Adultery

Synopsis : Fake news. All tested UK honey exports to the EU were ‘suspicious’ as were almost 50% of EU honey imports. Honey adulteration and the global trade in fake honey.

Introduction

One of the reasons you won’t read articles here on Buckfast bees, or Taranov swarm control, or queen instrumental insemination is that I’ve no experience of them.

I only write about subjects that I have practical experience with.

What’s the point of regurgitating stuff that’s available elsewhere? There’s far too much of that already.

But todays sordid tale about cheating and dishonesty is an exception.

Most readers will be familiar with adultery, at least the meaning of the word … but it has another meaning (now obsolete), that of debasement or corruption.

You’re probably more familiar with the term adulteration.

Although the etymology of adultery and adulteration overlap – both are derived from Latin via Middle French – their meanings have diverged. Adultery now refers almost exclusively to marital infidelity, whereas adulteration means:

The action or an act of adulterating, corrupting, contaminating, or debasing; (now esp.) the practice or process of making something poorer in quality or unusable for its original purpose by the addition of another substance.

Adultery was to pique your interest.

Adulteration (of honey) by the addition of cheap sugar syrup should disgust or infuriate you.

Honey is an expensive product; it is only produced by bees, its extraction is labour intensive and it has a premium status. Therefore there is profit to be made by fraudsters who ‘cut’ the honey with inexpensive syrups, so increasing their profit.

Honey

But there’s an additional issue with honey. In many countries, demand far outstrips domestic production. Consequently there’s a huge international trade in honey … and where you have complex supply chains, with production, packing and sale possibly involving several countries, there are opportunities for significant profits to be made by those willing to bend the rules, or not look too closely at the contents, certification or country of origin.

What is honey?

A convenient legal definition of honey is in The Honey (England) Regulations 2015 which covers the sale, labelling and composition of honey:

In these Regulations “honey” means the natural sweet substance produced by Apis mellifera bees from the nectar of plants or from secretions of living parts of plants or excretions of plant-sucking insects on the living parts of plants which the bees collect, transform by combining with specific substances of their own, deposit, dehydrate, store and leave in honeycombs to ripen and mature.

The same document defines the physicochemical properties of honey such as the sugar (sucrose and fructose) content, moisture content, electrical conductivity and diastase activity (amongst other things).

If you read these you will realise that honey is actually rather difficult to define in these terms. It’s quite a variable product. Blossom honey should contain 60g/100g of sugar, of which no more that 5g/100g should be sucrose … except for a list of about 9 different (very delicious) honeys which have 2-3 times that amount of sucrose.

And, because of this variation and because the composition is broadly defined and can be chemically reproduced you get products such as Melibio’s Honey Made Without Bees. This is made from ‘plants and natural ingredients’ which ‘looks, tastes and acts like bee-made honey’.

Except it is not honey.

That’s because, even if it were ‘molecularly identical’ as is claimed in some reviews of Melibio’s “honey”, it’s not made by bees, and the definition of honey {{1}} covers both what honey is made from and how it is made.

And the latter involves the activity of the bees who ‘collect, transform by combining with specific substances of their own, deposit, dehydrate, store and leave in honeycombs to ripen and mature’.

What isn’t honey

Therefore Melibio’s Honey Made Without Bees is not honey – presumably explaining why the product launching in Europe is called ‘Ohney’ {{2}}.

And, using exactly the same definition listed above, any ‘honey’ that has been adulterated by the addition of inexpensive sugar syrups, effectively bulking out the product and increasing the profit margin, is also not honey.

This adulteration of honey, particularly – though certainly not exclusively – of inexpensive supermarket honeys, regularly makes the news headlines, and did again last week with the publication of an EU report on the analytical testing results of imported honey (Ždiniaková et al., 2023).

All the important news (The Guardian, 26/3/23)

At one point it was the most read and most shared article in The Guardian … exactly the sort of thing you’d expect the Guardian-reading, tofu-eating wokerati {{3}} to be concerned about.

The Telegraph also reported the story (as did just about every other news outlet … after all the bees are doomed and so, seemingly, is the honey for our porridge) under the somewhat misleading headline ’Why all UK honey fails EU authenticity tests’.

Nearly, but not quite right

And then the Chinese-whisper, echo-chamber that is Twitter bastardised and bowdlerised the headlines, getting some of the results wrong, misinterpreting the conclusions or selectively emphasising parts of the press release.

