Neither revolution nor resolution

My bees were flying on Christmas Day.

It seemed a little incongruous. The Christmas tree was festooned with cards featuring robins in the snow, or Santa's sleigh, or carrot-nosed snowmen, but it was a balmy 11°C at midday, and the bees were taking full advantage of it.

These flights are generally short 'cleansing flights', a euphemism used in the polite beekeeping circles for a variety of alternatives, including some better suited to the children's nursery, the locker room, or the laboratory {{1}}.

Taking advantage of the facilities - or in this case, the benign weather - is a wise decision. If the weather turns cold for a protracted period it might be another couple of months before they can get out again.

But, it's not just cleansing flights that happen during warmer periods of the winter. Some bees will be out collecting water and some may even be foraging if there's something suitable nearby. Gorse (Ulex europaeus) is a likely candidate as can be found flowering throughout the year. In my part of the world there's usually gorse within sight of my hives.

Bees need water throughout the year. In weather too cold to fly I've always assumed they get it from condensation on the inner-walls of the hive, but as soon as it's warm enough to venture out, they do.

Today, although the air temperature hovered around freezing, bees walked out of the entrance of the hives in full sun to collect melted ice from the landing board of my overwintering nucs.

Bring out your dead

Of course, the other thing the bees do during these periods of better weather is some hive 'housekeeping'.

During long periods of confinement there is an inevitable build-up of corpses on the floor of the hive. Once the weather warms sufficiently - even temporarily - the undertaker bees remove these, typically dropping them not far from the hive entrance {{2}}.

I discussed how these undertakers probably identify corpses for 'necrophoresis' last October; in contrast to the removal of dead pupae {{3}}, it is probably the absence of the volatile chemicals heptacosane and nonacosane from cold, dead corpses that triggers their removal.

However, a new or inexperienced beekeeper is not likely to know or care about the chemicals involved ... they're just concerned about the pile of corpses in front of the hive.

Is the colony dying? Will they survive?

From late summer to early winter there is a near-complete turnover of the worker population in the hive, with the diutinus (long-lived) winter bees replacing the short-lived summer bees. During this period the hive population also gets smaller. Although the winter bees live longer, some do still die overwinter. At least during the first part of winter, there are also some summer bee 'stragglers' dying off as well (see the colourful graph and accompanying text in my previous discussion of undertaker bees and hygienic behaviour).

All of which means that corpses - hundreds of them - will fall to the hive floor during protracted periods of cold weather, and will be unceremoniously 'turfed out' once the weather warms sufficiently.

Don't worry about it.

If the hive is heavy (i.e. it has sufficient stores) and the bees are as mite-free as realistically achievable (thanks to timely and appropriate miticide treatment) then they should be OK.

Whatever you do, don't crawl around looking for bees with deformed wings {{4}}. The corpses will be old, tatty and weather-beaten; even Dr. Alexx Woods couldn't make a definitive diagnosis.

That's ~700 words in which I've managed to avoid the subject referred to in the title of this post, so I'd better get back on track.

Resolutions

People have been making New Year's resolutions for at least 4,000 years. The Babylonians made them retrospectively, returning a kindness, righting a wrong or repaying a debt.

The Mesopotamian New Year (Akitu) was based upon the lunar calendar and was usually in March or April, but the principle remains broadly the same.

Resolutions are good deeds, or 'improvements', which we now make prospectively.

Though we usually do not to keep them, 😔.

Scientific studies suggest that, a year later, only ~12% of resolutions are actually kept. Even if asked on the day they were set, only ~50% expected to keep them. That's a little defeatist if you ask me ... with expectations that low, is it any wonder most are missed?

So, although I've previously suggested some rather contrived beekeeping resolutions {{5}} I'm not going to bother doing anything so specific this year.

Oh well, if you insist ...

Most resolutions fall into one of four categories; goal-, happiness-, pride- or purpose-based. Of these, the first are by far the most common set ... and the least likely to be achieved.

- 'I will make my beekeeping very profitable by selling lots of queens and nucs' ... clearly goal-based, and at risk of failing due to vagaries in the weather, personal illness, an EFB outbreak nearby or any number of other things.

- 'I will spend 30 minutes in the apiary before opening a hive just enjoying watching and listening to the bees' ... happiness-based, relaxing and pleasurable. You'll be amazed at the things you see; queens returning from mating flights, helicopter-like hornets {{6}} hawking at the hive entrance, or a barn owl quartering the meadows searching for prey. I've seen all these over the years, and lots more, and it has improved both my beekeeping and enjoyment of the environment.

