Location, location, location

Synopsis: Finding a good apiary location involves homework and legwork. What should you look for and what to avoid? A good apiary will ensure your bees are more productive and your beekeeping is much more enjoyable, so finding one is time well invested.

Introduction

It was the writer and diarist John Evelyn (1620 – 1706) who, in 1697, first used the term apiary to mean a place where hives are kept. Apiary also means a bee house {{1}}, but for the purpose of this post I’m going to restrict myself to outdoor locations where bees are kept.

How should you go about finding a good apiary location?

Remember … bees are not pets.

They are working livestock.

That sting.

They are also quite high maintenance.

Despite what some seem to suggest, you cannot just dump them in any old field and return months later to harvest buckets of beautiful honey. For about six months of the year they need regular checks to ensure they have enough space, to prevent them from swarming and to make sure they are healthy.

All of these things – their work needs {{2}}, the maintenance, the stinging – need to be taken into account when deciding where to site your beehives.

Since I’m in the process of finding and setting up a new apiary I thought it might be timely {{3}} to discuss the topic in a little more detail.

The garden … perhaps not the best choice

Many beekeepers keep their bees in their garden.

It’s certainly convenient.

However, as I’ve discussed before, there are a number of disadvantages. If you have a small urban garden you can be certain that ” … whatever the evidence (or lack of it), it will be your bees that sting your neighbours grandchild, poop on their Beemer and swarm onto the garden swing.”

Although I always site bait hives in my garden, until I moved to the remote west coast I’ve never kept bees there permanently {{4}}.

My bees are generally well behaved and my swarm control is reasonably good. However, even the most benign bees can have a bad day, and reasonably good means that there is still room for improvement {{5}}.

It just takes one stung grandchild, one BMW getting the pointillism with poop treatment, or one missed queen cell, to potentially sour relationships forever with your neighbours.

Why risk it?

Yes, it’s convenient {{6}}.

Yes, it’s wonderful to be able to see the bees busily flying in and out.

But disputes with neighbours can get ugly and are cited as the reason for over 350,000 people moving house each year.

Is that a risk worth taking?

The garden … you’ll still need an out apiary

If you do intend to keep bees in the garden, check the deeds to make sure that it’s allowed. Some preclude ‘keeping livestock’ which, from a legal perspective, probably means bees {{7}}.

And, if you do keep bees in your garden, I’d argue you still need an additional, or ‘out’, apiary {{8}}. There are two reasons for this:

- If and when you need to move your bees you will potentially have to do so at very short notice {{9}}. If the colony goes queenless and gets stroppy, or a child develops an anaphylactic reaction, the neighbours are not going to accept being told ”It’ll be OK in 3-4 weeks … and it might not be my bees anyway”. Remember, it’s the summer and they want to have a BBQ.

- Some beekeeping manipulations (like making up nucs for swarm control) are made easier by simply moving bees to a distant site.

For the rest of this post I’m going to focus on the features I look for in an apiary location, largely concentrating on rural or semi-rural areas {{10}}. I’ll focus on the needs of both the bees and the beekeeper, and I’ll include some suggestions to make your searches a little easier.

Food and water

Other than in very specific circumstances {{11}} the area around the apiary must have good forage.

Without ample pollen and nectar being available the colony will not thrive, and they certainly will not collect excess nectar to provide you with a honey crop.

If the intention is to use the apiary year-round then there must be forage available throughout the period of the year when the bees are active.

Of course, the bees will range far and wide to find suitable forage, but the closer they are to it the better they will do.

My hives in this field margin did fantastically well on the oil seed rape (OSR), but they also benefitted from hedgerow flowers and tree pollens, and from ample dandelion, clover and blackberry. Even without the OSR, it was a good spot.

In additional to good forage, bees also need to have access to water. My bees spend hours collecting water from a natural pool a dozen yards from the hives. It is possible to provide water from an artificial source – like a moss-filled bucket in the apiary – but a natural source doesn’t need topping up unless there’s a serious drought.

But don’t site your hives too close to water if there is any risk of flooding.

Hives, particularly poly hives, do float. However, they don’t necessarily float the right way up.

Searching for a new apiary location in midwinter can help exclude some sites where flooding might be an issue.

In contrast, identifying suitable forage in midwinter is more difficult. In my experience the only ways to identify whether an area has suitable year-round forage are to:

- learn what the major forage types are (even when they’re not in flower), and then spend time reconnoitering likely areas {{12}}.

- ask other beekeepers {{13}}.

But where do you start looking?

Near … but not too near

If you are looking for an out apiary i.e. one located some distance from your ‘home’ apiary {{14}} then it makes sense to search at least 3 miles away. This is because, although bees can return to a hive from further away, if their originating hive is moved at least three miles they reorientate to the new location. This means you can make up nucs or move mating hives to the out apiary without the risk of the flying bees returning to their original location.

But, if you are looking for your first apiary, it makes sense to choose an area close enough to home so that travel doesn’t become a big part of your beekeeping. It’s surprising how often you forget things, or how often you just need to nip back to the bees to do something trivial.

