Tragedies and triumphs

Synopsis: Beekeeping shouldn’t be “a series of calamities then winter”, though it sometimes feels like that. In the first of a two-part post I look at the real and imagined disasters that can befall you during the season. The reality is that the observant and well-prepared beekeeper can avoid most of the ‘tragedies’, and recover from almost all of them.

Introduction

A few weeks ago I did a live-streamed Q&A with Laurence Edwards from Black Mountain Honey. Some of the questions were both good and interesting, some of the answers were perhaps less so. Before any readers think I’m being rude here I should point out that Laurence was asking the questions – often on behalf of others – and I was answering them.

There were quite a few questions on non-chemical treatment which I was singularly ill-equipped to deal with. Not because I don’t know anything about it, but because I don’t practice it {{1}} and because I suspect I’m not a good enough beekeeper to be successful if I did try it. There’s clearly a lot of interest in the topic, though I fear much of this is also from beekeepers who are not sufficiently experienced to succeed with it either.

However, there were two questions – or perhaps it was one merged question – that went something like this:

What is your greatest beekeeping success and your biggest beekeeping disaster?

I’m paraphrasing here. I can’t remember the precise wording and daren’t review it on YouTube as I’d then have to listen to my erudite insights inchoate waffle … which would be excruciating.

My answer probably involved asking whether I was restricted to just one disaster … 😉

Let’s get some perspective first

New beekeepers in particular are likely to worry about the “disasters” and overlook some of the “successes” in their first season or two. I therefore thought I’d discuss what I consider are the highs and lows – abbreviated to ‘tragedies and triumphs’ to give the post a snappy title – of the first few years of beekeeping.

Obviously this is biased and based upon my own experience, and from mentoring others. Your experience may be very different … or you may have yet to experience the highs and lows of a beekeeping season.

But before I start using superlatives to describe the chaos of my early efforts at swarm control it’s worth remembering – particularly as the war in Ukraine enters its third week – that I’m only talking about beekeeping here.

In the overall scheme of things it’s simply not very important.

What might feel like a disaster of biblical proportions in the apiary … isn’t.

Yes, it might threaten the productivity, or even the survival, of the colony, but it is only beekeeping {{2}}.

So, having got that out of the way, which do you want first?

The good news or the bad news?

The bad news … how mature 😉

The loss of a hive tool

Clearly I’m being flippant here.

The loss of a hive tool is a minor inconvenience rather than a tragedy.

Unless you don’t have a spare and/or you’re about to inspect a dozen heavily-supered hives in the apiary … in which case it’s a major inconvenience.

It’s remarkably easy for a hive tool to fall out of those tall, thin pockets in the sleeve or thigh of your beesuit. Inevitably it falls, not onto closely cropped sward, but into tangled tussocks of rarely-mown grass.

You will probably find it again.

You could spend 15 minutes on your hands and knees retracing your steps since you left the car or you could become a detectorist and conduct a grid-based search, sweeping the area for metal objects.

Neither method is guaranteed to work.

To be certain, you must cut the grass.

But be careful. A glancing contact with the lawnmower or brush cutter and a half-buried hive tool will be damaging at best, and potentially a lot worse 🙁

Or you can avoid all this grief by keeping a covered bucket in the apiary – a honey bucket is ideal – containing a strong solution of soda crystals. You know exactly where the hive tools are and you soon get into the habit of dropping it back in after an inspection.

Better still, keep two hive tools in the bucket and alternate them as you look at your colonies. The soaking in soda will clean the hive tool, reduce any potential cross-contamination and improve your apiary hygiene.

The loss of a queen

This can be anything from a minor inconvenience to a bit of a calamity.

It very much depends upon the:

- time of the season

- whether you notice she’s missing

- availability of a spare colony

How do you lose a queen? Other than by losing a swarm (see below) the two most likely reasons are cackhanded beekeeping or a queen that fails due to being poorly mated.

Losing a queen mid-season, for whatever reason, should be little more than a minor inconvenience. Assuming you notice she’s missing in action you can remove unwanted queen cells, leaving a single charged (i.e. known to contain a fat larva lounging around on a comfortable bed of Royal Jelly) cell, and wait while she pupates, emerges, mates and starts laying.

Nerve racking? Perhaps slightly, but it’s usually a pretty safe bet that things will work out OK.

If, through clumsiness or stupidity {{3}}, you kill the queen during an inspection there should be ample eggs and young larvae for the colony to use when rearing one or more replacements.

Keep your eyes peeled …

But what if you don’t notice she’s missing? You assume she’s there and blithely knock back all the queen cells you can find {{4}}.

You return the next week … all looks good, no more queen cells.

But wait a minute … there are no eggs either 🙁

Under these circumstances you realise the importance of having at least two colonies. You can rescue the queenless colony by donating a frame of eggs from a queenright colony.

