Provenance

This is a follow-on from the post last week about the adulteration of honey. For those of you who gave up reading midway through those 3800+ words the abridged version goes something like this.

80-90% of the honey consumed in the UK is imported. A very significant proportion of this imported honey originates, directly or indirectly, from China. When tested, about 75% of Chinese honey contains markers of adulteration i.e. it’s not honey. All tested honey exported from the UK was considered adulterated.

Most Honey is ‘pHoney’.

This ‘pHoney’ is largely what consumers are purchasing. Their experience influences their expectations of what honey is.

If they are used to a sickly sweet, golden coloured syrup in a squeezy bear, they are unlikely to be tempted by your delicate pale, soft-set mix containing 20% heather, or your zesty lime honey.

Of course, if they are used to the squeezy bear contents they might not like your honey.

But what about someone wanting to try something new, or to purchase honey as a gift?

Or who wants to purchase truly ‘local’ honey?

Someone who might not normally spend £9 on a jar of honey?

Or who just wants to find out more about the honey they have just purchased?

Read on.

Local or not?

I’d argue that there are broadly four geographically defined ‘types’ of honey:

- Global honey where the contents originate from somewhere else and there’s little or no pretence about the origin. This is the stuff that has no mention of the UK on the jar, and probably doesn’t mention anywhere specific by name.

- Global honey masquerading as something more local. Tesco’s Stockwell & Co.” honey perhaps. The name sounds English, but the contents are Chinese. This honey is 75 p a jar. However, there is a lot of very English sounding – or looking – honey selling for at least £5 a jar {{1}} which has never been near a UK bee. Look at the label and, hidden away in tiny print are the words ”Produce of EU and non-EU countries”.

- National honey. These jars are labelled “Produce of UK” (or Scotland, England, Wales etc.) but it’s sold everywhere. It’s only ‘local’ if you’re defining things at the level of individual countries. I see a lot of this honey for sale in Scotland, prepared by one or two of the big producers or packers. The labels tend to be rather generic – up here, tartans, heather etc. – and they’re probably perfectly good honeys. But they’re usually not local.

- Local honey. We could argue what local means. Three miles, thirty miles? I don’t know, don’t care and don’t think it matters a lot. The point is that it is honey clearly associated with a single location. The provenance of the honey is known.

There’s probably a fifth type; ‘local’ or ‘localish’ honey being sold elsewhere, like New Zealand Manuka (though lots of this is also pHoney).

Caveats

I should add that all of the above assumes that:

- it really is honey and not syrup masquerading as honey (and re-read the post from last week to be reminded of the scale of this type of fraud).

- if there is a country of origin indicated then it is the actual country that the honey is from. Remember that there are all sorts of underhand practices where honey is shipped via third countries or incorrectly labelled. Prosecutions have previously been successfully brought against companies importing Chinese honey mislabelled as originating from Malaysia, Mongolia, Thailand, or Vietnam.

There’s probably also a ‘type 2.5’; a smallish percentage of national honey in a jar otherwise filled with honey from somewhere else entirely. There may be others as well.

Provenance

Provenance has two meanings that could be considered relevant to honey.

Firstly, it means ’coming from a particular source or origin’ and may have historically implied ‘good breeding or gentility’.

Secondly, and usually applied to works of art or antiques, it means a ’history of ownership, used as a guide to authenticity or quality’.

We’ll ignore the ‘good breeding’ bit … but the other two fit honey rather well.

Local honey should have a clearly defined origin or source and if there’s also evidence of authenticity or quality then all the better.

How can you demonstrate this when labelling and selling your honey?

In the discussion below I’m only going to be referring to the geographic origin of the honey, rather than the type of honey e.g. wildflower, oil seed rape, clover. There are regulations on what words (and images) are allowed or disallowed, and the proportion a particular nectar must be present at for a honey to carry a specific name.

Labels

I think that labelling honey (or, for that matter, any foodstuff) is a bit of an art.

Doing it well certainly is and I’ve seen some gorgeous honey labels.

