Under pressure - the Speidel Hydropress

As a beekeeper, if you have lived in different areas of the country, you will be aware of the profound impact the local forage and climate have on your bees. Of course, in a single location these can vary from season to season. However if you move from the fertile agricultural lowlands to a mountainous region, or from South to North or vice versa, then everything changes. The length of the season is probably different, the spring and summer nectar flows may well occur in different months and can be from completely different sources.

I started beekeeping in the UK Midlands; rich farmland interspersed with copses and mixed woodland. The bees got a flying start on the oil seed rape (OSR) in April and, in good years, the summer honey was followed by late season balsam and ivy. Even if I didn’t extract it, I saved a lot of expense on fondant for the winter.

I moved to the East coast of Scotland (and still keep bees there). Spring is later, but it is still rich arable farmland with ample OSR, though not until May. Autumns are cooler and only very rarely do the bees get anything from the ivy. The summer honey is taken off in early/mid-August and that’s the end of the season.

But I now live on the remote west coast of Scotland. I doubt there’s any OSR within 50 miles of me. The predominant forage – and the only one that yields well enough for a honey crop – is heather.

And I know almost nothing about the plant, about preparing colonies for heather or extracting the honey.

Actually, that’s not entirely true … I now know a little about extracting heather honey which is what this post is about.

Bell and ling

There are two types of heather of relevance to beekeepers, bell heather (Erica cinerea) and common heather or ling (Calluna vulgaris). There’s a third, the cross-leaved heath (Erica tetralix), but I’m not sure how important it is for the bees or honey.

Bell heather flowers a bit earlier than ling, perhaps from mid-July depending upon the elevation. Around me the ling flowers from early-August to early-September … usually about the same time as the weather changes for the worse and the bees can’t get to it 🙁 .

If you drive up the A9 at the right time of the year the hills north of Dalwhinnie offer a fabulous rolling purple vista of uninterrupted flowering heather. The commercial beekeepers have all the best spots and there are thousands of hives transported to the area every year for the heather.

Beekeepers with lots of heather experience separate the bell and ling harvests and some rate the former more highly. I don’t have the experience, or the benefit of a dependable nectar flow from either.

If you drive along my road you’ll find sporadic patches of purple between the bracken. It’s a poor region for heather. However, on a more positive note, I don’t have to transport anything anywhere as there’s heather on the rough hillside all around the house.

We have bell and ling starting from sometime in mid/late July but not in sufficient quantities to allow me the luxury of doing anything but taking whatever the bees have collected by mid-September.

The best hives might fill two supers, the worst might get one but ignore it altogether.

Inevitably there’s likely to be some blackberry and – in good years – lime mixed in, but it’s predominantly ling … and ling offers some unique problems when it comes to extracting.

Thixotropic

Ling heather is thixotropic which is defined as:

The property of certain gels of becoming fluid when agitated and of reverting back to a gel when left to stand.

Where ‘stand’ could also mean ‘stored in honeycomb’ after collection by the bees.

Why is this a problem?

It’s a problem because honey extraction usually means taking advantage of the fluid nature of honey to spin it out of the comb.

I found a good description of this issue, and of ling honey, in an anonymous article in Nature from 1936:

Ever since Major Hruschka {{1}}, in Venice, discovered in 1865 the principle of honey extraction by the application of centrifugal force, in a rotary extractor, it became no longer necessary to destroy valuable combs in order to separate the honey from the wax. All the native honeys in Great Britain yield to this method of treatment, excepting that derived from the nectar of ling (Calluna vulgaris). Ling honey fails to flow from the combs in an ordinary extractor, and consequently the combs have to be crushed in a press to obtain extraction. Ling honey is rich golden brown in colour and shows a characteristic sparkle due to the presence of minute air bubbles. In the pure form it never granulates but remains as a gelatinous fluid which is more viscous than most other honeys. Its distinctive flavour and aroma also readily distinguish it from other honeys. {{2}}

So, there you have it, ling honey is gel-like and needs to be agitated to make it flow. In 1936 there seemingly weren’t ways to do this in the comb – there are now, see below – so necessitating the crushing of the comb.

