Apiary tales

John Gierach died at the age of 78 on the 3rd of October. Gierach was a noted storyteller and admitted 'Trout Bum' which - fittingly - was the title of his third book, published in 1986. It was also the first book of his I read, purchased minutes before boarding the 'red-eye' back from JFK to Heathrow in the late 80s. Since then, I've bought and read - many times - all his books, a collection that now occupies a foot and a half of shelf space.

As that title suggest, Gierach wrote about fishing, primarily for trout with flies and bamboo rods, but it was always the ethos and emotion of the fishing that was more important than the fish. His story entitled 'Carp diem' gives an insight into his gentle wit and would be enjoyed by readers who understand Latin and know the difference between commons, mirrors, grass and Koi's. He wrote over 20 books, almost all of which are collections of short stories. Many contain recurring themes; a blend of gentle hippy wisdom, a penchant for old-fashioned tackle and methods, wry humour and insightful observations on people, the environment and fly fishing.

Gierach was probably the most-read American fishing writer, sometimes matched in quality, though not quantity, by McGuane, Coggins or Rangeley-Wilson {{1}}. I'll miss the biennial appearance of a new book, but now have a reason - not that I needed one - to read the old ones again.

Why, not how?

I might be wrong, but I don't remember a single story from Gierach mentioning bees, beekeeping or even honey ... though coffee does feature prominently, in his travelogues and remote fishing camp tales.

Why then am I writing about him in a beekeeping blog?

Gierach's death made me think about his writing, the pleasure it's brought me over the last four decades, and its contrast with the beekeeping literature. More generally, it made me think about the two pastimes - fly fishing and beekeeping - and the similarities and differences between them.

Don't worry ... this isn't a 'compare and contrast' essay, or a post promoting honey glazed salmon.

Notably, only a couple of Gierach's books could be considered "How to ... " guides {{2}}, though all contain useful information and methodological musings. Instead, the stories often go nowhere, rambling gently around a topic, or from one topic to another, perhaps returning neatly to the start, but always sprinkled with insights or reflective observations.

They are a bit like Garrison Kiellor's Lake Wobegone Days, but with a lot more fish {{3}}.

In contrast, if you look at the shelves - or more likely shelf - of beekeeping books in your local bookshop you'll find a number of "How to ... " guides, but very little discursive writing about beekeeping.

Similarly, if you look at the most-read posts on this website, or at the content of other sites, you'll find numerous descriptions of swarm control methods, mite problems and their management, equipment reviews or guides to solving this or that issue with our bees.

But there's almost nothing about what beekeeping means to the writer, no real discussion of the why's, which are all-but swamped by the how's.

Technology, not philosophy

It appears - at least to me {{4}} - that beekeeping is viewed mainly as a technical exercise; if you observe A, you do B, otherwise you do C ... wait a defined number of days, then do D etc.

Alternatively, purchase X, add Y and - voilà - Z will happen.

Don't get me wrong, there are libraries full of 'How to ... ' books about fishing, describing the latest tackle, methods or flies. There's an entire industry advertising the lightest, slimmest, most accurate fishing rod, that enables you to cast better, further, faster or for longer, and inevitably implying you'll get a creel-full of h u g e fish {{5}}.

Similarly, the latest poly nucs have improved entrances, floors, insulation, roofs, colour-schemes ... and, undoubtedly, profits. Your bees will be cosier, better fed, stronger, less susceptible to disease, calmer or whatever, and your honey crop will be correspondingly larger {{6}}.

However, to my jaundiced eye, there's little difference between the fishing rods sold now, and those I bought three decades ago, or the 'upgraded & improved' nucs available today versus the teetering pile of slightly battered, but nevertheless entirely serviceable, boxes I've been using for years.

Beekeeping is probably less afflicted by whizz-bang new developments in the equipment we use but, if anything, is even more methodological than fishing.

After all, fishing is just 'a jerk on one end of the line waiting for a jerk on the other' {{7}}, whereas beekeeping involves working with the bees, who have their own agenda entirely, largely defined by the climate, the forage and the timing of their development cycle.