I’ve also seen some beautifully minimalist designs that flagrantly breach most of the honey labelling regulations, stunning full-colour wraps that entirely obscure the frosted jar contents and sexy transparent labels that are nearly impossible to read under shop lighting.

There are also the ‘olde-worlde’ labels – usually adorned with a skep – designed to look like something from the 1870’s (despite the price-tag and the weight in grams), or rolling vistas of purple heather moors on a jar of ‘raw’ urban honey.

In all honesty, labelling honey is not an art I’m well-versed in, so I’d strongly recommend you, a) take any of the following comments with a pinch of salt, b) employ a professional, and c) consider carefully other ‘competing’ honeys where yours will be displayed.

I’m also colourblind, so any recommendations I make, or preferences I express, usually need to be considered with that in mind … so I won’t.

Instead I’ll stick to some of the information provided on the label.

Information that helps the (potential) customer determine the provenance of the honey.

The country of origin

Whilst not necessarily ’front and centre’ I do think the country of origin should be clearly visible with the jar on the shelf.

One of the things you’ll notice about most of the blended honeys is that those weasel words ’Blend of EU and non-EU honeys’ will be hidden round the sides or back of the jar, well away from direct view.

Tesco’s Stockwell & Co. honey is a perfect example of this. The visible label – assuming the honey isn’t in your hand, or stood back to front on the shelf – just contains the dated appearance ’Since 1924 … T.E. Stockwell & Co’ branding {{2}}. The country of origin is hidden around the side/back.

So, since all of my honey is produced in Scotland, I clearly label my jars ’Produce of Scotland’.

Why Scotland and not the United Kingdom?

Mainly because Scotland is definitely a country, but also because a) many of my customers are Scottish and they’d prefer to buy Scottish produce rather than something labelled ‘United Kingdom’, b) I sell through outlets frequented by tourists and since they’ve chosen to visit this wonderful country they also prefer to purchase something that clearly originates here, and c) I’m not entirely sure whether the United Kingdom (or Great Britain) is a country or a state, or a political union … or likely to survive if Scotland and Wales and Cornwall and Yorkshire gain independence 😉 .

I’m proud to produce Scottish honey and I’m sure it helps sales, so I make sure it’s clearly visible.

Location, location, location

Unless you live in Liechtenstein or Tuvalu the country of origin doesn’t provide customers with much help in pinpointing where the honey is from.

Is it local honey or was it produced and jarred dozens – or hundreds – of miles away?

In the supermarkets you’ll see serried rows of jars of ’English Honey’. The same jars and labels are in every branch, whether it’s Truro or Tyneside. This stuff is packed and bought by the tonne. I’m sure the honey is just fine, and some customers welcome the certainty of being able to buy exactly the same stuff, wherever they are.

Many smaller scale beekeepers also label their honey in a similar way … ’English Wildflower Honey’ or ’Scottish Heather Honey’. These, and the supermarket honeys described above, are probably the ‘type 3’ defined above.

If the honey already states ’Produce of England’ it seems tautological to then label the honey ’English Honey’ {{3}}.

However, the honey labelling regulations allow regional information to be provided as part of the name of the honey. The precise wording is:

The product name of a relevant honey may be supplemented by information relating to its regional, territorial or topographical origin but no person may trade in a relevant honey for which such supplemental information is provided unless the product comes entirely from the indicated origin.

I see this as an opportunity to both provide a useful geographic focus for the customer and make it distinct from the other honey that it shares the shelf (i.e. competes) with.

I therefore label my honey with the name of the closest village or small town in Fife to where it is produced.

Local honey

Fortunately these place names are recognisable – in the case of St Andrews both nationally and internationally – and they don’t clash with other ‘local’ honey sold by the same farm stores, garden centres or local artisan cafes.

Equally fortunately, neither of the names I use are rude or funny. If I had hives in Boghead, Ayrshire or Ugley, Essex I’d choose the name of a different location {{4}}.

I get a lot of requests for ‘local’ honey.

