Measles, mites and anti-vaxxers

About 11,000 years ago nomadic hunter-gatherers living near the river Tigris discovered they could collect the seeds from wild grasses and, by scattering them around on the bare soil, reduce the distance they had to travel to collect more grain the following year.

This was the start of the agricultural revolution.

They couldn’t do much more than clear the ground of competing ‘weeds’ and throw out handfuls of collected seed. The plough wasn’t invented for a further 6,000 years and wouldn’t have been much use anyway as they had no means of dragging it through the baked-hard soil.

But they could grow enough grains and cereals to settle down, doing less hunting and more gathering. Some grains grew better than others, with ‘ears’ that remained intact when they were picked, making harvesting easier. The neophyte farmers preferentially selected these and, about 10,000 years ago, the first domesticated wheat was produced.

Since they were less nomadic and more dependent upon the annual grain harvest they took increasing care to protect it. They were helped with this by the hunting dogs domesticated from wolves several thousands years earlier. The dogs protected the crops and kept the wild animals, primarily big, cloven-hooved ungulates and the native wild sheep and goats, at a distance.

But those that got too close were trapped and were remarkably good to eat.

And since it was easier to keep animals penned up to avoid the need to actively hunt them it was inevitable that sheep and goats were eventually domesticated (~9,000 years ago) … and the nomadic hunter-gatherers became settled farmers practising recognisably mixed agriculture.

Domestication of cattle

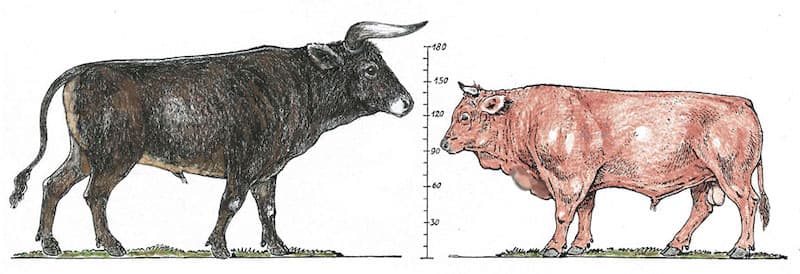

The sheep and goats were a bit weak and scrawny. The large ungulates, the aurochs, gaur, banteng, yak and buffalo {{1}} had a lot more meat on them.

Inevitably, first aurochs (which are now extinct) and then other wild ungulates, were independently domesticated to produce the cattle still farmed today. This process started about 8,000 years ago.

Cattle were great. Not only did they taste good, but they could be managed to produce milk and were strong enough to act as beasts of burden.

The plough was invented and crop yields improved dramatically because the grain germinated better in the cleared, tilled soil. Loosely knit families and groups started to build settled communities in the most fertile regions.

Bigger farms supported more people. Scattered dwellings coalesced and became villages.

Not everyone needed to farm the land. The higher yields (of grain and meat) allowed a division of labour. Some people could help defend the crops from marauders from neighbouring villages, some focused on weaving wool (from the sheep) into textiles while others taught the children the skills they would need as adults.

Communities got larger and villages expanded to form towns.

