Oxalic acid (Api Bioxal) preparation

This post updates and replaces one published three years ago (which has now been archived). The registered readership of this site has increased >200% since then and so it will be new to the majority of visitors.

It’s also particularly timely.

I will be treating my own colonies with oxalic acid in the next week or so.

Mites and viruses

Varroa levels in the hive must be controlled for successful overwintering of colonies. If you do not control the mites – and by ‘control’ I mean slaughter 😉 – the viruses they transmit to the overwintering bees will limit the chances of the colony surviving.

The most important virus transmitted by Varroa is deformed wing virus (DWV). At high levels, DWV reduces the lifespan of worker bees.

This is irrelevant in late May – there are huge numbers of workers and they’re only going to live for about 6 weeks anyway.

In contrast, reduced longevity is very significant in the winter where more limited numbers of overwintering bees must survive for months to maintain the colony through to the Spring. If these bees die early (e.g. in weeks, not months), the colony will dwindle to a pathetic little cluster and likely freeze to death on a cold winter night.

Game over. You are now an ex-beekeeper 🙁

To protect the overwintering bees you must reduce mite levels in late summer by applying an appropriate miticide. I’ve discussed this at length previously in When to treat? – the most-read post on this site.

I’d argue that the timing of this late summer treatment is the most important decision about Varroa control that a beekeeper has to make.

However, although the time for that decision is now long-gone, there are still important opportunities for mite control in the coming weeks.

In the bleak midwinter

Miticides are not 100% effective. A proportion of the mites will survive this late summer treatment {{1}}. It’s a percentages game, and the maximum percentage you can hope to kill is 90-95%.

If left unchecked, the surviving mites will replicate in the reducing brood reared between October and the beginning of the following year. That means that your colony will potentially contain more mites in January than it did at the end of the late summer treatment.

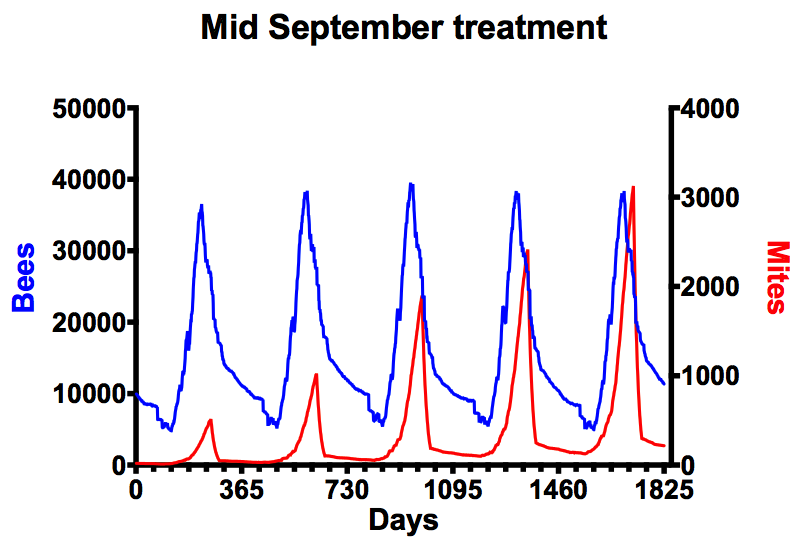

Over several years this is a recipe for disaster. The graph above shows modelled data that indicates the consequences of only treating in late summer. Look at the mite levels (in red, right hand vertical axis) that increase year upon year.

The National Bee Unit states that if mite levels exceed 1000 then immediate treatment is needed to protect the colony. In the modelled data above that’s in the second year {{2}}.

