Quick thinking & second thoughts

I gave my last talk of the winter season on Tuesday to a lovely group at Chalfont Beekeepers Society. The talk {{1}} was all about nest site selection and how we can exploit it when setting out bait hives to capture swarms.

It’s an enjoyable talk {{2}} as it includes a mix of science, DIY and practical beekeeping.

Nest sites, bait hives and evolution

The science would be familiar to anyone who has read Honeybee Democracy by Thomas Seeley. This describes his studies of the features considered important by the scout bees in their search for a new nest site {{3}}.

The most important of these are:

- a 40 litre cavity (shape unimportant)

- a small entrance of 10-15cm2

- south facing

- shaded but in full view

- over 5m above ground level

- smelling of bees

All of which can easily be replicated using a National brood box with a solid floor. Or two stacked supers.

And – before you ask – a spare nuc box is too small to be optimal.

That doesn’t mean it won’t work as a bait hive, just that it won’t work as well as one with a volume of 40 litres {{4}}.

Evolution has shaped the nest site selection process of honey bees. They have evolved to preferentially occupy cavities of about 40 litres.

Presumably, colonies choosing to occupy a smaller space (or those that didn’t choose a larger space {{5}} ) were restricted in the amount of brood they could raise, the consequent strength of the colony and the weight of stores they could lay down for the winter.

Get these things wrong and it doesn’t end well 🙁

A swarm occupying a nuc box-sized cavity would either outgrow it before the end of the season, potentially triggering another round of swarming, or fail to store sufficient honey.

Or both.

Over thousands of colonies and thousands of years, swarms from colonies with genetics that chose smaller cavities would tend to do less well. In good years they might do OK, but in bad winters they would inevitably perish.

Bait hive compromises

If you set out a nuc box as a bait hive, you’re probably not intending to leave the swarm in that box.

But the bees don’t know that. Their choices have been crafted over millenia to give them the best chance of survival.

All other things being equal they are less likely to occupy a nuc box than a National brood box.

For this reason I don’t use nuc boxes as bait hives.

However, I don’t recapitulate all the features the scout bees look for in a ‘des res’.

I studiously ignore the fact that bees prefer to occupy nest sites that are more than 5 metres above ground level.

This is a pragmatic compromise I’m prepared to make for reasons of convenience, safety and enjoyment.

Bees have probably evolved to favour nest sites more than 5 metres above ground level to avoid attention from bears. The fact that there are no bears in Britain, and haven’t been since the Middle Ages {{6}}, is irrelevant.

The preference for high altitude nest sites was ‘baked into’ the genetics of honey bees over the millenia before we hunted bears {{7}} to extinction.

However, I ignore it for the following reasons:

- convenience – I usually move occupied bait hives within 48 hours of a swarm arriving. It’s easier to do this from a knee height hive stand than from a roof ladder.

- safety – I often move the bait hive late in the evening. Rather than risk disturbing a virgin queen on her mating or orientation flights (assuming it’s a cast that has occupied the bait hive) I move them late in the day. In the ‘bad old days’ when I often didn’t return from the office until late, this was sometimes in the semi-dark. Easy and safe to do at knee height … appreciably less so at the top of a ladder.

- enjoyment – I can see the scout bees going about their business at a hive near ground level without having to get the binoculars out. Their behaviour is fascinating. If you’ve not watched them I thoroughly recommend it.

Scout bee activity

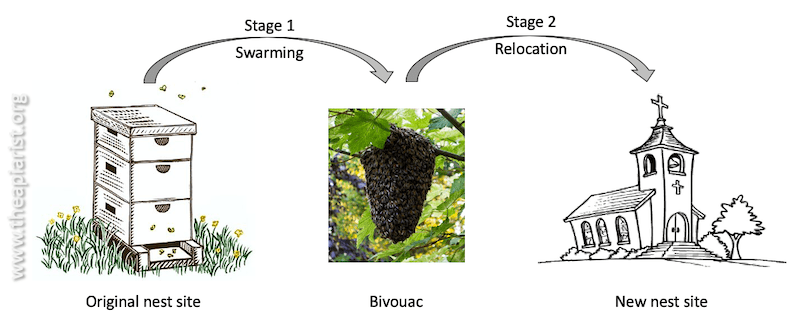

The swarming of honey bees is a biphasic process. In the first phase the colony swarms and forms a temporary bivouac nearby to the original nest site.

The scout bees search an area ~25 km2 around the bivouacked swarm for suitable nest sites. They communicate the quality and location of new nest sites by performing a waggle dance on the surface of the bivouac.

Once sufficient scouts have been convinced of the suitability of one of the identified nest sites the second phase of swarming – the relocation of the swarm – takes place.