Options

I’m not going to discuss preparing cut comb heather honey. It’s not something I have experience of and it’s not something I could dependably achieve as the nectar flow here isn’t usually strong/long enough to get well-filled frames.

And, when it is (like last year), I’ve used wired foundation. D’oh!

Crushing news

In previous years and on a very small scale – a dozen frames or so – I’ve crushed and strained heather honey.

It’s a tediously dull process.

If the frames are unwired you simply cut out the comb, drop it into a bucket and mash it up before straining the honey out through a sieve. It takes a long time and the honey recovery is underwhelming. There always seems to be lots left associated with the crushed comb.

If the frames are wired you can add scraping back the comb to the midrib and/or extracting the wires to the process described above.

Frankly none of that is my idea of fun.

Getting agitated

Since that 1936 article appeared there are now ‘heather looseners’. These have a row of blunt needles which you push through the cappings, effectively agitating the honey ready for extraction.

Thorne’s do a manual one for £100. Abelo sell a semi-automated one from Lyson for £5,270.

The Thorne’s loosener does 196 cells at a time. There are ~2000 cells per side on a National super frame.

Perhaps you are starting to appreciate the tedium of the task ahead?

Alternatively, for five grand, you can automate it … partially.

The Lyson loosener does one frame at a time.

Yikes.

I know there are alternatives to the two looseners I’ve listed. I’ve no experience of any of them so cannot comment on their good or bad points … other than I’d prefer not to have yet more equipment to clean after extracting.

Semi-automated crushing

So, it’s back to crushing and straining.

Most of the beekeeping suppliers sell fruit presses of one type of another. These have a metal cage into which you add a muslin (or similar) bag containing honey in the comb. The honey is squeezed out either using a hand-turned press, or a ‘car jack’-type pneumatic press.

I’ve not used any of these. When I’ve discussed them with other beekeepers the comments are often not encouraging; “very hard work”, “small scale and low volume” or “poorly designed”.

I looked at one press selling for £270. Although it was stainless steel (and don’t consider one that isn’t) it was poorly finished, with crude welding on the legs, frame and handle.

It is a bit more automated than manually crushing the comb, but not much.

However, there are larger fruit presses that are more automated. These include the Speidel Hydropress which I know others have used for honey extraction.

Having discussed this machine with ‘regular reader’ Elaine, who purchased one for her association and kindly sent me videos of it in action, I bought one from Vigo Presses.

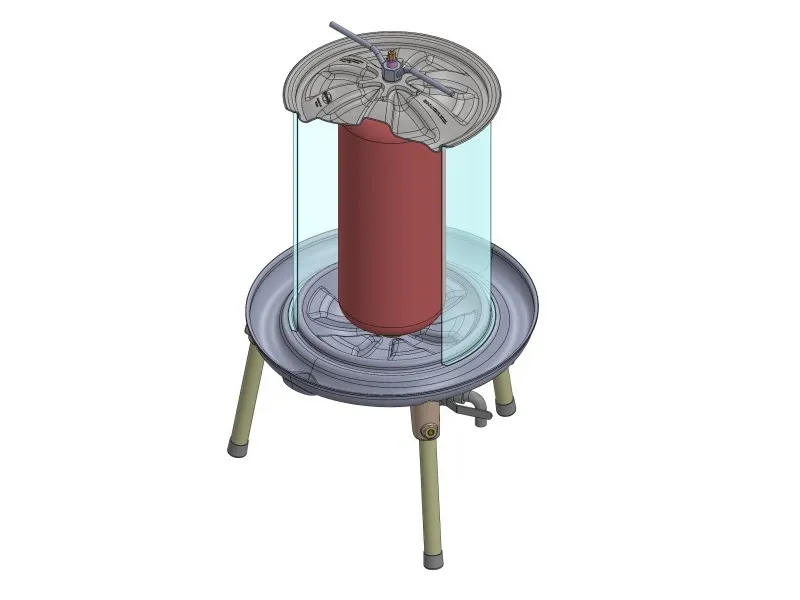

The Speidel Hydropress

Speidel are a German manufacturer of a wide range of equipment used for apple juice and cider preparation.