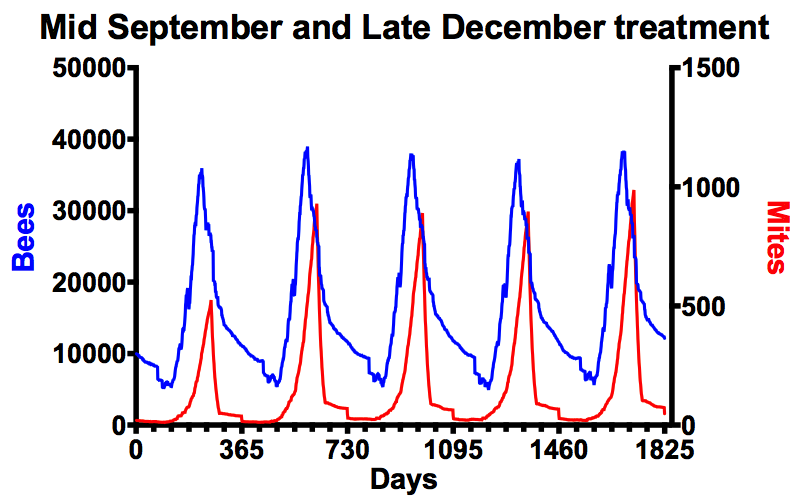

In contrast, here is what happens when you also treat in “midwinter” (I’ll discuss what “midwinter” means shortly).

Mite numbers remain below 1000. This is what you are aiming for.

For the moment ignore the specific timing of the treatment – midwinter, late December etc.

Instead concentrate on the principle that determines when the second treatment should be applied.

During the winter the colony is likely to go through a broodless period {{3}}.

When broodless all the mites in the colony must, by definition, be phoretic.

There’s no brood, so any mites in the colony must be riding around on the backs of workers.

A phoretic mite is an easy mite to kill {{4}}.

A “midwinter” double whammy

A single oxalic acid based treatment applied during the winter broodless period is an ideal way to minimise the mite levels before the start of the following season.

Oxalic acid is easy to administer, relatively inexpensive and well-tolerated by the bees.

The combination – a double whammy – of a late summer treatment with an appropriate miticide and a “midwinter” treatment with oxalic acid should be all that is needed to control mites for the entire season.

However, “midwinter” does not mean midwinter, or shouldn’t.

Historically, winter mite treatments were applied between Christmas and New Year. It’s a convenient time of the year, most beekeepers are on holiday and it’s a good excuse to avoid spending the afternoon scoffing mince pies in front of the TV.

Or with the outlaws inlaws 😉

But by that time of year many colonies will have started brooding again.

With sealed brood, mites have somewhere to hide, so the treatment will be less effective than it might otherwise have been {{5}}.

Why go to all the trouble of treating if it’s going to be less effective than it could be?

The key point is not the timing … it’s the broodlessness of the colony.

If the colony is broodless then it’s an appropriate time to treat. My Fife colonies were broodless this year by mid-October. This is earlier than previous seasons where I usually have waited until the first protracted cold period in the winter – typically the last week in November until the first week in December.

If they remain broodless this week I’ll be treating them. There’s nothing to be gained by waiting.

Oxalic acid (OA) treatment options

In the UK there are several approved oxalic acid-containing treatments. The only one I have experience of is Api-Bioxal, so that’s the only one I’ll discuss.

I also give an overview of the historical method of preparing oxalic acid as it has a bearing on the amount of Api-Bioxal used and will help you (and me) understand the maths.

OA can be delivered by vaporisation (sublimation), or by tricking (dribbling) or spraying a solution of the chemical.

I’ve discussed vaporisation before so won’t rehash things again here.

Trickling has a lot to commend it. It is easy to do, very quick {{6}} and requires almost no specialised equipment, either for delivery or personal protection (safety).

Trickling is what I always recommend for beginners. It’s what I did for years and is a method I still regularly use.

The process for trickling is very straightforward. You simply trickle a specific strength oxalic acid solution in thin syrup over the bees in the hive.

Beekeepers have used oxalic acid for years as a ‘hive cleaner’, as recommended by the BBKA and a range of other official and semi-official organisations. All that changed when Api-Bioxal was licensed for use by the Veterinary Medicines Directorate (VMD).

