Battlefield bees

Synopsis: For millennia bees were used as weapons of war. They are now being developed as ‘weapons of peace’ to help clear the millions of anti-personnel mines left after active conflict ends. Their legendary scent detection abilities combined with high-tech ‘bee detection’ methods show promise and may help reduce the thousands of civilian casualties that occur decades after the war ends.

Introduction

The weekly posts on this website are about bees and beekeeping.

In the same way that I deliberately shun sponsorship and avoid advertising {{1}} I also try and avoid politics, law and other divisive subjects. These cause enough problems without adding my opinions into the mix … and worse, having to moderate the opinions of others in the subsequent comments.

So, although I might write about the detrimental effects of thiamethoxam on bees, I would focus on the science of neurotoxins rather than politics of lifting the ban of the use of this neonicotinoid in the UK .

It is harmful to bees, but the aphid-transmitted yellows viruses may otherwise decimate our sugar beet crop, and might not the alternative pesticides be more harmful to bees?

Do we even need that much sugar beet?

And what about the livelihoods involved?

You can see how quickly it gets very messy.

But, at the same time, I strive to make posts relevant and even topical. When viewed retrospectively – even if just by me – the posts represent a snapshot of my jumbled thoughts of what’s current at the time.

There are ageing posts on oxalic acid treatment that don’t reference ApiBioxal (the good old days as I like to call them), and others that make passing mention of maximising the oil seed rape (OSR) crop, or processing OSR honey {{2}}.

All of which means I cannot really avoid mentioning the recent Russian invasion of Ukraine {{3}}.

Six-legged soldiers and one-legged civilians

Two years ago I wrote a post about the use of bees in warfare. For many hundreds of years they were an effective tactical weapon to be dropped on or fired at the enemy.

Not individually – that would be just silly – but a hive at a time.

I’ve been present when someone has dropped a full brood box. The whirling cloud of angry bees was reminiscent in shape, though nothing else, to the mushroom-shaped cloud over Hiroshima. Lots of people got stung in the training apiary during that session.

Unfortunately, the ingenuity of man knows no bounds when it comes to killing and maiming others.

The thermobaric weapons employed today are very different from the torsion-powered ballista siege engines used by the Ancient Greeks over two millennia ago {{4}}.

Soldiers now wear carbon and kevlar rather than Corinthian helmets and short-sleeved tunics.

Although you can buy a camouflaged bee suit, it’s not designed for the battlefield, and is likely to be about as much use as the hoodies, jeans and T-shirts that the innocent civilians inevitably caught up – or deliberately targeted – in today’s wars are wearing.

The legacy of war

And long after the battle has ended – years or even decades later – those surviving civilians continue to be maimed and killed by unexploded ordinance and, particularly, by anti-personnel mines.

So, rather than dwell on the horrors of the present – which is about as far removed from beekeeping as it’s possible to get – I’m going to discuss some more hopeful stories of how bees might help reduce the deaths and injuries caused by anti-personnel mines.

Those readers expecting the (un)usual humour may be disappointed this week … this is not a topic that lends itself well to jokes.

The solutions that scientists are developing to detect anti-personnel mines use a clever combination of the truly awesome scent detection capabilities of honey bees coupled with some very clever technology.

The problem

In 2021 there were 61 countries which were ‘contaminated’ with anti-personnel mines. These mines are typically produced for a few dollars, are perhaps 30 cm in diameter and are buried just sub-surface … and often forgotten.

One definition of the word minefield is ‘a situation or subject presenting unseen hazards’. The plural hazards, and use of ‘field’, indicate that lots of anti-personnel mines are usually buried across an area, thereby rendering it too dangerous to enter.

Farming, trade and communication is inhibited as people have to avoid the minefield(s) … and, if they don’t then the consequences can be devastating.

The International Campaign to Ban Landmines recorded over 7,000 casualties in 2020, 2,500 of whom were killed.

80% of these casualties were civilians and – where the age was known – over 50% of the casualties were children.

Aside from banning the use of anti-personnel mines in the first place, a priority must therefore be to find and removes mines from these areas.

Typically this involves using metal detectors or sniffer dogs for detection, followed by manual clearance. Inevitably, there are considerable risks involved in both the detection and – to a lesser extent – the clearance. These risks make the process time-consuming and expensive.

Which is where honey bees come in …

”I love the smell of Napalm in the morning”

So said Lieutenant Colonel Kilgore (Robert Duvall) in the film Apocalypse Now.

Landmines don’t contain Napalm, but about 90% if them contain TNT (trinitrotoluene).

And not only does TNT have an odour, but landmines continue to emit this odour for years after they have been buried. On a calm day there are vapour plumes of TNT above each of the buried mines {{5}}.

The vapour concentration of TNT is measured in parts per trillion (pptr) and is usually in the range 0.01 – 100 pptr.

