Aristotle's hairless black thieves

Almost every article or review on chronic bee paralysis virus {{1}} starts with a reference to Aristotle describing the small, black, hairless ‘thieves‘, which he observed in the hives of beekeepers on Lesbos over 2300 years ago {{2}}.

Although Aristotle was a great observer of nature, he didn’t get everything right.

And when it came to bees, he got quite a bit wrong.

He appreciated the concept of a ‘ruling’ bee in the hive, but thought that the queen was actually a king {{3}}. He also recognised different castes, though he thought that drones (which he said “is the largest of them all, has no sting and is stupid”) were a different species.

He also reported that bees stored noises in earthenware jars (!) and carried stones on windy days to avoid getting blown away {{4}}.

However, over subsequent millenia, a disease involving black, hairless honey bees has been recognised by beekeepers around the world, so in this instance Aristotle was probably correct.

Little blacks, maladie noire, schwarzsucht

The names given to the symptomatic bees or the disease include little blacks or black robbers in the UK, mal nero in Italy, maladie noire in France or schwarzsucht (black addiction) in Germany. Sensibly, the Americans termed the disease hairless black syndrome. All describe the characteristic appearance of individual diseased bees.

Evidence that the disease had a viral aetiology came from Burnside in the 1940’s who demonstrated the symptoms could be recapitulated in caged bees by injection, feeding or spraying them with bacterial-free extracts of paralysed bees. Twenty years later, Leslie Bailey isolated and characterised the first two viruses from honey bees. One of these, chronic bee paralysis virus (CBPV), caused the characteristic symptoms described first by Aristotle {{5}}.

CBPV causes chronic bee paralysis (CBP), the disease first described by Aristotle.

CBPV infection is reported to present with two different types of symptoms, or syndromes. The first is the hairless, black, often shiny or greasy-looking bees described above {{6}}. The second is more typically abnormal shivering or trembling of the wings, often associated with abdominal bloating {{7}}. These bees are often found on the top bars of the frames during an inspection. Both symptoms can occur in the same hive {{8}}.

CBP onset appears rapid and the first thing many beekeepers know about it is a large pile (literally handfuls) of dead bees beneath the hive entrance.

It’s a distressing sight.

Despite thousands of bees often succumbing to disease, the colony often survives though it may not build up enough again to overwinter successfully.

BeeBase has (had ... all links at the NBU were broken during their website reorganisation ... try searching for CBPV there) photographs and video of the typical symptoms of CBPV infection.

Until recently, CBP was a disease most beekeepers rarely actually encountered.

Emerging and re-emerging disease

I’ve got a few hundred hive year’s worth {{9}} of beekeeping experience but have only twice seen CBP in a normally-managed colony. One was mine, another was in my association apiary a few years later.

A beekeeper managing 2 to 3 colonies might well never see the disease.

A bee farmer running 2 to 3 hundred (or thousand) colonies is much more likely to have seen the disease.

As will become clear, it is increasingly likely for bee farmers to see CBP in their colonies.

Virologists define viral diseases as emerging if they are new in a population. Covid-19, or more correctly SARS-CoV-2 (the virus), is an emerging virus. They use the term re-emerging if they are known but increasing in incidence.

Ebola is a re-emerging disease. It was first discovered in humans in 1976 and caused a few dozen sporadic outbreaks {{10}} until the 2013-16 epidemic in West Africa which killed over 11,000 people.

Often the terms are used interchangeably.

Sporadic and rare … but increasing?

Notwithstanding the apparently sporadic and relatively rare incidence of CBP in the UK (and elsewhere; the virus has a global distribution) anecdotal evidence suggested that cases of disease were increasing.

In particular, bee farmers were reporting increasing numbers of hives afflicted with the disease, and academic contacts overseas involved in monitoring bee health also reported increased prevalence.

Something can be rare but definitely increasing if you’re certain about the numbers you are dealing with. If you only have anecdotal evidence to go on you cannot be certain about anything very much.