But did any of them read the actual EU report?

I rather suspect not … but I have.

It is well written and makes interesting reading.

It is a damning indictment of the international honey trade and the honey packing industry.

The underlying science is also interesting. There’s an ‘arms race’ between the honey adulterators and the scientists attempting to detect fake honey. The old detection methods no longer work dependably. New approaches are needed.

Honey is not “honey”

I don’t want to keep writing adulterated honey so will try and use “honey” to indicate it instead, reserving honey (with no speech marks) for the real deal, the unadulterated, delicious, premium product.

“Honey” might look and taste like honey, but is bulked out with sugar syrup so is not honey.

Remember also that there are significant problems with contamination of honey – for example with antibiotics or pesticides – but these are outside the scope of both this EU report and this post. A recent report showed that 84% of honey sampled in China was contaminated with antibiotics (Wang et al., 2022).

The “honey” you purchase for £1 that contains the ’Produce of EU and non-EU countries’ may therefore not only predominantly contain rice syrup, but it might also contain traces of tetracycline and a cocktail of other antibiotics {{4}}.

Yummy 🙁 .

The problem and the opportunity

Europe consumes more honey than it produces domestically. Therefore a considerable amount of honey is imported and there is a huge international trade in honey (valued at ~€1.7bn).

This is big business.

Europe produces about a quarter of a million tonnes of honey and imports a further 175-200,000 tonnes.

175,000 tonnes of honey has a gross value of about €400M. Imported honey costs ~€2.4/kg {{5}}.

In contrast, rice syrup costs as little €0.4/kg when purchased in bulk.

So if you dilute honey 50:50 by weight with rice syrup and sell the resulting “honey” for €2.4/kg you’ll make a profit of €1/kg. This is not the ‘drug dealer level of profits’ claimed on Twitter, but it is a lot of money if you’re selling 500 tonnes of the stuff.

That’s quite an incentive.

If you assume that ~50% of EU “honey” imports are adulterated (they are, see below) by as little as 50% rice syrup, then you’re talking about an annual profit from fraud of about €100M.

If this trade in fraudulently adulterated “honey” were reproduced on a global scale – and there’s every reason to think it is – then it’s approaching a billion euros per annum in profit.

The current study

In 2015-17 the EU conducted a survey of adulterated honey. 14% of the samples tested were suspicious as they did not conform to the expected purity benchmarks {{6}}. This prompted follow-up discussions and a subsequent EU coordinated action to ‘deter certain fraudulent practices in the honey sector’, with the recent widely publicised report on the analytical testing of honey imports to 15 EU member countries together with Switzerland and Norway.

A total of 320 consignments of honey were tested, the majority following sampling at border crossing points.

All sampling took place in the 11 weeks between late October 2021 and mid February 2022. In contrast to some of the claims on Twitter this is not ’old news’, it pretty much reflects the current state of the art.

The UK is of course now outside the EU, but the UK does export honey to the EU.

There are several UK companies that specialise in honey packing – essentially jarring bulk honey – for the domestic and export market. Some of these companies are listed by the British Honey Importers and Packers Association, but there are others as well (including some well-known names).

Ten consignments of honey imported to the EU from the UK were tested as part of this study.

And – just to be absolutely clear – none of the honey exporters were identified in the report. All could have originated from a single exporter, or all could be different. The exporter(s) may or may not be a member of BHIPA. I’m not apportioning blame, I’m just discussing the scale of the fraud.

Detecting fake honey

I’ve described what honey is and is not above. How do you discriminate between real honey and adulterated “honey”?

Four methods were used in this study:

- Elemental Analyser/Liquid Chromatography – Isotope Ratio Mass Spectrometry (EA/LC-IRMS): which detects the ratios of two stable isotopes of carbon that are present in protein and sugars in the sample. This is a well established method and is typically used to detect honey adulterated with maize starch or sugarcane.

- High-Performance Anion Exchange Chromatography Pulsed Amperometric Detector (HPAEC-PAD): which detects the degree of polymerisation of polysaccharides.

- Liquid Chromatography – High Resolution Mass Spectrometry (LC-HRMS): used for the detection of compounds like difructose anhydride or 2-Acetylfuran-3-glucopyranoside which are markers of adulteration.

- Proton Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (1H-NMR) Spectroscopy: which is used to detect adulteration with mannose and involves comparison with a database of over 28 thousand reference samples of honey.