Oxalic acid and Api-Bioxal, the same but different

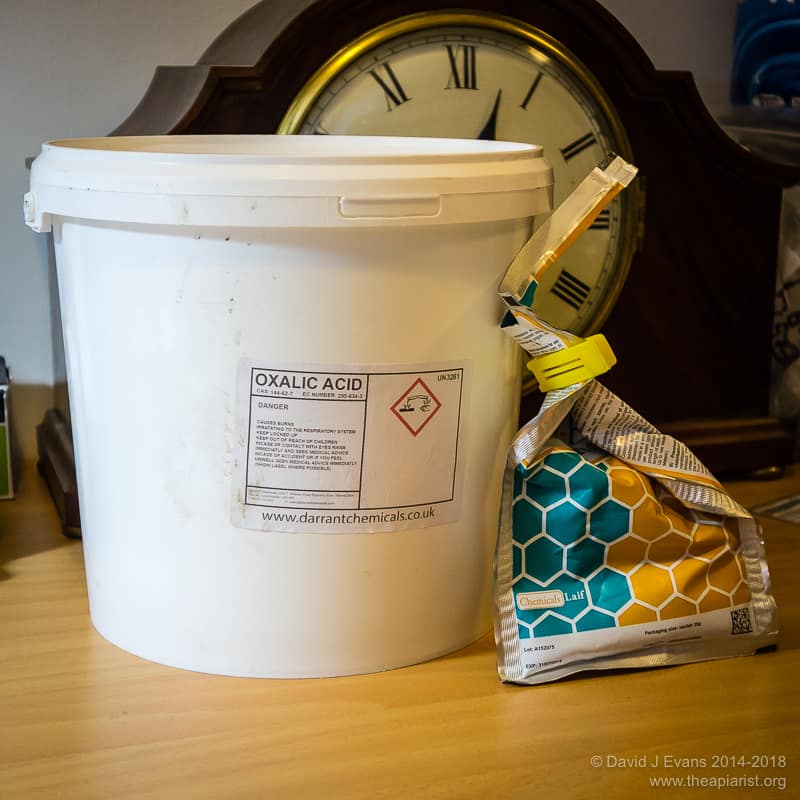

Api-Bioxal is the VMD-approved powdered oxalic acid-containing miticide. It is widely available, relatively inexpensive (when compared to other VMD-approved miticides) and very easy to use.

It’s very expensive when compared to oxalic acid purchased in bulk.

Both work equally well as both contain exactly the same active ingredient.

Oxalic acid.

Api-Bioxal has other stuff in it (meaning the oxalic acid content is a fraction below 90% by weight) and these additives make it much less suitable for sublimation. I’ll return to these additives in a minute or two. These additives make the maths a bit more tricky when preparing small volumes at the correct concentration – this is the purpose of this post.

How much and how strong?

To trickle or dribble oxalic acid-containing solutions you’ll need to prepare it at home, store it appropriately and administer it correctly.

I’ve dealt with how to administer OA by trickling previously. This is all about preparation and storage.

The how much is easy.

You’ll need 5ml of oxalic acid-containing solution per seam of bees. In cold weather the colony will be reasonably well clustered and its likely there will be a maximum of no more than 8 or 9 seams of bees, even in a very strong colony.

Hold on … what’s a seam of bees?

Looking down on the colony from above, a seam of bees is the row visible between the top bars of the frames.

So, for every hive you need 5ml per seam, perhaps 45ml in total … with an extra 10% to cover inevitable spillages. It’s not that expensive, so don’t risk running out.

And the strength?

The recommended concentration to use oxalic acid at in the UK has – for many years – been 3.2% w/v (weight per volume) in 1:1 syrup. This is less concentrated than is recommended in continental Europe (see comments below on Api-Bioxal).

My advice {{7}} – as it’s the only concentration I’ve used – is to stick to 3.2%.

Calculators at the ready!

The oxalic acid in Api Bioxal is actually oxalic acid dihydrate. Almost all the powdered oxalic acid you can buy is oxalic acid dihydrate.

The molecular formula of oxalic acid is C2H2O4. This has a molecular weight of 90.03. The dihydrated form of oxalic acid has the formula C2H2O4.2H2O {{8}} which has a molecular weight of 126.07.

Therefore, in one gram of oxalic acid dihydrate powder (NOT Api Bioxal … I’ll get to Api Bioxal in a minute! Have patience Grasshopper) there is:

90.03/126.07 = 0.714 g of oxalic acid.

Therefore, to make up a 3.2% oxalic acid solution in 1:1 syrup you need to use the following recipe, or scale it up as needed.

- 100 g tap water

- 100 g white granulated sugar

- Mix well

- 7.5 g of oxalic acid dihydrate

The final volume will be 167 ml i.e. sufficient to treat over 30 seams of bees, or between 3 and 4 strong colonies (including the 10% ‘just in case’).

The final concentration is 3.2% w/v oxalic acid …

(7.5 * 0.714)/167 * 100 = 3.2% {{9}}.