Zoonotic diseases

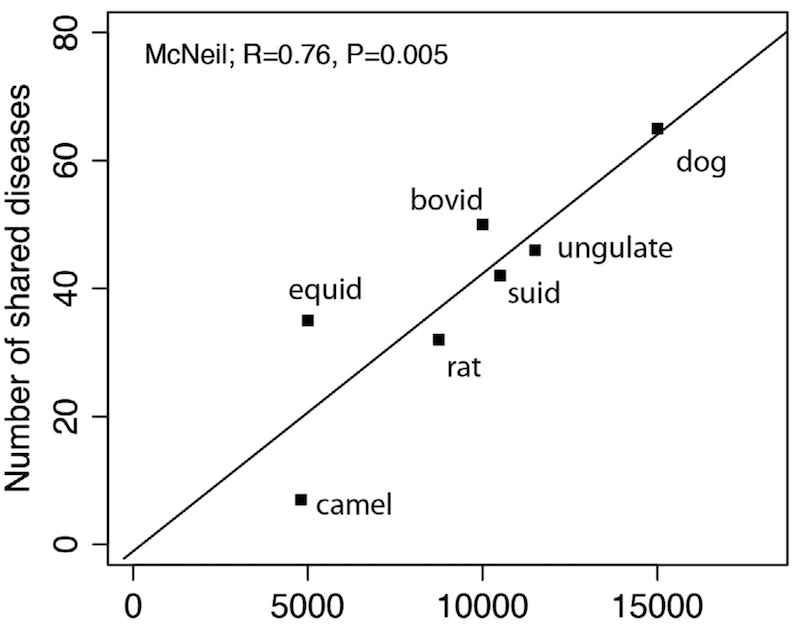

Hunter-gatherers had previously had relatively limited contact with animals {{2}}. In contrast, the domestication of dogs, sheep, goats and cattle put humans in daily contact with animals.

Many of these animals carried diseases that were unknown in the human population. The so-called zoonotic diseases jumped species and infected humans.

There’s a direct relationship between the length of time a species has been domesticated and the number of diseases we share with it.

The emergence of new diseases requires that the pathogen has both the opportunity to jump from one species to another and that the recipient species (humans in this case) transmits the disease effectively from individual to individual.

The nomadic hunter-gatherers had been exposed to many of these diseases as well but, even if they had jumped species, their communities were too small and dispersed to support extensive human-to-human transmission.

Rinderpest and measles

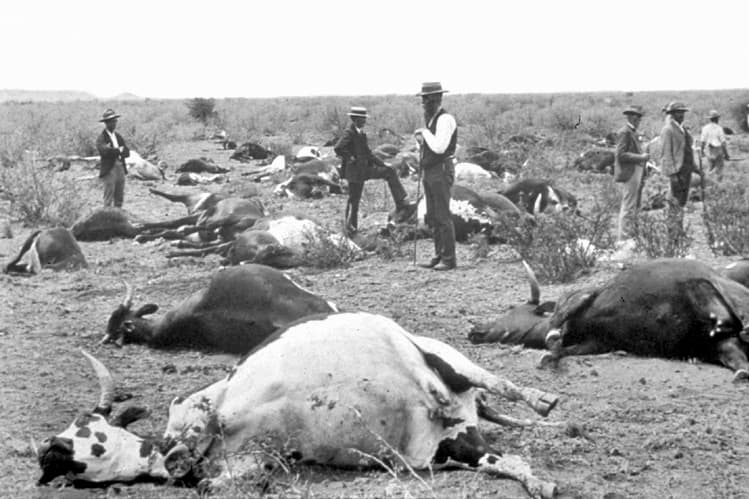

Until relatively recently rinderpest was the scourge of wild and domesticated cattle across much of the globe. Rinderpest is a virus that causes a wide range of severe symptoms in cattle (and wild animals such as warthog, giraffe and antelope) including fever, nasal and eye discharges, diarrhoea and, eventually, death. In naÏve populations the case fatality rate approaches 100%.

Animals that survive infection are protected for life by the resulting immune response.

Rinderpest is closely related to canine distemper virus and measles virus. Virologically they are essentially the same virus that has evolved to be specific for humans (measles), dogs (canine distemper) or cattle (rinderpest).

Measles evolved from rinderpest, probably 1,500 to 2,000 years ago, and became a human disease.

Rinderpest was almost certainly transmitted repeatedly from cattle to humans in the 6,000 years since auroch or banteng were domesticated. However, the virus failed to establish an endemic infection in the human population as the communities were too small.

However, by about 1,500 – 2,000 years ago the largest towns had populations of ~250,000 people. Subsequent studies have demonstrated that you need a population of this size to produce enough naÏve hosts (i.e. babies) a year to maintain the disease within the population.

This is because, like rinderpest, measles induces lifelong immunity in individuals that survive infection.

Measles is a devastating disease in an unprotected community. Case fatality rates of 10-30% or higher are not unusual. It is also highly infectious, spreading very widely in the community {{3}}. Survivors may suffer brain damage or a range of other serious sequelae.

Measles subsequently changed the course of history, being partially responsible (along with smallpox) for Cortés’ defeat of the Aztec empire in the 16th Century.