Queens also fail because they are poorly mated. They either stop laying, or they stop laying fertilised eggs (i.e.they continue to lay unfertilised ones, leaving you with ever-increasing numbers of drones in the colony). The colony might realise and supersede her, or you might be able to rescue the situation with a donated frame of eggs.

I’ll deal with the consequences of a failed or slaughtered queen at the extremities of the season – early or late – below.

The loss of a swarm

It happens to the best of us, and it sometimes seems to happen even if you do your swarm prevention and control by the book {{5}}.

I’ve turned up in the apiary on a warm May afternoon to discover a whirling mass of bees swarming from one of my hives {{6}}.

It’s not a disaster … in fact it’s one of the greatest sights in beekeeping.

With luck the swarm will bivouac nearby and you’ll be able to collect them in a skep and re-hive them late in the afternoon.

At least it shouldn’t be a disaster, but Sod’s Law usually dictates that …

- if you’re there when the swarm emerges, and

- you have a skep and sheet with you

… the swarm will alight 45 feet up a Leylandii 🙁

Even then it might end well if you’ve got a suitable bait hive set out nearby.

The time when losing a swarm is a disaster {{7}} is when you don’t realise you’ve lost a swarm. You find some queen cells, hurriedly knock them all back {{8}} and then wonder why there are no eggs the following week.

Déjà vu

At which point you’re in a similar situation to the ‘loss of the queen’ I described above … except you’ve also lost up to 75% of the workers from the colony. The situation is still rescuable with a frame of eggs from your other hive {{9}} but you’re likely to miss out on the major nectar flow.

Could the situation be any worse?

Oh no it can’t … Oh yes it can!

You miss the lost the swarm, you knock back all those queen cells and you then fail to realise there are no eggs or young larvae in the colony until only sealed brood remains (i.e at least 9 days).

Or worse still, until no brood remains (i.e at most 21 days).

With no brood pheromone being produced there’s now a real danger that the colony will develop laying workers. Things now get an order of magnitude more difficult as a colony with laying workers is very difficult to requeen (and generally will not even attempt to rear their own if presented with a frame of eggs).

You’re fast approaching the next of the beekeeping ‘disasters’ …

The loss of a colony

How do you lose a colony?

What was it Elizabeth Barrett Browning said? ’Let me count the ways’ {{10}}.

Natural disasters such as falling trees, winter gales, raging floods, woodpeckers, honey badgers and stampeding elephants {{11}} can destroy a colony.

However much care you take – avoiding floodplains, strapping the hives down, seeking shelter (but not near shallow-rooted trees) – sometimes sh1t just happens {{12}}.

You did your best and nature did her worst.

See what you can rescue and try again next year.

Queen loss at the start or end of the season

Losing a queen very early or very late in the season – for whatever reason – is a problem. There’s no chance of the colony rearing another – it’s too cold and/or there are no drones available. I suppose there’s an outside chance you could requeen the colony – if you had a queen available {{13}} – but doing so involves quite a bit of risk.

If the queen fails overwinter, all the bees in the box will be very old by the time your colony inspection confirms she’s firing blanks, or not firing at all. The chances of successfully requeening the hive are slim at best.

Although that colony is effectively lost – at least if it happens late in the season – it’s not an unmitigated disaster if you have another hive {{14}}. You can unite the queenless colony over a queenright colony very late into the autumn, strengthening the latter and (at least) using the bees from the former, rather than condemning them to a lingering death.

I wouldn’t bother trying to unite a queenless colony (or one with a failed queen) at the very beginning of the season. The remaining bees will be pretty decrepit and there won’t be many of them. It’s unlikely they would contribute in a meaningful way to the successful build-up of another colony.

Winter losses through starvation

These are unfortunately common and often entirely avoidable.

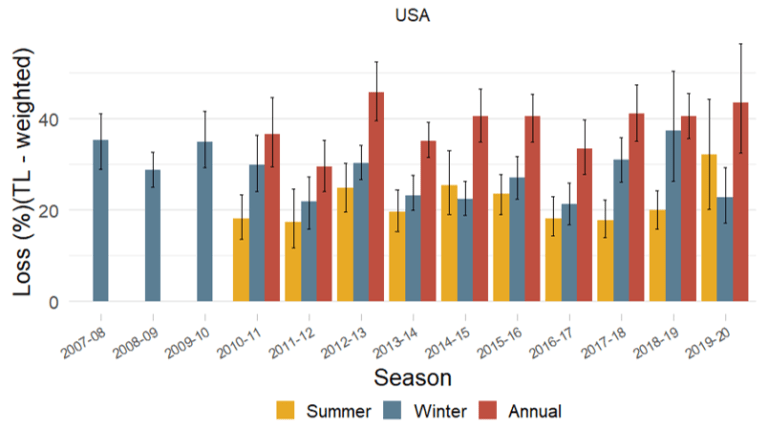

Small-scale surveys from the BBKA and SBA often report winter colony losses of 20-30%, and up to 50% in some years. Large scale surveys, like the Bee Informed Partnership (BIP) one in the USA, have reported annual colony losses – the majority of which occur in the winter – exceeding 40% in all but two years since 2013.