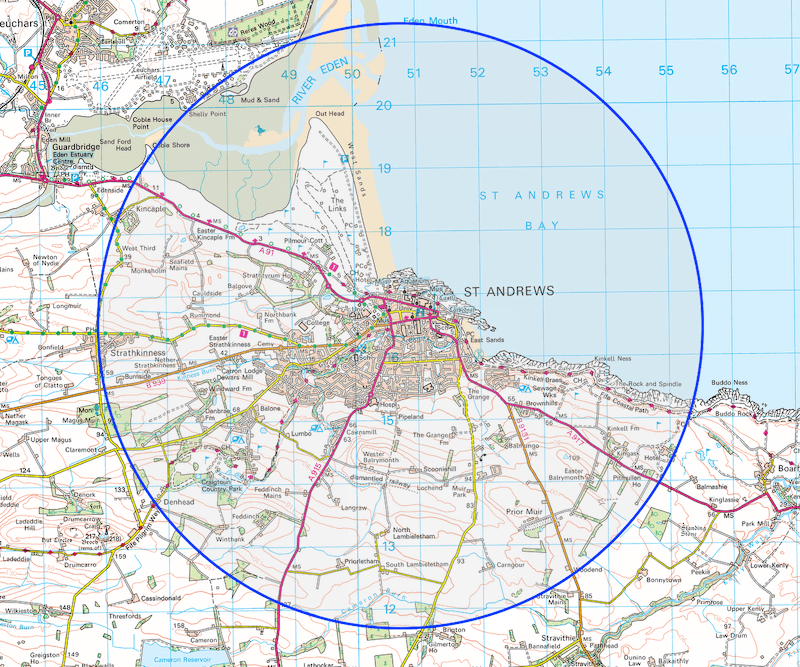

As I stated above, I’m never entirely sure what local means {{5}}.

It has to mean further than a bee can forage; the distribution of apiaries, beekeepers and outlets selling honey means that it’s rare the honey is that local.

I sell from one shop where the bees are within 200 metres of the shelves on which the honey is displayed, but that’s unusual. For the rest, with one exception, all of my honey is sold within about 20 miles of the apiaries in which it is produced.

This seems to work well. The place names are recognisable, don’t clash with other honeys, and I don’t produce such vast amounts that I need to find more distant locations to sell from. If I did, I might choose to use a ‘larger’ regional name, or another recognisable location, for example a historic province …

“… regional, territorial or topographical …”

… gives you quite a bit of flexibility.

Further information

When I used to sell honey ’from the door’ I’d put a sign out in the road and spend 25 minutes discussing bees, foraging distances, hay fever and stings for every jar of honey I sold.

I daren’t do the maths, but my ‘earnings’ were well under the minimum wage.

Lots of the customers wanted to know more about where the bees were, what they foraged on, whether it was a good area for bees etc. Assuming I wasn’t trying to meet a work deadline I was very happy to answer the questions and met some interesting people.

However, I now live 140 miles away and cannot sell ’from the door’, but I assume that at least some customers are still interested in the answers to these questions.

Some outlets have a social media presence and advertise the local produce they sell, others provide handwritten labels on the shelf that provides some of this additional information.

But many don’t.