John Enders, Maurice Hilleman and Andrew Wakefield

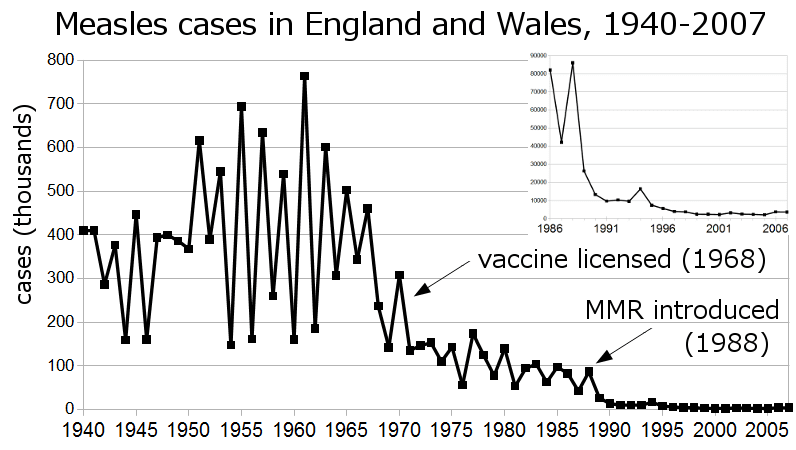

In the late 1950’s John Enders developed an attenuated live measles vaccine. When administered it provided long-lasting protection. It was an excellent vaccine. Maurice Hilleman, in the early 1970’s combined an improved strain of the measles vaccine with vaccines for mumps and rubella to create the MMR vaccine.

Widespread use of the measles and MMR vaccines dramatically reduced the incidence of measles – in the UK from >500,000 cases a year to a few thousand.

If vaccine coverage of 92% of the population is achieved then the disease is eradicated from the community. This is due to so-called ‘herd immunity’ {{4}} in which there are insufficient naÏve individuals for the disease to be maintained in the population.

Measles cases (and deaths) continued to fall everywhere the vaccine was used.

There was a realistic possibility that the vaccines would – like rinderpest {{5}} – allow the global eradication of measles.

And then in 1986 Andrew Wakefield published a paper in the Lancet suggesting a causative link between the MMR vaccine and autism in children.

Subsequent studies showed that this was a deeply flawed and biased study. And totally wrong.

There is not and never was a link between autism and measles vaccination {{6}}. But that didn’t stop a largely uncritical press and subsequently even less critical social media picking up the story and disseminating it widely.

Measles and the anti-vaccine movement

Measles vaccination rates dropped because a subset of parents refused to have their kids vaccinated with the ‘dangerous’ measles vaccine.

Several successive birth cohorts had significantly lower than optimal vaccination rates. Measles vaccine coverage dropped to 84% by 2002 in the UK, with regional levels (e.g. parts of London) being as low as 61%. By 2006, twenty years after the thoroughly discredited (and now retracted) Lancet paper vaccine rates were still hovering around the mid-80% level.

As immunisation rates dropped below the critical threshold, measles started to circulate again in the population. 56 cases in 1998 to ~450 in the first 6 months of 2006. In that year there was also the first death from measles for many years – an entirely avoidable tragedy.

In 2008 measles was again declared endemic (i.e. circulating in the population) in the UK.

Similar increases in measles, mumps and rubella were occurring across the globe in countries where these diseases were unknown for a generation due to previous widespread vaccination.

The distrust of the MMR vaccine was triggered by the Wakefield paper but is part of a much wider ‘anti-vaccination movement‘.

“Vaccines are dangerous, vaccines themselves cause disease, there are too many vaccines and the immune system is overloaded, vaccines contain preservatives (thiomersal) that are toxic, vaccines cause sterility etc.”

None of these claims stand up to even rudimentary scientific scrutiny.

All have been totally debunked by very extensive scientific analysis.

The World Health Organisation consider the anti-vaccine movement (anti-vaxxers) one of the top ten threats to global health. Vaccination levels are lower than they need to be to protect the population. Diseases – not just measles – that should be almost eradicated now kill children every year.

Where are the bees in this beekeeping blog?

