Coordinated Varroa control

In the magnum opus last week I discussed how bees discriminate nestmates from non-nestmates at the hive entrance. Inevitably I had to discuss the processes of drifting and robbing as these activities, together with the peripatetic drones, largely account for the ‘foreign’ bees arriving at a hive entrance.

I described drifting as a short-range phenomenon, predominantly of bees with immature cuticular hydrocarbon profiles {{1}}, on their first few orientation flights. In contrast, I described robbing as a potentially long-range event that could occur over at least one kilometre.

I should have re-read the literature and refreshed my memory of what others have already reported for these activities before writing the post 🙁 .

Peck and Seeley (2019) demonstrated the importance of robbing in mite transmission, and – of necessity – discriminated between bees that were robbing and those that were drifting. In their study they demonstrated drifting occurred over distances of at least 300 metres, much greater than I remembered.

Not such short-range after all.

In addition, I re-discovered Eva Frey’s paper (Frey et al., 2011) on robbing, showing it occurs over at least 1.5 km.

Both robbing and drifting of workers, and possibly drifting of drones, mediate the transmission of Varroa and deformed wing virus (DWV) between colonies in the environment.

All of which means that when you’re considering Varroa control you should not restrict your thinking to your hive, or the hives in your apiary, but should instead consider a much larger area encompassing other colonies “within range”.

Colonies in the environment

I’ve discussed this general topic before, so I’ll try and whizz through it quickly.

The hive vs the apiary

Your hive sits in your apiary.

It may be the only hive in the apiary or it may share the space. The other hives in the apiary may be yours, or – in the case of an association apiary – may belong to others.

The association apiary …

You should consider all the hives in the apiary as a single location. The bees will move between them reasonably freely and the Varroa and virus will be shared out … not necessarily equally, but they will certainly be well distributed between all the hives in the apiary.

I’ve previously moved mite-free colonies into infested apiaries. Mites are detectable in the introduced colony within days, and DWV symptomatic bees within a month or two.

When it comes to applying the late summer miticide treatment to colonies it makes zero sense to treat hives within the same apiary at different times. Equally, it makes no sense to treat some and not treat others.

Are you sure some really have a lower Varroa infestation level (the only possible justification I can think of to not treat them)? Have you conducted phoretic mite counts i.e. sugar roll, or alcohol washes?

Even if you’ve done these, are you sure there are similar capped brood levels and the queens have been laying at equivalent rates? These, at least theoretically, influence phoretic mite levels.

Different hives and different beekeepers taking honey supers off at different times? {{2}}

Find a different apiary and move your bees there 😉 .

That may sound flippant, but I’m completely serious

Imagine the scenario. You have a couple of hives in the association apiary. There are the association hives and a handful belonging to another couple of beekeepers – let’s call them Laurel and Hardy.

You, the association apiary manager and Laurel take your honey supers off in mid-August. You live somewhere relatively warm and so use Apiguard to treat the colonies. Apiguard is applied for one month. Much later than mid/late September and it would be too cold for effective treatment anyway.

Hardy however has different ideas. He’s away most of August. By the time he returns he reckons he can get ‘a bit more honey’ from the rosebay willow herb. Before you know it his supers are still on and it’s late-September. By then the ivy is yielding and Hardy’s getting greedy … he delays treatment a bit longer.

Mites have been replicating in Hardy’s colonies for at least a month more after you applied miticide to most of the hives in the apiary. Mite levels will now be significantly higher. If the weather stays warm and the bees continue to rear brood – and go on orientation flights – the mites from Hardy’s colonies will end up in all the recently miticide-treated colonies in the apiary.

Thanks … for nothing!

Willow herb (fireweed), mid-August 2015

But it could be worse.

Hardy {{3}} failed to treat his colonies last year at all and they are absolutely hooching with mites.

Riddled, they are. Boggin.

And, shortly after he returned from his August holiday and hoped to squeeze another super of honey from the RBWH, his colonies started collapsing with varroosis.

And so your miticide-treated colonies start robbing out his expiring mite-infested hives.

You may as well have not treated … 🙁 .

The apiary vs the environment

So, you sensibly move your colonies from the shared apiary into one you have total control over.

You can treat when you want. You no longer need to consider Hardy and his attempts to become a world-champion mite keeper.

Your troubles are over … or are they?