Things often do have to be done at the right time, or in the correct order, or the outcome might be unsatisfactory ... or worse.

Philosophy, not technology

But is that all beekeeping is?

Is it just a technical exercise?

Where are the books about the philosophy of our hobby?

I don't even know if philosophy is the correct term here ... ethos isn't quite right either.

Is 'subjective rewards' perhaps more accurate?

It's a bit of a mouthful, and it implicitly suggests that there are only positives.

There aren't.

A typical season will have disappointments, perhaps not many, but some.

And a very poor season will have lots, some of them crushingly bad 😥.

Who writes articles that describe the satisfaction beekeeping brings, the highs and lows, the worries, the gentle - or not so gentle - rollercoaster of emotions through the season or, for that matter, the appreciation it enables of the seasons?

I'm sure they exist, but they don't feature in the bookshops and I rarely see anything like this online {{8}}.

There are books in which beekeeping is a core theme, but it usually provides structure around which the story is built, rather than being the topic of the story. The emotional aspects of beekeeping never feature.

And, of course, there are movies.

Beginners

Perhaps this apparent bias reflects the readership or target audience of most books and websites?

Inevitably, you tend to read avidly around a subject when you know little about it, not once you have gained years of experience.

Beginners understandably want to know how to do things, like stop their colonies swarming, or prepare thin syrup, or treat for mites. They've not got the time or the interest to ponder things like the guilt pangs experienced when you despatch a queen {{9}}, despite the fact the colony she headed were nutters and - literally - 'frightened the horses', as well as jeopardising your relationship with the neighbours.

And what about considering the fate of stowaway workers released from the car miles from their home apiary?

I have a half-finished post on that tucked away somewhere ... but would it be read?

Perhaps this preponderance of guidance really indicates that many beekeepers actually struggle keeping bees, whether healthy, productive or alive. Is this really just an indication of demand and supply? Is the reason I've not written waffly, discursive posts on the "Will she? Won't she?" wait when queen rearing in a poor summer, is because the reader is really just after advice on using dummy boards?

Ignorance is bliss, or not

I wouldn't presume to write a fraction as well as Gierach did but, just as there's more to fly fishing than catching fish {{10}}, there's a lot more to beekeeping than swarm control, queen rearing and honey extraction. So, rather than a technical account of why Taranov swarm control is better than Pagden's method, together with a detailed description of the improvements I've made to the original Taranov board, I'm going to write a bit about those subjective rewards this week.

When I started beekeeping, I had no idea of the enjoyment (and challenges) it would bring me. I liked the idea of bees quietly buzzing around gathering pollen and nectar ... and I liked honey 😄.

In fact, that was the sum total of my knowledge of bees.

I had no idea what was inside a hive, let alone what caused swarming, or what Varroa was, or the weight of a stack of full supers.

Or, for that matter, what a super was.

But a 'Start Beekeeping' course soon fixed that.

It taught me the basics about bees and the equipment I would need.

As an aside, they did the latter really badly.

They underestimated the amount of essential expenditure by thousands. If I'd known I was going to have to spend this much, and that I'd need to build extra outbuildings or rent a shipping container for storage, I'd have taken up something less expensive, like polo.

But I was taught the mechanics of swarm control, the importance of mite management and the 'what happens when' during the season.

All very useful ...

But they never mentioned the fantastic sounds and smell of a full hive, late in the gloaming during a strong honey flow.

On a calm evening, sitting in the apiary under the flittering bats, with the jasmine and vanilla smell of honeysuckle, and the gentle rustlings of small animals in the hedgerow, the rich scent and constant hum of the hive is a truly magical experience.

The bees are busy fanning, evaporating off excess moisture from the nectar, and you can hear them from yards away.

If you've not experienced it, try to.

Swarming

As a beekeeper I go to a reasonable amount of effort to stop my colonies from swarming. I know what I'm doing, and I'm usually successful.

The irony is that there are few sights more enjoyable - at least as far as I'm concerned - than a swarm.

The coordinated chaos is mesmerising.

It's a bittersweet experience. I don't like losing the swarm, but I love watching the colony swarm.