Bear with me … before getting to the bees I want to move from fact (all of the above) to fantasy. The following few paragraphs (fortunately) has not happened (and to emphasise the point it is all italicised). However, it is no more illogical than the claims already being made by the anti-vaccine movement.

Childhood measles

The inexorable rise of internet misinformation and social media strengthened the anti-vaxxers beliefs further. Their claims that vaccines damage the vaccinees were so widespread and, for the uncritical, naturally suspicious or easily influenced who simply wanting to protect their kids, so persuasive that vaccine rates dropped further. They refused to consider the scientific arguments for the benefits of vaccines, and refused to acknowledge the detrimental effects diseases were having on the community.

The obvious causative link to the inevitable increase in disease rates was not missed – by both the anti-vaxxers and those promoting vaccination. However, the solutions each side chose were very different. Measles remained of particular concern as kids were now regularly dying from this once near-forgotten disease. The symptoms were very obvious and outbreaks spread like wildfire in the absence of herd-immunity {{7}}.

The anti-vaxxers were aware that population size was a key determinant of the ability of measles to be maintained in the population. Small populations, such as those on islands or in very isolated regions, had too few new births annually to maintain measles as an endemic disease.

With the increase in remote working – enabled by the same thing (the internet) responsible for lots of the vaccine misinformation – groups of anti-vaxxers started to establish remote closed communities. Contact with the outside world was restricted, as was the size of the community itself.

A quarter of a million was the cutoff … any more than that and there was a chance that measles could get established in the unprotected population.

Small communities {{8}} work very well for some things, but very badly for others. Efficiencies of scale, in education, industry, farming and trade became a problem, leading to increased friction. When disease did occur in these unprotected communities it wreaked havoc. Countless numbers of people suffered devastating disease because of the lack of vaccination.

In due course this led to further fragmentation of the groups. They lived apart, leading isolated lives, flourishing in good years but struggling (or failing completely) when times were hard, or when disease was introduced. Some communities died out altogether.

They chose not to travel because, being unvaccinated, they were susceptible to diseases that were widespread in the environment. Movement and contact between villages, hamlets and then individual farm settlements was restricted further over time.

The benefits of large communities, the division of labour, the economies and efficiencies of scale, were all lost.

They didn’t even enjoy particularly good health.

They had ‘evolved’ into subsistence farmers … again.

OK, that’s enough! Where are the bees?

Anyone who has bothered to read this far and who read Darwinian beekeeping last week will realise that this is meant to be allegorical.

The introduction of Varroa to the honey bee population resulted from the globalisation of beekeeping as an activity, and the consequent juxtaposing of Apis mellifera with Apis cerana colonies.

Without beekeepers it is unlikely that the species jump would have occurred.

Undoubtedly once the jump had occurred transmission of mites between colonies was facilitated by beekeepers keeping colonies close together. We do this for convenience and for the delivery of effective pollination services.

The global spread of mites has been devastating for the honey bee population, for wild bees and for beekeeping.

But (like the introduction to measles in humans) it is an irreversible event.

However, it’s an irreversible event that, by use of effective miticides, can at least be partially mitigated.

Miticides do not do long-term harm to honey bees in the same way that vaccines don’t overload the immune response or introduce toxins or cause autism.

There can be short term side effects – Apiguard stinks and often stops the queen laying. Dribbled oxalic acid damages open brood.

But the colony benefits overall.

Many of the miticides now available are organic acids, acceptable in organic farming and entirely natural (even being part of our regular diet). Some of the hard chemicals used (e.g. the lipid-soluble pyrethroids in Apistan) may accumulate in comb, but I’d argue that there are more effective miticides that should be used instead (e.g. Apivar).

I’m not aware that there is any evidence that miticides ‘weaken’ colonies or individual bees. There’s no suggestion that miticide treatment makes a colony more susceptible to other diseases like the foulbroods or Nosema.

Of course, miticides are not vaccines (though vaccines are being developed) – they are used transiently and provide short to medium term protection from the ravages of the mite and the viruses it transmits.

By the time they are needed again the only bee likely to have been previously exposed is the queen. They benefit the colony and they indirectly benefit the environment. The colony remains strong and healthy, with a populous worker community available for nectar-gathering and pollination.