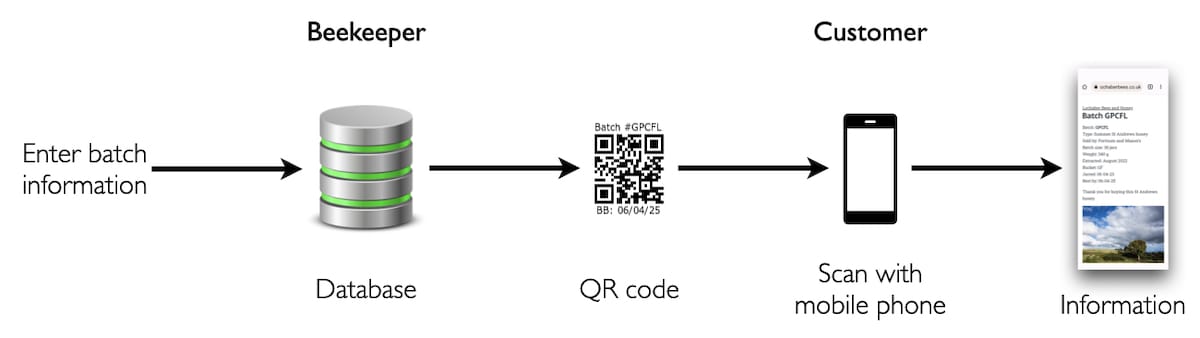

I therefore developed a system that enables me to provide further information to customers in conjunction with the unique batch number(s) my jars carry.

Most customers never access this, they just scoff the honey and return to buy another jar 🙂 .

However, those that do want more information can find it online by typing in a web address, or scanning a barcode on the jar.

The system I use is not dissimilar to that used by some of the Manuka honey producers in New Zealand. It’s homegrown, a little ragged round the edges (though the end user never sees these rough bits), but seems to work reasonably well. Customers who want information can easily find it, whereas those that do not aren’t offered jars with large unsightly descriptive labels.

Batch numbers

Every jar of honey I sell carries a batch number. These are 5 characters and/or digits long, unique and created at random. I only use a subset of the characters A-Z and digits 0-9 to avoid those that look ambiguous (e.g. 1 and I, S and 5), but this still provides me with over 17 million potential variants.

Honey is jarred to order. Each batch jarred is therefore assigned a different batch number, recorded automagically into a database together with the jar size, number in the batch, outlet (Fred’s deli, Private sales, Glenrothes farmers market, etc.), apiary, bucket number and date (of jarring and best before).

Batches are usually 12-60 jars in total, depending upon the volume of the jars (and the size of the bucket).

If there’s ever an issue with a particular batch I can therefore identify it unambiguously – when/where it was produced, extracted, jarred, sold etc.

Equally importantly, if a customer wants to know more about the honey they’ve just purchased (or are about to purchase) they can look up the provenance of the honey by visiting a website.

Typing or scanning

Inevitably the typeface used on a label is rather small, particularly because I use relatively small labels so as to not obscure the contents of the jar. Nevertheless, a web address such as https://lochaberbees.co.uk/GPCFL isn’t too onerous to type if the customer has access to a computer.

And, anyone with a smartphone, has access to a computer.

However, it might be a bit much to expect them to stand in the aisle using their thumbs to type the address into their phone before purchase.

Which is where a QR code comes in very useful.

Go on … scan me!

QR codes are two dimensional barcodes that can be scanned using a smartphone camera. The information within the QR code is limited but is more than enough encode a web address. What’s more, the code includes redundancy for error correction, so can still be successfully scanned if damaged or only partly legible.

Finally, most smartphone cameras are smart enough to know that a QR code containing a web address should redirect the user, via their web browser, to that web address.

Using a combination of Kentaro Fukuchi’s qrencode and the awesome imagemagick {{6}} I create and edit a QR code, appending the best before date and batch number. This graphic can then be printed onto a small label for the reverse of the jar.

Inclusion of this information on a separate label means that the standard jar label can be a little more generic, focusing solely on the contents and location information, together with the necessary contact details.

Automagic

Almost all of the above is semi-automated. A perl script generates the batch number, checks it is unique, updates the database and produces the edited QR code.

When the code is scanned – if it is scanned – another perl script updates the database to keep a count of whether a particular batch has been scanned (no other information is recorded) and then, seamlessly, redirects the customer to a web page that displays information about the honey. Because of the configuration of my website, the latter is generated from a template rather than being built ‘on the fly’ from the database.

(Relatively) simples.

It’s worth noting that QR codes are a much more effective way of ‘interacting’ with potential customers. When my thermal printer recently packed up, the typed URL on the label generated fewer visits to the page describing the honey.

