Bait hives, evolution & compromise

I gave a talk on bait hives to a friendly group of beekeepers from Westerham last week. Westerham is near Sevenoaks in Kent, a rich agricultural area with lots of fruit growing and hops for the brewing industry.

And, as you will see shortly, lots of beekeeping.

One of the messages I try and get across in my talk on bait hives is that it is a remarkably successful way to capture swarms … and a whole lot less work than teetering precariously on a step ladder holding a skep.

However, success involves two things:

- understanding the needs of the swarm, and

- overcoming the doubt that such a passive activity – essentially putting a box in a field – can be so successful.

But I’m getting ahead of myself.

Some readers may not know what a bait hive is.

The post this week is not intended to be a comprehensive account of how you should prepare and set out bait hives. I’ve covered this topic ad nauseam before. Instead, I’m going to try and convince you that, although it is a passive activity, if you do things correctly you are very likely to succeed.

And then, in the second half of the post, I’ll discuss an interesting question (and my – possibly less interesting – answer) from one of the Westerham beekeepers that is a nice illustration of some of the compromises that beekeeping entails.

Bait hives and swarm traps

A bait hive is an artificial nest site placed somewhere suitable to attract a swarm.

In the US these are often called ‘swarm traps’.

I don’t think either name is perfect … a bait hive doesn’t involve ‘bait’ {{1}} and a swarm trap doesn’t really ‘trap’ the swarm as they are free to leave again.

That they (almost) never do is rather telling … I touch on this in my post on absconding.

Perhaps the term ‘swarm hive’ would be better? {{2}}

A bait hive possesses the features that scout bees look for when searching the environment for a new nest site. Essentially these are the following:

- a 40 litre void

- smelling of bees

- with a small entrance situated near the bottom of the void

- facing south

- shaded but clearly visible

- and located at least 5 metres above the ground

The majority of these features were defined by studies of natural swarms and in experiments by Thomas Seeley described in his book Honeybee Democracy {{3}}.

Conveniently a beekeeper can meet these needs by assembling the following and placing it somewhere suitable:

- a brood box with a roof, a solid floor and a small entrance

- filled (completely or partially) with foundationless frames plus one old dark brood frame

- a drop or two of lemongrass oil

Surely it can’t be that easy?

Yes it can … and it is.

But let’s first try and overcome the impression that something as simple and passive as a box in a field will even be found by scout bees, let alone selected by them as the new nest site for the swarm.

If you build it, they will come

In the 1989 file Field of Dreams an Iowan farmer, Ray Kinsella (played by Kevin Costner), follows his dream of creating a baseball field in his corn field. The oft misquoted ’If you build it, they will come’ from the movie really means that if you put your doubts aside you will succeed {{4}}.

He cuts down his corn, builds a baseball field and Shoeless Joe Jackson and the banned 1919 Chicago White Sox players appear.

Kinsella was attracting disgraced baseball players from 50 years earlier … all your bait hive needs to do is attract a swarm from a nearby mismanaged {{5}} hive.

Which is a whole lot easier.

Nearby hives

So how many nearby hives are there? How many are likely to swarm? And how near is nearby?

Let’s return to the lovely blossom-filled orchards around Westerham in Kent for some specifics.

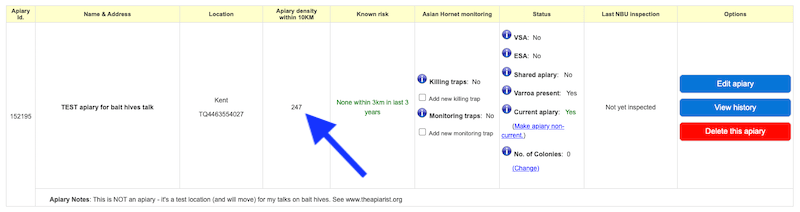

The National Bee Unit’s Beebase has information on the number of apiaries within 10 km of any of your own apiaries that are registered.

You are registered, aren’t you? {{6}}

Within a 10 km radius of Westerham there are 247 other apiaries. That’s a lot {{7}}, but I’ve no doubt it reflects the excellent forage in the area, and the unstinting efforts of Kent beekeeping associations to train more beekeepers.

How many hives do these apiaries contain? I have to start guessing here as mere mortals can’t mine that sort of information from Beebase.

Let’s assume five hives per apiary.

That seems a reasonable number to me {{8}}.

