phoretic mites (i.e. it does not get through cappings to target mites on developing brood) the strips must be present in the hive for 6-10 weeks, with the longer period indicated for colonies with lots of brood.

After 10 weeks the level of amitraz in the strips is reduced, meaning that mites are probably only exposed to a sub-lethal dose of the miticide.

This is precisely the scenario that can lead to the development of resistance; mites which have developed partial resistance escape being slaughtered and go on to reproduce, with the likelihood that increased resistance then develops. So, the strips need to be removed and not left in overwinter ...

Therefore, during a long road trip to deliver honey and collect yet more stuff from the west coast, I also visited to check on my colonies in Fife and remove the Apivar strips that went in at the end of the third full week in August {{3}}.

In and out ...

It was a gorgeous day, unseasonably sunny and warm. The bees were flying well and - unusually for this time of the year - still collecting a bit of pollen. Ivy perhaps, but my colourblindness means I don't trust my ability to discriminate between a dull yellowy-green and a dull greeny-yellow.

Sheffield BKA have a neat pollen chart online where you can switch on or off pollen 'colour-swatches' for a particular time of the season ... great, except to my eyes the ivy, knapweed, Californian poppy, hogweed and borage all look indistinguishable 😞 {{4}}.

Removing the strips takes just seconds, so poor weather should never be an excuse to not remove them. It simply involves setting aside the roof and crownboard, smoking the colony gently, prising the frames apart where the two strips are located, wiggling the strips out carefully to avoid crushing bees, and closing everything up again.

Two things (in addition to balmy weather) make the job easier:

- repositioning the strips adjacent to the shrinking broodnest about halfway through the treatment period. This means that the bees have had less time to gum everything up with propolis.

- hanging the strips from a cocktail stick (or similar ... I've used paperclips, buddleja twigs or matches) between the frames, rather than relying on the V-shaped tag die-cut into the strip. I've found that the latter 'forces' the strip tight against one of the flanking frames; inevitably this means it gets all gummed up with propolis or wax, and - not obvious but certainly undesirable - the bees have limited access to one side of the strip.

... and have a rummage about

It was such a nice day that I took the opportunity to look at a frame from the middle of the brood box in a few hives. To my considerable surprise, one contained a small patch of brood, perhaps the size of the palm of my hand.

These colonies were reasonably strong, but not unusually so for the time of the year. The last month or two haven't been unseasonably warm (or cold) so I expected the state of the brood to be as I described as recently as last week:

my colonies are routinely broodless for much of November

Famous last words 😉.

In fairness, there was still the best part of three weeks of November still to go, so perhaps that small patch was the 'last gasp' before the queen shuts down for a well-earned rest.

I didn't go through the remainder of the frames. As soon as any clouds drifted over the bees started to remind me that, although it looked like a really nice day, it was November and they would really appreciate me putting the roof back on and clearing off back to wherever I came from.

Most of the brood present was sealed, but there was an outer ring of uncapped late-stage larvae {{5}}. Once capped, this will take ~12 days before emergence, so I'll hold off doing the winter oxalic acid treatment for at least another fortnight.

It's worth reiterating, if the colony is broodless there's little to be gained from delaying the winter oxalic acid treatment. The purpose of this treatment is to mop up as many mites as possible that escaped the late summer Apivar (or whatever) treatment, minimising mite numbers for the start of the next season. In a broodless colony, mites cannot reproduce, but soon after the queen starts laying again the mites will be able to hide again in capped cells.

DOA

In a second apiary the bees were again flying well, with the exception of one hive.

This colony had attempted to supersede the 'old' queen quite late in the season. I'd found the old queen and her intended replacement - a nervous, scuttling, virgin - together in the hive at the last proper inspection. However, that was weeks ago, and I'd only opened the box once in the intervening period to reposition the Apivar strips, late one afternoon ... not ideal conditions to search for a new laying queen.

In late September I described the state of the broodnest in these hives as ...

... no more than one or two frames, several had no obvious sealed brood and none had more than 3 frames.

In August this semi-moribund colony was as strong as any other in the apiary. In late September it was appreciably smaller, but I justified this (ever the optimist!) in terms of the new queen just getting started.

However, the quiet hive entrance made me suspicious that things had all gone 'Pete Tong'.

Once I opened the box, even before seeing the bees, I was certain.

Under the crownboard, was a largely untouched block of fondant. Queenless colonies do not take stores down for the winter.

Having removed the fondant I found a pathetic cluster of bees no larger than a grapefruit, and many of them were drones.

Clearly the old queen had failed or died, the new queen had failed to mate, and the colony was in terminal decline.

Laying workers

There were a couple of dozen scattered bullet-shaped drone brood cells in worker comb, indicating that the colony had developed at least some laying workers. However, the amount of laying worker brood was insufficient to account for the number of adult drones in the colony.

The amount of laying worker brood was also significantly less than I'd have expected midseason from a terminally queenless colony.

I expect that either:

- laying worker development is somehow temperature-dependent or otherwise inhibited late in the season, or

- the laying workers didn't develop until the colony had been queenless for a very long time and the population had already shrunk considerably

Any one of the three symptoms - drones in the hive, uneaten stores (and a light brood box) or a quiet hive entrance on a good day - are a cause for concern at the tail end of the season.