Just as the usual way to express areas is by comparison to Wales {{6}}, the ‘volume comparison’ is typically made to an Olympic swimming pool.

1 part per trillion is about the same as half a teaspoon added to an Olympic swimming pool. Not very concentrated …

… but well within the detection capabilities of honey bees. For comparison, this is similar to that of sniffer dogs {{8}} trained bees to feed on syrup laced with trace quantities of TNT. They then tested the ability of these bees to detect targets emitting field-realistic amounts of TNT.

The results were very encouraging. 97-99% of targets were detected with 1-2.5% of false-positives.

More importantly, the false-negatives (targets that were missed) were less than 1%. It’s much more important to not miss any than to ‘find’ some that aren’t there.

Lidar

The authors neatly sum up the benefits and principles of the study:

Bees do not cause mines to explode, do not require a handler, and can be trained more rapidly than dogs. This technique makes use of the natural foraging behavior of bees, which frequently cover ranges up to several km around a hive. The bees identify the sample location by their increased dwell time while flying in its vicinity.

And it’s that last sentence that should give you pause for thought.

How do you detect the “increased dwell time” – a fancy term meaning spending more time flying in one small area than the remainder of the study area – if you’re trying to find mines in an area about the size of a couple of football pitches {{9}}.

Remember, as if you’d forgotten, you cannot enter the minefield because of those unseen hazards that are lurking just under the surface waiting to blow your legs off.

Bees are pretty small. I can see them against the clear blue sky at 20-30 metres range, but I can’t see them against mixed foliage at anything like that distance.

One potential solution is light detection and ranging (lidar) technology. Essentially this involves shining a scanning laser across an area and detecting the light scattered when it ‘hits’ objects – such as flying bees {{10}}. For additional discrimination, changes in the polarisation of the scattered light has been used to distinguish between bees and what the scientists termed ‘clutter’, which I take to mean foliage.

And it works.

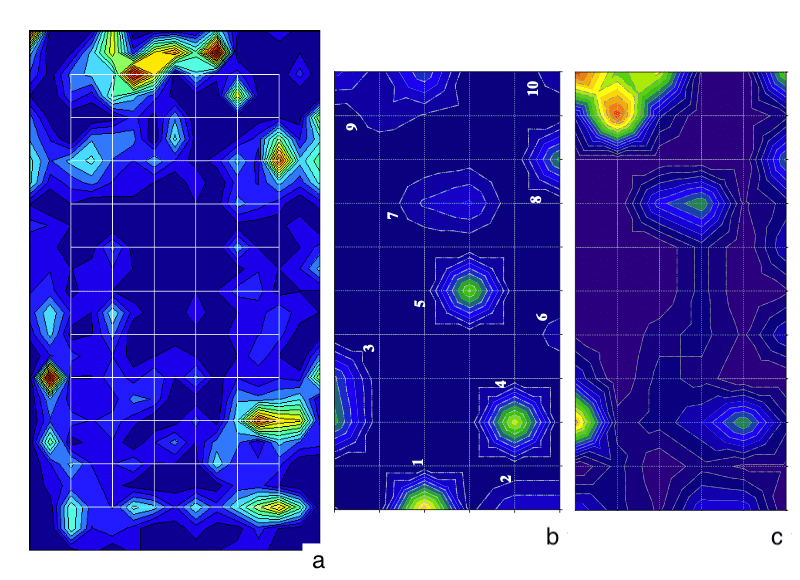

Lidar detection of bees; a) bee heatmap, b) chemical detection (5 is a false positive), and c) visual mapping of bees.

Not only in theory but also in practice … lidar has been used to detect bees detecting mines in an active ‘minefield’. Mines were buried in known locations, trained bees were released and their ‘dwell times’ were recorded using lidar (with the detector about 80 metres away).

Football fields and minefields

But there’s a problem.

Lidar involves a laser scanning horizontally 30-60 cm above the ground. Anything lower than this and the foliage prevents accurate (or any) detection of the bees.

And, even though a minefield might be the size of a football field, it doesn’t look like a football field … either when mined in the first place and definitely not after a few years.

Unfortunately, there’s also an additional problem.

Tragically the sign above was probably erected after someone inadvertently stepped on a mine. Until that fateful day it might have just been ‘that scrubby bit of field bordering the river’.

Detecting the location of mines in a minefield is one problem.

Detecting whether a field is a minefield is a different – albeit related – problem.

And it turns out that bees might be able to help us discriminate between minefields and football fields, or any other sort of equally harmless fields.

I’ll discuss this before returning to the detection of individual mines in a minefield.

REST (and be thankful)

REST is an acronym for Remote Explosive Accent Tracing {{11}} .

Since those buried anti-personnel and landmines give off a vapour plume of TNT there are methods of sampling the air and testing it for the presence of trace amounts of explosives.