Hardy’s mentor – who taught Hardy all he doesn’t know about mite control – keeps bees on the other side of that distant copse at the end of the field.

They’re no more than 300 metres from your apiary … but you didn’t even know they were there. Hardy’s mentor visits them so infrequently you’ve never seen him.

If you think this is an unlikely scenario, think again. Do you know of every hive-shaped nook or cranny within 300 metres of your apiary? What about 1.5 km?

What about all those urban beekeepers who may not even know their neighbours, let alone the contents of their high-fenced back gardens?

How many urban back gardens are there within 1.5 km? … hundreds, thousands?

Or urban rooftop bees …

Your bees almost certainly share the environment they occupy with lots of bees from other hives. Yes, there are certainly exceptions, but the vast majority of honey bees in the UK will be in this type of environment.

And that’s before we consider the feral colonies … which we won’t.

Hive density in the environment

If your apiary is registered on the National Bee Unit’s Beebase system (and it jolly well should be) you can get a pretty good idea of the local hive density.

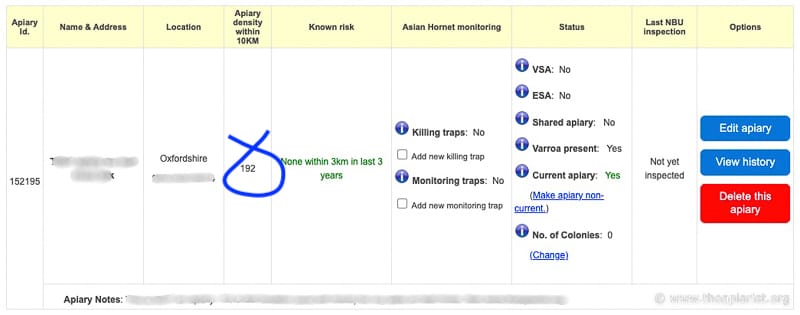

Beebase shows the ‘density’ of apiaries within 10 km

The figure in the column ‘apiary density within 10 km’ can be used to calculate the approximate number of hives in the ‘local’ environment.

You have to make some assumptions here … there are ~ 50,000 beekeepers running ~250,000 colonies in the UK. Some are commercials, many of which move their bees around the country (so could ‘occupy’ several apiaries in a single year).

Some apiaries will have just one or two hives, others might have 20 or more.

My guesstimate is that the average UK apiary contains 5 hives.

Go on … show me I’m wrong 😉 .

I’d love to have some accurate data here but it’s all wrapped up with the NBU and Data Protection Act.

I’ve quoted 5 before and no-one has suggested I’m a long way out.

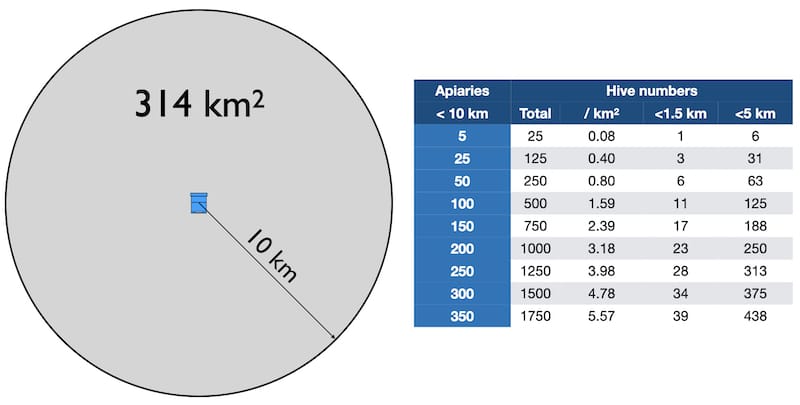

A 10 km radius produces a circle with an area of 314 km2 . The Beebase figure tells us the number of apiaries within that area. You can therefore calculate the number of hives per square kilometre within that circle, and from that, the number of hives within 1.5 km or 5 km.

But I’ve saved you the effort … {{4}}

Hive density – see text for details

Why 1.5 and 5 km? The first is the distance over which Frey et al., (2011) showed robbing occurs, and the second (5 km = ~3 miles) is often quoted as the maximum foraging range of a worker {{5}}.

So, if Beebase informs you there are 100 apiaries within 10 km you could reasonably expect there might be 11 hives within robbing distance of your hive, or 125 hives within worker flying range.