Some of my apiaries are 130 miles from home and I write lists of what I need to take with me. Just ‘nipping back’ is not an option … all my colony manipulations have to be completed during scheduled visits.

There’s one more thing to consider when thinking about the general area in which to search for a suitable apiary site … where do other beekeepers keep their bees?

Ask some of the ‘old hands’ in your association. They might not tell you exactly where their bees are, but they are likely to be able to give you some general pointers.

In addition, keep your eyes peeled {{15}} when you are out and about on your travels.

I enjoy walking and it’s surprising the number of field margins, copses and rough land where you can find a few hives tucked away out of plain sight. Take a note of where they are and then start to focus in on areas that might be suitable for you.

Google it

Google and Microsoft both have excellent mapping facilities and these can help you find a suitable location for an apiary.

If you know where your home apiary is and/or the location of other hives in the area, you can plot the potential foraging range of bees from these apiaries, and look for likely looking gaps.

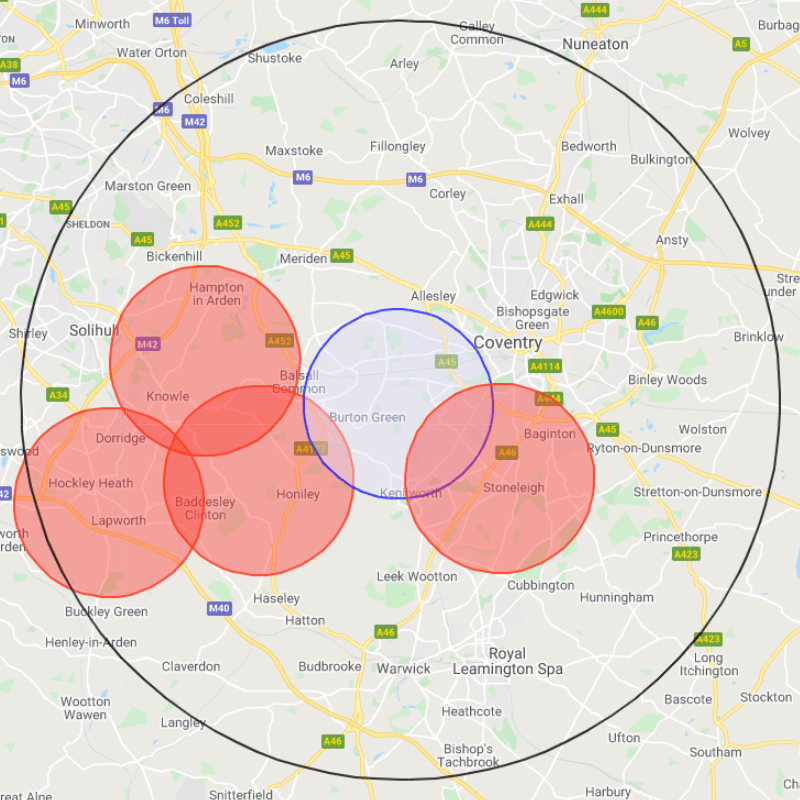

The following example is entirely hypothetical. It’s based upon an apiary of mine (blue circle) in Warwickshire, now vacated. The red circles mark other apiaries and the black circle is the limit beyond which I wasn’t prepared to travel {{16}}.

If you find likely looking gaps in the overlapping circles they might be a good place to start your detailed search for an apiary.

It’s also worth noting that the high resolution satellite images available from Google and Microsoft allow a much more detailed search for suitable apiary sites. This type of online searching cannot replace walking around a few fields, but they might well help you decide which side of the field to start at.

Look for access tracks that fade away to nothing, wide field margins, corners of agricultural land that remain unploughed, large clearings in small woods or copses etc.

Remember, you might have to do this in the ‘off season’ so it’s worth learning to identify likely forage (or at least potential forage) when the area looks a lot less bee-friendly than it would in midseason.

Hi-res can help (you and the bad guys)

And also look for signs that other beekeepers have already placed hives in the area.

In the areas with the highest resolution mapping it is possible to ‘find’ hives that may be invisible from a cursory drive past or walk through an area. It’s worth using both Microsoft and Google maps for these detailed searches as they use different satellite images (and update them relatively frequently) and so details can be visible on one that are invisible on the other.

The photo above shows a few hives in a field on a Google satellite images. The photo below shows the Microsoft image of the same site.

The half dozen hives visible in the first of these two pictures wouldn’t have stopped me looking for a suitable apiary nearby. The fifteen or more additional hives in the lee of the hedge (hidden in shade in the first picture) suggests that the area might be saturated with bees and that I should look elsewhere.

In places, the detail on these satellite images is amazing. Here’s the Google image of my first bee shed within a fenced area also containing half a dozen hives.

Be aware that anyone can view these images and that they therefore potentially pose a security risk {{17}}. If you already have an established apiary check to see how visible it is … you might be surprised (and disappointed).

Boots on the ground

Once you’ve done enough homework it’s time to start visiting a few likely looking locations to see if they might be suitable.

Obviously you should not trespass (and the freedom to roam rights in Scotland are a huge bonus here) but it’s usually quite easy to determine whether an area is a non-starter or has some real promise.

