Hydroxymethylfurfural

Excuse me?

Hydroxymethylfurfural which, for very obvious reasons is usually abbreviated to HMF, is an organic compound that forms in sugar-containing foods, often as a result of heating.

HMF is relevant to bees because, at high levels, it is toxic for them. Since beekeepers often heat (or use ready-made feed that has been heated during production) sugar-containing syrups or fondants it’s worth being aware of it.

HMF is also relevant to beekeepers as high levels of it in honey are an indication of prolonged heating during storage and preparation or potential adulteration. For this reason there are legal limits on the levels of HMF in honey sold for human consumption.

I suspect beekeepers in the UK who know about HMF – and many may not – probably worry about it unduly. In tropical countries or regions where high fructose corn syrup is used as a bee food then HMF is likely to be of more immediate importance.

Natural occurrence of HMF

Hydroxymethylfurfural is essentially absent from fresh foods. However, in sugar-containing foods, particularly those that are acidic, HMF levels can build up. A chemical process called a Maillard reaction is responsible for HMF formation (there are other reactions that generate HMF as well, including caramelisation) and the reaction works about five times faster for every 10°C rise in temperature.

Therefore processes such as drying or cooking result in elevated HMF levels. The precise amount varies depending upon the foodstuff, the amount of heating and other factors; typical figures are bread 3 – 180 mg/kg, prunes 240 mg/kg, sugarcane syrup 100 – 300 mg/kg and roast coffee 900 mg/kg {{1}}.

All of these foods can be consumed perfectly safely (at least in terms of their HMF content … prunes can have some adverse effects 😉 ).

It should therefore be obvious that the 40 mg/ml limit {{2}} of HMF in honey has nothing to do with its safety for human consumption.

Dietary HMF has been extensively studied as there were concerns it may be carcinogenic for humans. Several studies showed that non-physiological levels and/or prolonged exposure were cytotoxic or inhibited key enzymes in the cell such as DNA polymerase. However, no evidence for in vivo carcinogenic or genotoxic effects have been demonstrated {{3}}.

HMF is currently considered safe and has been shown to have beneficial antioxidant activity, to protect against hypoxic (low oxygen) injury and to counteract the activities of some allergens.

HMF in honey

Readers familiar with the chemistry of honey will be aware that it is often rich in fructose (one of the sugars from which HMF is derived) and is acidic.

Add a little heat and you have near-perfect conditions for the production of HMF.

How much heat?

It’s actually not just heat but a combination of heat and time.

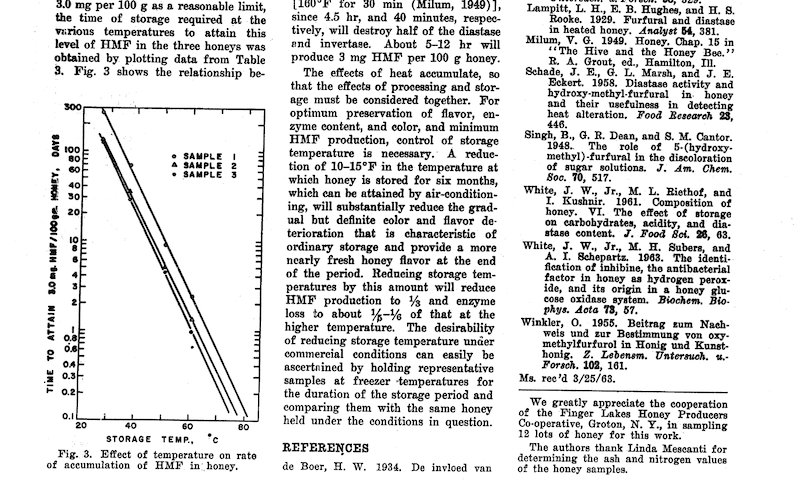

The higher the temperature, the less time is required for the production of a certain amount of HMF. There are several studies of this, but one of the most frequently quoted is from White et al., in 1964 {{4}} which has this slightly skewwhiff, but nevertheless useful, graph of the influence of storage temperature and time on HMF production in honey.