- 'I will attend a training course and learn a new skill (e.g. microscopy, skep or candle making) for my beekeeping' ... pride-based, relatively easy to keep and with defined benefits for the future. What's not to like?

- 'I will try to be less blinkered or biased when discussing treatment-free beekeeping/miticide usage/Buckfast queens/native black bees/free-living colonies/mite bombs/poly hives/cedar hives/open mesh floors/hive insulation/smokers (delete as appropriate)' ... purpose-based, a bit more difficult to achieve, but likely to improve your beekeeping rather than unquestioningly doing what you've always done. I restricted myself to a limited number of topics that beekeepers can argue about ... if you want more, visit the online discussion forums to see the wide range of topics that beekeepers disagree on, often with little or no appreciation of both sides of the argument.

Whatever resolutions you set - if any - keeping them may not be easy.

Your chances of achieving them are improved if they are specific, if you persist (keep going, even if there are setbacks), if others know about them and if you keep records {{7}}.

I don't make resolutions, but I have achieved or am attempting to achieve three of the four things above (those that are happiness-, pride- and purpose-based). In particular, over recent years I've tried to read around some of the topics that beekeepers often feel strongly about - free-living bees, pollinator competition, use of chemicals (both for beekeeping and environmental), insulation/hive materials, treatment free management etc. - and realise that these are often a lot more nuanced than I originally thought.

It's been an education, and an enjoyable one.

'Profitable' beekeeping? Oh, how we laughed 😉.

Revolution not evolution

Beekeeping is a very conservative pastime. We keep our bees using broadly similar equipment and methods to those used by Brother Adam 75 years ago, or by L.L. Langstroth a century before that.

Partly, this is a case of "if it ain't broke, don't fix it". Langstroth's removable frame hive, the exploitation of bee space, and the use of an excluder to restrict the queen to the bottom box(es), all are fundamentally unchanged since the 1850s.

Of course, there have been some minor changes in the design of the hive (and dozens of 'new' hive types ... all pretty-much indistinguishable without a ruler), or in the material from which it is made, but these are all variations on a theme.

Variations, but not necessarily improvements.

And the same comments apply to the methods we use to keep bees. Langstroth's book, The hive and the honey-bee, was published in 1853, is still in print today {{8}} and the methods described remain easily recognisable (even though the writing, understandably, looks a little dated).

What's the biggest revolution that's occurred in beekeeping in the last 175 years?

It's not poly nucs, or the Flow Hive, or grafting larvae for queen rearing {{9}}.

I'd argue that it's the introduction and global spread of Varroa in the honey bee population. With a few exceptions - many tropical or subtropical regions, or those naturally Varroa-free - the presence of mites significantly impacts the majority of beekeepers.

Everything else is the gradual evolution of our pastime ... some new materials, subtle changes to the methods we use etc.

Evolution not revolution

I rather like this conservatism in beekeeping. It's reassuring to think that the methods and equipment I'm using are broadly similar to those that have been used - successfully, and by much better beekeepers than me - for almost two centuries.

Compare that to so many other hobbies and pastimes, where there is often never-ending pressure to get the latest and best equipment.

Those teetering stacks of boxes I've acquired over the last decade or more will outlast me, and should remain usable for decades more ... but the camera used to take the photos for this post is unlikely to survive this decade (in fact, the camera used to take a couple of the photos above has already stopped working {{10}}).

So, why do things change so slowly in beekeeping? And, related, why is there not more general agreement that X is better than Y, where X and Y could be hive designs, hive materials or beekeeping methods?

I think the first question is relatively easy to answer. Beekeeping methods are inextricably linked to the life cycle of the honey bee and the environment in which the bees live. The life cycle is effectively invariant. The development cycle of the queen is the same 16 days now as it was for Brother Adam, Langstroth or Doolittle ... or for that matter Nicoli Jacobis in 1568 (though you'll need to read one of the footnotes to understand who Jacobis was).

Similarly, the development of the colony - expansion, swarming, honey collection etc. - is related to the life cycle of the individual honey bees in the colony, and the availability of nectar and pollen in the environment. And the latter is determined by the never-ending cycle of the seasons; day length, temperature, rainfall etc.

'Never-ending', but not invariant.

