Upstairs, downstairs?

There are two common hive manipulations that involve stacking two brood boxes on top of each other – the vertical split and uniting colonies. Should the queenright colony go on the top or bottom when uniting colonies over newspaper? What about when conducting a vertical split? Does it make a difference?

In the following discussion I’m assuming the colonies being stacked are originally in single brood boxes. This is so I don’t have to qualify how many boxes are involved every time. For convenience, let’s also assume that you are uniting a queenless and queenright colony, rather than getting into a discussion of the benefits or otherwise of regicide.

Uniting colonies

There are a number of methods to unite (merge) two colonies. The simplest, the most often taught during beginners courses and – in my view – the (almost) foolproof method if you are not in a rush is uniting over newspaper.

To unite over newspaper the roof and crownboard from one colony are removed and one or two sheets of newspaper are laid over the top bars of the frames. One or two small holes are made through the newspaper and the second brood box is placed on top. Replace the crownboard and roof. The only precaution that needs to be taken is to ensure there isn’t brace comb on the bottom of the frames of the top box – this would puncture the newspaper and allow the bees to mix too quickly. This is also why I stressed a small hole in the paper.

Over the next 24-48 hours the colonies slowly chew holes through the paper, allowing the bees to gradually mix. It’s best not to interfere for a few more days. One week after uniting the frames can be rearranged and the bees cleared down to a single box if needed.

What matters and what doesn’t when uniting?

You’ll read three bits of advice about uniting using the method described above:

- The queenright colony should be on the bottom.

- The weaker colony should go on the top.

- The colony moved should be at the top.

Frankly, I don’t think it makes any difference whether the queen is in the top or bottom box. I’ve done it either way many times and never noticed a difference in success rates (generally very high), or the speed with which shredded newspaper is chucked out of the hive entrance. I think you can safely ignore this bit of advice. I can’t even think of a logical explanation as to why it’s beneficial to have the queen in the bottom box. Can you? After uniting I usually find the queen in the top box a week later.

If colonies differ markedly in strength I do try and arrange the top box as the weaker one. I suspect this is beneficial as it stops the foraging bees from the strong hive trying to get out or return mob-handed, potentially overwhelming the weaker colony.

I think it’s also sensible to locate the moved colony at the top of the stack. I think forcing them to negotiate the bottom box encourages the foragers from the moved hive to reorientate to the new hive location.

Vertical splits

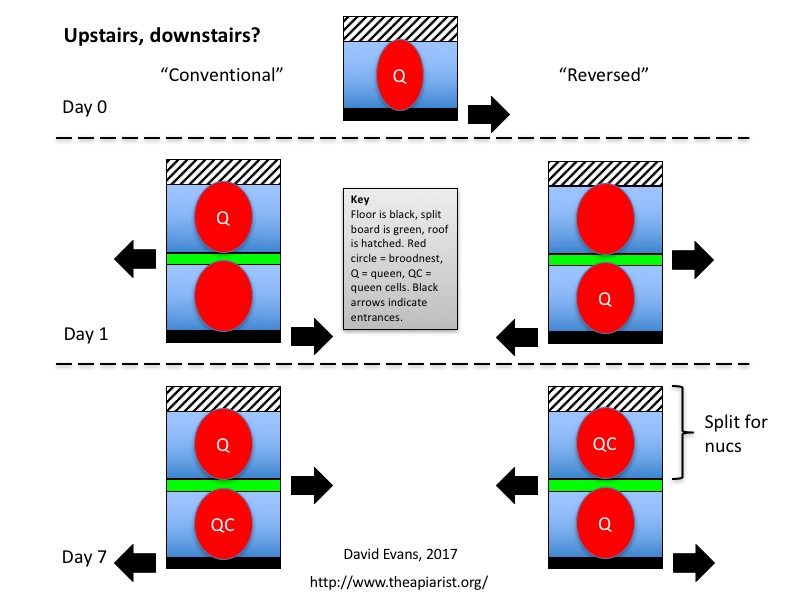

A vertical split is a hive manipulation that can be used as a swarm control strategy or as a means of ‘making increase’ – the beekeeping term for generating a new queenright colony. Whatever the reason, the practicalities are broadly the same and have been described in detail previously. Briefly, the queen and flying bees are separated vertically from the nurse bees and brood in two brood boxes with separate and opposing entrances.