I bet you’re glad you asked 😉 .

The key point here is that the methods identify different strategies by which “honey” is adulterated. It should be noted that the methods are qualitative, not quantitative; they can detect adulterated honey, but cannot necessarily distinguish between “honey” that is 10% rice syrup or 90% rice syrup.

Perhaps a moot point as neither are honey 😉 .

EA/LC-IRMS – a method used widely in the past – turned out to be ineffective in detecting suspicious “honey” that was positive (i.e. adulterated) using other methods. This reflects changes in practice by those adulterating the honey as they try and outwit the quality control tests.

If you like acronyms and chemistry – I don’t – the report is fully referenced and you can read lots more about the detection methods if you check the bibliography.

Where does the honey originate from and end up?

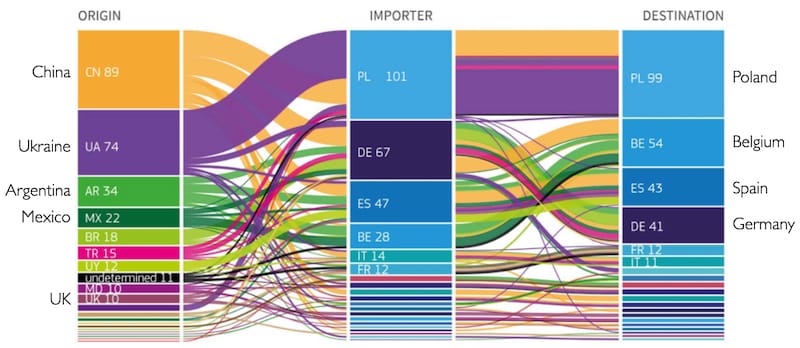

The second figure in the report is really striking. It’s a graph showing the origin of the honey, the country it was imported to, and its final destination in the EU.

Origin, importer and destination for non-EU sourced honey

Of the 320 samples tested, 89 (28%) were from China which is unsurprising at it is the largest global honey exporter. Ukraine was the second most common source (remember, data collection predated the invasion by Russia and may well be very different now) followed by three central or South American countries. These top 5 comprised 74% of all samples tested.

Chinese honey is imported to just about every one of the 17 countries from which samples were collected – see the medusoid-like pattern of lines emerging from the Chinese block on the left.

Other than honey imported to Poland (which interestingly largely stays in Poland) the honey imported into other countries may not stay in the initial country of import. For example, Belgium only imported 28/320 samples, but 54/320 were destined for Belgium.

The 10 samples imported from the UK appear to have gone to a variety of destinations, but the spaghetti-like lines are impossible to disentangle {{7}}.

Suspicious samples

46% of the 320 samples tested contained one or more (2+ in 44% of samples) markers of adulteration, so were considered ’suspicious’. The top 5 sources (by percentage, but ignoring countries with <5 samples) for dodgy-looking “honey” were Mexico (27%), Brazil (31%), China (74%), Turkey (93%) … and the UK (100%).

Unsurprisingly considering the scale of global exports, the largest number of suspicious samples originated in China (66/89).

Obviously (as an infinitesimally small scale UK honey producer myself) the 100% score for UK honey is disappointing.

Does this mean that “ … all UK honey fails EU authenticity tests … ” as the headline in The Telegraph states?

Of course not.

Firstly, the honey exported by the UK to the EU may not be UK honey. The report includes the statement that:

… the available traceability information suggests that this could be … honey produced in other countries but further processed and re-exported by the United Kingdom.

Secondly, only 10 samples were tested and – as indicated above – there is no further information on the exporter(s).

Suspicious mind

The UK consumes a lot of honey “honey”.

It is claimed to be the UK’s most popular spread, with ~30,000 tonnes consumed annually. This figure is far in excess of our domestic honey production which is probably 3-6,000 tonnes.

I’ve struggled to find a post-Brexit figure for this that wasn’t behind a paywall. However, there are about 250,000 hives in the UK and the average annual yield is reported to be ~11 kg per hive (i.e. 2,750 tonnes). Obviously many produce considerably more than this and it will vary from year to year, but I’d be amazed if we produce more than 20% of the total amount consumed annually.

So the remainder must be imported. Indeed, it’s reported that the UK imports about 38,000 tonnes of Chinese honey per year, some of which may be re-exported to the EU.

So we’re left with these sobering facts:

- At least 46% of EU imported honeys are doctored by the addition of something that isn’t honey, but is probably syrup from rice, wheat or sugar beet.

