Lime time

Synopsis : Lime, linden, basswood … a fickle source of excellent honey and a potential bee killer. When and why does the lime yield well and what explains the association of some trees with dead bees?

Introduction

There’s an early 20th Century faux castle near me with extensive ornamental gardens. These gardens – or, more accurately, the gardeners – are almost certainly responsible for the introduction of Rhododendron ponticum to the area. This is an invasive species and has spread east with the prevailing wind, blighting the environment, choking the life out of the near-unique temperate rainforest and providing me with an almost unlimited supply of firewood.

Rhododendron provide no nectar or pollen for honey bees in the UK, but are famous as the source of mad honey in Nepal. The local bumble bees do visit it, but I don’t remember seeing a honey bee on the flowers.

However, on a more positive note {{1}} those same gardeners also planted a row of lime trees along the road which are now a stately 30-40 metres high, in full flower and which can sometimes provide an excellent source of summer nectar.

Early on a calm July morning you can hear the insects buzzing in the canopy from at least 75 metres away … not just honey bees, but bumbles, wasps, flies, moths, butterflies and all sorts of other things as well. If we had hummingbirds here (we don’t) they’d probably visit the lime when it’s in flower.

The name ‘lime’ is derived from the Old English lind which originally referred to the lime tree, but you’ll also often find in Middle English poetry {{2}} to mean any tree.

Lime trees (Tilia sp.) are also often called lindens (in continental Europe) and basswood (in the US), but are unrelated to the citrus that produces lime fruit.

Lime species

There are three native or hybrid species of lime in the UK and a handful of other imported ‘exotics’, most of which I’m going to ignore (and which are only usually found in ornamental gardens):

- Broad-leaved lime (Tilia platyphyllos), is a native European tree but very scarce in the UK.

- Small-leaved lime (Tilia cordata), also native to the UK – but probably not as far North as Scotland – and mainland Europe. There’s an interesting BBC podcast on the native small-leaved lime that’s worth a listen.

- Common lime (Tilia x europaea or Tilia x vulgare) which is a natural hybrid of the broad- and small-leaved lime, occurring naturally and also widely planted in parks, gardens and often in urban environments.

To confuse matters further, some clones of common lime are fertile and can therefore further hybridise with other limes. They can therefore produce in a real melange of slightly different forms making precise identification tricky.

I’m pretty certain the trees near me are common limes. They are big trees; being a hybrid the trees grow rapidly and reach a larger overall size than the other species. They also have characteristic dense shoots at the base and middle of the tree, often making the trunk difficult to distinguish.

Not that the precise identification really matters … all of the above, and hybrids thereof, flower when the conditions are right and provide nectar and pollen that our bees can use.

Flowering period

I usually expect to see the lime flowering in early to mid-July. Looking back through my collection of photos, almost all of those of flowering limes were taken in the first 7-10 days of July. This probably means they started flowering at the end of June or very early in July, but I only belatedly realised they were flowering later {{3}}.

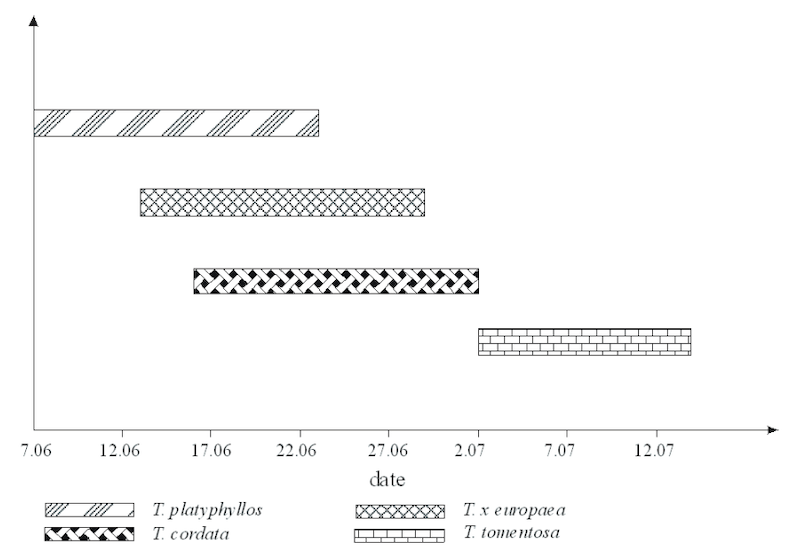

The books claim that the broad-leaved lime flowers in June, with the others starting in July. The only scientific study I could find on this was of lime in Lublin, Poland, where the flowering (of all three species) appears to be 2-3 weeks earlier than it is in the UK.

