Google maps and apiary security

The increased interest in beekeeping over the last few years has meant there is considerable demand for bees, either for beginners or to replace stocks lost over the winter. The impatient and unscrupulous have resorted to bee rustling, either directly or indirectly. It is therefore sensible to take precautions to prevent the theft of your hives and nucs. This subject was covered extensively a couple of years ago in a post on Beekeeper UK (now defunct, or at least disappeared) which described branding, locks, ground anchors and other deterrents and is recommended reading. However, one aspect of security worth reinforcing is the impact of new digital technology – specifically smartphones and satellite imagery – which can be used to locate hives.

GPS-tagged image

Smartphone cameras (and many new digital cameras) embed the GPS coordinates into their images. This information is contained within the exif (an abbreviation for exchangeable image file) data in the image, which also includes details of the camera, exposure etc. This can be readily viewed using online tools such as Jeffrey Friedl’s Exif (Image Metadata) Viewer (gone, but there are lots of others). To illustrate this I’ve uploaded an image (right) taken when out cycling – so not compromising my own apiary security – with an iPhone a few years ago. If you point the Exif Viewer at the image you can extract all the embedded information, including both the GPS coordinates and a Google Maps view, as shown here (site disappeared since this post was written). You can then use Google Streetview to see the, er, street view of the scene (if their little cars have visited).

Google Streetview …

So what? I don’t share my images online …

OK, so much for the introduction to a potential problem, why should it be of interest or relevance if you don’t post GPS-tagged images on your personal blog, Facebook page, Instagram account, internet discussion forums, Flikr, 500px etc.?

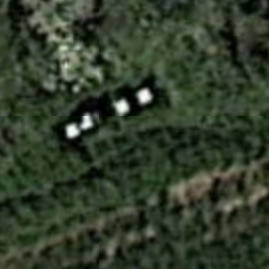

Baton Rouge labs

The real problem isn’t the GPS-tagged images at all (I’ll describe an easy solution to this later in this post), rather it’s the resolution of the online satellite images provided by Google, Bing and others. These are good enough now to locate apiaries relatively easily and to see individual hives in certain circumstances. They’re also going to get a lot better soon. Rather than compromise an amateur beekeeper, or publicise an otherwise hidden apiary, here is an image containing three rows of hives (on rail stands) at the ARS Honeybee breeding, genetics and research labs in Baton Rouge, Louisiana, USA … I think it’s fair to say it’s no secret that they’ll have apiaries on site 😉 And below is the view from ground level, taken in a different season with the trees in full leaf. The cars in the satellite image provide a sense of scale.

Baton Rouge apiary …

Google Maps (and Bing and others) satellite imagery are of similar resolution for the USA and the UK. The satellite image above is not even at maximum size … when it is you can pretty easily count individual hives. This was brought home forcefully when processing a smartphone image (with embedded GPS coordinates) in Adobe Lightroom. The Map module showed a neat row of hives in the corner of a field. Google updates the images they use reasonably frequently, so even if your colonies are not visible now they might be soon after the next satellite passes over.

Security by obscurity

How can you prevent your apiary from being detected? Of the local apiaries I’m aware of I couldn’t detect those that:

- were located under light tree cover. This would seem to be both practical and relatively easy to achieve. As long as they are not in deep shade it can also make for a much more pleasant inspection experience on a sweltering hot day, and the trees or hedges can provide shelter from strong winds.

- contained only individual hives. Whilst absence of evidence isn’t evidence of absence it is certainly easier to detect neat rows of hives along field boundaries or angled across the corner of a meadow.

There you are!

The most obvious hives were those in which the roof contrasted with the ground. This was particularly marked with bright, shiny, metal roofs glinting in the sun. Older, tattier, hives or those with roofs covered in roofing felt were more difficult to find. Perhaps it might be worth applying camouflage paint to new hive roofs. Irregularly placed hives in dark or muted colours that didn’t contrast with the ground were generally tricky to see.

None of these precautions are foolproof. None of them negate the need to keep your colonies in secure, private locations, preferably behind locked gates. However, they might be useful in preventing unwanted attention.

But what about my online images?

Some image hosting sites automagically strip location-sensitive information from uploaded images. Others do not. On the principle that it’s better to be safe than sorry it’s worth always ensuring the uploaded images do not contain this information. Phones usually have an option to exclude GPS data from images. Alternatively (and to avoid omitting the location information from all the images you want to keep it in) it’s easy to strip unwanted exif data, including all the GPS data, using software. If you’re an Adobe Lightroom user this is an option under the ‘export’ menu. Alternatively, ImageOptim is an excellent (and free) Mac application that compresses images, strips out unnecessary metadata including all the location information and removes unnecessary colour profiles. This typically reduces the file size by 10-20% and works with a range of graphics format images. The image per se is unaltered. It runs as a Service on the Mac, which makes it even easier to use.

The GPS-tagged image of the bike on the fence at the top of the page is 242 kB. After using ImageOptim this is reduced to 213 kB in size. More importantly, as far as security is concerned, Jeffrey’s Exif Viewer (gone 😞 but this article is 11 years old, so understandable) now shows no geographical information. It even hides the embarrassing fact that my smartphone is over four years old 😉

There are also ways of removing exif data from your images if you use Windows. I’ve not used these and cannot comment on how well they work.

Join the discussion ...