An Inspector Calls

Hive inspections are the preventative maintenance of the beekeeping year. Conducted properly, they include all the necessary checks to ensure all is well now and will be until the next inspection.

Inspections are an essential part of beekeeping. Beekeepers who don’t conduct inspections probably won’t be beekeepers for long … the colony swarms, goes irretrievably queenless or succumbs to disease.

Or all three 🙁

Actually, there’s another reason … I suspect that beekeepers who don’t regularly inspect colonies are more interested doing something else. They’d prefer to be playing golf or building model railways or potholing. I covered this a few months ago when discussing beekeeping principles and practice.

Their enthusiasm to properly manage their colonies that is, not potholing 😉

Preventative maintenance

The clue is in the name … the purpose of inspections are to maintain the colony in a productive state and to prevent things from happening that might stop this being achieved.

‘Productive’ usually means collecting nectar for honey {{1}}, but could equally well refer to making lots of bees for nucleus colony production. Or, for that matter, maximising drone production to flood the area with good genes for queen mating.

Essentially you’re checking the colony to ensure it’s best able to do what you want it to do.

And, if there are signs that things are going awry, you’re putting in place the preventative measures that help avoid a partial or complete disaster.

A beekeeping “disaster” … let’s keep things in perspective. Swarming, queenlessness, laying workers, robbing, wasps, disease, Varroa infestation, brace comb and all the rest.

Quick or thorough but probably not both

Inspections can either be quick or they can be thorough, but rarely both. The definition of the term ‘inspection’ means “looking narrowly into; careful scrutiny or survey; close or critical examination”.

Therefore, unless you’re only checking one thing, for example whether the queen cells are sealed in a queenright queen rearing colony, it’s likely that the inspection will take some time.

3 day old queen cells …

How long depends upon experience. It probably takes me ~12-15 minutes to go through a box thoroughly and I have a reasonable amount of experience and get quite a bit of practice {{2}}. This is a snail’s pace when compared with commercial beekeepers who can conduct a pretty comprehensive inspection in ~4 minutes.

A beginning beekeeper might take significantly longer than 15 minutes to inspect a colony.

But speed is not the issue.

Why conduct inspections?

The issue – in a routine inspection – is determining the answer to at least the following five key questions (paraphrased from Ted Hooper in his Guide to Bees and Honey):

- Has the colony sufficient room?

- Is the queen present and laying as expected?

- Is the colony building up as expected (early season)? Are there queen cells present (mid season)?

- Are there signs of disease?

- Has the colony sufficient stores?

All of which, done properly, takes a reasonable amount of time.

So that’s the Why? What about when and how should inspections be conducted? These need to be addressed before considering the questions above {{3}}.

When?

There are several ‘when’ questions to be considered. When should you conduct the first inspection of the year? When – as in what sort of day – should you conduct the inspection? How frequently do the inspections need to be conducted?

Unless you’re looking very quickly in a hive for a specific reason inspections should only really be conducted when the exposed brood aren’t going to get chilled. This means you should choose a day when the temperature reaches at least the mid-teens (°C). ‘Shirtsleeve’ weather some call it.

This influences both the timing of the first inspection of the year and – particularly early or late in the season – the time of day that the inspection occurs. On the East coast of Scotland I did my first thorough inspection this year on the 19th of April. Last year – although the winter was nominally shorter and warmer – some hives weren’t inspected until early May because there was never a suitable day.

Lots of hive entrance activity …

Use your own judgement about whether the weather is suitable for early season inspections. The bees should be flying well. This is both an indication that the weather is good enough and reduces the hive population making the condition and amount of brood easier to determine.

Don’t base your decision to inspect on reports you read on beekeeping discussion forums (fora?) about others with their hives bulging with brood. They may be beekeeping in a warmer part of the country. They might be in a different country altogether. It’s also worth remembering that there’s a well-documented tendency – as with online reviews – for contributors to over-exaggerate the positives (and negatives) {{4}}.

I also wouldn’t bother inspecting on an unseasonably warm day very early in the year. It’s unlikely you’ll be able to deduce a whole lot about the state of the colony.