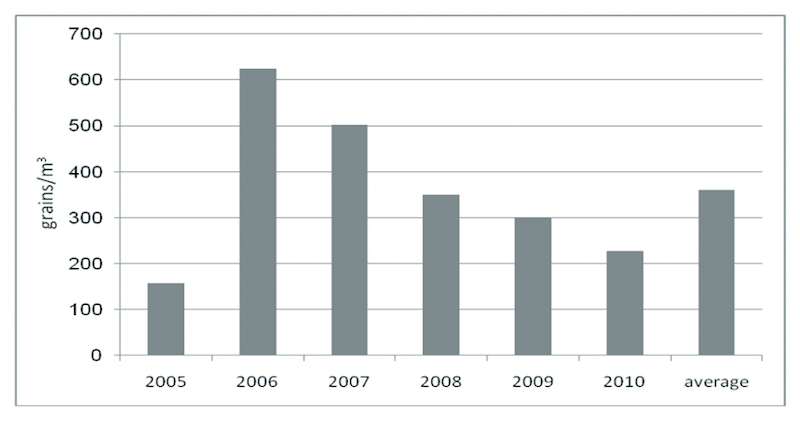

Lime pollen is quite distinctive and its presence in environmental (air) samples over time has been used to determine the duration and peak of the lime flowering period. The majority is produced over a three week period, with the date of peak production varying by as much as a fortnight from year to year. In addition, there was considerable variation between years on the total amount of pollen produced, with ‘poor’ years producing ~25% or less than in the ‘best’ years..

In heavily treed areas it is obvious that it is only the sun-exposed parts of the lime that produce flowers. The crown of the tree in the first photograph had abundant flowers and was alive with pollinators, but the lower branches were almost devoid of the characteristic cymes (the technical term for the flowers on individual stalks) and the umbrella-like bracts which may have evolved to prevent nectar and pollen being washed away by rain.

Flowers and nectar

The common lime produces the most profuse flowers, ~30,000, which is about three times the amount produced by the broad- or small-leaved lime (Jacquemart et al., 2018). These figures were per cubic metre of tree. Remember that the hybrid common lime often forms a significantly larger tree, so a large one at the peak of the flowering season will produce a massive amount of flowers … explaining my ability to ‘hear’ the tree from down the hill on a calm morning.

I specifically say ‘morning’ because nectar production tails off during the day and is at its highest in the morning.

Although the common lime might produce more flowers, it produces only half the amount of nectar per flower than the small-leaved lime. On average, each flower of common lime produces 0.75 μl of nectar. One microlitre is one millionth of a litre, so a large tree bearing 30,000 flowers per cubic metre is going to be producing litres of nectar at any one time.

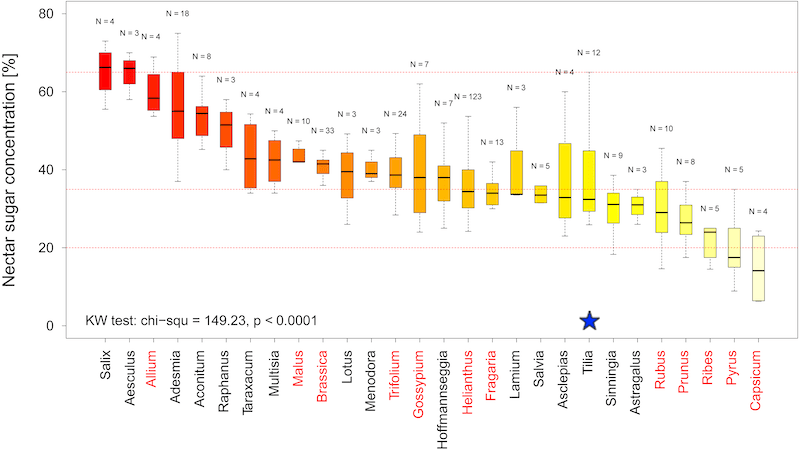

The sheer volume of flowers, coupled with their accessibility and that of the nectar (no long tongues needed here), more than compensates for the relatively low sugar content of lime nectar (~35%).

Rain

In reading half a dozen scientific papers on Tilia I didn’t see a single reference to rainfall linked with comments on nectar production and/or flowering of lime trees.

Which is a bit odd because almost every beekeeper who claims to know anything about lime will say something like ’they need a bit of rain to yield well’ …

For example, yesterday morning my friends at Kilbarchan and District BKA posted the Tweet above.

Which, considering the weather we’ve had recently, made me think … how much rain is needed and when is it needed for lime to yield well?

All of the figures I’ve quoted above make no reference to the climatic conditions in the days and weeks preceding the measurements being taken.

Was 2005 a particularly dry season in Lublin?