However, logic dictates that the scout bees are likely to have already identified several potential new nest sites, even before the colony swarms and clusters in a bivouac.

There are only a few hundred scout bees in the swarmed colony, perhaps 2-3% of the swarm.

Could just a few hundred scouts both survey the area and reach a quorum decision on the best location within a reasonable length of time?

What’s a reasonable length of time?

The bivouacked swarm contains a significant amount of honey stores (40% by weight) but does not forage. It’s also exposed to the elements. If finding sites and reaching a decision on the best nest site isn’t completed within a few days the swarm may perish.

Which is why I think that scout bees are active well before the colony actually swarms.

Early warning systems

If scout bees are active before a colony swarms they could be expected to find and scrutinize my bait hive(s).

If I see them doing this I’m forewarned that a colony within ~3 km (the radius over which scout bees operate) is potentially making swarm preparations.

Since I’ll always have a bait hive or two within 3 km of my own apiaries I’ll check these hives at the earliest opportunity, looking for recently started queen cells.

Whether they’re my colonies or not, it’s always worth knowing that swarming activity has started. Within a particular geographic area, with similar weather and forage, there’s usually a distinct swarming period.

If it’s not one of my colonies then it soon might be 😉

So, in addition to just having the enjoyment of watching the scout bees at work, a clearly visible – ground level – bait hive provides a useful early warning system that swarming activity has, or soon will, start.

Questions and answers

Although talking about swarms and bait hives is enjoyable, as I’ve written before, the part of the talk I enjoy the most is the question and answer session.

And Tuesday was no exception.

I explained previously that the Q&A sessions are enjoyable and helpful:

Enjoyable, because I’m directly answering a question that was presumably asked because someone wanted or needed to know the answer {{8}}.

Helpful, because over time these will drive the evolution of the talk so that it better explains things for more of the audience.

Actually, there’s another reason in addition to these … it’s a challenge.

It’s fun to be ‘put on the spot’ and have to come up with a reasonable answer.

Many questions are rather predictable.

That’s not a criticism. It simply reflects the normal range of topics that the audience either feels comfortable asking about, or are interested in. Sometimes even a seemingly ‘left field’ question, when re-phrased, is one for which there is a standard answer. The skill in this instance is deciphering the question and doing the re-phrasing.

But sometimes there are questions that make you think afresh about a topic, or they force you to think about something you’ve never considered before.

And there was one of those on Tuesday which involved biphasic swarming and scout bee activity.

Do all swarms bivouac?

That wasn’t the question, but it’s an abbreviated form of the question.

I think the original wording was something like:

Do all swarms cluster in a bivouac or do some go directly from the original hive/location to the new nest site?

And I didn’t know the answer.

I could have made a trite joke {{9}} about not observing this because my own colonies swarm so infrequently 🙄

I could have simply answered “I don’t know”.

Brutally honest, 100% accurate and unchallengeable {{10}}.

But it’s an interesting question and it deserved better than that.

So, thinking about it, I gave the following answer.

I didn’t know, but thought it would be unlikely. For a swarm to relocate directly from the original nest site the scout bees would need to have already reached a quorum decision on the best location. To do this they would need to have found the new nest site (which wouldn’t be a problem) and then communicate it to other scout bees, so that they could – in turn – find the site. Since this communication involves the waggle dance it would, by definition, occur within the original hive. Lots of foragers will also be waggle dancing about good patches of pollen and nectar so I thought there would be confusion … perhaps they always need to form a bivouac on which the scout bees can dance? Which explains why I think it’s unlikely.

In a Zoom talk you can’t ponder too long before giving an answer or the audience will assume the internet has crashed and they’ll drift off to make tea {{11}}.

You therefore tend to mentally throw together a few relevant facts and assemble a reasonable answer quite quickly.

And then you spend the rest of the week thinking about it in more detail …

Second thoughts

I still don’t know the answer to the question “Do all swarms bivouac?”, but I now realise my answer made some assumptions which might be wrong.

I’ll come to these in a minute, but first let me address the question again with the help of the people who actually did the work.

I’ve briefly looked back through the relevant literature by Seeley and Lindauer and cannot find any mention of swarms relocating without going via a bivouac. I may well have missed something, it wouldn’t be the first time {{12}}.

However, their studies are a little self-selecting and may have overlooked swarms that behaved like this.

Both were primarily interested in the waggle dance and the decision making process, they therefore needed to be able to observe it … most easily this is on the surface of the bivouac.

Martin Lindauer mainly studied colonies that had naturally swarmed, naming them after the location of the bivouac, and then studied the waggle dancing on the surface of the clustered swarm. In contrast, Tom Seeley created swarms by caging the queen and adding thousands of very well fed bees.