If the numbers are small but not increasing there are probably other things more important to worry about.

However, if the numbers are small but definitely increasing you might have time to develop strategies to prevent further spread.

Far better you identify and define an increasing threat before it increases too much.

With research grant support from the UKRI/BBSRC (the Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Research Council) to the Universities of Newcastle (Principle Investigator, Prof. Giles Budge) and St Andrews, and additional backing from the BFA (Bee Farmers’ Association), we set out to determine whether CBPV really was increasing and, if so, what the increase correlated with (if anything).

This component of the study, entitled Chronic bee paralysis as a serious emerging threat to honey bees, was published in Nature Communications last Friday (Budge et al., [2020] Nat. Comms. 11:2164 https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-020-15919-0).

The paper is Open Access and can be downloaded by anyone without charge.

There are additional components of the study involving the biology of CBPV, changes in virus virulence, other factors (e.g.environmental) that contribute to disease and ways to mitigate and potentially treat disease. These are all ongoing and will be published when complete.

Is chronic bee paralysis disease increasing?

Yes.

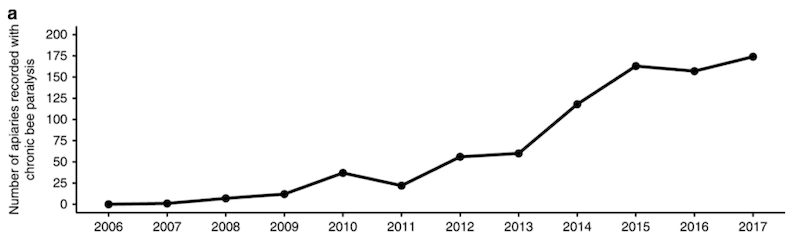

We ‘mined’ the National Bee Units’ BeeBase database for references to CBPV, or the symptoms associated with CBP disease. The data in BeeBase reflects the thousands of apiary visits, either by call-out or at random, by dedicated (and usually overworked) bee inspectors. In total we reviewed almost 80,000 apiary visits in the period from 2006 to 2017.

There were no cases of CBPV in 2006. In the 11 years from 2007 to 2017 the CBP cases (recorded symptomatically) in BeeBase increased exponentially, with almost twice as much disease reported in commercial apiaries. The majority of this increase in commercial apiaries occured in the last 3 years of data surveyed.

BeeBase covers England and Wales only. By 2017 CBPV was being reported in 80% of English and Welsh counties.

During the same period several other countries (the USA, several in Europe and China) have also reported increases in CBPV incidence. This looks like a global trend of increased disease.

But is this disease caused by CBPV?

It should be emphasised that BeeBase records symptoms of disease – black, hairless bees; shaking/shivering bees, piles of bees at the hive entrance etc.

How can we be sure that the reports filed by the many different bee inspectors {{11}} are actually caused by chronic bee paralysis virus?

Or indeed, any virus?

To do this we asked bee inspectors to collect samples of bees with CBPV-like symptoms during their 2017 apiary visits. We then screened these samples with an exquisitely sensitive and specific qPCR (quantitative polymerase chain reaction) assay.

Almost 90% of colonies that were symptomatically positive for CBP were also found to have very high levels of CBPV present. We are therefore confident that the records of symptoms in the historic BeeBase database really do reflect an exponential increase of chronic bee paralysis disease in England and Wales since 2007.

Interestingly, about 25% of the asymptomatic colonies also tested positive for CBPV. The assay used was very sensitive and specific and allowed the quantity of CBPV to be determined. The amount of virus present in symptomatic bees was 235,000 times higher than those without symptoms.

Further work will be needed to determine whether CBPV is routinely present in similar proportions of ‘healthy’ bees, and whether these go on and develop or transmit disease.

