Spring starvation

A very brief post this week to highlight the dangers of unseasonably warm weather early in the season. February 2019 has entered the record books as the first ‘winter’ month in which the temperature exceeded 20°C (on at least the 25th and 26th in the UK). It’s also been a record with the daily temperature (highs … we’ve had some hard frosts as well) exceeding the historic average daily temperature on almost every day of the month.

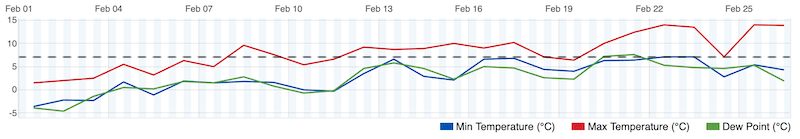

Even here in Fife on the East coast of Scotland, the weather has been very warm and sometimes even sunny. The graph above shows the daily maximum temperature compared to the monthly average (dashed line).

The contrast with this time last year is very striking. The big winter storm called Anticyclone Hartmut (aka the Beast from the East) arrived in the last week of February.

We had six foot deep snow drifts blocking the road to the village and there wasn’t a bee to be seen.

Crocus and snowdrop

Fast forward exactly 12 months and the bees are piling in the pollen and flying well for an extended period. Around here this early pollen probably comes from crocus, snowdrop, hazel and alder, perhaps with a bit of gorse as well which flowers throughout the season.

Brood rearing will have started in earnest. The large amounts of pollen being collected is a pretty good indicator that all is well in the hive, that the queen is starting to ramp up her egg laying rate and the numbers of hungry larvae are increasing.

There’s no need to open the hive to check for brood. Indeed, hive inspections (here at least) are probably at least 6 weeks away.

However, don’t ignore the colonies. The increase in brood rearing is a time when stores levels can quickly get critically low. There’s not a huge range of nectar sources about at the moment and the combination of a warm spell, increasing amounts of brood and a subsequent deterioration in the weather can rapidly result in colonies starving.

Hefting or a sneak peak

If you’ve been regularly hefting the hive to check its weight you should have a reasonable ‘feel’ for what it should be, and whether it’s significantly lighter. More accurately, but also more trouble, you can use luggage scales to record the week-by-week reduction over the winter.

It’s possible to determine whether there are sufficient – or at least some – stores by looking through a perspex crownboard at the tops of the frames.

Many of my hives went into the winter with the remnants of the autumn-fed fondant still present on the top bars. With a perspex crownboard it’s a trivial task to check if these stores have been used and – if they have – to heft the hive to see if they need more.

Fondant topups

Several hives have already had a fondant topup of about a kilogram placed directly onto the top of the frames. Alternatively, the hives with the Gruyere-like Abelo crownboards {{1}} get a fondant block slapped directly over the hole above the most concentrated seams of bees.

Fondant absorbs moisture from the atmosphere so you need to protect the faces of the fondant block not accessed by the bees. There are all sorts of ways to do this. A strong plastic bag with a slot or flap cut in the bottom is more than adequate.

Better still is to dole out the fondant into plastic food containers you’ve diligently saved all year. These are reusable, come in a variety of sizes and – ideally – are transparent. You can then easily see when and if the bees need a further topup.

I usually slice up a block of fondant and fill these food containers in midwinter, wrap them in clingfilm and carry them around in the back of the car for my occasional apiary visits. If a hive needs more stores I remove the clingfilm and simply invert the container over the bees.

Do remove the clingfilm! Bees tend to chew it up and drag it down into the brood nest, often embedding it into brace comb. It can be a bit disruptive during cool weather early-season inspections to remove it … hence the suggestion to use a strong plastic bag earlier.

Continued vigilance

Most of my hives will have had at least a kilogram of fondant by the end of February this year. One or two are likely to have had significantly more. I’ll keep a note of these in my records as – all other things being equal – I’d prefer to have frugal bees that don’t need fussing with over the winter.

As the days get longer and the season continues to warm the queen will further increase her laying rate. Until there are both dependable foraging days and good levels of forage there remains the chance of starvation.

Colonies are much more likely to starve in early spring than in the middle of a hard winter. If the latter happens it’s either due to poor winter preparation or possibly disease. However, if they starve in early spring it is probably due to unseasonably warm weather, a lack of available forage, increasing levels of brood and a lack of vigilance by the beekeeper.

Don’t delay!

If a colony is worryingly light don’t wait for a warm sunny day to feed them. Adding a block of fondant as described above takes seconds.

If a colony needs stores add it as soon as possible.

If it’s cold the bees will be reasonably lethargic and you may not even need to smoke them. I’ve only fired up the smoker once … to topup a colony of psychotic monsters ‘on loan’ from a research collaborator who shall remain nameless.

I managed to add the fondant without using the smoker but they then chased me across the field to thank me 🙁

{{1}}: Which are often not the Abelo hives for a variety of reasons, predominantly my poor organisation.

Join the discussion ...