Absence of evidence is not evidence of absence.

So, what were the assumptions I made?

There were two and they both relate to confusion between waggle dancing foragers and scout bees.

- Swarming usually occurs during a strong nectar flow. Therefore there are likely to be lots of waggle dancing foragers in the hive at the same time the scouts are trying to persuade each other – using their own fundamentally similar – waggle dances.

- Bees ‘watching’ are unable to distinguish between scouts bees and foragers.

So, what’s wrong with these assumptions?

A noisy, smelly dance floor

Foragers perform the waggle dance on the ‘dance floor’. This is an area of vertical comb near the hive entrance. It’s position is not fixed and can move – further into the hive if the weather is cold, or even out onto a landing board (outside the hive) in very hot weather {{13}}.

So, although the dance floor occupied by foragers isn’t immovable, it is defined. There’s lots of other regions of the comb that scouts could use for their communication i.e. there could be spatial separation between the forager and scout bee waggle dances.

Secondly, foragers provide both directional and olfactory clues about the identity and location of good sources of pollen and nectar. In addition to two alkanes and two alkenes produced by dancing foragers {{14}} they also carry back scents “acquired from the environment at or en route to the floral food source” which are presumed to aid foragers recruited by the waggle dancer to pinpoint the food source.

Importantly, non-dancing returning foragers do not produce these alkanes and alkenes. Perhaps the dancing scouts don’t either?

A dancing scout would also lack specific scents from a food source.

Therefore, at least theoretically, there’s probably a good chance that scout bees could communicate within the hive. Using spatially distant dances and a unique combination of olfactory clues (or their absence) scouts may well be able to recruit other scouts to check likely new nest sites.

All of which would support my view that bait hives provide a useful early warning system for colonies that are in the very earliest stages of swarm preparations … rather than just an indicator that there’s a bivouacked swarm in the vicinity.

But?

All this of course then begs the question … if the scout bees can communicate within the hive, why does the swarm need to bivouac at all?

The bivouac must be a risky stage in the already precarious process of swarming. 80% of wild swarms perish. At the very least it’s subject to the vagaries of the weather. Surely it would be advantageous to stay within the warm, dry hive until a new nest site is identified?

This suggests to me that the bivouac serves additional purposes within the swarming process. A couple of possibilities come to mind:

- the gravity-independent, sun-orientated waggle dancing {{15}} on the surface of the bivouac may be a key part of the decision making process, not possible (for reasons that are unclear to me) within the confines of the hive.

- the bivouac acts to temporally coordinate the swarm. A swarm takes quite a long time to settle at the bivouac. Many bees leave the hive during the excitement of swarming but not all settle in the bivouac. Perhaps it acts as a sorting mechanism to bring together all the bees that are going to relocate, separate from those remaining in the swarmed colony?

Clearly this requires a bit more thought and research.

If your association invites me to discuss swarms and bait hives next winter I might even have an answer.

But, as with so many things to do with bees, knowing that answer will only spawn additional questions 😉

{{1}}: Freebees – bait hives for profit and pleasure.

{{2}}: To deliver at least … you’d need to ask the audience whether it was an enjoyable talk to listen to.

{{3}}: And work from others as well, in particular Martin Lindauer a protégé of Karl von Frisch, but Seeley and his PhD students have probably made the greatest contribution to this area.

{{4}}: Seeley actually has a section in Honeybee Democracy titled Mediocrity in 15 litres which is a bit of a clue!

{{5}}: Not quite the same thing.

{{6}}: More’s the pity …

{{7}}: And wolves, lynx, beaver, boar, bison, moose and wolverine … this really is not a good track record.

{{8}}: Not always … there are certain scientists who, like lawyers, only ask questions to which they already know the answer. This sometimes initiates a petty tit for tat exchange lasting the entire conference. We have name for colleagues like these …

{{9}}: To go with all the others I’d already used.

{{10}}: Nothing to see here … let’s move on.

{{11}}: And during an in person talk if you pause and think for a long time they assume you’re just forgetful, or stumped or stupid … I talk to some very perceptive audiences.

{{12}}: In fact, it’s probably happened a gazillion times before.

{{13}}: Some interesting changes must be involved in switching to a well lit horizontal dance floor outside the darkness of the hive. Do the bees seamlessly re-orientate the directional component of the dance away from gravity and to the sun?

{{14}}: Thom et al., 2007 The scent of the waggle dance. PLoS Biology 5:e228.

{{15}}: Some assumptions there as well … but bivouacked colonies often lack vertically-oriented faces.

Join the discussion ...