I’ve started, so I’ll finish …

The frequency of inspections is largely dictated by the development time of a queen bee, and to a lesser extent by the strength of nectar flow in your locality.

If a colony is going to swarm they first prepare one or several queen cells. These are capped around day 9 after the egg is laid. Once there are capped queen cells and suitable weather the colony is likely to swarm.

That means you need to inspect more frequently than every 9 days during the peak swarming period of the season – in Fife that’s an ~8 week period from early May late June. In warmer regions, or in years with atypical weather, regular inspections might have to start earlier and continue later.

“Around 9 days” really means anything from 8 days, so a 7 day inspection cycle makes most sense. If a careful inspection one week fails to find evidence of queen cells being developed there’s no chance the colony can swarm for a further 7 days at least (because there are no queen cells that are sufficiently developed).

“fails to find evidence” means you have to inspect carefully. A small charged queen cup, with a day old larva and a bed of Royal Jelly will be capped 6 days later … then they’ll be off 🙂

Generally {{5}} a colony with a clipped queen will take a little longer to swarm, allowing intervals between inspections to be extended to up to 10 days.

However, don’t rely on this … I’ve seen them (er, mine) swarm earlier than this. Inevitably it’s you’re strongest colony and best honey producer 🙁

Relax, but don’t be complacent

Once the peak swarming season is over the frequency of inspections can be reduced. I’m usually on a two-week cycle by mid-July, with most colonies getting their last inspection in mid/late August. This coincides with the optimum time to start applying Varroa treatments to minimise exposure of winter bees to deformed wing virus.

However, remember that a strong colony can fill a super very quickly during a good nectar flow. Inspections are required to ensure the colony has enough space – for brood expansion and for stores.

How to inspect

We’re running out of space … I’ll deal with this in more detail in a future post (and link to it from here).

Essentially, because the goal is to check the state of the colony, you need to ensure that the inspection is conducted in a way that best allows you to determine this.

An agitated colony or one stirred up to be highly defensive makes inspections much harder. It’s therefore important to be as gentle as possible, to be calm and measured in your movements and to avoid jarring the colony.

Use the minimal amount of smoke possible, don’t wave your hands over the top of the frames and don’t crush bees.

And if it all goes pear-shaped, if despite your best efforts the colony gets really stroppy, if you kick a frame over on the ground, drop your hive tool into the open brood box or the smoker goes out at a critical moment {{6}} … close up the box and try again another day.

Colophon

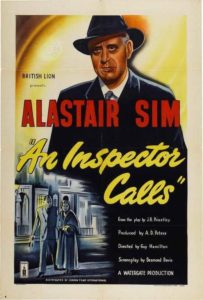

An Inspector Calls is a play by J.B. Priestley. Set in 1912 and first performed in the mid-1940’s, it involves a man – calling himself Inspector Goole – questioning a well-to-do family about the suicide of a working class woman, Eva Smith. Over three acts it is clear that, independently, all in the family are responsible for her exploitation, abandonment, social ruin and eventual death through poisoning. “Inspector Goole” leaves, but the secrets are now out. Subsequent checks with the police and the infirmary show there is no “Inspector Goole” or recent suicides. The play ends with a phone call from the police about the suspicious death of a young woman by poisoning …

Alistair Sim starred in the 1954 film version of the play, where the surname of the lead character was changed from Goole to Poole.

{{1}}: Unless otherwise specified any comments I make assume the colony is being used for honey production.

{{2}}: Over the course of a season I probably inspect 200-400 colonies, with perhaps the same number of ‘quick checks’.

{{3}}: I’ll be dealing with the five questions and a couple of additional ones of my own – hence the at least prefix – in a future post. There isn’t going to be enough space here.

{{4}}: How many times have you read of colonies being opened to find 8 frames of brood in mid-March, or devastating winter losses despite rigorous Varroa management … or no winter losses ever? I’m not saying these things don’t happen, but they do represent what statisticians would consider as ‘outliers‘ in a normal distribution of experience.

{{5}}: Remembering that there are very few hard and fast rules in beekeeping – other than that you will run out of supers during the peak nectar flow – perhaps this should have started ‘more often then not’.

{{6}}: Been there, done all that … and more.

Join the discussion ...