That’s barely legible – check (and enlarge) the original if needed – but the approximate times/temperatures required to generate 30 mg/kg of HMF in honey {{5}} are as follows:

| 30°C | ~250 days |

| 50°C | ~10 days |

| 70°C | ~10 hours |

All of which is good news … heating a 15 kg bucket of rock-solid OSR honey overnight at 50°C to melt it before making soft-set honey is unlikely to significantly increase the HMF levels.

How to avoid the generation of HMF in honey

But, if you are worried about HMF levels, you could always produce creamed honey which just requires overnight warming at 33°C.

This is what I now do; not because of any concern over the HMF levels but because it’s:

- faster

- produces a honey with better batch-to-batch consistency of texture

- generates a jarred honey much less susceptible to frosting

Long-term storage of honey results in the formation of HMF. The lower the temperature it is stored (and the shorter the time) the less HMF is produced. For an exhaustive list of HMF levels quantified in honey stored at different temperatures have a look at Table 1 in Shapla et al., (2018).

It makes senses to store honey in a cool place with a relatively stable temperature.

Quantifying HMF

There are a variety of ways of detecting HMF. Unfortunately, all require laboratory equipment and none are really suitable for home use.

There are spectrophotometric methods – essentially detecting a colour change after adding an indicator that reacts to the presence of HMF – but these can lack both sensitivity and specificity. Some of the chemicals involved are carcinogenic.

More accurate and sensitive are methods use reversed-phase high-performance liquid chromatography. These have been in routine use for years.

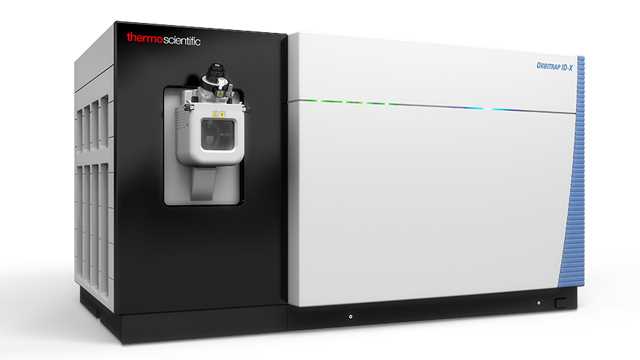

Probably the newest and most advanced methods involve the use of time-of-flight mass spectrometry (MS MALDI-TOF). These ionise the constituents of the sample and measure the time they take to reach a detector. Mass spectrometry is exquisitely sensitive and specific … and the equipment is eye-wateringly expensive.

Since you’re unlikely to have one in your honey processing room {{6}} you’re better off doing your best to avoid conditions that lead to the build-up of HMF in the first place.

OK, enough about honey and humans, what about the bees?

HMF is toxic for both adult bees and developing larvae. The level of toxicity depends upon the concentration of the HMF, the duration of exposure and the developmental stage of the bee.

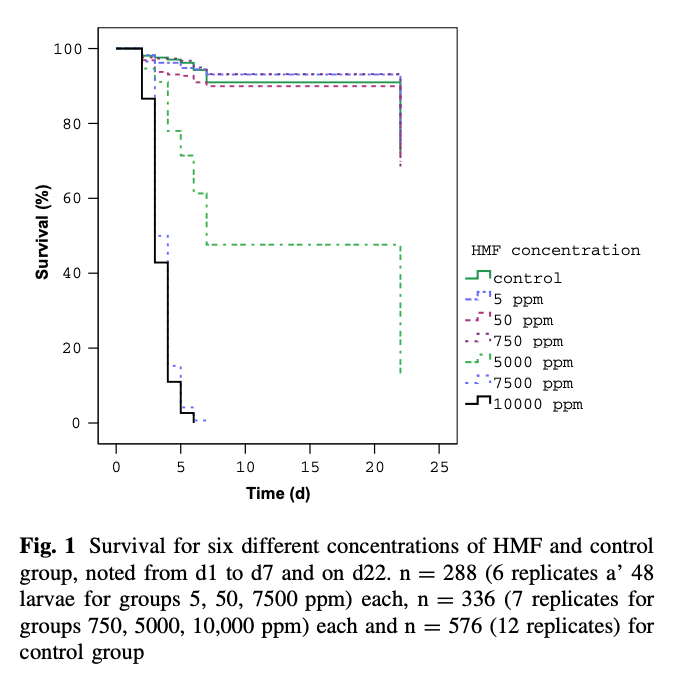

Krainer and colleagues {{7}} looked at toxicity of HMF to developing larvae and showed that concentrations up to 750 ppm (i.e. 750 mg/kg) did not reduce larval or pupal mortality.