December

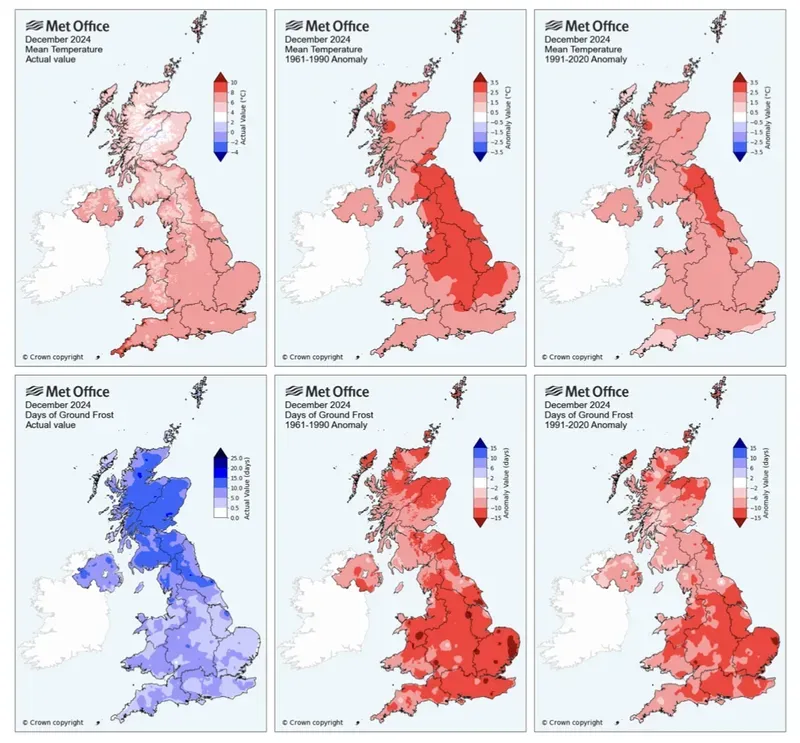

I'll briefly return to the start of the post where I described my bees flying on Christmas Day. I checked the Met Office anomaly maps for December - in particular the temperature and the days of ground frost.

December was unseasonably warm. The composite image above shows the mean temperature (top row) and the days of ground frost. The left column shows actual values, the centre column the anomaly from the period 1961-1990, and the right column the anomaly from the period 1991-2020.

In my part of the world (Scottish Borders), the mean temperature was 4-6°C, a +1.5-2°C increase over the last 30-year average, and +2.5-3.5°C warmer than the period 1961-1990.

These differences are reflected in the days of ground frost ... we had 10-15 days in December 2024, 6-10 less than experienced between 1991 and 2020, and about half that averaged between 1961 and 1990.

This is just one month, but this will have an impact on the bees ... how long they rear brood for, the energy they use to thermoregulate the cluster and the rate at which they use up their stores.

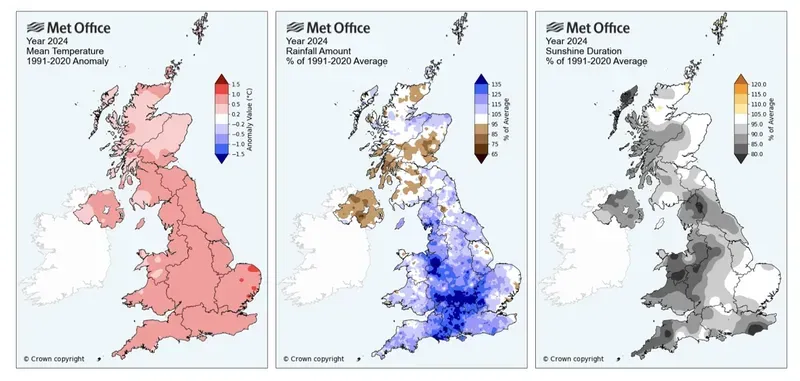

But it wasn't just December ... 2024 was the fourth-warmest year on record. When compared to the last 30 years, it was warmer, wetter and duller.

With this sort of variation, is it any wonder that beekeeping is relatively conservative? We need equipment and methods that can adapt, whatever the conditions.

Variable and changing

And that second question?

'Why is there not more general agreement that X is better than Y, where X and Y could be hive designs, hive materials or beekeeping methods?'

Our bees live in an ever-changing environment. Some years are warmer than others, some wetter, some windier. This influences the flowering of plants and trees; the timing of flowering onset, the duration of flowering, the amount of nectar produced, the sugar concentration of the nectar, and the amount and protein content of pollen.

These differ from year to year, and from place to place.

And the bees differ ... even in the same location, some colonies do better or worse than others.

For example, when scientists 'equalise' colonies for a comparative study - by using sister queens heading identically-managed colonies in the same apiary that start with equivalent amounts of brood and stores - it is not unusual to observe very large variations in colony performance over the subsequent months.