Disease clustering

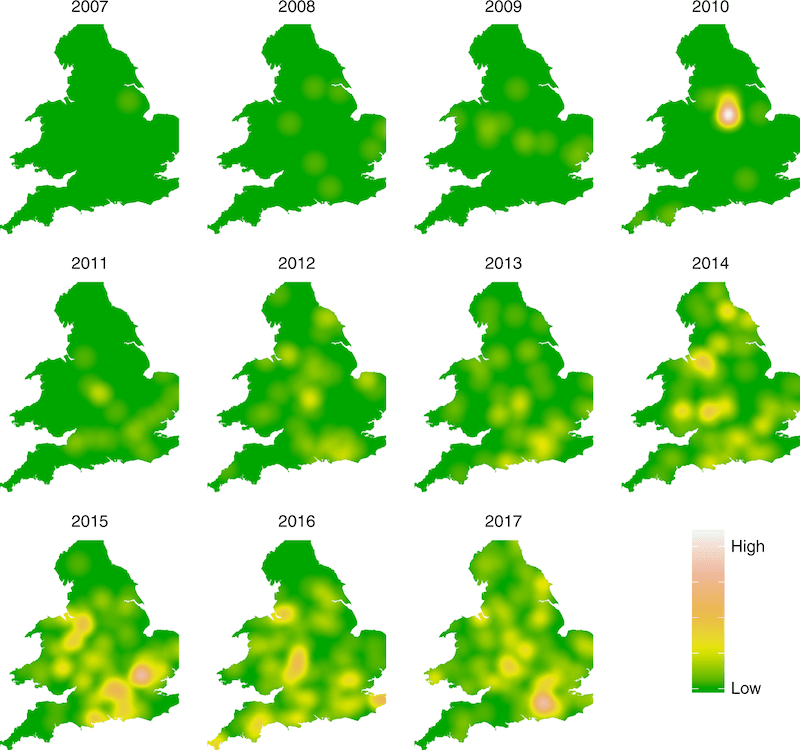

Using the geospatial and temporal (where and when) data associated with the BeeBase records we investigated whether CBPV symptomatic apiaries were clustered.

For example, in any year were cases more likely to be near other cases?

They were.

Across all years of data analysed together, or for individual years, there was good evidence for spatial clustering of cases.

We also looked at whether cases in one year clustered in the same geographic region in subsequent years.

They did not.

This was particularly interesting. It appears as though there were increasing numbers of individual clustered outbreaks each year, but that the clusters were not necessarily in the same geographic region as those in previous or subsequent years.

The disease appears somewhere, increases locally and then disappears again.

Apiary-level disease risk factors

The metadata associated with Beebase records is relatively sparse. Details of specific colony management methods are not recorded. Local environmental factors – OSR, borage, June gap etc. – are also missing. Inevitably, some of the factors that may be associated with increased risk are not recorded.

A relatively rare disease that is spatially but not temporally clustered is a tricky problem for which to define risk factors. Steve Rushton, the senior author on the paper, did a sterling job of analysing the data that was available.

The two strongest apiary-level factors that contributed to disease risk were:

- Commercial beekeeping – apiaries run by bee farmers had a 1.5 times greater risk of recording CBP disease.

- Importing bees – apiaries which had imported bees in the two preceding years had a 1.8 times greater risk of recording CBP disease.

Bee farming is often very different from amateur beekeeping. The colony management strategies are altered for the scale of the operation and for the particular nectar sources being exploited. For example, colonies may already be booming to exploit the early season OSR. This may provide ideal conditions for CBPV transmission which is associated with very strong hives and/or confinement.

Bee imports does not mean disease imports

There are good records of honey bees imported through official channels. This includes queens, packages and nucleus colonies. Between 2007 and 2017 there were over 130,000 imports, 90% of which were queens.

An increased risk of CBP disease in apiaries with imported bees does not mean that the imported bees were the source of the disease.