How accurate are these figures?

I don’t know.

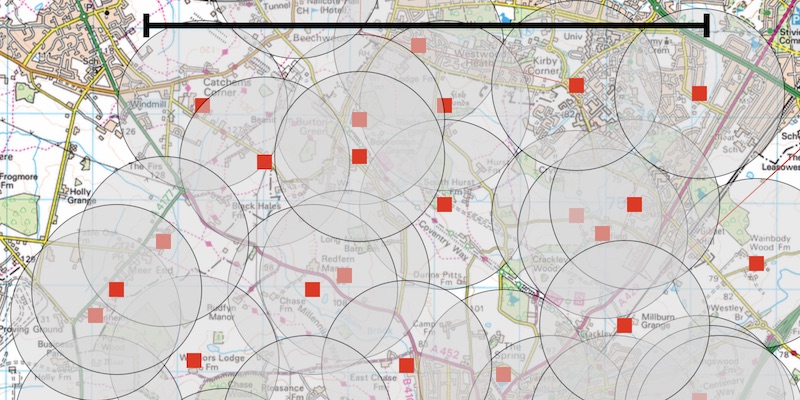

When I lived in Warwickshire there were about 250-275 apiaries within 10 km of mine. Almost every field seemed to have bees on it. My short evening walks would take me past a couple of dozen hives belonging to other beekeepers.

A very careful look at Google maps satellite images turned up two apiaries within ~3 km I never knew existed (and I’d been living there for several years).

When I talk to associations about bait hives I ask them the postcode of their association apiary and look it up on Beebase. Many have 150 or more apiaries within 10 km. Some have almost 300. It’s very high in some cities.

My Fife apiaries have 50-60 within 10 km. One is on the edge of a town and I’ve no idea where other bees are. I know of at least a dozen other hives within 1.5 km of my rural apiary.

Apiary density (those I knew of … there were more) in Warwickshire. Scale bar = 10 km. Circles are 1.5 km radius.

Check your apiaries on Beebase.

Check my maths 😉 .

You might be surprised.

This is the environment in which you are trying to control Varroa infestation.

And all of the above assumes that hives are static. They’re not. Beekeepers are forever moving them about … between apiaries, selling them, moving them to the OSR or whatever. All of this just makes the problem worse.

Of course, hives are not evenly distributed in these neat circles of radius 1.5, 5 or 10 km, but let’s not make it more complicated than it already is 😉 .

Read the instructions

In Infernal contradictions I discussed the poor quality instructions that accompany some miticides sold in the UK. Only some because I ran out of space. I have yet to write about other miticides which are also supplied with equally shonky instructions.

Bad, but in different ways 🙁 .

However, one thing that most {{6}} miticide instructions state is something like:

Treat all colonies in the apiary at the same time (MAQS)

Treat all colonies in an apiary simultaneously (Apivar)

All colonies in the same apiary should be treated simultaneously to avoid reinfestations (Api-Bioxal)

Kudos to Api-Bioxal for explaining why; instructions make more sense when there is some explanation included.

The miticide manufacturers generally appreciate the importance of coordinately treating colonies in the same apiary. That’s a good start.

But – based upon the scenario with Hardy’s mentor outlined above – why is there never any mention of collaborating with neighbouring beekeepers to coordinately treat all the colonies sharing the environment?

That’s a rhetorical question.

I can think of several likely answers; some of these reflect badly on the manufacturer, some reflect poorly on the beekeeper, and most of which are because it’s not necessarily a very easy thing to achieve.

Which doesn’t mean you shouldn’t try.

Landscape-scale coordinated Varroa control

There is compelling science that shows the ‘environment’ used by your colonies extends well beyond the confines of the apiary, and that it is probably shared by many other colonies {{7}}.

However, there are numerous examples of successful coordinated pathogen and/or parasite control at the landscape-scale; sea-lice in salmon farms, cattle tick fever, visceral leishmaniasis, mosquito/malaria/Zika virus etc.

I’m aware of at least two previous attempts at coordinated Varroa control. They were either small-scale and/or inconclusive. This isn’t a criticism … these are not easy experiments to do.

As we discovered 😉 .

Full disclosure: I’m the senior {{8}} author of the study I introduce below on coordinated Varroa control at the landscape scale.