Why? I don't know, but I bet it's got something to do with the genetics of the hive and the differing age populations of the brood and workers ... older bees = more foraging initially, lots of uncapped brood = a delay in forager generation {{11}}.

This being the case, what chance is there that beekeepers will ever agree that poly hives from supplier A are consistently better than cedar hives from supplier B?

Or any other X vs. Y comparison.

These beekeepers live in different locations, at different latitudes, with different strains of bees, subjected to different weather, with different forage, and use different management techniques based upon their different amount of experience (and I've not even mentioned the - often significant - differences in their skill as beekeepers).

And ... if that wasn't bad enough ... they're generally making comparisons based upon only a few colonies.

These make the results statistically meaningless.

It's probably true to say that there is no best beekeeping method, or strategy, or equipment.

Most things work; a little better or a little worse perhaps, but usually well enough.

What matters is that they work for you.

And that's a very important thing to remember when you're starting beekeeping, or trying a different method of achieving something.

Base your decisions, interpretations and conclusions on your observations and experience, but don't assume that they will apply to others.

Or even to you in the following season.

Evolution on The Apiarist

I've finally got round to revising the website listing the winter talks I offer. This includes my updated diary for late 2025 and early 2026. If you are interested in booking a talk next winter {{12}}, please take a look.

This site evolved over the last year and will change a bit more over the coming months. Like natural evolution, the changes are generally rather minor. Unlike natural evolution, the changes are not random and - where possible - most have been tested 😉.

- Sponsors will receive an additional newsletter - about every 2-3 weeks - that I've been trialling as 'BeeMusings' but which will now be brought 'in house' and listed on the website along with the regular weekly posts. These new posts will consist of single-topic, shorter articles and will incorporate the irregular Bees in the News posts. The latter were difficult to write - linking together disparate topics and keeping the content timely proved more challenging than I expected. This will increase the total sponsor-specific posts to ~50%.

- The cost of monthly, but not annual, sponsorship will be increased in April 2024 to reflect the Stripe processing fees I pay. The majority (>85%) of sponsors pay annually and, in due course, I will review whether to retain a monthly option.

- Sponsors should now receive a renewal reminder a week or so before renewal is due (I don't have a way of testing this).

- As briefly mentioned last week, I'm going to start a regular (~6 monthly) purge of inactive subscribers. If you receive, but never open, the weekly emails (or sign in to the site and read posts) I will stop sending them to you. After a further 6 months I will delete your membership. There are costs - £££ for email volume and in management time - associated with moribund accounts. I you're reading this as an emailed newsletter, or are a sponsor (Thank you!), this will never apply to you 😄.

- If I know what I'm going to write about next week - and I sometimes don't - I'll mention it at the end of the post.

Happy New Year

Next week ...

Bees with magnetic personalities, or something like that.

Sponsor to The Apiarist

It's unlikely that this post helped or inspired your beekeeping, though you never know. Nevertheless, there's a back-catalogue of hundreds of others that might, and an increasing number (see above) that are for sponsors only. Please consider sponsoring The Apiarist to support publication and the time spent researching and writing the posts.

Coffee is also always welcome 😄 and please spread the word to your friends and contacts via social media, email, billboard or carrier pigeon.

Thank you

{{1}}: That's laboratory, not lavatory ... a joke that doesn't work because the emphasis in the two words differs; lab-oratory vs lavat-ory. "Don't give up the day job".

{{2}}: In summer they often fly much further away with the corpses, but I rarely see this happening in winter. Of course, in the winter I rarely loiter in the cold apiary for longer than needed 😉.

{{3}}: Which involves the combination of β-ocimene and oleic acid produced by dead/dying/decaying pupae.

{{4}}: Been there, done that.

{{5}}: And there's a post from 2020 on the same topic.

{{6}}: European ... V. crabro, but hopefully not the yellow-legged hornet V. velutina.

{{7}}: And keeping hive records has been a previous recommendation for a resolution, and one likely to be beneficial if kept.

{{8}}: Though you can also access a digital copy via Project Gutenberg.

{{9}}: Commonly ascribed to Gilbert Doolittle in 1846, but - as discussed by Michael Bush - probably dating back to Nicol Jacobis in 1568!

{{10}}: I'm conveniently ignoring the technology involved ... bits of wood nailed together vs. intricate micro-electronics, optics and readily-outdated software.

{{11}}: That's a relatively uninformed guess.

{{12}}: I've been fully-booked for early 2025 since last summer.

Join the discussion ...