Firstly, it’s a sensible minimum number of hives to co-locate in an apiary. Secondly, with about 250,000 managed colonies in the UK and about 50,000 beekeepers, if we assume that they are evenly distributed {{9}} it works out as a rather neat 5 hives per apiary.

Which means that in the 314 square kilometres within a 10 km radius of Westerham there are over 1200 hives, which equates to almost 4 hives per square kilometre (the precise number is 3.931, but you’ll appreciate I’m in arm waving mode here).

How far do scout bees, er, scout?

To answer this we can safely (but briefly) disengage arm waving mode.

Scout bees fly from and return to the bivouacked swarm. They then communicate with other scout bees by performing a waggle dance on the surface of the bivouac.

Thanks to Karl von Frisch we can decipher the waggle dance, which includes both directional and distance information.

And from doing exactly that we know that scout bees survey the landscape for at least 3 km from the swarm.

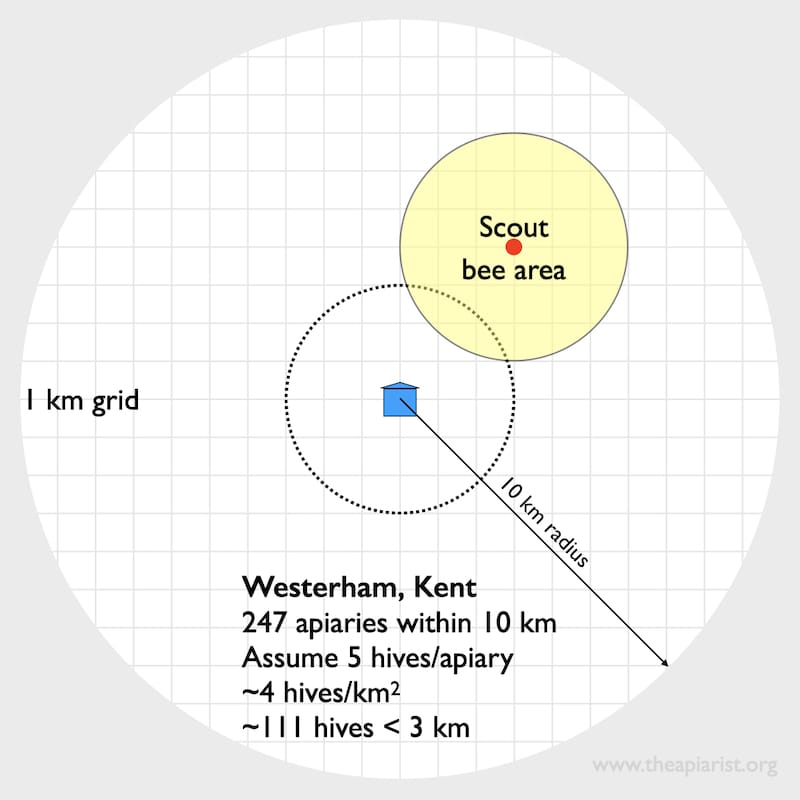

In the diagram above a typical area investigated by scout bees is indicated by the pale yellow circle. The red dot indicates the bivouacked swarm. The grid in the background is 1 km squares.

The bait hive is in blue in the centre of a circle of radius 10 km. The smaller dotted circle represents the maximum distance from which a scout bee would travel to find the bait hive {{10}} .

Let’s put some numbers on that.

Assuming the average hive density at Westerham is about 4 per km2 and that apiaries and hives are evenly distributed, there will be 111 hives within the smaller dotted circle of radius 3 km {{11}} .

If any of those hives swarm, their scout bees could or should find the bait hive.

And, if they like the bait hive enough, they might persuade their fellow scouts to check it out and – in due course – together lead the swarm to the bait hive.

The final piece of the jigsaw necessitates re-engaging arm waving mode …

Ready?

What proportion of hives swarm each year?

Over the last several years I would say that the majority of my full-sized production colonies have tried to swarm each season. By ’tried’ I mean produced charged queen cells which necessitated me employing swarm control.

The vast majority of these colonies did not swarm … because the swarm control was successful.

But I’ve certainly lost a few swarms over the years 🙁

About 80% of free-living colonies studied by Thomas Seeley in the Arnott Forest swarmed each season. There are reasons to think that this may be higher than normal {{12}}, but possibly not much higher than large, healthy managed colonies.

So, if 80% of managed colonies around Westerham ‘try’ and swarm each season, the actual number of swarms is a reflection of how well trained the beekeepers of Kent are … and, for those who have kept bees for several seasons, how effective they are at swarm control.