The ‘sampling’ is highly technical and outside the scope of this post {{12}}.

The ‘testing’ involves sniffer dogs and lots of doggy treat-type rewards. Consequently it is a time-consuming and therefore costly procedure.

However, honey bees are covered in tiny hairs. Through electrostatic interactions, these pick up molecules while they are out foraging. Graham Turnbull {{13}} and colleagues have shown that flying bees can pick up molecules of TNT (from buried mines) which can subsequently be detected.

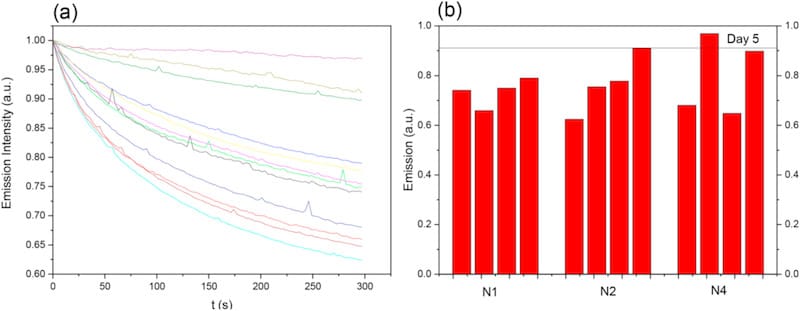

The bees are therefore used for wide area sampling, but how is the TNT detected? Graham is a physicist whose speciality is organic semiconductor sensing films … essentially thin films that change fluorescence when certain chemicals are deposited on their surface.

The hive entrances were modified so that the bees passed through a tube. This was made of a special material to pick up – and since lots of bees were making the trips, to also concentrate – the molecules that adhered to their hairs whilst out foraging.

To cut another long story short, the concentrated molecules were then transferred to the semiconductor sensing film and the photoluminescence quantified. A reduction in the photoluminescence (quenching) was indicative of TNT detection {{14}}.

So honey bees can be used to discriminate between minefields and, er, other fields.

Detecting mines not minefields

I should add that the bees used in the study above were not trained {{15}} in any way. They simply placed feeders on the opposite side of the uncontaminated test or mined field to encourage them to sample in a reasonably defined area. The bees were not searching for mines, or the TNT vapour plumes, they were just flying back and forth ‘doing their stuff’ and foraging.

Bees are fast learners and can – as described briefly above – readily be trained to associated particular scents (such as TNT) with rewards (i.e. syrup). When you release these trained bees into an area with TNT vapour plumes they home in on these looking for the rewards … and hence exhibit those previously mentioned ’increased dwell times’ near buried mines.

But there’s still the problem of how the bees can be detected.

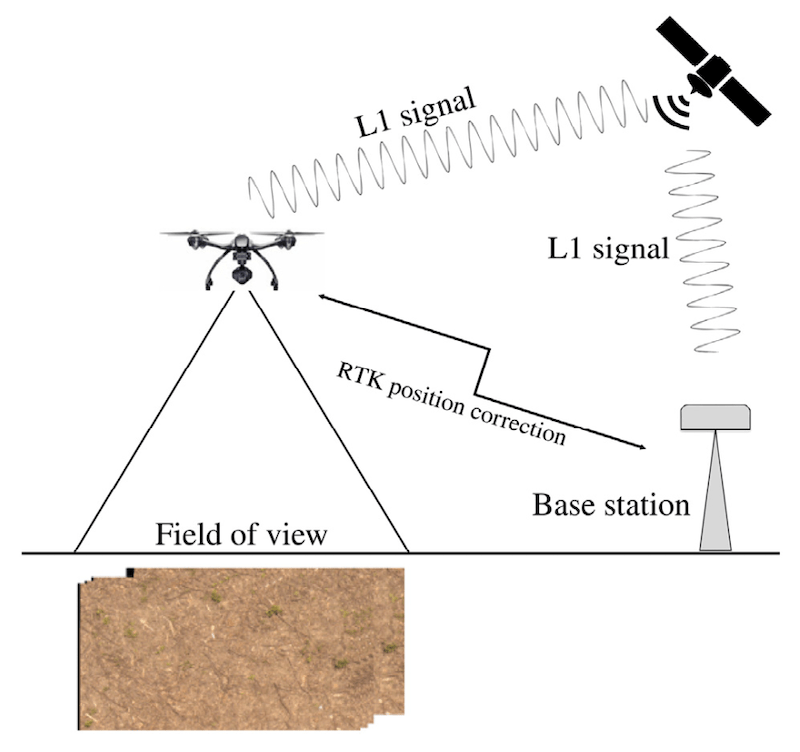

Huge advances have been made in unmanned aerial vehicles (UAV’s or drones), GPS and video technology in the 15+ years since the original use of lidar to detect bees detecting landmines.

