Mites equal viruses

Healthy bees are happy bees ?

Sounds good doesn’t it?

Actually, there’s no evidence that bees display or perceive most of the emotions often attributed to them {{1}}.

A more accurate statement might be “Healthy bees are more productive, they are less likely to die overwinter, less likely to be robbed out by wasps or neighbouring strong colonies and their parasites and pathogens cannot threaten the health of other honey bee colonies or, through so-called-pathogen overspill, the health of other pollinators.”

More accurate?

Yes … but it doesn’t exactly trip off the tongue ?

Whether it makes the bees happy or not, beekeepers have a responsibility to look after the health of their livestock. This includes controlling Varroa numbers to reduce the levels of pathogenic viruses in the hive.

How well are virus levels controlled if mite levels are reduced?

I’ll get to that in due course …

Midwinter mite massacre

The 2018 autumn was relatively mild through until mid/late November. In the absence of very early frosts colonies continued rearing brood.

We opened colonies in mid-November (for work) and found sealed brood, though it was clear that the laying rate of the queen was much-reduced.

These are ideal conditions for residual mite replication. Any mites that escaped the late summer/early autumn treatment (the ideal time to treat to protect the overwintering bees) continue to replicate, resulting in the colony starting the following season with a disappointingly high level of mites.

I’ve noted before that midwinter mite levels are paradoxically higher if you treat early enough in the autumn to protect the all-important winter bees.

Consequently, to start the year with minimal mite levels, I treat in midwinter with a trickled or vaporised oxalic acid-containing (OA) treatment.

A combination of colder weather (hard frosts in late November) and brood temperature measurements {{2}} indicated mid-December was a good time to treat.

18th December

In one of my apiaries ten colonies were treated. Some were definitely broodless (based upon Arnia hive monitoring). Others may have had brood, but colonies were not routinely checked.

Over the four day period after vaporising these ten colonies dropped a total of 92 mites. More than 50% of these were from just one double-brooded colony. Overwintering nucs {{3}} dropped no mites at all in the 12 days following treatment.

This was very encouraging. These are lower midwinter mite levels than I’ve seen since returning to Scotland in 2015.

The one colony with ‘high’ mite levels received two further treatments (on the 22nd and 27th) in an attempt to minimise the mite levels for the start of the season. Going by the strength of the colony and the debris on the Varroa tray it was presumed that this colony was still rearing brood.

Mite drop following the third treatment was negligible {{4}}.

Why are mite levels so low?

I think it’s a combination of:

LuckUse of natural, organic, bee-centric and biodynamic beekeeping methodsVarroa-resistant bees- Very tight control of mite numbers in the 2017/18 season, primarily by correctly timing the winter and the late-season autumn treatments. This is simply good colony management. Anyone can achieve this.

- A brood break midseason and/or a broodless period when splitting colonies (both give opportunities for more phoretic mites to be lost through grooming). Undoubtedly beneficial but season-dependent. I’ll be discussing ways to exploit these events in posts next year.

- A low density of beekeepers in Fife, so relatively little drifting or robbing of poorly managed colonies from neighbouring apiaries. Geography-dependent. Much easier in Fife than Warwickshire … and easier still in Lochaber.

And what do less mites mean?

Varroa is a threat to bee health because it transmits pathogenic viruses when feeding on developing pupae.

The most important of these viruses is deformed wing virus (DWV).

Generally, the higher the level of infestation with mites, the higher the viral load {{5}}. This has been repeatedly demonstrated by studies from researchers working in the UK, Europe and the USA.

It is well-established that colonies with high viral loads have an increased chance of dying overwinter, due to the decreased longevity of bees infected with high levels of virus.

In our work apiaries we regularly measure DWV levels. For routine screening our limit of detection is around 1,000 viruses per bee.

We don’t actually count the viruses. They’re too small to see without an electron microscope {{6}}.

Instead, we quantify the amount of the virus genetic material present {{7}}, compare it to a set of standards and express it as ‘genome equivalents (GE)’.

Many of the bees tested this year contained ~103 (i.e. 1000) GE, which is extremely low. Bees from Varroa-free regions (e.g. Colonsay) carry similar levels of DWV.

Most of our colonies were at or close to this level of virus much of the 2018 season. This is 100-1,000 times lower than we often see even in apparently perfectly healthy colonies in other years or other apiaries.