And, whilst I’m sure the training is excellent and the swarm control is diligently applied, I’m equally sure that many swarms are lost 😉

If we assume that only 10% of colonies swarm, that’s still 11 swarms a season within range of a bait hive placed anywhere within the larger 10 km radius circle.

And I’d wager my favourite hive tool {{13}} that it’s more than 10% 😉

Evolution of nest site preferences

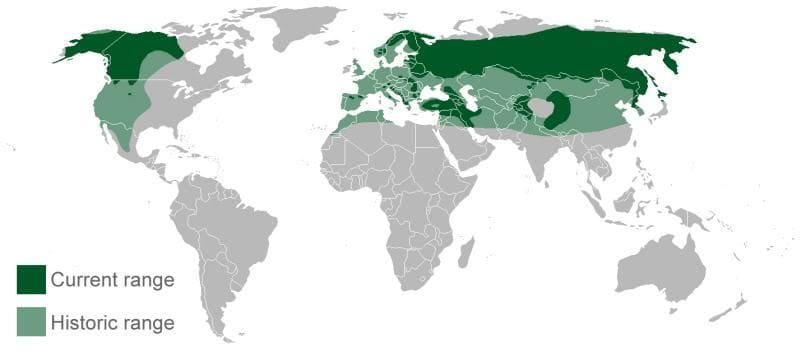

The preferences shown by scout bees {{14}} have evolved because swarms that move into nest sites like these survive better.

If they survive, they are also more likely to reproduce (swarm), so passing on the genes that were instrumental in creating the bees that selected those particular features in a nest site.

This does not mean that the nest site features are absolutes.

For example, a 35 litre or 45 litre void is likely to be just as attractive.

In fact, the scout bees may not be able to discriminate between these anyway.

However, although a tiny 10 litre void or a cavernous 100 litre space is less attractive, it does not mean that a swarm won’t select a cavity of these volumes and move in.

Whether it does or not depends upon what other choices are available and upon the poorly understood (at least by me) ranking of the importance of the various features of the nest sites.

For example, if you offer a poxy {{15}} 10 litre bait hive in an environment rich in suitable 40 litre cavities you will probably be unlucky.

However, if the bees rank void volume as relatively unimportant, and your bait hive was perfect in all other regards, then perhaps they would choose to move in.

Compromises by bees

In reality, they probably would not move in to a 10 litre bijou bait hive, perfect in all other regards, as the volume available is the primary determinant of how big the colony can get, how much brood it can rear and how much pollen and nectar it can store.

Furthermore, the natural environment (in which I include your bait hive placed in the landscape) does not offer simple choices in which only individual features vary.

Almost everything varies … even two apparently similar bait hives are likely to occupy locations with more or less exposure, or greater or lesser shade, between which the scout bees will choose.

And natural cavities, in trees, church towers or compost bins {{16}} are likely to vary in many or all of the features judged by scout bees.

The scout bees make their decision based upon the sum of the overall desirability of a nest site, which is undoubtedly influenced by their ranking of which features are more or less important.

Perhaps they can cope with a west facing entrance that’s a bit larger than they would prefer if the shade is good, the space is the right size and it pongs nicely of bees.

It’s effectively a compromise.

But remember that your bait hive has to compete with the wealth (at least in some landscapes) of natural nest sites.

In this regard, you have an advantage. The more of the desirable features you offer, the more desirable the nest site should be.

Q&A

Which, by a typically long and circuitous route, brings me to the interesting question from a Westerham beekeeper {{17}} following my bait hive talk:

If scout bees prefer bait hives with solid floors does this mean that bees prefer solid floors over open mesh floors?

I can’t remember the exact wording of my answer but know it involved reference to the draughtiness of the space. I hope I also mentioned the amount of light inside the void, but can’t be sure.

A more complete answer would be that bees aren’t too worried about a draughty space, at least one with small holes, cracks or fissures, as these can be filled with propolis. However, they do prefer a dark space, and a bait hive with an open mesh floor would presumably be too well illuminated for the scout bees.

I think this reflects the evolution of nest site choice.

Bees have evolved to prefer (select) dark spaces as these – by definition – don’t have large holes that let light or more importantly bears, honey badgers and robbing bees, in.

Natural cavities don’t have mesh floors. Indeed, stainless steel mesh isn’t something that bees will have experienced for the first few million years of their evolution.

Therefore, it’s not that they prefer solid floors over mesh floors, it’s that they prefer dark, secure spaces over well lit voids that may well be difficult to defend.