As described, the queen is placed in the top box with the split board entrance facing the opposite direction to the original hive entrance. The logic here is that the flying bees are depleted from the queenright half of the colony, so both reducing the swarming impulse and boosting the strength of the half rearing a new queen.

After one week the hive is reversed on the stand – the front becomes the back and the back becomes the front. This results in depletion of flying bees from the queenless half, so reducing the chances of them throwing off a cast should multiple virgin queens emerge. Simultaneously the queenright half is strengthened, boosting its nectar-gathering capabilities.

The problem with vertical splits

Although I’m an enthusiastic proponent of the vertical split I acknowledge there are some drawbacks to the process.

Once there are supers involved things can get pretty heavy. Simply reversing a double brood box can be taxing for some (me included). I’m dabbling with building some floors and split boards with opposing entrances to try and simplify (or at least reduce the strain of) this aspect of the process.

A second problem is the need for subsequent inspections of the colonies. When used for making increase (or for that matter replacing the queen) nothing final can be done with the colonies until the new queen – reared in the bottom box – is mated and laying well.

Inspections

Of course, determining whether she is ‘mated and laying well’ involves splitting the boxes and carefully examining the lower colony. This inspection should probably take place about a month after the initial split (up to 16 days from egg to emerged queen, a week or so for her to get mated and a further week for the laying pattern to be established). Depending on colony strength, weather and the temperament of the colonies, this inspection might have to be conducted in a maelstrom of bees returning to the upper colony (which has had to be removed for the inspection). Perhaps not the most conducive conditions to find, mark and perhaps clip the new queen.

During the month that the new queen is being reared and mated there’s probably little or no need to inspect the queenright colony. They have ample laying room if you’ve provided them with drawn comb. If you gave them foundation only, or foundationless frames, they will likely need thin syrup if there’s a dearth of nectar. If you’re using a standard frame feeder this is a pretty quick and painless process.

Under the conditions described above I think it makes relatively little difference whether the original queen is ‘upstairs or downstairs’ at the outset of the split (though see the comments at the end on the entrance). However, having the new queen in the bottom box might dissuade you from inspecting too often or too soon – neither is to be encouraged where a new queen is expected.

More queens from more ambitious vertical splits

You can use a version of the vertical split to rear several queen cells. Rather than then reversing the colony and depleting the queenless half of bees you can use it to create a number of 2-3 frame nucs, each populated with a big fat ripe queen cell. In this way you can quickly make increase – trebling, quadrupling or perhaps quintupling the original hive number. The precise details are outside the scope of this article – which is already too long – but Wally Shaw covers it in his usual comprehensive manner (PDF) elsewhere.

For this you want to make the initial queenless half to be as strong as possible (to rear good queens). You also want it to be as easy to access as possible to facilitate checking on the development of the new queen cells. Under these conditions I think there’s good reason to start with the original mated queen ‘downstairs’.

A higher entrance

Remember that at the start of a vertical split, and for a couple of days after, bees will be exiting the rear entrance and returning to the ‘front’ of the hive to which they originally orientated.

If you decide to leave the original queen in the lower box this will necessitate reversing the hive at the very start of the process, then placing the split board entrance at the hive front. Bees cope well with this vertical relocation of a hive entrance. Sure, there’ll be a bit of milling about and general confusion, but they’ll very quickly adjust to a hive entrance situated about 25cm above the original one. In the original description of the vertical split they had to make precisely this adjustment at the 7 day hive reversal. It helps to try and restrict bees from accessing the underside of the open mesh floor during these hive reversals – for example with a simple plastic skirt (see above right).

In conclusion

Bees are pretty adaptable to the sorts of manipulations described above. Yes, there are certainly wrong ways to do things, but while being careful to avoid these, there are several different ways to manipulate the process to achieve the desired goal(s).

It’s worth thinking about the goal and the likely behaviour of the bees. Then have a go … what’s the worst that could happen?

Join the discussion ...