The press consists of a perforated stainless steel basket that stands on a circular concave drain. There is a hefty lid secured with a large hand-turned screw.

The clever bits are all inside.

In the centre is a rubber bladder topped with a manual pressure release valve that protrudes through the heavy metal lid.

Underneath are a pressure gauge, an automated pressure release valve and the inlet and outlet ports, which have separate taps.

The entire thing sits on three stout legs, one of which is longer than the others to ensure everything runs towards the the drain at the ‘front’ of the machine (and not over the pressure valve and inlet/outlets which are on one side).

As might be expected from a German manufacturer, the machining and finish are excellent.

I purchased the 40 litre press which, with a spare filter bag, cost about £860 including shipping to the howling wilderness.

Low pressure

As the name implies, the Hydropress is water-powered. You ‘inflate’ the bladder by attaching the press to a hose from a standard domestic water supply. The input pressure must not exceed 3 bar.

Unfortunately we don’t have a standard domestic water supply.

We have a burn (small stream). The water comes from this via a kilometre or so of pipe to a tank above the house. Our water pressure is well below 1 bar, insufficient to power the Hydropress.

I knew this when I purchased it and already had a cunning plan. Unlike Baldrick’s cunning plans, mine wasn’t ridiculed …

… and it worked.

I filled a large dustbin with water and used it as the reservoir for a 3 bar electric pump. I ran the outlet from the Hydropress back into the dustbin. All this had to be outdoors (the pump leaks a bit), so I purchased a 25 m reinforced hose to connect everything together.

This type of pump overheats if left ‘on’ against a closed tap. I therefore rigged up a WiFi-connected on/off switch so I could control it from my phone as I attended to the Hydropress.

This all worked remarkably well.

Setup

You need access to the top of the press to fill it. When it is in use you need to be able to see the gauge and easily operate the inlet and outlet taps. Once filled it is too heavy to move.

You therefore need a low sturdy table for the press. I used a Black and Decker Workmate with a large, strong, flat piece of wood clamped on top. I used a ‘step stool’ when loading the machine.

If that all sounds a bit precarious, it isn’t. With care the uncapping (see below), loading and extracting made considerably less mess than with my standard radial extractor.

As with any honey extraction, you will need easy access to a sink, hot water and about 9,000 miles of disposable kitchen towels.

The Hydropress legs are sufficiently long to raise the ‘drain’ above a 15 kg honey bucket, but there’s not a lot of space to spare. If you want to filter directly you’ll need to use some ingenuity.

Filling the press

The perforated cage of the press is lined with an open-ended – relatively coarse – filter sack, folded under (i.e. towards the centre) the base of the bladder. The top of the sack is initially folded out over the upper edge of the cage.

I used a Smith cutter/scraper to scrape the honey comb back to the central rib over a bucket. There’s a definite technique to doing this well … and it’s not one I have.

I trashed quite a few frames in the process.

Nothing ventured, nothing gained.

Next year I’ll either use thin unwired foundation and just cut it out and dump it directly into the press, or plastic foundation and the Smith cutter.

I didn’t bother breaking up the comb. The few unwired frames were just cut into three big lumps and dropped in.

Take care not to add any wooden splinters or pieces of wire into the press. If you perforate the bladder the honey will be ruined. When full, the value of the honey might exceed the cost of the press.

Don’t say I didn’t warn you.

Extracting the honey

Once full (see the conclusions) you fold the upper edge of the filter bag inwards, covering the contents, securely attach the lid and then shut off the outlet.

The taps are labelled on/off, but the writing is tricky to read underneath the press. Make sure you know which way they both operate as you might need to used them in a hurry.

Once the water supply is turned on the bladder starts to fill. Since it is already full of air, this must be released to allow more water in. This is what the small release valve on the top of the stem is used for.

The air hisses out. As soon as any water appears take your finger off the valve to close it. The upper surface of the lid is recessed so can accommodate a dribble of water without it running down the side of the machine.

Why is that important?

Because the honey is already weeping out through the metal cage, running down to the drain and then into the bucket.

Do not let any water mix with the honey!

In addition, make sure you have a honey bucket under the drain as you load the machine.