Check my maths 😉

Recipe to prepare Api-Bioxal solution for trickling

Warning – the recipe on the side of a packet of Api-Bioxal makes up a much stronger solution of oxalic acid than has historically been used in the UK. Stronger isn’t necessarily better. The recipe provided is 35 g Api-Bioxal to 500 ml of 1:1 syrup. By my calculations this recipe makes sufficient solution at a concentration of 4.4% w/v to treat 11 hives.

There’s an additional complication when preparing an Api-Bioxal solution for trickling. This is because Api-Bioxal contains two additional ingredients – glucose and powdered silica. These cutting agents account for 11.4% of the weight of the Api-Bioxal. The remaining 88.6% is oxalic acid dihydrate.

Using the same logic as above, 1g of Api-Bioxal therefore contains:

(90.03/126.07) * 0.886 = 0.633 g of oxalic acid.

Therefore, to make up 167 ml of a 3.2% Api-Bioxal solution you need to use the following recipe, or scale up/down appropriately:

- 100 g tap water

- 100 g white granulated sugar

- Mix well

- 8.46 g of Api-Bioxal

Again, check my maths … you need to add (7.5 / 0.886 = 8.46) grams of Api-Bioxal as only 88.6% of the Api-Bioxal is oxalic acid dihydrate.

Scaling up and down

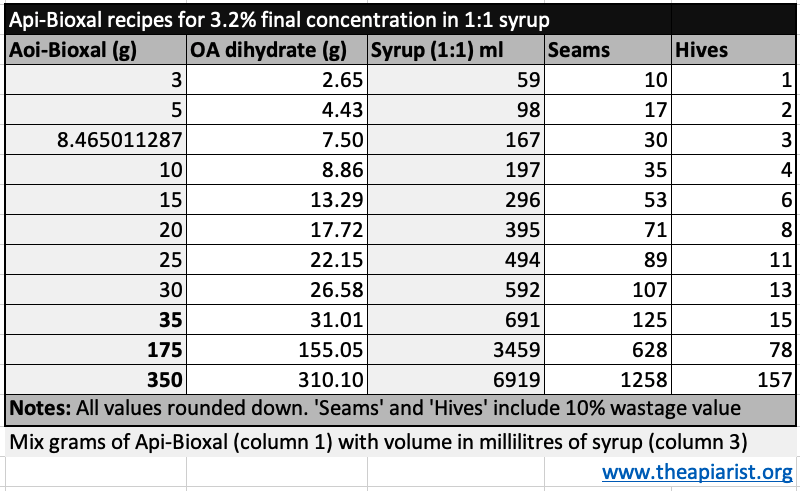

8.46 g is not straightforward to weigh – though see below – and 167 ml may be too much for the number of hives you have. Here’s a handy table showing the amounts of Api-Bioxal to add to 1:1 syrup to make up the amount required.

The Api-Bioxal powder weights shown in bold represent the three packet sizes that can be purchased.

I don’t indicate the amounts of sugar and water to mix to make the syrup up. I’ll leave that as an exercise for the reader … remember that 100 g of sugar and 100 ml of water make 167 ml of 1:1 (w/v) syrup.

Weighing small amounts of Api-Bioxal

The amount of Api-Bioxal used is important. A few grams here or there matter.

If you are making the mix up for a limited number of hives you will have to weigh just a few grams of Api-Bioxal. You cannot do this on standard digital kitchen scales which work in 5 g increments.

Buy a set of these instead.

These cost about a tenner and are perfect to weigh out small amounts {{10}} of Api-Bioxal … or yeast for making pizza dough.

A few words of caution

I don’t want to spoil your fun but please remember to take care when handling or using oxalic acid, either as a powder or when made up as a solution.

Oxalic acid is toxic

- The lethal dose for humans is reported to be between 15 and 30 g. It causes kidney failure due to precipitation of solid calcium oxalate.

- Clean up spills of powder or solution immediately.

- Take care not to inhale the powder.

- Store in a clearly labelled container out of reach of children.

- Wear gloves.

- Do not use containers or utensils you use for food preparation. A well rinsed plastic milk bottle, very clearly labelled, is a good way to store the solution prior to use.