All three and it was clearly game over.

I moved the hive a few yards away and shook the bees out. Some should have been able to beg their way in to one of the flanking hives.

If you have livestock, you will have deadstock.

Finally, a few drones in the hive late in the year are nothing to be concerned about ... some seem to hang around for ages, though they are usually gone by Spring.

Brace yourself

I only feed fondant to my colonies in Autumn. I've written about this extensively, so won't rehash the justification which I've found compelling since I first tried it about 15 years ago.

I add a 12.5 kg block of fondant, split in half and opened 'face down' - likely a badly treated book - onto a queen excluder over the brood box. To provide the 'head space' necessary to accommodate the block I either invert one of my perspex crownboards over it, or - since I have less of these than I have hives - an empty super.

If I'm using an empty super, the crownboard goes on top and I close the colony up until they finish the fondant.

Almost always - perhaps ~98% of the time - the bees take the fondant down, emptying the bag completely, and store everything in the brood box.

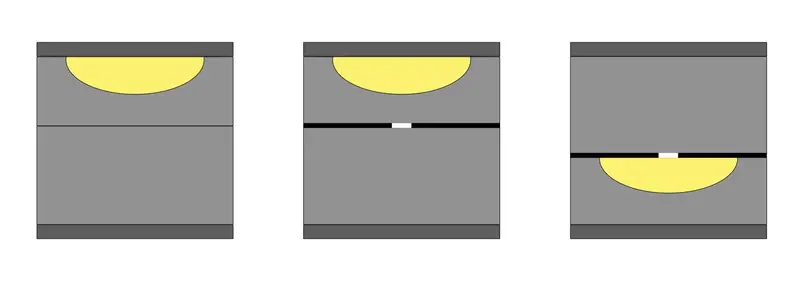

Rarely - by which I mean one colony every 3-4 years (of the 15-20 overwintered each year) - the bees mess about and build a load of brace comb above the block of fondant, hanging down from the crownboard. They only do this when I've used a super to enclose the block of fondant {{6}}.

The strange thing is that the colonies that do this don't appear to be short of space in the brood box when I start feeding them, they're no stronger (or weaker) than the neighbouring well-behaved colonies with which they share the apiary, and that also have a similar 'fondant in an empty super' setup.

They're obviously just being contrary, or they're eejits.

Intervene or not?

So, what's the best course of action?

- Do I cut off the brace comb and risk potentially leaving them short of stores, as well as making a really sticky mess directly over the brood nest?

- Perhaps I should shift the crownboard and attached brace comb, together with the enclosing super, above an additional crownboard with a small hole for the bees to traverse (middle diagram, below). This usually encourages them (I've heard it described as "making them 'think' the stores are outside the hive" ... a little too much anthropomorphising if you ask me 😉) to take the stores down into the brood box.

- Alternatively, maybe the best course of action is to move the crownboard, attached brace comb and enclosing super below the brood box? Since the bees 'prefer' (a little too much anthropomorphising if you ask me 😉) stores to the sides and above the cluster, they should empty the brace comb, taking the stores up into the brood box.

I've done all three at one time or another, with varying degrees of success.

The first is messy, though it's generally not fatal. It always feels like a waste to me.

The second means you need a spare crownboard with a suitable hole. I sometimes have the former with me, and I made a few pieces of drilled perspex to reduce the hole to just 1 cm in the hope that made the bees 'think' that the stores were definitely outside the hive. I've had variable success with this ... if it gets cool, the bees seem to quickly abandon the stores overhead.

The final method - nadiring the stores - necessitates that the bees have left, or you can engineer, a hole through the crownboard for them to traverse. You also need another spare crownboard.

Actually, there's also a fourth method ... do precisely nothing and hope for the best, which is what I did this year 😉.

Nothing ventured, nothing gained

Sponsor The Apiarist

The Apiarist covers 'the science, art and practice of sustainable beekeeping ... so much more than honey' and I write to assuage my guilt for not carrying enough spare crownboards to sort out the brace comb in contrary colonies.

If you found this post helpful, interesting or entertaining then please consider sponsoring The Apiarist. Sponsorship costs less than £1/week annually, or about four sheets of foundation monthly. Sponsors help ensure the weekly posts appear, have access to an increasing number of sponsor-only content (those starred ⭐ in the lists of posts), and receive my undying gratitude. Some of these things are more valuable than others.

Alternatively, you can help reduce my caffeine overdraft ... and please spread the word to encourage others to subscribe.

Thank you.

{{1}}: Now, more or less settled, with 90% of the move completed and only one more trip scheduled to the West coast.

{{2}}: Blimey, where did the intervening time go?

{{3}}: Yes, I know I was 2 days late in removing the strips, but as long as you don't tell the bee inspectors no one will be any the wiser 😜.

{{4}}: I'm not after sympathy ... remember, François Huber was a great beekeeper and he was blind.

{{5}}: I didn't both searching for eggs or brushing bees off the frames.

{{6}}: Obviously, there's only just enough space under an inverted perspex crownboard for a complete block of fondant.

Join the discussion ...