They calculated that the LC50 (concentration that produced 50% mortality) at day 7 and day 22 was 4280 ppm and 2424 ppm respectively, with a calculated LD50 (dose per larva that resulted in 50% mortality) of 778 μg and 441 μg at day 7 and day 22 respectively.

Adult bees were less sensitive to HMF in the first week after emergence than during the first week of larval development.

What does all this mean?

It means that high levels of HMF are likely to have a significant impact on adult bees, but – at least until the levels are exceptionally high (grams, not milligrams, per kilogram) will probably not adversely impact brood levels.

Further validation of the adverse effects of HMF to adult bees

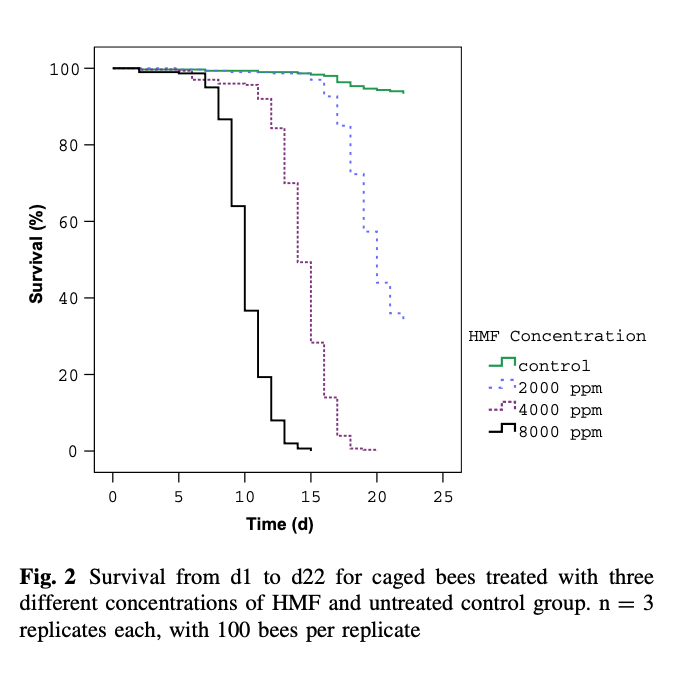

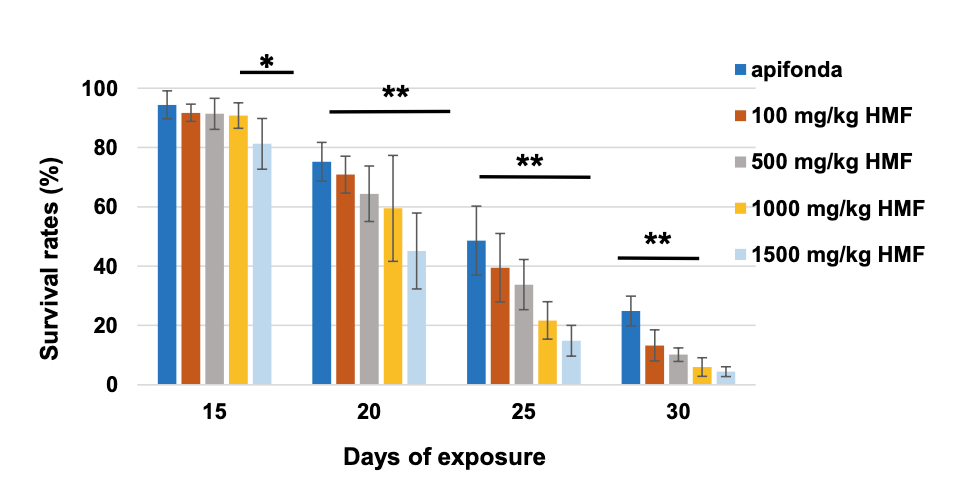

A similar study was recently conducted by Gregorc and colleagues {{8}} using lower concentrations of HMF.