Storage

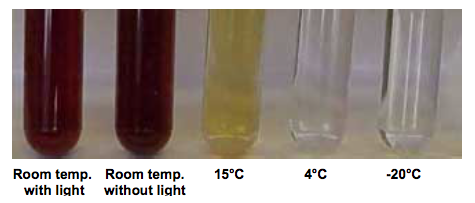

Storage of oxalic acid syrup at ambient temperatures rapidly results in the acid-mediated breakdown of sugars (particularly fructose) to generate hydroxymethylfurfural (HMF). As this happens the colour of the oxalic acid-containing solution darkens significantly.

This breakdown happens whether you use oxalic acid or Api-Bioxal.

HMF is toxic to honey bees at high concentrations. Studies from ~40 years ago showed that HMF concentrations below 30 mg/l were safe, but above 150 mg/l were toxic {{11}}.

At 15°C HMF levels in OA solution can reach 150 mg/l in a little over a week. At room temperature this happens much faster, with HMF levels exceeding 150 mg/l in only 2-3 days. In the dark HMF levels build up slightly less quickly … but only slightly {{12}}.

Therefore only make up OA solutions when you need them.

If you must store your oxalic acid-containing syrup for any length of time it should be in the fridge (4°C). Under these conditions HMF levels should remain well below toxic levels for at least one year. However, don’t store it for this long … use it and discard the excess.

Or prepare excess and share it with colleagues in your beekeeping association.

Don’t use discoloured oxalic acid solutions as they’ve been stored incorrectly and may well harm your bees.

Another final few words of caution

I assume you don’t have a fridge dedicated to beekeeping? That being the case please ensure that the bottle containing stored oxalic acid is labelled clearly and kept well out of the reach of children.

Notes

A quick trawl through the Veterinary Medicines Directorate database turns up several oxalic acid-containing solutions for managing Varroa. These include:

- Oxuvar – approved for trickling or spraying, an aqueous solution of oxalic acid to which you add glucose if you intend to use it for trickling.

- Oxybee – approved for trickling (and possibly other routes, but the paperwork was a minefield!), contains oxalic acid, glycerol and essential oils and is promoted as having a long shelf life.

- VarroMed – approved for trickling, contains oxalic acid and formic acid and can be used throughout the year in one way or another.

I’ve not read the documentation provided with these and so don’t know the precise concentration of oxalic acid they contain. It will be listed as an active ingredient. I have not used these products. As with everything else on this site, I only write about methods or products I am familiar with. I therefore cannot comment on their relative efficacy compared to Api-Bioxal, to Apivar or to careful siting of your hives in relation to ley lines … or 5G phone masts.

{{1}}: This is not necessarily due to resistance, but reflects the fact that not all mites come into contact with the miticide, and of those that do, not all are killed.

{{2}}: Note that the colony was primed with just 20 mites at the beginning of the first season. How many of your colonies have only 20 mites at the beginning of the year?

{{3}}: Not always, and it depends very much upon latitude … and altitude.

{{4}}: Which should perhaps be engraved on the reverse of every hive tool sold to beginners, the front side being of course engraved with the immortal words “Knocking back queen cells is not swarm control”.

{{5}}: Did you not read your hive tool?

{{6}}: Yes, faster than vaporisation, before you ask.

{{7}}: Also see the additional note at the bottom of the page.

{{8}}: Most readers will be able to recognise the H2O at the end, meaning ‘water’. C is carbon, H is hydrogen and O is oxygen. The subscripted numbers indicate the numbers of each atom in the oxalic acid. The 2H2O at the end indicates the di (i.e. two) ‘hydrate’, molecules of water.

{{9}}: Actually 3.206586826347305% but we’ll round it down for convenience

{{10}}: 500 g x 0.01 g

{{11}}: Jachimowich T., El Sherbiny G., Zur Problematik der verwendung von Invertzucker für die Bienenfüttering, Apidologie 6 (1975) 121-143 … unsurprisingly, a paper I’ve not read.

{{12}}: See Bogdanov S., Kilchenman V., Chamere J.D.. Imdorf A. (2001) available online and Prandin, L., Dainese, N. , Girardi, B., Damolin, O., Piro, R., Mutinelli, F. A scientific note on long-term stability of a home-made oxalic acid water sugar solution for controlling varroosis. Apidologie, 32: 451-452.

Join the discussion ...