You might need use your imagination. What will it look like on a dry May afternoon, rather than a dreich morning in January?

The site above looked semi-promising on the map. However, the conifers were larger than I’d expected and the site would have been too shaded.

When will the sun first appear? In hilly areas you can calculate when the sun will appear and disappear over the horizon using a combination of this tool to determine the trajectory of the sun and this tool to calculate the horizon.

How good is access? Remember, you might want access late evening or early morning to move hives. If it’s close to the farmhouse/stately home that might not be possible.

And, conversely, how secure is the site likely to be?

Is there safe parking nearby?

Can you drive right up to the (likely spot for the) hives, or will there be carrying involved?

In either case, how soft is the ground? Will you need wellies, a hivebarrow, a Toyota Hilux or a canoe?

Is the area likely to be a frost pocket? If so, look elsewhere.

What is the shelter like in the direction of the prevailing weather?

Is there sufficient space? You might start with just a couple of hives, but if your ambition is to have a dozen this makes additional demands on the space and forage needed.

Time spent in reconnaissance etc.

I try and work out all of the above before I approach the landowner {{18}}.

Rather than asking Can I put some bees on your land?, when the answer might be affirmative but you might be offered an unsuitable location, it’s better to ask ”Can I put some hives in the north-west corner of the field with the large dead oak tree in it?”

You’ve already worked out that access is good and the ground is well drained, you can face the hives in a south easterly direction to get the morning sun, there’s excellent shelter to the west, the site isn’t overlooked and there are no footpaths or bridleways nearby.

By all means justify your choice to the landowner, and consider other locations if offered. However, don’t just accept somewhere without considering all the pros and cons first.

You probably have a much better idea of what your bees need. You certainly have a better idea of what you (as the beekeeper) need. Don’t lose sight of these in your discussions.

A jar or two of honey to sweeten the deal always helps. You should expect to pay a ground rent which you should agree when you start.

Exchange contact details and tell the landowner your vehicle registration so they don’t mistake you for a poacher or flytipper … and congratulate yourself on a job well done.

Final considerations

Most of what I’ve written above largely applies to finding apiary sites in rural areas. That’s because those are the locations I’ve used for 95% of my beekeeping. I’ve never kept bees on an allotment {{19}} and the bees I’ve kept in gardens have been – and still are – in gardens surrounded by open countryside or farmland.

In the latter cases I talked to the landowner first, often after they bought honey from me and then asked whether I was looking for another site for hives. I explain in detail the type of location(s) I’m looking for and then have a guided tour of their land.

If you explain in advance that you want a south-east facing sunny site you can avoid sounding too negative when they offer you a heavily shaded damp corner behind the compost bins {{20}}.

The search for a suitable apiary location can take weeks or months … or you might find it at the very first gateway you stop at.

It’s certainly well worth investing time in finding a suitable site. A well chosen apiary will make your beekeeping a much more enjoyable experience and should make your bees a lot more productive.

{{1}}: See posts I’ve made on bee sheds.

{{2}}: i.e. forage.

{{3}}: And relatively easy to write as it’s at the forefront of my mind …

{{4}}: I do now have bees in my ‘garden’, but it’s not a garden in the conventional sense … it’s just rough hillside and mixed woodland surrounding the house and separating us from the howling wilderness.

{{5}}: Quite a bit of room.

{{6}}: Keeping bees in the garden that is, not souring relationships with your neighbours.

{{7}}: But remember, I’m a beekeeper (just about) not a lawyer, so you might be wise to get a second opinion. However, unlike me, the lawyer will probably charge you (handsomely) for the opinion.

{{8}}: The term ‘out apiary’ is often used to indicate a secondary apiary, distant from your main apiary.

{{9}}: Hours, not days.

{{10}}: But some of the points will be relevant to urban apiaries as well, so keep reading.

{{11}}: These are outside the scope of this post, but I’m really referring here to apiaries set up for queen mating or as quarantine apiaries.

{{12}}: John Marsden’s ”Time spent in reconnaissance is seldom wasted” is particularly relevant here.

{{13}}: And be aware that they might not want the competition.

{{14}}: Even if your ‘home’ apiary isn’t located where your home is located.

{{15}}: i.e. be alert, a phrase that has its origins with Sir Robert Peel, the founder of the first organised British police force in the 1820’s.

{{16}}: In reality, this area of Warwickshire has bees in almost every other field, not least because it’s a pretty good environment for bees and my alma mater association (Warwick and Leamington beekeepers) are very active and have well over 300 members. It was a great area to have a bait hive or three ;-)

{{17}}: I’ve either doctored the images above, or – in the case of the bee shed – used an undoctored image of a shed and apiary that was moved over two years ago. The more up-to-date photos on Bing now just show the shed foundations.

{{18}}: Finding the landowner I’ll leave as an exercise for the reader. If it’s farmland it makes sense to ask at the nearest farmhouse. If it’s in the Capability Brown-sculpted surroundings of a stately home then … good luck with that!

{{19}}: I had trouble enough growing the carrots.

{{20}}: That’s a real example!

Join the discussion ...