The much reduced mite load in the colony protects the environment. Mites cannot be spread far and wide when bees drift or through robbing. Other honey bee colonies sharing the environment therefore also benefit.

The genie is out of the bottle and will not go back

Beekeepers (inadvertently) created the Varroa problem and they will not solve it by stopping treatment. Varroa will remain in the environment, in feral colonies and in the stocks of beekeepers who choose to continue treating their colonies.

And in the many colonies of Apis mellifera still kept in the area that overlaps the natural (and currently expanding) range of Apis cerana.

Treatment-free beekeepers may be able to select colonies with partial resistance or tolerance to Varroa, but the mite will remain.

So perhaps the answer is to ban treatment altogether?

What would happen if no colonies anywhere were treated with miticides? What if all beekeepers followed the principles of Darwinian (bee-centric, bee friendly, ‘natural’) beekeeping – well-spaced colonies, allowed to swarm freely, killed off if mite levels become dangerously high – were followed?

Surely you’d end up with resistant stocks?

Yes … possibly … but at what cost?

Commercial beekeeping would stop. Honey would become even scarcer than it already is {{9}}. Pollination contracts would be abandoned. The entire $5bn/yr Californian almond crop would fail, as would numerous other commercial agricultural crops that rely upon pollination by honey bees. There would be major shortages in the food supply chain. Less fruits, more cereals.

Pollination and honey production require strong, healthy populous colonies … and the published evidence indicates that naturally mite resistant/tolerant colonies are small, swarmy and only exist at low density in the environment.

Like the anti-vaxxers opting to live as isolated subsistence farmers again, we would lose an awful lot for the highly questionable ‘benefits’ brought by abandoning treatment.

And like the claims made by the anti-vaxxers, in my view the detrimental consequences of treating colonies with miticides are nebulous and unlikely to stand up to scientific scrutiny.

Does anyone seriously suggest we should abandon vaccination and select a resistant strain of humans that are better able to tolerate measles?

Notes

It is an inauspicious day … Friday the 13th (unlucky for some) with a global pandemic of a new zoonotic viral disease threatening millions. As I write this the UK government is gradually imposing restrictions on movement and meetings. Governments across Europe have already established draconian regional or even national movement bans. Other countries, most notably the USA and Africa, have tested so few people that the extent of Covid-19 is completely unknown, though the statistics of cases/deaths looks extremely serious.

What’s written above is allegorical … and crudely so in places. It seemed an appropriate piece for the current situation. The development of our globalised society has exposed us – and our livestock – to a range of new diseases. We cannot ‘turn the clock back’ without dissasembling what created these new opportunities for pathogens in the first place. And there are knock-on consequences if we did that many do not properly consider.

Keep washing your hands, self-isolate when (not if) necessary, practise social distancing (no handshakes) and remember that your bees are not at risk. There are no coronaviruses of honey bees.

{{1}}: Some artistic licence here as these were domesticated separately in other regions as well over about 4,000 years.

{{2}}: Though hunting – and even the current bushmeat trade – is a known route of transmission though usually ‘dead end’ and not spreading further in humans.

{{3}}: For the technically-minded it has an R0 of 12+. Compare that to Covid-19 which has an R0 of 2 or 3. R0 is the average number of new people infected by an infected individual.

{{4}}: I like the etymological ‘nod’ here to the collective term for cattle as it’s originally a cattle disease that’s being prevented.

{{5}}: No time to cover this, but rinderpest was the second viral disease (after smallpox) to be eradicated by global vaccination. A phenomenal achievement.

{{6}}: I think this is still a beekeeping blog and so this isn’t the place to go into the details here. It’s well-documented in a number of places – for example, look up stuff by Brian Deer. Wakefield was struck off by the GMC in 2010 for serious professional misconduct. The respected British Medical Journal subsequently referred to the 1986 Wakefield study as fraudulent … but the damage had already been done.

{{7}}: Of course, those supporting vaccination simply wanted the safe and effective MMR vaccine widely used again.

{{8}}: And 250,000 is small. In 1991 (the latest data I could find) this would exclude all towns larger than Hull (UK) or Gilbert, Arizona (USA).

{{9}}: With even more profit to be made from adulterated imported syrup sold as honey.

Join the discussion ...