Again, there was a time/dose response, but note that only about 30% of the control bees survived 30 days and this was only double the number that had been fed the lowest level of HMF-spiked Apifonda. Note the clear evidence of a dose-response with increasing levels of HMF in the diet.

Dysentery

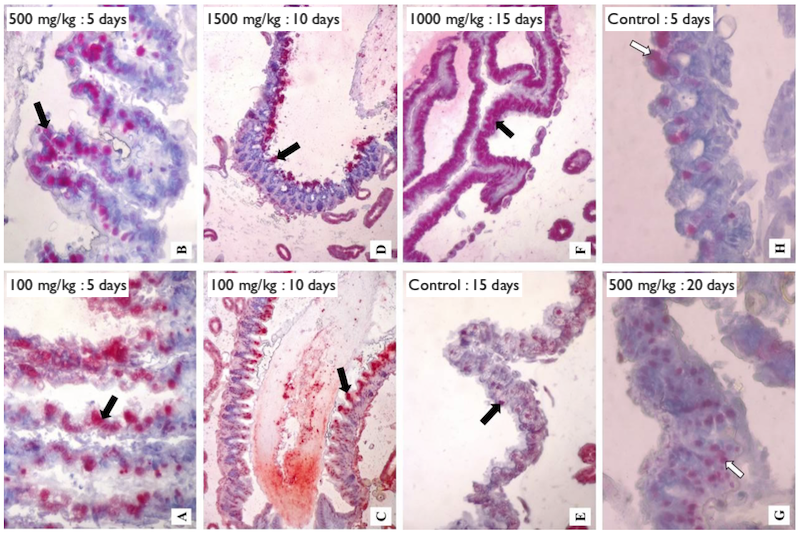

Several studies, dating back at least 50 years, report that high levels of HMF result in dysentery-like symptoms due to ulceration of the gastrointestinal tract of honey bees.

Gregorc and colleagues used immunohistochemistry to investigate the integrity of the gut tissues in the honey bees fed HMF. They stained cells red that were undergoing a process called ‘programmed cell death’ or apoptosis. This is a natural physiological response to damage. The more red staining, the worse the damage.

At higher doses of HMF and/or longer exposure there was increased apoptosis in the gut tissues, presumably accounting for the dysentery-like symptoms often seen (though these were not recorded in this particular study).

Real world beekeeping

All of these bee corpses and fancy-dan immunohistothingamajiggery really just confirm that high levels of HMF are a bad thing™.

In terms of honey processing and storage the allowed levels are nothing to do with human (or bee) health, but everything to do with evidencing overheated, poorly stored or doctored honey.

And since no readers of this blog do these things then there’s no need to be concerned 😉

Assuming your honey starts with low HMF levels (on extraction) then any reasonable levels of heating to liquify honey for filtering, blending or jarring should not result in HMF levels anywhere near to those that would prevent the honey being saleable {{9}}.

Refer to the graph above from the 55 year old paper from White and Co. (shown above) for further validation.

If you’re making thick (2:1 by weight sugar to water) syrup to feed bees perhaps use warm rather than boiling water. However, considering the time involved and the absence of the acidity of honey, even with the latter HMF levels should not get close to high enough levels to endanger the bees.

If you’re making thin (1:1 by weight) syrup then use cold water. Just stir it a bit longer to dissolve it all.

However, take care – or avoid altogether – the use of high fructose corn syrups (HFCS) for feeding bees. I don’t know anyone who does this in the UK and have no experience of it myself. To learn more have a look at this article in Bee Culture. HFCS is high in fructose (the clue is in the name) and acidic, so HMF readily forms.

Studies of commercial HFCS show levels of HMF can start at 30 – 100 mg/kg before any long-term storage.

Oxalic acid

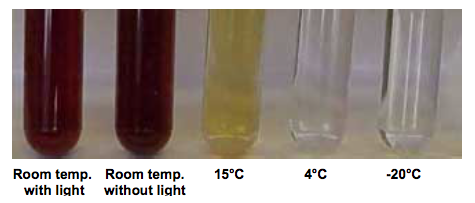

The only time most beekeepers probably need to have concern about HMF levels is in the preparation and storage of oxalic acid solutions for trickle treating colonies in midwinter.