I’ve lost colonies through both starvation and disease.

In both cases it was entirely my fault 🙁

It was a disaster for the bees and it was a sobering and educational experience for me.

I discussed starvation, and how to avoid it, in winter weight a couple of weeks ago. I won’t rehash it here, but I will repeat again that the bees are still in the ‘danger zone’.

There’s little nectar available and they are busy rearing brood. Their need for stores is probably higher now than at any time over the last 4-5 months.

At best, a shortage will hold the colony back. At worst they’ll die of starvation.

All of which is completely avoidable by ensuring they have ample stores at the beginning of the winter, and then by keeping an eye on the weight of the colony as they enter the spring. If you’re adding fondant in late December it’s likely the colony had insufficient stores to start with … but at least you’re keeping a check on the weight of the colony.

Winter losses due to disease

I suspect that the majority of winter losses are not due to starvation but are instead due to inadequate or incorrect Varroa management.

This is a topic that has been covered numerous times in posts here. The most recent overarching review of the topic is probably Rational Varroa Control. Versions of this appeared in the August 2020 BBKA Newsletter and in The Scottish Beekeeper in the same month.

Successful Varroa control requires an understanding of the treatments available and the pros and cons of using them on your bees and in your location/climate. Too many beekeepers simply want to know whether they should add Apiguard in the third week of August or middle of September.

Unfortunately, it’s not quite that simple.

But that doesn’t mean it’s particularly difficult either.

Unlike many of the other diseases of honey bees – e.g. chronic bee paralysis virus (CBPV), Nosema and the foulbroods – there are effective treatments to control Varroa and the damaging viruses that it transmits.

Losing a colony in June to CBPV is possibly unavoidable (it’s just bad luck) but losing one to Varroa/DWV in January – which is largely avoidable – might well be bad beekeeping.

In both cases of course it’s a disaster for the colony 🙁

Disaster

The meaning of disaster is ‘An event or occurrence of a ruinous or very distressing nature; a calamity; esp. a sudden accident or natural catastrophe that causes great damage or loss of life’. Its origins date back to the mid-16th Century.

Some of the ‘disasters’ I’ve described above involve the loss of just one life – that of the queen. For the reasons I describe, they’re not really disasters at all, or shouldn’t be for the observant and well prepared beekeeper.

They become disasters i.e. causing great damage or loss of life, if you miss the tell-tale signs and so contribute to the eventual demise of the colony.

The avoidable loss of a queen or a colony is a distressing experience, or at least it should be {{15}}.

If it is distressing then it will probably also be a learning experience.

Analyse what went wrong and work out how you might prevent it happening again in the future.

We have a duty of care for the bees we manage. I don’t like losing colonies, but it still happens infrequently. When it does I try and determine whether it was just fate … or my incompetence (or – let’s be generous – my actions or inactions) that caused the loss.

And the times you manage to work out where you went wrong are the foundations for your beekeeping triumphs in the future … which is what we’ll return to next week.

{{1}}: Not entirely true of course … on the west coast of Scotland my bees are all treatment free because they’re Varroa-free.

{{2}}: It was Bill Shankly that said “Some people think football is a matter of life and death. I don’t like that attitude. I can assure them it is much more serious than that.” and at times I feel the same about beekeeping. But it’s not.

{{3}}: Two distinct but related skills some beekeepers appear to have … including me in earlier days (edited in the interests of honesty).

{{4}}: Perhaps now is the place to remind you that you that the presence of queen cells in the colony is a signal that should not be ignored … just knocking them all back is very rarely the right course of action.

{{5}}: Though the very fact it’s happened suggested you didn’t read the book well enough.

{{6}}: More than once, and not just in May.

{{7}}: Please re-read the Let’s get some perspective first paragraph, these things are all relative.

{{8}}: The phrases ’mashing them down with a hive tool’ or ’squidging them between finger and thumb’ are more accurate, but perhaps a bit too detailed.

{{9}}: What? You’ve only got one hive? Quack quack, oops. Go directly to jail. Do not pass GO, do not collect £200.

{{10}}: To be factually accurate I should point out that her Sonnet 43 was not about colony losses …

{{11}}: The Apiarist has an international readership and I need to ensure the writing remains relevant wherever possible. In fact, elephants don’t like bees and try and avoid them.

{{12}}: Though, touch wood, I’ve managed to avoid ratels and elephants … so far.

{{13}}: A topic we’ll deal with next week.

{{14}}: Is that an echo? Where have you heard that before. Here perhaps?

{{15}}: I don’t believe it’s distressing for the bees though … that requires sentience.

Join the discussion ...