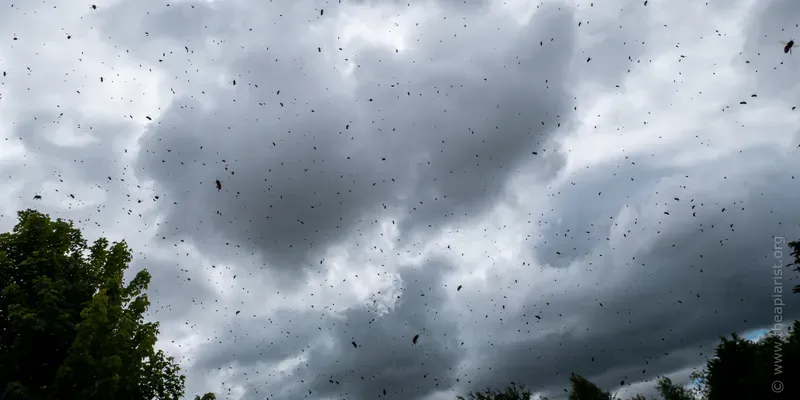

What appears to be just another a busy colony, with bees jostling around the entrance, suddenly transforms itself into whirling maelstrom of insects moving out, up and away {{11}}. They settle somewhere nearby - bivouacking is the correct term - usually out of reach (😞), wait while the scout bees agree on a new nest site, and then move on.

If I'm in the apiary and a swarm emerges I stand there transfixed, marvelling at the sight and sound.

It really is a wonderful experience.

If it's your only colony it might be frustrating watching the workforce disappearing over the fence, but you can take a tiny bit of solace from knowing your colony was strong and healthy enough to swarm in the first place, and from the knowledge that you'll soon have a new queen heading the hive.

At least, you will if you ensure only a single virgin emerges and the weather is kind 😉.

I'll return to queens in a few paragraphs ... and weather.

Incoming!

It's worth remembering that you can almost exactly recapitulate the enjoyable sights and sounds of a swarm by attracting one - to a bait hive - rather than losing one.

I put out bait hives every season and am almost always successful in attracting swarms lost by others (obviously, they're never my bees 😜). Because I'm usually outside, either in the garden or the apiary, during the swarming season I've often been lucky enough to watch a swarm arrive in a bait hive.

Incoming swarm to a bait hive

You can see the coordinated chaos even better than when losing a swarm, as you know where they're headed. All those thousands and thousands of bees were led to the new nest site by the scout bees, from a distance of a few hundred metres to - potentially, though unlikely - many kilometres away.

And you have the added satisfaction of acquiring an extra colony, without climbing any wobbly ladders, or doing a messy 'cut out'.

Furthermore, because your 'Start Beekeeping' course covered the importance of disease monitoring and management (despite never mentioning what an awesome sight a big swarm is) you'll know how to check for brood diseases in between building all those extra supers for the bonanza honey crop you now expect.

Go forth and multiply

Queen rearing is one of the most enjoyable aspects of my beekeeping. The end result - a productive colony headed by a queen reared from a tiny larva I selected, transferred to a strong, well-prepared colony, and then moved to a mating nuc - is very satisfying.

Ted Hooper (in A Guide to Bees and Honey) wrote:

It is a great pity that more beekeepers do not practice queen rearing enjoying the great interest and excitement which goes with it, and the personal satisfaction of seeing a large laying queen which you have been instrumental in producing from the time she was a small larva

But that interest, enjoyment and satisfaction can be mixed up with frustration, gloom and despair.

There are a lot of 'components' to rearing queens; the choice of colony from which larvae are taken, the preparation of the cell raiser, the grafting, getting the cells capped and then distributing the cells for mating.

It sounds easy on paper, but all those components need to work well (or at least work) to be successful, and there is a big investment of time and emotional energy to be made, particularly during your early attempts.

Inevitably, if or when things go wrong, it is disappointing.