The density of managed colonies in the UK makes any sort of comprehensive landscape-scale control initiative very difficult to study. Not all colonies are documented, not all beekeepers are known, not all want to take part etc.

What we needed was an isolated area with a reasonable number of colonies that could be managed coordinately. The obvious choice was an island, separated from other bees by an expanse of water over which bees were unlikely to fly.

After discussions with our collaborators in SASA {{9}} and SRUC {{10}} we approached the Arran Bee Group (ABG) on the Isle of Arran. All the known beekeepers on the island belong to the ABG.

Arran, the ABG and the study design

Arran is a 430 km2 island in the Firth of Clyde. There are ~4700 residents of which ~50 are beekeepers who were managing 57 colonies at the outset of the study. Arran is a popular tourist destination with, amongst other attractions, excellent hillwalking in the central upland areas. Most residents live around the coast, in small towns or villages such as Brodick, Lamlash or Lochranza.

Cir Mhor and Caisteal Abhail from Goatfell, Arran

The ABG very generously agreed to take part in the study. Essentially this involved coordinated late summer miticide treatments using Apivar, followed in the winter by an application of trickled Api-Bioxal. The latter was not coordinated as there is no drifting or robbing (or flying for that matter) happening in December.

Each summer for three years Luke Woodford, my then PhD student (and now a post-doctoral fellow in the University of Stirling), would visit the island to apply the coordinated treatment, more than ably helped by Graeme Sharp from SRUC.

I would sometimes tag along to get in the way, chat with beekeepers and cause problems.

At the same time the summer miticides were applied Luke would take a sample of nurse bees to test for viruses. The ABG would collect all the mites that dropped during treatment and post them back for analysis in St Andrews.

Lamlash dawn looking to Holy Island

An important component of the study was that the importation of bees was stopped during the study. This would have otherwise been a source of new viruses and Varroa which would have confounded the (already extensive) data analysis. The ABG also documented the movement of hives and nucs between apiaries on the island.

It’s worth emphasising here that this study would not have been possible without the enthusiastic support of the ABG for which all the authors are extremely grateful.

Results in brief

The paper is freely available (Woodford et al., 2023) … it’s not necessarily ’easy listening reading’ but the bits that I didn’t write are relatively straightforward to read {{11}}. The study started in mid-2017 and ended in late summer 2019.

The Isle of Arran

The key results were as follows:

- 29/57 colonies were lost in the first winter due to a combination of adverse weather and high mite and virus levels. We presume that our initial treatment was applied too late to save colonies with pre-existing high mite levels.

- By the end of 2018 ABG managed 54 colonies, and this number increased to 84 colonies by the end of the study period in 2019.

- Average mite drop/colony in the 7 days following summer Apivar treatment was 683 (2017), 226 (2018) and 303 (2019). Overall there was a reduction in mite levels across the island of ~60%.

- Average DWV levels dropped from 8 x 105 in 2017 to 4 x 104 in 2019 {{12}}. This is a 20-fold reduction in virus levels.

- We observed a shift (partial or complete) of a type A strain of DWV to a type B strain across the entire island, possibly due to the origin of nucs and/or the replication characteristics of the virus.

- There was considerable apiary-to-apiary variation in terms of mite/virus level reductions, probably due to different management methods, forage, colony genetics or one of a thousand other potential variables.

- There were no controls.

What? No controls? No funding?

Generally scientific experiments are ‘controlled’ by conducting a parallel set of studies in which only one thing is varied.

For example, the coordination or not of the miticide treatment.

By doing this you can determine whether the thing you are testing has a significant impact on whatever you are investigating.

But that’s a problem in this type of study. It would mean we would need to find another 430 km2 island off the west coast of Scotland, sharing the same climate, forage, number (and experience) of beekeepers, colony numbers, management methods etc.

Nope … not going to happen.

There are other ways to control for variables such as weather but these almost always involve multiple repeats over many years.

All of these things make the study less definitive than it could have been. Money and time were also finite.

As an aside, we had approached one of the beekeeping charities to fund a small part of the study. They politely refused stating that ’whilst the science is excellent you will not get the beekeepers to work together and collaborate with you’.

Thanks … for nothing!

Frankly, that was the easy part. ABG could not have been more welcoming and accommodating.

Take home messages

Despite the absence of controls I think there are some very positive outcomes from this study.