Slow and steady

It’s then ‘simply’ a case of controlling the water pressure of the inlet to determine the flow of honey coming out. If you turn up the pressure too much you rapidly overflow the drain, covering the tabletop, your legs, shoes and the floor with kilograms of honey.

How do I know?

I have a good imagination.

Run the press slowly. Initially the honey comes out fast {{3}} as the pressure is slowly ramped up. Towards the end of the run – the only time you really need a full 3 bar of pressure – the honey is only seeping out slowly.

All this involves fine control of the pump – on/off/on/off etc. – and/or of the inlet valve.

If you exceed 3 bar the automatic valve under the machine releases water … make sure you have a small bowl ready to catch any dribbles.

Swap honey buckets as needed. You can slide the filled one underneath the machine as you introduce the new one, spilling no honey during the transition.

Setup and loading the machine took me about 3-4 hours. The run took well under half that time.

I worked alone and had to sort out the pump, struggle with the Smith cutter and deal with the worry of using a high pressure water supply in close proximity to about a grand of honey.

Now I know what I’m doing it will be faster next time.

Cleaning up

Inevitably this is the worst part of the entire process. Once the run is ended you turn off the pump and drain the bladder via the outlet.

When you remove the lid you’re faced with a relatively dry cake of wax stuck pretty firmly to the inner face of the mesh bag.

Roll your sleeves up and carefully pull it all out. This is good (but not great) wax so is valuable. Dump the wax in a bucket, remove and soak the mesh bag and clean the extractor.

I used a hose and lots of hot water. It’s not easily an indoor task. The extractor has a few nooks and crannies below the bladder in which honey gets trapped.

In late summer I’d do this outdoors late in the evening to avoid the attention of lots of bees. Funnily enough, this wasn’t an issue in early January.

Like everything associated with beekeeping the press takes up quite a bit of room. It’s a metre high and over 50 cm in diameter. I’m looking for a suitable storage bag for it.

Conclusions

I’ll write a more detailed account of using the machine at some point in the future.

I extracted 40 kg of honey from a single run. I overfilled the machine slightly and had some leakage out from under the lid. This just runs down the outer wall of the cage so isn’t a (messy) problem.

I pre-warmed my supers at ~38°C for several days over my honey warming cabinet to help extraction. I don’t know whether it did or not, but the room smelled fantastic. The extracted honey had a water content of 16%, pretty good for heather.

I ended up with a few un-extracted frames because, a) they wouldn’t fit, b) it wasn’t worth doing a second run with a fraction of a full load, and c) I’m not very observant and missed an entire part-filled super. D’oh!

I gave them to friends and family.

For my scale of heather production (small to middling non-existent to small) which is unlikely to exceed ~75 kg a year this 40 litre machine worked well. If you produce more it might not be suitable (and you’ll already have a solution).

It should be possible to do two sequential runs in an afternoon, particularly if you use a fresh mesh bag for the second run.

The water gave me some sleepless nights.

However, I had talked to suppliers about similar machines powered by compressed air and there were clearly some major technical issues with them. Some have stopped importing or selling them.

As it turned out the water wasn’t an issue at all.

If you ignore the costs of the jars, lids, labels, hose, fittings {{4}}, Smith cutter and my time, the machine just about paid for itself in a single run.

Thanks

Vigo Presses were excellent to deal with. They shipped quickly and sent me a replacement machine when the first had a minor manufacturing fault to one of the legs. There were no quibbles and the new machine was shipped before the first was collected.

Finally, thanks again to Elaine who showed me their machine in action and who answered my interminable half-baked and nonsensical questions.

Note

If only some of the images display in your browser it might be because it needs updating. I’m switching to a different image format (WEBP) which are smaller and therefore load faster. All modern mainstream browsers – Chrome, Safari, Firefox (which together make up 99% of those used by visitors here) – offer a version for phones, tablets and desktops that supports this image format, usually since about 2020.

{{1}}: Franz Hruschka

{{2}}: Physical Properties of Heather Honey (1936) Nature 138: 770–770 https://www.nature.com/articles/138770a0.

{{3}}: Fast is relative, remember it’s viscous heather honey.

{{4}}: Buy brass, not rubbish plastic.

Join the discussion ...