Right here, right now

In February 2016 I posted an article on “When to treat“ colonies with miticides. It was read by subscribers, generated a bit of discussion – in particular on Apiguard use – and then disappeared into the howling wilderness that is the interwebs …

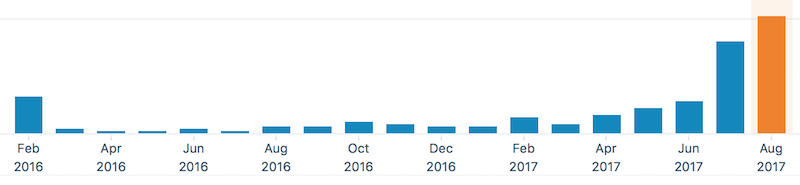

Google hides the searches that drives most of the website traffic to this site. However, it has been found … as is clear from the access stats (below), it is now being accessed extensively.

This reflects the change in the seasons as beekeepers turn their thoughts from harvesting honey to protecting their colonies from the ravages of Varroa and the viruses it transmits.

It’s worth reiterating it here, though this won’t be news to regular readers, Varroa itself is probably not the problem. The problem is the smorgasbord of viruses that Varroa transmits when feeding on the haemolymph (blood) of honey bee pupae.

Benign and virulent

Most important of these viruses is deformed wing virus (DWV). This virus has a sort of Jekyll and Hyde personality. It’s probably present in all honey bees, transmitted between bees while larvae are being reared and during trophylaxis (the regurgitation of liquid food between bees). Under these conditions, and in the absence of Varroa the virus is probably benign.

Of course, it’s difficult to test whether it is really benign as there probably aren’t any bees that lack DWV. Even bees that have never been exposed to Varroa, such as the black bees on Colonsay, have DWV. Let’s assume that, even if not benign, it has minimal detrimental effect on the bees.

Varroa changes the route by which DWV is transmitted. Instead of being orally transferred – a route the bees have probably evolved to cope with – Varroa bypasses any defence mechanisms by ‘injecting’ DWV directly into the blood. Under these conditions DWV reproduces rampantly – for reasons that have yet to be determined – causing the ‘deformed wing’ symptoms most beekeepers are familiar with.

Symptomatic adult, or recently emerged, bees can contribute little or nothing to the colony.

Live fast, die young†

But there’s more bad news. Asymptomatic adult bees with high levels of DWV have a shorter lifespan and die prematurely. This is perhaps not an issue during the heady days of summer when the turnover of worker bees is at its height – the queen is laying well, perhaps 1500-2000 eggs per day, the colony is bulging and individual workers “live fast and die young” after about 6 weeks.

Formally, I don’t think it’s been shown that mid-season workers have a shorter life span when they have high levels of DWV. What is known, and what is much more important, is that winter bees die prematurely if their DWV levels are high.

Winter bees are the ones with high levels of fat in their bodies. These are the bees that get the colony through the winter. Some might live for 5-6 months in the UK, and it’s known they can live for up to 9 months. If these bees die early, in the absence of any significant brood rearing, the colony dwindles and dies.

Game over.

Preventing the inevitable

Varroa transmits DWV and results in high levels of DWV. High levels of DWV in winter bees shortens their lifespan and results in colony losses. How can you prevent the inevitable?

In the absence of ways to directly control DWV levels (these are in development but you’re then tackling the symptom, not the cause) the only way to do this is to prevent the transmission of DWV to the winter bees by Varroa in the first place.

And you do this by applying effective miticides early enough that the winter bees are protected from exposure to Varroa, and the viruses it transmits.

How early is early?

I discussed this in the earlier article and am working on a more nuanced version at the moment. Essentially – and I’m writing this in mid-August – the answer is now or very soon.

In the definitive publication demonstrating the premature death of winter bees by DWV, Peter Neumann and colleagues detected a measurable reduction in longevity as early as November in the colonies they studied. These bees were age-marked and had emerged 50 days earlier. The eggs had therefore been laid in the first week of September … and been capped (together with any Varroa) as pupae in mid-September.

Therefore, treatments to reduce Varroa should be completed by mid-September to protect the winter bees. Since many treatments take ~4 weeks the time to treat is right now.

Caveats

There’s climatic variation between parts of the UK and Bern, where the study by Peter Neumann was conducted. There’s also seasonal variation year on year.

In the balmy South the dates will be later than in the frigid North. In cool years with an early autumn they will be earlier, whereas an Indian summer will delay the need to treat.

Treatments are generally incompatible with a honey flow. If you take your bees to the heather you have to balance collecting a late heather crop with protecting the bees from the ravages of Varroa.

it’s not possible, or wise, to be dogmatic about precise dates … other than to say that miticide treatment is generally required earlier than you think to protect the winter bees from DWV.

Better late than never?

Well, yes, but the damage may well have been done.

The annual survey of beekeepers in Scotland regularly includes significant numbers using Apiguard in October. Close, but no cigar‡ (actually, not even close) … it’s probably too late to reduce Varroa levels in a meaningful way, and it’s unlikely to be effective anyway as Apiguard needs average temperatures around 15°C.

All of the comments above on the timing of treatment make the assumption that the treatment is effective – the right dose, the right duration, the absence of resistance etc.

Finally, it’s worth noting that starting treatment in mid/late August does not reduce Varroa levels to the lowest achievable levels. Treating later in the year does this, because more mites are phoretic and ‘reachable’ by the treatment. To reduce mite levels to the minimum you also have to also treat midwinter … something for another post.

† Live fast, die young was the title of a biography of the actor James Dean by James Gilmore. It’s a popular phrase, being used for a movie and several song titles. The extended version Live fast, die young and have a good looking corpse, often wrongly attributed to James Dean, actually came from the 1947 book Knock on Any Door by Willard Motley.

‡ Close but no cigar is a mid-20 phrase from the USA. It dates back to the time when fairground stalls gave out cigars as prizes.

Colophon

Right here, right now is a song released in April ’99 by Fatboy Slim (Norman Cook) from the album You’ve come a long way, baby‘. If you appreciate evolution you’ll enjoy the video …

… but you’ll need to like beat/dance music to appreciate the track.

Join the discussion ...