Something minor, like only two of your ten grafts being accepted feels like "Harrumph! All that effort for just two queens?" {{12}}

Fortunately, that type of minor setback can usually be overcome by simply repeating the grafting immediately, feeding some syrup and accepting that - if it was easy - everyone would be doing it (they're not ... I guesstimate that well under 20% of beekeepers actively rear their own queens, despite the obvious benefits ... to say nothing of the emotional rollercoaster and eventual satisfaction it brings).

Something major, like a herd of cows stampeding through your apiary, knocking over the cell raiser and destroying both the developing cells and the colony, feels like a punch to the solar plexus ... you may not be able to try again that season, and you may never try again.

In my early, faltering, cack-handed fumblings at queen rearing I fretted about almost every single manipulation.

By trying too hard to get things right, I got things wrong.

I was really careful with my grafting, so took too long, resulting in the larvae drying out (or overheating, they rarely chill).

I'd grafted a dozen and got just two or three cells.

I was down, but not out.

And, although my subsequent handling of the cells was also faltering, cack-handed and fumbling, I still got a couple of queens mated ... and it felt amazing.

Will she? Won't she?

Will she emerge, mature and go on a few orientation flights, successfully embark on - and return from - several mating flights, only meet drones with good genes, avoid the swooping swallows and swifts, and finally settle back in the hive and lay hundreds of thousands of eggs for the rest of her life?

That's a lot of things to go wrong.

For a beekeeper, particularly the first time or two you have a dabble at queen rearing, that's a lot to worry about.

If you've invested time and thought - and perhaps even your meagre profits from honey sales - into getting to the stage of having ripe, capped queen cells, you do not want to stumble at the last hurdle and fail to get those queens mated.

Each is an opportunity for disaster ... or triumph.

But you have even less control over this part of the process than you did producing the cells in the first place.

Will the weather gods be kind?

It's perhaps notable that weather gods are usually deities associated with hail, lightning, storms and tornadoes ... like Bunzi, the goddess of rain or Umvelinqangi, the god of thunder.

I don't think there are weather gods of benign summer afternoons, with 20°C temperatures, zephyr-like winds and sunshine ... though that's what we'd all like (the beekeeper, the queens and the drones).

This year was the most frustrating summer I've experienced queen rearing. Cells a'plenty, but could I get the queens well-enough mated that the colony didn't try and supersede her within a week or two?

No, I could not 😢.

At times like this just be grateful for all that useful grafting practice, rather than cursing Bunzi for sending yet another low pressure system barrelling through.

But, to mix my metaphors even worse than normal, there's sometimes a silver lining to those rain clouds; without spending time and effort rearing great slabs of brood, the colony busies itself collecting nectar.

I think it's no coincidence that it was my worst summer ever for queen rearing, but my best ever summer honey harvest.

And Hooper is absolutely correct; nothing compares with getting a good crop of honey from a calm, healthy and productive colony headed by a queen you reared.

In tune with nature

To briefly return to Gierach, or more specifically, fly fishing; it's also influenced by the weather, but success is dependent upon good observation and an intimate understanding of the environment and season. What flies should be emerging now, did the cold spring and high water levels last month hold them back?

And beekeeping is like that, 'with knobs on'.

Almost everything is determined by the local environment, the climate and the weather.

By local, I mean within just a few miles.

Not Southern Scotland, but the valley you live in.

The weather report for my part of Scotland might be 'temperatures in the high teens (°C) and mainly dry, with Easterly winds of 5-15 mph', but my local weather 150 metres above sea level, with nothing between me and the Cheviots could be '14°C, squally showers and very windy'.

There's a fundamental difference between those two when it comes to opening colonies. One offers a reasonable chance of completing the necessary hive inspections, the other suggests you'll get wet, won't finish and will have to go back tomorrow.

Understanding how your bees interact with the environment, how the colony develops before it is warm enough for inspections, what they forage on, when they're doing well and when they are struggling, all needs acute observational skill.

Inevitably, whether easily achieved or hard won, one of the most rewarding aspects of beekeeping is being aware of what's going on around you (or at least your colonies) throughout the year.

What's flowering when, is it early or late, are there indications that the entire season is 'slow' or just that particular plant?

Is your apiary in a frost pocket and are things better a mile or two away?