Did the rain arrive at just the right time in 2006 for the pollen count (and therefore the flowers that produced the pollen and, presumably, the nectar that attracts the pollinators to the flower) to be so high?

If so, when was ‘just the right time’?

I checked Hooper’s Guide to Bees and Honey which barely mentions lime. Hooper claims he’d seen no good crops of lime honey since the 1930’s. Manley’s Honey Farming only has a couple of sentences on lime. Both, directly or indirectly, suggest that lime isn’t a dependable nectar source.

I don’t have an extensive library of beekeeping books, and have relatively few older books, so there may well be something published I’m totally unaware of that explains the need for 100 mm of rain in the 3 weeks before the onset of flowering.

Or is the entire ’lime needs rain’ thing a convoluted excuse dreamt up by beekeepers to explain the lack of a good summer honey crop?

Rain this season

Late May and the first three weeks of June this year were dry and hot on the west coast. I know the lime are flowering and that the trees are hoachin with pollinators, including my bees. Perhaps the conditions have been ideal?

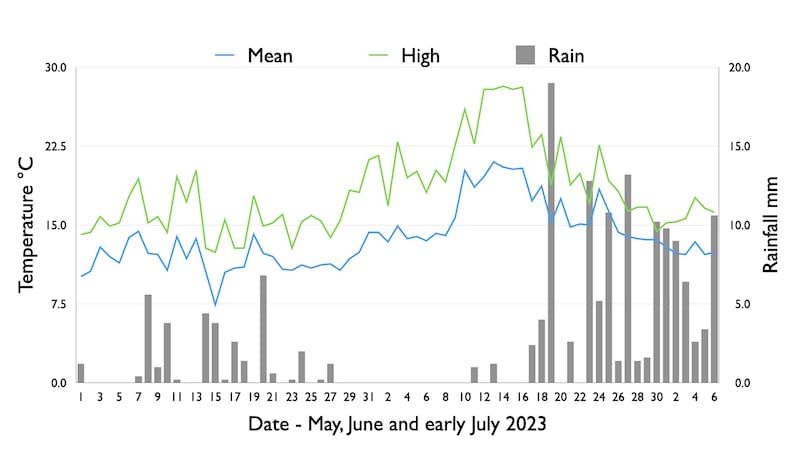

Here, for reference as much an anything else, are graphs of the rainfall and mean and maximum temperature since the 1st of May (or do I need to go further back?).

Unfortunately it’s unlikely to be a bonanza lime honey crop here on the west coast. Firstly I think there are too few trees and, being in a heavily wooded area, only the canopy really flowers well. Secondly it’s been 12°C most of today and raining hard 🙁 .

Lime honey

Lime honey is considered a premium honey … at least by me {{4}}. It’s a clear, runny honey, and is often a light golden colour. Darker lime honey almost certainly also contains honeydew derived from the aphids that are busy feasting on the lime trees.

The honey often has a faint greenish tinge when freshly extracted and jarred.

You’ll read all sorts of descriptions of the aroma of lime honey … I looked up a few online and they read like a contribution to Private Eye’s Pseuds corner.

woody, pharmacy and fresh

mint, balsamic, menthol and camphor

sweet violets

mouth-watering citrus fruit flavour and tantalising notes of fresh mint

The one word I most associate with the flavour of lime honey is zesty. To my jaded palate it tastes deliciously fresh and not too sweet.

In my experience it sells very well, with lots of repeat orders … ’could I have another half dozen jars of that last batch?’

But, unfortunately, in agreement with Hooper and Manley, it does seem far from dependable. Over the last 15 years I think I’ve only had three or four seasons where the lime has yielded well enough to generate significant amounts of essentially monofloral lime honey, though I’m sure it features most years in the mixed summer blossom honey {{5}}.

This variation must be environmental as the trees are a fixture, in contrast to crops like OSR or field beans which vary from year to year.

Of course, being environmental, there’s nothing much I can do to change the temperature, rainfall or humidity … but it would be good to understand what is needed to create a great season for lime honey.

Lime trees and bee deaths

Lime, particularly non-native species and the hybrid common lime, are often planted in towns and cities. They are relatively resistant to pollution and – other than the drip, drip, drip of honeydew – well suited to an urban environment.

There are numerous reports of dead bees – both honey bees and bumble bees – underneath flowering lime trees. These go back centuries (Koch and Stevenson, 2017 cite Bock, H Kreüter buch from 1551 which I can neither source or read 😉 ) and includes an article in Bee World by Eva Crane (1977) that attributes these deaths to mannose sugars in lime nectar.

The species most often associated with bee deaths is the silver lime (Tilia tomentosa), native to south-eastern Europe and south-western Asia, but which is grown as ornamental tree in the UK.