- The worlds largest honey exporter (China) has one of the highest levels of honey adulteration (~75%).

- The UK probably imports 80-90% of the honey it consumes, and a very significant proportion of this will originate – directly or indirectly – from China. Directly or indirectly because China has previously bypassed anti-dumping laws in the USA by selling through third countries.

- There’s every reason to suspect that a significant proportion of imported honey is adulterated.

- All of the “honey” tested that was exported from the UK to the EU was considered dubious when tested.

Call me suspicious, but if the jar states ’Produce of EU and non-EU countries’ I think it is highly likely to contain adulterated honey.

Whatever the price.

Who is at fault here?

Honey fraud is a complex issue.

Detecting it involves rigorous testing and is not inexpensive. It’s also not certain that every example of adulterated honey can be detected;

- firstly, there will be a lower threshold of detection below which you cannot be certain it has been doctored.

- secondly, those adulterating the honey are quite possibly one step ahead of those attempting to detect it.

So, whilst acknowledging that there are problems and complexity, does that mean we (‘we’ meaning consumers, producers, regulators … or anyone involved or interested in the entire process, from the beehive to the bowl of porridge) shouldn’t try and do something about it?

Producers

Clearly, fraudulently selling syrup mixtures as honey is the primary cause of the problem. If this didn’t happen then it doesn’t matter what was written on the jar … you could trust that it was pure honey.

Of course that’s never going to happen. There’s a long and sordid history of cheap, sub-standard and unsafe foods being sold to unwitting consumers having entered the food chain fraudulently.

In case you’ve forgotten, think back to the horsemeat scandal in 2013. Horse (and pig) meat was being sold as beef and incorporated into a range in cheap products like burgers and ready-meals. Like honey, the trade was international and convoluted. Like honey, there were significant profits to be made.

Importer and/or packers

I don’t know enough about the international trade in honey to know if these are one and the same, or if importers sell on to the packers {{8}}.

It doesn’t matter.

I’m sure most import and pack with the best intentions of not fraudulently misrepresenting the product. However, I’m also sure that some take more notice of the profit margin and don’t look too closely at the product, or routinely get imported honey tested to verify ‘it is what it says on the tin’ {{9}}.

This EU report is not the first time that imported “honey” has been shown to be largely suspect. Knowing this, how many importers/packers have introduced meaningful testing?

Knowing now that ~75% of imported Chinese honey is suspect, how many importers/packers will source their honey elsewhere?

How many of the UK packers/exporters that provided the 10 samples shown to be suspect in this recent EU study are changing their business practices?

I fear I know the answer to most of these questions … 🙁 .

Supermarkets/retailers

”Pile it high, sell it cheap”.

Supermarkets compete heavily on price but have repeatedly been shown in the past to sell “honey” that isn’t anything of the sort. Some has been withdrawn from sale.

What on earth makes them think that the “honey” they now sell for 75 p is different from the similarly priced syrup they mis-sold 5 years ago and had to withdraw from sale?

I’m afraid the answer is probably a combination of naivety and greed.

When challenged supermarkets claim they can trace the supply ‘from the beekeeper to customer’, or that it can be ’traced back to the beekeeper’.

Sounds good, doesn’t it?

I do not believe them.

Honey is traded in multiples of tonnes. We imported 38,000 tonnes from China in 2022. Even if you only assume that it contained 19,000 tonnes of actual honey ( 🙁 ) that must originate from a very large number of beekeepers.

What is the name of the beekeeper who produced this honey?

Can the beekeepers who produced the ‘honey’ in the 75 p jar of multifloral honey be traced?

Beekeepers (plural) because the honey is a blend anyway and is the ’Produce of EU and non-EU countries’.

Not a chance.

By the way … I’m not suggesting that the supermarkets stop selling this stuff … instead, call it syrup (or anything but honey {{10}} ). I’m well aware that some customers a) cannot afford £5 a jar, and b) are perfectly happy with the flavour of the 75 p jar of “honey” … just be honest, it’s not honey.

Food Standards Agency (FSA)

The FSA have long been aware that thousands of tonnes of rice/maize/wheat etc. syrup are probably being imported into the UK and fraudulently sold on as honey. Yes, the importers/packers might not know that it’s rice syrup, but the end result is that the customer is being sold a lie.

How many samples do the FSA test?