With the data available it is not possible to distinguish between the following two hypotheses:

- imported honey bees are carriers of CBPV or the source of a new more virulent strain(s) of the virus, or

- imported honey bees are susceptible to CBPV strain(s) endemic in the UK which they were not exposed to in their native country.

There are ways to tease these two possibilities apart … which is obviously something we are keen to complete.

All publicity is good publicity …

… but not necessarily accurate publicity 🙁

We prepared a press release to coincide with the publication of the paper. Typically this is used verbatim by some reporters whereas others ask for an interview and then include additional quotes.

Some more accurately than others 🙁

The Times, perhaps reflecting the current zeitgeist, seemed to suggest a directionality to the disease that we certainly cannot be sure of:

Its sister publication, The Sun, “bigged it up” to indicate – again – that bees are being wiped out.

And the comments included these references to the current Covid-19 pandemic:

- “Guess its beevid – 19. I no shocking”

- “It’s the radiation from 5g..google it”

- “Local honey is supposed to carry antibodies of local virus and colds – it helps humans to eat the stuff or so they say. So it could be that the bees are actually infected by covid. No joke.“

All of which I found deeply worrying, on a number of levels.

The Telegraph also used the ‘wiped out’ reference (not a quote, though it looks like one). They combined it with a picture of – why am I not surprised? – a bumble bee. D’oh!

The Daily Mail (online) had a well-illustrated and pretty extensive article but still slipped in “The lethal condition, which is likely spread from imports of queen bees from overseas …”. The unmoderated comments – 150 and counting – repeatedly refer to the dangers of 5G and EMFs (electric and magnetic fields).

I wonder how many of the comments were posted from a mobile phone on a cellular data or WiFi network?

😉

Conclusions

CBPV is causing increasing incidence of CBP disease in honey bees, both in the UK and abroad. In the UK the risk factors associated with CBP disease are commercial bee farming and bee imports. We do not know whether similar risk factors apply outside the UK.

Knowing that CBP disease is increasing significantly is important. It means that resources – essentially time and money – can be dedicated knowing it is a real issue. It’s felt real to some bee farmers for several years, but we now have a much better idea of the scale of the problem.

We also know that commercial bee farming and bee imports are both somehow involved. How they are involved is the subject of ongoing research.

Practical solutions to mitigate the development of CBP disease can be developed once we understand the disease better.

Full disclosure:

I am an author on the paper discussed here and am the Principle Investigator on one of the two research grants that funds the study. Discussion is restricted to the published study, without too much speculation on broader aspects of the work. I am not going to discuss unpublished or ongoing aspects of the work (including in any answers to comments or questions that are posted). To do so will compromise our ability to publish future studies and, consequently, jeopardise the prospects of the early career researchers in the Universities of St Andrews and Newcastle who are doing all the hard work.

Acknowledgements

This work was funded jointly by BBSRC grants BB/R00482X/1 (Newcastle University) and BB/R00305X/1 (University of St Andrews) in partnership with The Bee Farmers’ Association and the National Bee Unit of the Animal and Plant Health Agency.

{{1}}: There aren’t that many …

{{2}}: And, as you can see, this one is no different.

{{3}}: A point not corrected for two millenia with the publication of Charls Butler’s Feminine Monarchie in 1634

{{4}}: Virgil repeated this a couple of hundred years later … perhaps Aristotle was referring to pollen.

{{5}}: The other virus was acute bee paralysis virus.

{{6}}: This is usually referred to as the Type 2 syndrome, but for continuity with the reference to Aristotle I’m describing it first.

{{7}}: The Type 1 syndrome.

{{8}}: And evidence from the 60’s shows they both involve the same virus at similar levels, so the different presentation must be due to variation in the bee, or additional factors.

{{9}}: Hives multiplied by beekeeper years.

{{10}}: Tragically killing up to a few hundred people in each.

{{11}}: Anyone who has seen a bee inspector at work will be aware of their skill, but disease description involves a level of subjective analysis which inevitably differs between individuals.

Join the discussion ...