For comparison, using the same assay we usually detect about 1010 (ten billion) DWV GE per bee in symptomatic adult bees from heavily mite-infested colonies.

So, less mites means less viruses which means healthier bees ?

And they might even be happier bees ?

And your point is?

It’s worth remembering that the purpose of treating a colony with miticides is to reduce the transmission of viruses between bees. This transmission results in the amplification of DWV. This is why the timing of treatments is so important.

Yes, it’s always good to slaughter a few (or a few thousand ? ) mites. However, far better massacre them when you need to protect particular populations of bees.

This includes the overwintering bees, raised in September, that get the colony through to the Spring.

Remember also that it ‘takes bees to make bees’ i.e. the rearing of new brood requires bees. Therefore strong colony build-up in Spring requires healthy workers rearing healthy brood.

This is why it’s important to minimise mite levels in midwinter when colonies are broodless.

What do most beekeepers do?

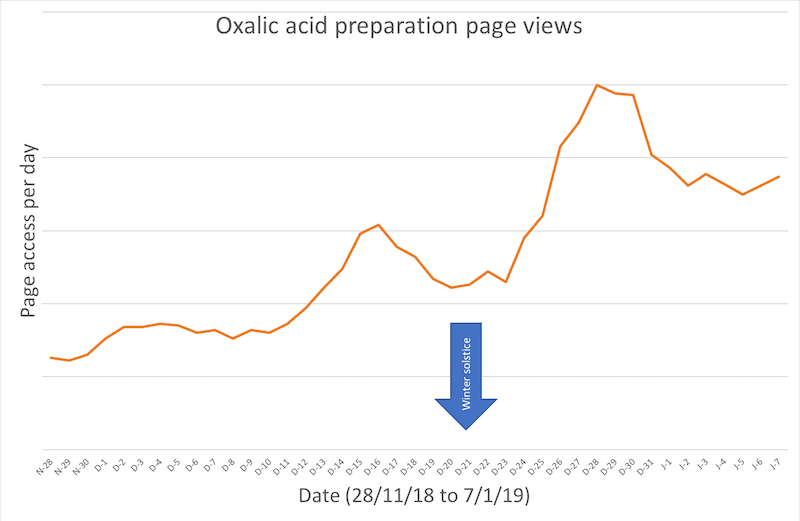

Fifteen months ago I published a post on the preparation of oxalic acid solutions for trickling colonies in midwinter.

Whatever the vapoholics on the online forums claim, trickling remains the easiest, quickest and least expensive way to treat colonies in midwinter {{8}}.

The best time to treat in the winter is when the colony is broodless. Here in Fife, and often elsewhere, I believe that this usually occurs earlier in the winter than many beekeepers treat (if it happens at all … or if they treat at all).

I usually treat between the end of the third week in November and mid-December, at the end of the first extended cold period.

Looking at the page views for these oxalic acid recipes it looks as though many beekeepers treat after Christmas {{9}} … which may be suboptimal if colonies had a broodless period and now started rearing brood again.

Mine have.

This winter has been quite mild (at least at the time of writing) so there may yet be opportunities to treat really effectively during a broodless period.

Or the chance may have gone …

{{1}}: Though both bumble bees and honey bees may show some fundamental emotional responses such as optimism and have basic stress responses

{{2}}: Determined using Arnia hive monitors – see the final graph on a recent post.

{{3}}: All my winter nucs are in the Thorne’s polystyrene Everynuc and are looking reassuringly strong and healthy.

{{4}}: Just three in a fortnight.

{{5}}: There are exceptions to this – for example, a colony that has very recently been treated to reduce a heavy mite infestation. In this situation – assuming the treatment was successful – the viral load will be very high, but the mite levels will be very low. What happens to this viral load? Does it remain high or does it decrease?

{{6}}: And even with an electron microscope they’re a real pain to count. So we don’t.

{{7}}: For the nerdier readers this uses a technique termed qRT-PCR; quantitative reverse-transcription polymerase chain reaction.

{{8}}: And I’m happy to acknowledge this despite usually using sublimation to treat my own colonies. I prefer to sublimate (‘vape’) as it is better tolerated by colonies and does not harm open brood (should there be any).

{{9}}: Assuming, of course, that they’re accessing the recipe on or before the date they treat!

Join the discussion ...