Honey pricing

The best way to start beekeeping is to learn by example.

Join an association, go to a ‘Beginning beekeeping’ course over the winter and browse the catalogues.

Get a mentor, buy a nuc of well-behaved local bees in May/June and enjoy yourself.

And talk beekeeping with other beekeepers.

Ask questions, lots of them

In case you’ve not noticed, if there’s enough tea and digestives available, beekeepers can talk a lot. Ask three beekeepers a question and you’ll get at least five answers {{1}}.

They’ll talk about swarming and queen rearing, about how imports are ruining beekeeping and about hive designs.

They’ll discuss how imported queens head calm and productive colonies and why ‘brood and a half’ is the solution to most beekeeping problems {{2}}.

Some will enthusiastically talk about half-assed DIY ‘solutions’ to barely existent problems or why comparisons between treatment-free beekeeping and anti-vaxxers is unfair {{3}}.

They’ll talk about anything, agreeing and disagreeing in equal measure.

Well, not quite anything

The observant tyro will notice that there are a few topics on which experienced beekeepers are a bit less opinionated or, er, helpful.

Could you help me requeen my ‘colony of sociopaths’ this weekend?

Can you give me the phone number of the farmer with 40 acres of borage?

How did you prepare that prizewinning wax block for the annual honey show?

How much do you charge for your honey?

And not just unhelpful … they can be downright evasive.

Healthy competition

Topics like these are where beekeeping becomes a competitive pastime (except for the requeening one, which is simply self-preservation).

That’s not necessarily a bad thing. We want the best forage for our bees so that colonies are strong and healthy. We want good nectar sources so that supers are heavy and numerous. We want to win ‘Best in Show’ so we can add the magic words ‘Prizewinning local honey’ to our labels which – for some at least – means we’ll be able to charge a premium for our honey.

Vulture

And there’s nothing wrong with any of that.

But think back to when you were a beginner.

That first year you had a real surplus of honey {{4}}.

After the circling vultures of friends and family had had a jar or two for their porridge/tea/toast or acne {{5}}. After you’ve sold half a dozen jars at the village fete, or to colleagues at work.

When you’ve actually got quite a few jars left over you’d like to sell ‘at the door’, or through an excellent local organic cafe or outstanding artisan cheese shop {{6}}.

How much do you charge for your honey?

Firstly, if you’re in precisely this situation, don’t expect any simple answers here.

But also don’t necessarily expect any straight answer from your beekeeping colleagues.

Assuming you’re not actually dependent upon the income, in a way it doesn’t really matter what you charge. As long as you recoup your costs – jars, labels, petrol, Apivar, fondant etc. – you’ll have a hobby that pays for itself and gives you enjoyment {{7}}.

That sounds like a pretty good deal to me.

You can’t really ask for any more than that.

Except you can.

If you charge £3 a pound and cover your costs you might be able to charge £4.50 a pound and buy a new hive tool.

Or hive.

In your dreams

Or something totally unrelated to beekeeping that you’ve always wanted.

Like a Harley Davidson Softail Fat Boy 😉

Or you could charge £9 a pound and have a busman’s holiday in New Zealand every winter with the Manuka honey farmers.

Or you could charge £12.50 a pound … and sell virtually none of it because the beekeeper down the road is only charging £3 and you can buy *&%$£’s Everyday Essentials honey for 99p {{8}}.

Tricky.

What is the competition?

Not inexpensive

With few exceptions, supermarket honey is cheap. Where there are exceptions it’s because the honey is either inexpensive … or exorbitantly priced Manuka.

Cheap and inexpensive aren’t the same thing at all. The former is produced down to a price, like the jar mentioned above priced just below the psychologically important £1 threshold.

I’d bet that any almost honey produced by a local beekeeper, whatever the forage available, however poorly it had been filtered or presented, would be better than most of these cheap supermarket honeys.

I should note in passing that any comments I make here assume the honey is actually honey (it’s not corn syrup for example) and that it’s not fermenting and hasn’t been overheated during preparation. The first of these regularly occur in the millions of tons of ‘honey’ traded globally each year, whereas the other two are more likely to be problems encountered – or caused – by inexperienced amateur beekeepers.

The inexpensive supermarket honey is (usually) bought and sold in bulk, blended, often nicely labelled and attractively packaged. It’s perfectly good honey. It’ll probably taste OK and it might sell for £3 to £4 for 340 g.

The exorbitantly priced Manuka honey is an oddity. It might well be fake and it tastes pretty awful in my view. It’s a marketing triumph of hype over substance.

So is £4 a jar the baseline?

It depends upon the size of the jar 😉

It also depends upon the effort you are prepared to make on the bottling, labelling and marketing {{9}}.

But you’re not bottling, labelling and marketing bulk produced, blended, imported ‘Produce of EU and non EU countries’.

What you have is a far, far more valuable product than that.

You’ve had complete control over its production from start to finish – from siting the hives, through extracting, storage and jarring.

Local apiary, mid-July 2018

The provenance of the honey is without question.

There’s very few products sitting on supermarket shelves that you could say that about.

