Kick 'em when they're down

Why bother treating colonies in midwinter to reduce Varroa infestation? After all, you probably treated them with Apiguard or Apivar (or possibly even Apistan) in late summer or early autumn.

Is there any need to treat again in midwinter?

Yes. To cut a long story short, there are basically two reasons why a midwinter mite treatment almost always makes sense:

- Mites will be present. In addition, they’ll be present at a level higher than the minimum level achievable, particularly if you last treated your colonies in late summer, rather than early autumn.

- The majority of mites will be phoretic, rather than hiding away in sealed brood. They’re therefore easy to target.

I’ll deal with these in reverse order …

Know your enemy

The ectoparasite Varroa feeds on honey bee pupae and, while doing so, transmits viruses (in particular DWV) that can completely mess up the development of the adult bee. Varroa cannot replicate anywhere other than on developing pupae. It’s replication cycle, and the resulting mite levels in the colony, are therefore tightly linked to the numbers and availability of hosts … honey bee pupae.

If developing brood is available the mite can replicate. Under these conditions, newly emerged adult, mated, female Varroa spend a few days as phoretic mites, riding around the colony on young bees. They then select a cell with a late-stage larvae in, enter the cell and wait until pupation occurs. If developing worker brood is available each infested cell produces 1 – 2 new mites (drone cells produce 3+) and mite numbers increase very rapidly in the colony.

In contrast, if there’s no developing brood available, the mites have to hang around waiting for brood to become available. They do this as phoretic mites and can remain like this for weeks or months if necessary.

Therefore, when brood is in abundance and the queen in laying freely mites can replicate to very high levels. In contrast, when brood is limiting and the queen has reduced her egg laying to a v e r y s l o w r a t e the mite cannot replicate and must be predominantly phoretic.

When does this happen?

Lay Lady Lay … or don’t

Ambient temperature, day length and the availability of nectar and pollen likely influence whether the queen lays eggs. When it’s cold, dark and there’s little or no pollen or nectar coming into the hive the queen slows down, or even stops, laying eggs.

About 8 days after she stops laying there will be no more unsealed brood in the colony. About 13 days after that all the sealed brood will have emerged (along with any Varroa). Therefore, after an extended cold period in midwinter, the colony will have the lowest level of sealed brood … and the highest proportion of the mite population will be phoretic.

Under normal (midsummer) circumstances about 10% of the mite population is phoretic. It’s probably unnecessary to state that, if there’s no brood available, 100% of the mites must be phoretic.

All licensed miticides work extremely well against phoretic mites†.

Caveats, guesstimates, global warming and the Gulf Stream

Whatever the cause, the globe is warming (irrespective of what Donald Trump tweets). Long, hard winters are getting less common (or perhaps even rarer, as they were never particularly common in the UK). In Central, Southern or Eastern Britain it’s possible that the colony will have some brood present all year. In parts of the West, warmed by the Gulf Stream, I’d be surprised if a colony was ever broodless. Only in the North is it likely that there will be a brood break in midwinter.

Most of the paragraph above is semi-informed guesswork. I don’t think anyone has systematically analysed colonies in the winter for the presence of sealed brood. Sure, many (including me) have opened colonies for a quick peek. Others will have peered intently at the Varroa board to search for shredded wax cappings that indicate emerging brood. The presence of brood will vary according to environmental conditions and the genetics of the bees, so it’s not possible to be dogmatic about these things.

However, it’s safe to say that in midwinter, sealed brood – within which the mites can escape decimation by miticides – is at a minimal level.

Reducing mite levels and minimal mite levels

Within reason, the earlier you apply late summer miticides, the better you protect the all-important overwintering bees from the ravages of viruses, particularly deformed wing virus. This is explained in excruciating detail in a previous post, so I won’t repeat the text here.

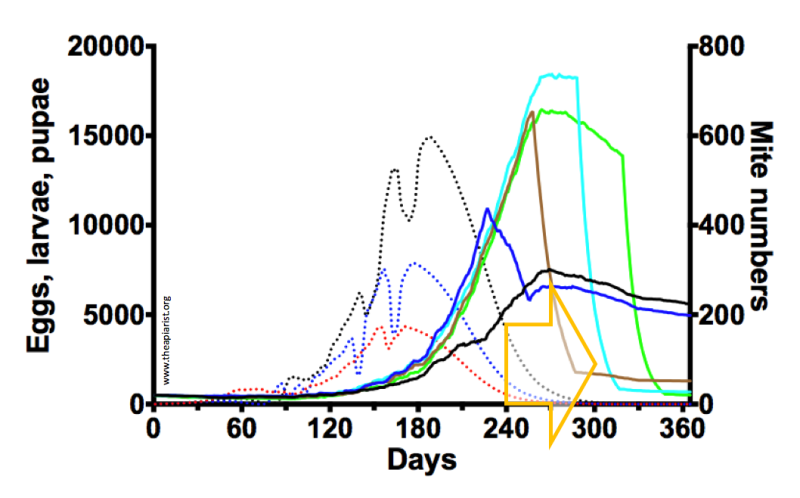

However, I will re-present the graph that illustrates the modelled (using BEEHAVE) mite levels‡.

The gold arrow (days 240-300 i.e. September and October) indicates when the winter bees are being reared. These are the bees that need to be protected from mites (and their viruses). Mite numbers (starting with just 20 in the hive on day zero) are indicated by the solid coloured lines. The blue, black, red, cyan and green lines indicate modelled mite numbers when the colony is treated with a miticide (95% effective) in mid-July, August, September, October or November respectively.