But, when setting out your bait hives there’s an easy fix … simply cover an open mesh floor with a piece of cardboard or Correx. You can always remove it again once the bees have arrived.

What do the bees want?

But do scout bee preferences tell us something about what the colony, once established, prefers?

Not necessarily, at least with regard to the closed or open nature of the floor.

Let’s accept that that scout bees (and therefore swarms) prefer a solid floor for the reasons given above. That is not the same as it being an indication that the established colony would prefer a solid floor over an open mesh floor.

If they did, what differences in the behaviour of the bees would you observe?

- I think you’d see more colonies absconding from hives with open mesh floors than those with solid floors. I’m not aware of any data showing that colonies on solid floors abscond less. I don’t use solid floors and have never had a full colony abscond.

- The bees would cover and seal the mesh with propolis. Again, I’ve never seen this in my own hives, though I regularly see them blocking gaps over the colony with propolis.

There are enough beekeepers still using solid floors, and even some reverting from mesh floors to solid floors. However, I don’t think I’ve ever heard a beekeeper moving (or moving back) to solid floors to reduce the number of colonies that abscond.

Have you?

Compromises by beekeepers

Finally, let’s return to that list of desirable features sought by the scout bees.

Remember that they are not absolute.

Just because a bait hive faces west doesn’t mean it will be ignored by scout bees. I’ve attracted two swarms in successive days to one west facing bait hive in my garden. The same bait hive caught a swarm two months earlier as well {{18}}.

By facing the bait hive west I got a better view of the entrance … it was a compromise that suited me.

Under offer …

I regularly use two stacked supers (in place of a brood box) as a bait hive. These have been very effective, despite having about 25% greater volume {{19}}.

Again, this is a compromise that suits me. It allows me to use some supers that I dislike because they have an overhang/rebate and are infuriatingly incompatible with my other equipment.

I also never site bait hives more than 5 metres above the ground.

In fact, I almost always site them at knee height.

Bees have probably evolved to choose high altitude nest sites to avoid predation by bears.

There are no bears in Scotland, at least not wild ones, though historically they were present. Their absence isn’t why I don’t bother to place my bait hives up trees.

I want to be able to observe scout bee activity easily. More importantly, I want to be able to safely move the hive late in the evening of the day the swarm arrives.

I can do both these things much better with the hive on a hive stand.

It probably makes the bait hives slightly less attractive to the scout bees, but it’s a compromise I’m willing to make as it improves my enjoyment of the bees and simplifies my beekeeping.

If I wanted to climb ladders I’d go out collecting bivouacked swarms in a skep 😉

{{1}}: At least not in the conventional sense of the word. Let’s not get distracted by pedantry so early in the post.

{{2}}: OK, forget it!

{{3}}: And by others, but that book is an excellent guide to the subject.

{{4}}: The actual quote from Field of Dreams was “If you build it, he will come” … the ‘he’ in the film means various long-dead baseball players and Kinsella’s father.

{{5}}: Because otherwise they’d have used swarm prevention and control and there would be no swarm.

{{6}}: If not, you should.

{{7}}: For comparison, my apiaries in Fife have about 50 other apiaries within 10 km.

{{8}}: And not just because I thought of it.

{{9}}: They’re not.

{{10}}: So scout bees from a swarm at the red dot would not find this bait hive.

{{11}}: And, by extrapolation, any bait hive within the 314 km2 should be within range of ~111 potentially swarmy colonies.

{{12}}: Due to the behavioural changes that have evolved in response to high Varroa loads carried by feral colonies.

{{13}}: The one engraved with the words ”Dummkopf … knocking back queen cells is not swarm control.”

{{14}}: Which, if you’ve forgotten are a 40 litre void, smelling of bees, with a small entrance situated near the bottom of the void, facing south, shaded but clearly visible and located at least 5 metres above the ground.

{{15}}: Meaning rotten or lousy, rather than suffering from pox.

{{16}}: Perhaps the last two don’t qualify as natural but I was really meaning not placed there by a beekeeper.

{{17}}: Whose name I’m afraid I missed. Anyway, Zoom screens don’t always display meaningful names for attendees, and the beekeeper probably wasn’t named iPad2 or Office PC.

{{18}}: And was successful every year it was placed there.

{{19}}: Seeley didn’t test the desirability of bait hives that differed by just a few litres. In Honeybee Democracy he states that bees ’… avoid cavities smaller than 10 litres or greater than 100 litres, and that they very much like 40 litre cavities …’ .

Join the discussion ...