’From the beekeeper to the customer’

Supermarkets, challenged when shown to be selling adulterated honey, claimed they could trace the product ‘from the beekeeper to the customer’. I wrote last week that I found this unlikely {{7}}. Realistically, what are the chances of identifying the beekeeper who supplied the honey in 10,000 squeezy bears imported in a large batch of 300 kg drums, before jarring by a UK packer?

Less than zero?

But using the approach described above, my customers can see photographs of the region where the apiaries are located, a map showing the approximate area over which they forage, details of the pollen content (if I’ve got it from the National Honey Monitoring Scheme) or the crops in the neighbourhood. I can include a description of honey harvesting and preparation, crystallisation or pretty much anything else I want.

Local honey

Obviously I don’t write this for each batch of honey jarred. I have two ‘production’ apiaries and produce two annual honey crops, so a few different paragraphs of text and a handful of photos are sufficient and used to populate the template files from which the web pages are generated.

A customer wanting to know more about the ‘local’ honey sold in a store only needs to scan the code and they have more than enough information in front of them. If a customer is looking for local honey and has a choice between a jar of ‘Scottish Honey’, a jar of ‘Fife Honey’ and a jar of my honey, they can quickly tell exactly where mine originates.

And more.

They may still buy a different jar, but at least they make an informed decision.

localhoney.theapiarist.org

Many years ago I taught myself a heady mix of computer programming, SQL databases and web servers. I used it for research, manipulating hundreds of gigabytes of biological sequence data {{8}} to produce a series of hugely influential little-read papers on viral RNA structure {{9}}.

The same mix of technologies now provides customers and shop keepers with information on the provenance of the honey they are buying/selling.

I suspect I know which is likely to be more useful 😉 .

I have to produce batch numbers and best before dates for my honey {{10}}. The system is scalable. I could use it for thousands of jars or hundreds of batches, or more than one beekeeper. When I finally produce enough west coast heather honey to sell I just need to prepare another page template and it can be automagically populated with the relevant information.

Does it increase sales?

Who knows? I certainly don’t.

The day to day, week to week and month to month variation in sales is too noisy. I’d need to produce loads of jars labelled like this, and loads without these labels, and do some sort of controlled test.

I’m happy enough to provide the information. It’s there if customers want it.

And, unlike the supermarkets, it does provide a direct link from the beekeeper to the customer.

And, on a related matter …

National Bee Unit … thanks for nothing 😉

While we’re on the subject of websites … the National Bee Unit (NBU) have recently updated their site. Unfortunately, in doing so they have changed every single web page address (URL).

OK, these things happen … there’s an easy solution.

The system demonstrating the provenance of my honey (described above) makes use of a process inbuilt in all web servers called ‘redirection’. Essentially, you enter one URL and the web server redirects you to another one. It’s very simple, blisteringly fast and makes for a seamless and pleasant user experience.

Except the National Bee Unit have not provided any redirection from the old URL to the new one. As a consequence, every single link on this website to the NBU (and probably every single link on the internet to pages at the NBU) no longer work.

Genius … not 🙁 .

Why provide the information and then make it more difficult to find?

At some point I’ll therefore have to manually find the linked page on the new site and edit all the links.

Or perhaps I’ll simply delete them all …

{{1}}: Unless otherwise specified all prices quoted are for 340 g jars.

{{2}}: A Tesco trademark, and the name of individual – Thomas Edward Stockwell – that Jack Cohen, the founder of Tesco first bought tea from (in 1924) … and named the supermarket after.

{{3}}: Remember, the latter does not allow you to omit the former.

{{4}}: There are some fantastic place names in the UK. Since I try and appeal to a family readership I’ve avoided some of the more glaringly unpleasant ones, though I can’t stop myself from mentioning Shitterton in Dorset, Wetwang in East Yorkshire and Twatt in Orkney. Oh how we I laughed!

{{5}}: In this context, or when talking about local bees.

{{6}}: Where awesome = complex.

{{7}}: Actually, I said I thought it was a ’porky pie’.

{{8}}: Before ’big data’ was big news.

{{9}}: Insomniacs start here …

{{10}}: Yes, I know these can be combined, but having them separate is more useful to me.

Join the discussion ...