Oxalic acid is, er, acidic. For trickle treating it’s mixed with thin syrup to make a 3.2% solution. The combination of syrup and acidity means that HMF can be produced if stored – for a long time – in unsuitable conditions (under which there is an obvious colour change).

So, if you’re preparing OA solutions for trickle treating either:

- use it immediately and safely dispose of the excess

- store it at 4°C and use then it as soon as possible (before safely disposing the excess)

Fondant

But what about fondant?

The HMF levels in commercially available fondant have recently been discussed on the Beekeeping Forum. I’m grateful to ‘loyal listener reader’ (to use Radio 4’s More or Less definition) Archie McLellan for bringing this to my attention.

The thread started with the challenging title “The truth behind fondants“.

Like all discussion groups, the contributions are many and varied.

Some wander off-topic.

Others use it as an opportunity to get a little dig in at the opposition.

Or a great big dig 😉

Novices and the naive ask simple questions and hope for straightforward answers {{10}}.

Usernames often give no indication of who the poster actually is.

Is the poster a manufacturer or distributor of BeeCentric fondant™ “The best fondant for bees and a whole lot better than that cr*p they sell for ice buns”?

Does the poster use 5 tonnes of fondant a year and buys anything s/he can get as long as it’s cheap enough?

Or does the contributor have a £576,000 Orbitrap MALDI-TOF mass spectrometer in their basement and a damned good idea of exactly how much HMF is present in every commercial source of fondant?

On the internet, nobody knows you’re a dog

Who knows?

I certainly don’t know all of the contributors to these threads.

But I know some of them 😉

Read the thread. It’s now 12 pages long and you’ll do well not to get lost or to disappear down a few cul-de-sacs.

If you’ve ‘got a life’ and want to cut to the chase then have a look at this post in particular.

What do I do?

I use standard Baker’s fondant. It costs about £8-12 for 12.5 kg depending how much you need. I’ve used this type of fondant for a decade for 90% of my colony feeding (and 100% of my autumn feeding).

I’ve never seen any adverse effects from using this type of fondant for my bees.

I simply do not believe some of the negative marketing that is used to promote BeeCentric fondant™ costing £36 for 12.5 kg. It’s not that I can’t afford this {{11}} and it’s certainly not because I don’t care about my bees. I simply choose to trust experience over carefully-worded marketing ‘information’.

To convince me they’d need to publish the HMF levels in their products. They might be lower than bog-standard Baker’s fondant.

And I’d also want to know the HMF levels in standard Baker’s fondant {{12}}.

If they were significantly higher {{13}}, are they anywhere near high enough to damage my bees?

Note

A version of this article appeared in the November 2021 edition of An Beachaire – The Irish Beekeeper.

{{1}}: And in some cases up to 2900 mg/kg.

{{2}}: For completeness I should also add that honey from some tropical countries has higher HMF levels and the limit for these is 80 mg/kg.

{{3}}: Thankfully … I can continue drinking copious cups of coffee while writing these posts.

{{4}}: Effect of Storage and Processing Temperatures on Honey Quality – with thanks to Penn State library who have a scanned copy

{{5}}: White et al., used 3.0 mg/100g as the ‘target’ in their studies and you can’t easily extrapolate to the 40 mg/kg limit that applies to UK honey, but it does provide a good safety margin.

{{6}}: Though we have several at work …

{{7}}: Krainer, S. et al. (2016) ‘Effect of hydroxymethylfurfural (HMF) on mortality of artificially reared honey bee larvae (Apis mellifera carnica)’, Ecotoxicology, 25. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10646-015-1590-x.

{{8}}: Gregorc et al., (2020) Hydroxymethylfurfural Affects Caged Honey Bees (Apis mellifera carnica). Diversity 12: 18 .

{{9}}: Honey that exceed 40 mg/kg HMF can still be sold … but only labelled as Baker’s honey.

{{10}}: Good luck with that.

{{11}}: Though it would hurt paying four times the price.

{{12}}: I’m a scientist … I always need to see the controls.

{{13}}: And, as you can see, I think this is a big ‘if’.

Join the discussion ...