Mite and virus levels decreased significantly during the study period over the island. Equally importantly, and I would argue as a consequence of the resulting improvement in colony health, the ABG readily made up colony losses experienced in the 2017 winter, and ended up with significantly more colonies than they had started with.

It should be noted that we only provided advice or practical instruction in Varroa management and that the ABG had previously suffered unsustainable colony losses attributed to mites and the viruses they transmit. However, with healthier colonies they were better able to ‘make increase’.

Isolated apiaries on the island tended to have lower mite levels by 2019 and showed the greatest decrease in mite and virus levels.

In contrast, one site (containing three neighbouring apiaries) had resolutely high virus and mite levels throughout the study. Colonies moved from here to remote apiaries {{13}} were associated with exacerbation of mite and virus levels at the landscape level.

It seemed likely to us that the management of these colonies, or the local environment, was conducive to either better mite reproduction (e.g. more drone brood in the colonies) or less effective miticide treatment outcomes.

The island-wide replacement of one type of DWV with another was interesting, and has also been seen in other survey-type studies. There are suggestions that type B DWV persists in miticide-treated colonies, whereas the type A variant is dependent upon mites for sustained transmission and is lost (or at least significantly reduced) when mite levels are lowered. We have previously demonstrated that type B DWV replicates in mites, in contrast to type A DWV (Gusachenko et al., 2020).

More work

Clearly more work is needed, but I think this is a promising start {{14}}.

However, even without good – well controlled – scientific evidence showing dramatic improvements in colony health attributed to reductions in mite and virus levels, our understanding of the biology of honey bees strongly suggests that coordinated miticide applications during late summer will be beneficial.

How that is best achieved on a scale larger than that of individual apiaries remains to be determined. At the very least, associations should promote it amongst their members, and government bodies involved in bee health should encourage it.

Varroa control is simple in principle, but difficult in practice.

The timing of both the summer and winter treatments is critical. The former must be early enough to protect what should be the long-lived winter bees. The winter treatment must be during a broodless period for maximal efficacy.

This timing may differ from year to year, and definitely does differ across the country.

And if that wasn’t difficult enough to grasp I’m now advocating coordinating one of these critical events – the late summer treatment – with all your neighbouring beekeepers.

Go for it!

References

Frey, E., Schnell, H., and Rosenkranz, P. (2011) Invasion of Varroa destructor mites into mite-free honey bee colonies under the controlled conditions of a military training area. Journal of Apicultural Research 50: 138–144 https://doi.org/10.3896/IBRA.1.50.2.05.

Gusachenko, O.N., Woodford, L., Balbirnie-Cumming, K., Campbell, E.M., Christie, C.R., Bowman, A.S., and Evans, D.J. (2020) Green Bees: Reverse Genetic Analysis of Deformed Wing Virus Transmission, Replication, and Tropism. Viruses 12: 532 https://www.mdpi.com/1999-4915/12/5/532.

Peck, D.T., and Seeley, T.D. (2019) Mite bombs or robber lures? The roles of drifting and robbing in Varroa destructor transmission from collapsing honey bee colonies to their neighbors. PLOS ONE 14: e0218392 https://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0218392.

Woodford, L., Sharpe, G., Highet, F., and Evans, D.J. All together now: Geographically coordinated miticide treatment benefits honey bee health. Journal of Applied Ecology n/a https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/1365-2664.14367.

{{1}}: My speculation, but I’m repeating it here to claim priority over the idea ;-)

{{2}}: i.e. some cannot be treated as the miticide is incompatible with the presence of honey supers, as almost all of them are.

{{3}}: Who you’re beginning to realise is a bit of a clown.

{{4}}: You can thank me later.

{{5}}: Except it isn’t the maximum range, but it’s rare they travel further.

{{6}}: Not all … Oxuvar appears not to mention this. Tut tut.

{{7}}: And possibly some feral colonies.

{{8}}: Age, if nothing else.

{{9}}: Science and Advice for Scottish Agriculture

{{10}}: Scotland’s Rural College

{{11}}: And better punctuated than these posts.

{{12}}: Units are a confusing Genome Equivalents per microgram of total RNA per worker (I bet you’re sorry you asked).

{{13}}: We did not restrict how the ABG managed their bees.

{{14}}: But then I would, wouldn’t I!

Join the discussion ...