The combination of these technologies now provides a way to detect individual bees, and consequently anti-personnel mines, within an area.

A drone flying 10 m above the minefield {{16}} was used to record high resolution video from which the locations of individual bees could be (computationally) determined.

By detecting bees on individual frames (from video taken at 45 fps), rather than tracking each bee, it was (again computationally) relatively straightforward {{17}} to generate spatial density maps showing where the bees preferentially concentrated.

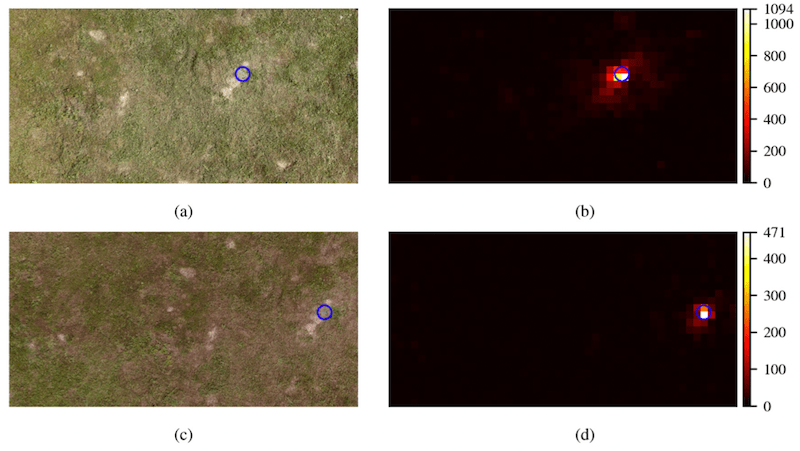

Video stills (left) and bee location heat maps (right). The blue circles show mine locations. Bee numbers on scale.

The accurate spatial location was ensured by using a modification (RTK) to GPS which involved an additional ground base station. This increased the standard GPS resolution to provide a horizontal accuracy of 5 cm. The bright coloured foci of ‘increased dwell times’ were less than 0.5 x 0.5 m.

Conclusions and problems

These studies are encouraging. They suggest that a biohybrid system {{18}}, combining advanced physics and area-wide sampling of bees, with the exquisite scent detection of trained foragers coupled with highly accurate video monitoring, might help reduce the number of victims of landmines that occur long after the original conflict ended.

However, there are a few problems that remain to be resolved.

Bees learn fast, but they also forget fast. The authors developed some reinforcement training exercises to ‘remind’ them that they were searching for things scented with TNT.

Bees are not ideal chemical biosensors. They are potentially easily distracted by a strong nearby nectar flow, they don’t forage {{19}} in poor weather and their availability might be seasonal, depending upon the latitude.

Drones have limited flight times and long vegetation still impedes accurate video detection. Either the bees fly at lower altitudes or the foliage is disturbed by rotor downwash and so increases background noise.

Nevertheless, the expected costs and time involved in both the wide-area sampling and mine detection are lower, and the mine detection per se is much safer.

The mines still have to be destroyed, but knowing precisely where they are – and where they are not – is much more than half the battle … in solving the lethal legacy of a possibly long-forgotten battle.

{{1}}: I receive daily emails suggesting promoted posts and generous offers of things to “review”. All are politely refused, or – more usually – impolitely tossed into the spam bin.

{{2}}: Neither of which really apply out here on the wild west coast of Scotland.

{{3}}: As an aside, it’s noticeable that visitor numbers have dropped significantly since the war started. I’m aware that other ‘bloggers’ or whatever the correct term is have made the same observation. It’s worth remembering that there are more important things than bees.

{{4}}: Another example of the good old days.

{{5}}: It’s presumably there on a windy day as well … trailing downwind of the mine.

{{6}}: Check out the size of the Death Star.

{{8}}: My dog has no nose … Really? How does he smell? … Terrible![/efn_note].

To cut a long story short, scientists 7Bromenshenk et al., (2003) “Can honey bees assist in area reduction and landmine detection?,” J. Mine Action 7.3

{{9}}: Which, although a lot smaller than the size of Wales, is still quite big.

{{10}}: Inevitably, I’ve dumbed that explanation down as I don’t fully understand it myself.

{{11}}: ”… and be thankful” is for Scottish readers who will recognise this as highest point on the landslide-prone A83 in Arrochar. It’s a beautiful spot (to be stuck in a traffic jam) but totally irrelevant to the remainder of this post.

{{12}}: And my very limited understanding of physics involved.

{{13}}: He’s a colleague of mine at the University of St Andrews.

{{15}}: Or for that matter harmed.

{{16}}: We don’t have any minefields in St Andrews … the fieldwork was done with Croatian collaborators.

{{17}}: Gross understatement … it involved ‘convoluted neural networks’ and some major ‘big forehead’ geekery.

{{19}}: For nectar or landmines.

Join the discussion ...