It’s very rare. This doesn’t in itself make it valuable. After all, Ebola is thankfully very rare in the UK. However, for some people (actually many people) buying something that’s not available in every supermarket across the country is a distinct plus point.

It’s rare and its availability is limited because it’s local honey. You’ve not got 5,000 colonies spread over half a dozen postcodes in the county {{10}}. There aren’t barrels of the same stuff in warehouses across the country {{11}}.

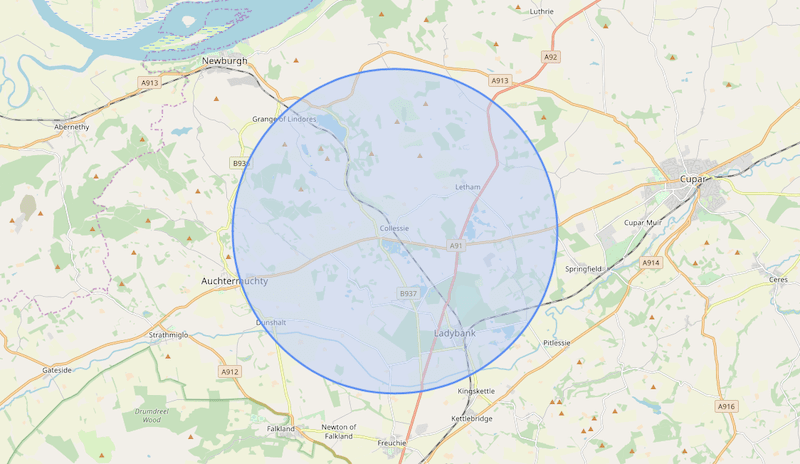

What you’ve got is a few buckets of mixed floral honey from about 9 square miles (at most, probably significantly less) of the countryside around your apiary.

Known provenance

And local honey should attract a premium price.

Many people want to buy local produce and eat local food. Their definition of local and the one I use above may not align perfectly. For me, local might be the two shallow valleys and the arable farmland my bees forage in.

For the potential buyer, ‘local’ might be anything within Fife (about 500 square miles).

And Fife has a population of about a third of a million people. Which is a lot of potential customers wanting ‘local’ honey. Which means demand should or could be high.

Which, in turn, increases the price you could sell your honey for.

So, I reckon that £4 a jar is about the lowest amount you should charge.

If you can find small enough jars 😉

The £10 ceiling

But what about slightly larger jars? After all, small jars are a pain to fill. How much can you realistically charge for a one pound (454 g) jar of honey?

At the moment the upper limit seems to be about a tenner.

If you look at ‘high-end’ outlets selling good quality local produce you’ll find that there appears to be an upper price limit of about £10.

Remember that this price includes a shop markup of perhaps 20-30%. After all, they have staff, rent, insurance and other costs to cover.

Which perhaps finally gets near the answer to ‘How much do you (or can I) charge for honey?’

Go and look in local outlets and see what they are charging for truly local honey. Not the (perfectly fine quality) honey from the larger regional suppliers (this isn’t local, it’s regional at best and, more likely, national), but the stuff from individuals within 10-15 miles or so.

Take off the guesstimated markup and that’s a reasonable guide to the price {{12}}.

What?

There isn’t any on the shelves?

This can only mean one of three things:

- They’ve already sold out because demand is so high = opportunity 🙂

- There aren’t any local beekeepers selling local honey = opportunity 🙂

- The shopkeeper has yet to realise the benefits of selling local honey = (yes, you guessed it) opportunity 🙂

I’m going to return to this topic several times over the winter.

In the meantime, back to the borage and that prizewinning wax block …

Oh dear, I’ve just reached 1500 words which is my (oft-ignored) self-imposed cutoff for waffle each week.

Those subjects will have to wait 😉

Note

This post first appeared in October 2019. Please note that the prices quoted are now significantly out of date. Fred on the allotment is still selling his honey at £3/lb but with a little effort he should be selling it at £11-12/lb 😉

{{1}}: One of which will be about brood and a half.

{{2}}: It isn’t.

{{3}}: They’re not … half-assed, barely existent or unfair.

{{4}}: Which probably wasn’t your first year.

{{5}}: Yes, really. And I’m assured it works extremely well. I’m going to write about medicinal uses of honey sometime over the winter.

{{6}}: I bet neither of those were caught by your Ad-blocker!

{{7}}: And what if you don’t recoup your costs? Think about the fun you’ve had. My son once calculated I’d need to sell honey at £468 a jar to “break even”. I’m still not sure I trust his maths.

{{8}}: Admittedly that price is for a strikingly unattractive 340 g jar where the contents (largely concealed behind an all-encompassing and spectacularly ugly label) are from ‘EU and non EU countries’ … whatever that means. Why don’t they just use ‘Produce from the cheapest place we could source it’ instead?

{{9}}: I’ll deal with this another time. I know I’m going to run out of space and time.

{{10}}: And hopefully no-one else has either.

{{11}}: But there probably are of the inexpensive supermarket honey.

{{12}}: All other things being equal. The honey still needs to look good in the jar, it needs to be distinctive and – of course – it needs to taste good. The latter is probably the easiest of these to achieve.

Join the discussion ...