The earlier you treat, the lower the mite levels are when the winter bees are being reared. Study the blue and black lines.

This is a good thing.

In contrast, by treating very late (the cyan and green lines) the highest mite numbers of the season occur at the same time as the winter bees are being reared. A bad thing.

But … look also at mite numbers after treatment

Look carefully at the mite numbers predicted to remain at the end of the year. Early treatment leaves higher mite levels at the start of the following year.

This is simply because mites escaping the treatment at the end of summer have had an opportunity to reproduce during the late autumn.

This is why the additional midwinter treatment is beneficial … it kills residual mites and gives the colony the best start to the new calendar year§.

Kick ’em when they’re down

Early treatment protects winter bees but risks exposing bees the following season to unnecessarily high mite numbers. However, in midwinter, these residual mites are much more likely to be phoretic due to a lack of brood in the colony. As I stated earlier, phoretic mites are relatively easy to target with miticides.

So, give the mites a hammering in late summer with an appropriate and effective miticide and then give those that remain another dose of the medicine in midwinter¶.

But not another dose of the same medicine

Since the majority of mites in a colony with little or no brood will be phoretic, you can easily reduce their numbers using a single treatment containing oxalic acid. This can be administered by sublimation (vaporisation) or by trickling (dribbling).

There’s no need to use any treatment that needs to applied for a month. Indeed, many (Apiguard etc.) are not recommended for use in winter because they work far less well on a largely inactive colony.

I’ve discussed sublimation previously. However, since this requires relatively expensive (£30 – £300) specialised delivery and personal protection equipment it may be inappropriate for the two hive owner. In contrast, trickling requires almost no expensive or special equipment and – reassuringly – has been successfully practised by UK beekeepers for many years. I did it for years before I bought my Sublimox vaporiser.

Therefore, in two further articles this autumn (well before you’ll need to treat your own colonies) I’ll describe the preparation and storage of oxalic acid solutions and its use.

Be prepared

If you want to be prepared you’ll need to beg, borrow or steal the following – sufficient oxalic acid (or Api-Bioxal), a Trickle 2 bottle sold by Thorne’s, a cheap vacuum flask (check your local supermarket … they can be as cheap as £2.50), granulated sugar and a pair of thin disposable gloves.

Do this soon. Don’t leave it until midwinter. You need to be ready to treat as soon as there’s a protracted cold spell (when brood will be at a minimum). Over the last few years my records show that this has been anywhere between the third week in November and the third week in January.

More soon …

† Only MAQS is effective against mites sealed in cells. This is why most miticides are used for extended periods in the late summer or early autumn … the miticide must be present as Varroa emerge from sealed cells.

‡ I’ll repeat the caveat that this is an in silico simulation of what happens in a beehive. Undoubtedly it’s not perfect, but it serves to illustrate the point well. It’s freely available, runs on PC and Mac computers, and is reasonably well-documented. In the simulations shown here the virtual colony was ‘primed’ with 20 mites at the beginning of the year. BEEHAVE was run using all the default settings – climate, forage etc. – with the additional application of a miticide (95% effective) in the middle of the months indicated. Full details of the modelling have already been posted.

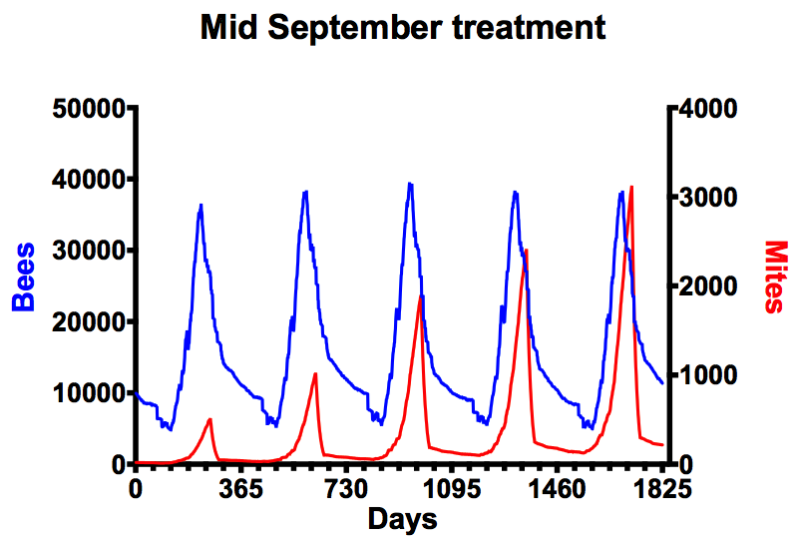

§ The National Bee Unit recommend Varroa levels are maintained below 1000 throughout the season. Without treatment, 20 mites at the start of the season can easily replicate to ~750 in the autumn. If you start the season with 200 mites then levels are predicted to reach ~5000 in the following summer. The colony will almost certainly die that season or the next. There’s a more detailed account of the consequence of winter brood rearing and the level of mite infestation written by Eric McArthur and reproduced on the Montgomeryshire BKA website (no longer online, apologies) that’s worth reading.

¶ The cumulative (year upon year) effect of late summer treatment with no midwinter treatment has been discussed previously. I’ll simply re-post the relevant figure here – 5 years of bee (in blue, left axis) and mite (in red, right axis) numbers with only one treatment per season applied in late September. Within two years the higher mite numbers that are present at the start of the year reproduce to dangerously high levels.

Join the discussion ...