Reducing winter losses

A guaranteed way of reducing winter losses is to only overwinter colonies that are strong and healthy. Although colony losses can occur for several reasons (e.g. starvation) researchers in Switzerland have shown that high levels of the parasitic mite Varroa and deformed wing virus (DWV), which the mite transmits, are the primary cause of overwintering colony losses. It is therefore important to minimise mite numbers in the colony in early autumn, preferably by treating with a miticide early enough for the queen to have time to lay up more frames before the weather gets too cold. Many mite treatments (e.g. Apiguard and MAQS) stop queens laying.

I completed Apiguard treatment of my colonies by mid-September but noticed that one still contained lots of bees showing the characteristic symptoms of DWV infection – atrophied wing development, stunted abdomens and a generally dark coloration. In the photograph (right) there are at least 5 bees visible with these symptoms, one of which also has a phoretic mite attached (lower right hand corner). This colony had failed to build up after a mid-season setback. It was only taking limited amounts of fondant down and the flying bees were bringing back only small amounts of pollen (in marked contrast to neighbouring colonies that – now the Apiguard is off – are piling in huge amounts of pollen for the winter). There were also signs of sacbrood virus which often requires re-queening to eradicate. The queen was still laying, but there was only a frame and a half of sealed brood.

At this stage in the season there is no real chance this colony could build up sufficiently to overwinter successfully. It’s not simply dependent upon the size of the colony, it’s also the vigour. After all, it’s reasonably straightforward to overwinter Apidea or Kieler mini-nucs with a bit of care. These have far fewer bees present than the colony photographed above.

Shake them out …

If the colony had been healthy, but small, I would have united it with another over newspaper. However, I wanted to minimise exposure of other colonies to the brood so instead removed the queen, moved the colony to another corner of the apiary and shook all the bees out. The healthy flying bees should be able to get accepted by another colony. The symptomatic bees would be lost. Although there was a risk that bees carrying phoretic mites would get back to other colonies I carefully checked the frames before shaking them out and saw almost no mites. In due course I’ll treat these remaining colonies with oxalic acid. I subsequently uncapped a frame or so of brood and found almost 50% of capped pupae were mite-associated.

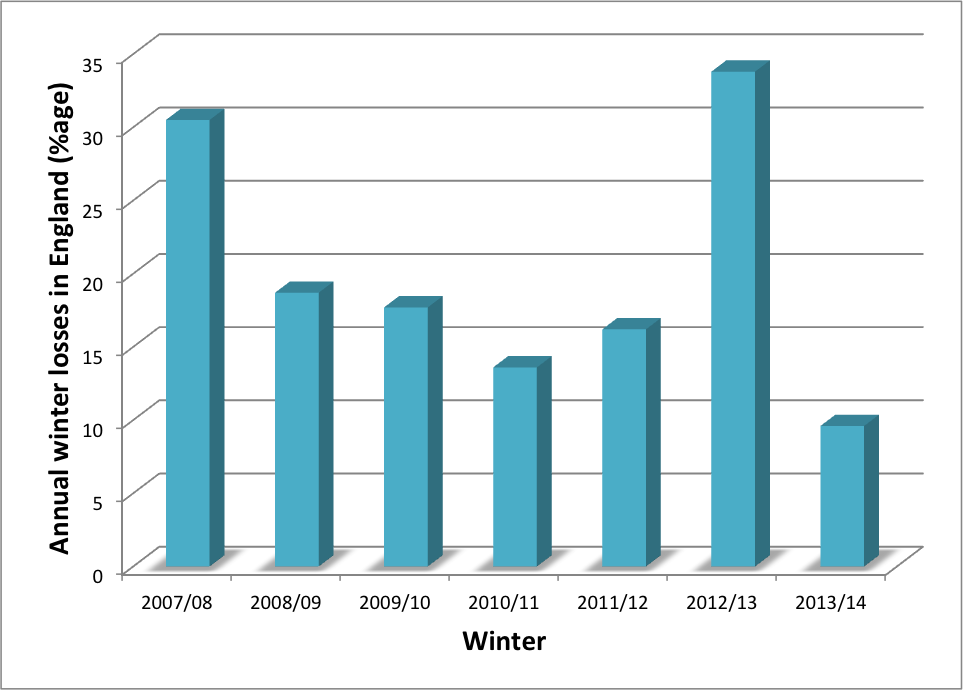

Figures collected and published by the BBKA indicate that, on average in England, ~20% of colonies are lost each winter. In particularly hard winters, such as 2012/13, losses can be significantly higher than this, reaching over 50% in certain regions of the country.

Annual colony losses

Aside from ensuring adequate stores are present in late autumn, with hives in good condition to provide protection from the elements, the best way to minimise overwintering losses is to not try and overwinter weak or diseased colonies. Sometimes you have to be cruel to be kind …

Join the discussion ...