And, just in the same way that our environment changes from day to day and week to week, beekeepers - and bees - are going to have to face the consequences of climate change.

This is going to make beekeeping more difficult.

It's going to bring more disappointment in terms of failed harvests, flooded apiaries and unmated queens.

Of course, a 'glass half full' beekeeper would say it will bring even greater satisfaction when you get a good harvest or well-mated queens.

Climate change is going to result in an increased awareness of the impact of honey bees - an introduced species, and one usually present at artificially high levels, in much of their range - on the other species with which they share the environment. I've been reading and thinking about this aspect of beekeeping a lot more and expect it to become a major issue in the future.

And those discussions are going to involve a completely new set of emotions ...

Honest , hard work

I've spent my career moving little test tubes or Petri dishes about, writing stuff on bits of paper or sitting behind a computer writing yet more stuff. In between all that I've done a lot of talking.

Some of this might be considered difficult, and a bit required careful thought, but none of it brought the bone-aching weariness of hard, physical work that beekeeping can.

Has anyone studied the benefits of beekeeping in terms of physical fitness?

A half day in the apiary in high summer, with the sun beating down, with colonies to split, queens to distribute, supers to shift and hives to inspect, can be both exhausting and exhilarating.

Perhaps it's the endorphins?

The honey harvest is the same. Hard, physical work, repetitive, sometimes noisy, always sticky, interspersed by cups of tea as an excuse to tally up the cumulative weight of honey extracted so far.

After a day or two of that it feels great to shower and then slump contentedly in a comfy chair with a well-earned beer.

You can feel pleased with the season. You've earned it.

But, if you do a search for 'honey extraction' you're much more likely to find a comparison of uncapping knives, or a review of a radial extractor, than an account of the heat and noise and amazing smell of the extraction room ... the wax, the propolis and bucket after bucket of sparkling, golden honey.

Again there are highs and lows, like discovering that the first super extracted has a water content of 15% 😄 or forgetting to close the extractor gate, and watching a large puddle of lime honey spread across the floor 😢.

Oh how we laughed!

There's more to beekeeping than keeping bees.

If you're a beginner, you've got a lot to look forward to.

If you've been doing it for years, you know all this already.

"Life is short and responsibility overrated", John Gierach 1946-2024

Sponsor The Apiarist

The Apiarist covers 'the science, art and practice of sustainable beekeeping ... so much more than honey' and I write it to assuage my guilt about culling unsuitable queens or 'shaking out' colonies of laying workers.

If you found this post provocative, useful or amusing, or encouraged you to try fly-fishing or Gierach's writing, then please consider sponsoring The Apiarist.

Sponsorship costs less than £1/week annually, or currently little more than a large cappuccino monthly. Sponsors help ensure the weekly posts appear, receive an irregular (approximately monthly) newsletter, and have access to an increasing number of sponsor-only content ... those starred ⭐ in the lists of posts.

Alternatively, you can help reduce my caffeine overdraft ... and please spread the word to encourage others to subscribe.

Thank you.

{{1}}: The latter a Brit.

{{2}}: 'Fly fishing small streams' and 'Fly fishing the High Country'; both are really collections of short stories craftily disguised as 'How to ... ' guides.

{{3}}: And many tales have their origins in the mid/late 80's in Midwest America.

{{4}}: I've been a fly fisherman much longer than I've kept bees.

{{5}}: Despite the fact that many fly fishers always practice 'catch and release'; as Lee Wulff said "Game fish are too valuable to be caught only once."

{{6}}: Though perhaps not in a nuc.

{{7}}: Even if the rod is constructed from woven carbon fibre, lovingly glued together with a mix of unobtainium and unicorn tears ... and priced accordingly.

{{8}}: Though I may not be visiting the right bookshops, or reading the right websites.

{{9}}: And I don't mean in the mail.

{{10}}: A lot more in my case, as the 'catching' bit is unusual, rather than the norm.

{{11}}: Though the implied force or fury implied by maelstrom is notably absent ... the bees are replete with honey and unlikely to pick a fight.

{{12}}: Don't count your chickens before they hatch ... those queens have still got to get mated!

Join the discussion ...