If the EU can detect honey adulteration in ~50% of imports, how close to this figure do the FSA get? Is it higher or lower? If lower, are they using the right tests, or are they still working with tests that were long-ago rendered obsolete due to different syrups being used for adulteration?

If higher, why is there not more enforcement? Banning imports from certain sources, with penalties for importers, packers or supermarkets?

When recently challenged about this the Government’s response included the following:

The Government disputes assertions that honey imports to the UK are being adulterated on an industrial scale. Allegations in the media that a small number of specific blended honeys sold in the UK were fraudulent have been fully investigated by the relevant Local Authorities and concluded that there was insufficient evidence to indicate fraud or non-compliance.

We are confident the honey regulations and enforcement of those regulations are fit for purpose but acknowledge honey is a complex natural product and analysis to determine if honey has been adulterated can often be challenging.

It will be interesting to see how they respond to 100% of UK to EU exports being considered suspicious … but I’m not holding my breath.

Purchaser

If the price looks too good to be true … it is.

My advice to anyone that asks is to never buy honey that is either inexpensive or doesn’t list a single source on the jar.

Unless that source is ‘China’ … or now – if the customer is in Paris, or Stuttgart, or Milan – ‘United Kingdom’ 🙁 .

What’s inexpensive? Perhaps 1 pence/gram, I don’t know.

If the honey carries the label ’Produce of EU and non-EU countries’ buy something else.

Always.

If you want honey, that is … 😉 .

Conclusion

It’s been profoundly depressing writing this post.

It’s probably not been a bundle of laughs reading it.

There’s currently a petition to encourage the Government to “Require honey labels to reflect all countries of origin of the honey”. You can find it here and the {{11}} quote above about the FSA comes from the initial response to the petition. The petition closes in about two weeks and has currently been signed by ~13,000 people.

Please sign it.

I’ve signed it though I remain to be convinced that this will reduce honey adulteration, though that isn’t the primary goal of the petition (which is about informed customer choice). The initial line of the Government’s response is:

The Government takes food fraud seriously and is working to ensure honey meets our high standards. Country of origin labelling is not a suitable means for determining if a food is subject to fraud.

I completely agree with the second sentence.

I’d like to believe the first … but I don’t.

Improved honey labelling might make customers think twice about what they’re buying, but changing the label from ‘honey’ to ‘syrup’ is likely to have a greater effect.

I would like honey labelling to be improved from the catch-all of ’Produce of EU and non-EU countries’.

However, until that happens, ’Produce of EU and non-EU countries’ is sufficient information for me. It tells me that the honey comes from a variety of sources {{12}}, that the most likely ‘non-EU country’ is China and that there’s about a 75% chance that the Chinese honey component is adulterated with rice, wheat or sugar beet syrup.

Is it honey?

Probably not.

References

Ždiniaková, T., Lörchner, C., De Rudder, O., Dimitrova, T., Kaklamanos, G., et al. (2023) EU coordinated action to deter certain fraudulent practices in the honey sector: analytical testing results of imported honey. Publications Office of the European Union, LU. https://data.europa.eu/doi/10.2760/184511.

Wang, Y., Dong, X., Han, M., Yang, Z., Wang, Y., Qian, L., et al. (2022) Antibiotic residues in honey in the Chinese market and human health risk assessment. Journal of Hazardous Materials 440: 129815 https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0304389422016089.

{{1}}: At least here in the UK.

{{2}}: See what they did there?

{{3}}: Caution … the Daily Mail … don’t say I didn’t warn you.

{{4}}: Of course, I don’t expect any readers of this site – who are predominantly beekeepers – to buy this stuff. For the purpose of research I went to a supermarket last weekend to buy some, but – having already done some background reading – simply couldn’t bring myself to complete the purchase and left the garishly-labelled jars on the shelf.

{{5}}: Note that there could be slight discrepancies in these figures – quantities and values may come from different years. I’ve tried to quote the most recent figures I could find.

{{6}}: See … https://food.ec.europa.eu/safety/eu-agri-food-fraud-network/eu-coordinated-actions/honey-2015-17_en.

{{7}}: Not least because I’m colourblind.

{{8}}: But I suspect the clue is in the name.

{{9}}: Literally, as honey is sold in bulk in large metal drums.

{{10}}: Actually, ’Anything but honey’ is a good name for it.

{{11}}: Underwhelming.

{{12}}: Which may or may not be known to the seller.

Join the discussion ...