The previously cited Koch and Stevenson (2017) consider five potential causes of these bee deaths:

- Toxic metabolites e.g. mannose or nicotine

- Insecticides

- Natural causes/old age

- Starvation

- Chemical deception

Despite Eve Crane’s assertion that mannose is responsible, several independent scientific analyses of Tilia nectar show it contains no mannose. Since bee deaths date back to Medieval times we can probably rule out insecticides. The natural causes/old age is likely refuted by the age of the corpses, most of which are not decrepit old bees.

The last two potential causes are partially linked.

Most bee deaths are associated with the end of the T. tomentosa flowering period and the suggestion is that the depleted nectar resources leads to starvation. Foragers have depleted sugar reserves and can be ‘rescued’ by being fed Tilia nectar. The chemical deception theory suggests that volatiles in the nectar (e.g. caffeine) cause persistent foraging even after nectar is depleted, again leading to eventual starvation.

Koch and Stevenson (2017) propose that starvation causes these excess bee deaths.

Tilia nectar analysis

A little more recently Jacquemart et al., (2018) conducted a detailed analysis of nectar from T. tomentosa and from the three UK species listed above.

None of the nectars contained detectable levels of mannose or nicotine. I think this pretty much excludes these as the cause of the dead bees seen under lime trees. Bumble bees – which always outnumber honey bees when the corpses are counted – fed either T. tomentosa or T. cordata (small-leaved lime) nectar showed similar levels of survival to controls.

Smell the coffee …

Whilst I think we can rule out toxicity and insecticides as the cause of the bee deaths, I’m not entirely convinced that simple starvation is the cause.

There are other nectars available when the lime is flowering (and going over) – for example, blackberry is looking great at the moment – so you would have to argue that the loss of a major nectar source (probably the largest single nectar source in an urban environment) was associated with a constancy that prevented the switching and exploitation of other nectars.

Constancy is defined as ‘restricting visits to one flower type, even when other rewards are accessible’.

This is where the chemical deception theory originates.

Perhaps there is something in Tilia honey that effectively deceives bees to continue to return to the lime trees after nectar stops being available? {{6}}

One suggestion is that small amounts of caffeine in Tilia honey are responsible.

Coffee and bees deserves a full post of its own … there is evidence that caffeine increases foraging and recruitment, but these studies are on honey bees. I’m not sure similar studies have been conducted on bumble bees which account for 75% of the dead bees.

Finally, to confound the story further, honey and bumble bees differ in their natural (decaffeinated) constancy, with the former showing significantly greater fidelity.

I think our understanding of the association of Tilia foraging and bee deaths remains incomplete. Although largely involving the silver lime, other species have been implicated as well.

In the meantime, I’d just like the weather to improve so that my bees can take advantage of the row of huge flowering limes just down the road …

Notes

Two final thoughts that came to me just before posting …

- lime may not have evolved to ‘deliberately’ (which isn’t how evolution works) deceive bees into elevated constancy and subsequent starvation. The caffeine (or whatever) that deceives bees might be a secondary product of the tree, unrelated to bees and pollination.

- are lime more often associated with bee deaths than other large nectar sources? How many dead bees have been counted in a field of oil seed rape? Lime are often planted in urban environments where, a) they are easily accessed by bee-aware members of the public, and b) the ground under the tree is usually flat and either tarmac or closely mown, rather than dense understorey and ground cover in natural woodland.

References

Crane, E. (1977) On the scientific front. Bee World 58: 129–130 https://doi.org/10.1080/0005772X.1977.11097662. Accessed July 6, 2023.

Jacquemart, A.-L., Moquet, L., Ouvrard, P., Quetin-Leclercq, J., Hérent, M.-F., and Quinet, M. (2018) Tilia trees: toxic or valuable resources for pollinators? Apidologie 49: 538–550 https://doi.org/10.1007/s13592-018-0581-3. Accessed July 4, 2023.

Koch, H., and Stevenson, P.C. (2017) Do linden trees kill bees? Reviewing the causes of bee deaths on silver linden (Tilia tomentosa). Biology Letters 13: 20170484 https://royalsocietypublishing.org/doi/10.1098/rsbl.2017.0484. Accessed July 4, 2023.

Weryszko-Chmielewska, E., and Sadowska, D. (2010) The phenology of flowering and pollen release in four species of linden (Tilia L.). Journal of Apicultural Science 54: 99–108.

{{1}}: Other than the savings on firewood which would otherwise cost me £160 a bag.

{{2}}: If you read Middle English poetry.

{{3}}: I’m a bit slow off the mark sometimes often.

{{4}}: Your preference may be different.

{{5}}: I know there are trees well within foraging range over this period.

{{6}}: Though I’m struggling to think of an evolutionary justification for this.

Join the discussion ...