Cut your losses

The stats for winter losses in the UK, Europe and USA can make for rather sobering reading.

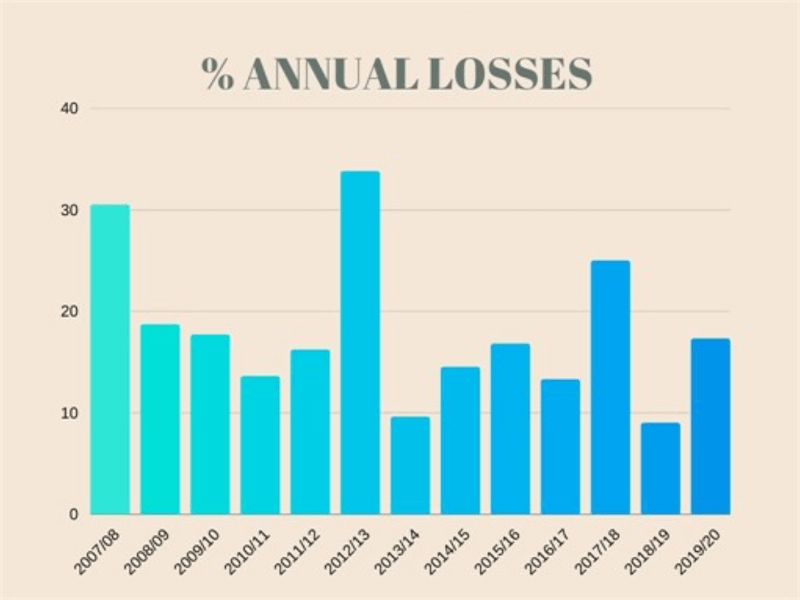

In the UK, losses over the last 12 years have fluctuated between 9% and 34%. This self-selecting survey includes responses from about 10% of the British Beekeepers Association membership (primarily England and Wales, despite the name). The average number of hives maintained by a BBKA member is about 5, meaning – all other things being equal {{1}} – that most beekeepers should expect to lose about 1 hive every winter.

About 30 countries, mainly Northern hemisphere, contribute to the COLOSS survey which is significantly larger scale. The most recent {{2}} data published (for the ’16/’17 winter) had data from ~15,000 respondents {{3}} managing over 400,000 hives. Of these, ~21% were lost for a variety of reasons. COLOSS data is presented as an unwieldy table, rather than graphically. Further details, including recently published results, are linked from their website.

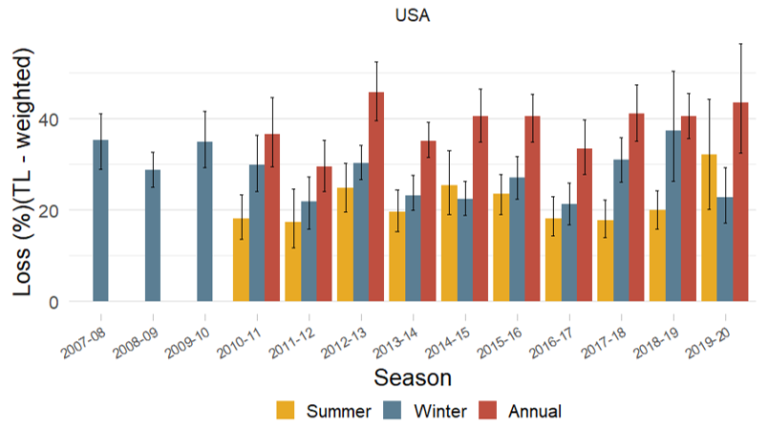

In the USA the Bee Informed Partnership surveys losses – both winter and summer – and claims to have results that cover ~10% of all the colonies in the country (so probably between 250,000 and 275,000 hives ... note BIP appear to be defunct, so I've removed the link). Winter losses in the USA are rarely reported at less than 20% and were as high as 35% in the ’18/’19 winter {{4}}.

Are these figures to be trusted?

Who knows?

Each survey is accompanied by a variety of statistics. However, since they all appear to be based upon voluntary reporting by a subset of beekeepers, there are opportunities for all sorts of data to be included (and even more to be missed entirely).

The problem with surveys

Is the successful beekeeper who managed to get all her colonies through the winter more likely to respond?

A form of ‘bragging rights’.

What about the beekeeper that lost all his colonies?

Does he respond out of a sense of responsibility?

Or does he keep quiet because he doesn’t want to be reminded of those cold, quiet, mouldy boxes opened on the first warm day of spring?

One and two year beekeepers

What about the high level of annual ‘churn’ amongst beekeepers? They buy a nuc in May, filled with enthusiasm about the jars of golden honey they’ll have for family and friends in late summer.

To say nothing of all the “saving the bees” they’ll be doing.

But by late summer the colony is queenless and has an unpleasant temperament.

Psychopathic you might say … if you were feeling uncharitable.

Consequently the Varroa treatment goes on far too late,. Or is quietly forgotten. The winter bees have high viral loads and ‘die like flies’ {{5}}, resulting in the colony succumbing by the year end.

But this colony loss is never recorded on any surveys.

The once enthusiastic beekeeper has moved on and is now passionate about growing prize-winning vegetables or cheesemaking or keeping chickens.

Beekeeping associations train lots of new beekeepers and – although membership numbers are increasing – it’s well below the rate they’re trained at.

Some may not be ‘joiners’ and go their own way.

Many just quietly stop after a year or two.

How many people have you met that say “Oh yes, I used to keep bees”?

Did you ask them whether they ever completed a winter losses survey?

I’m not sure any of the surveys listed above do much ‘groundtruthing’ to establish whether the data they collect is truly representative of the population actually surveyed. With large numbers of respondents spread across a wide geographic and climatic range it’s not an easy thing to do.

So, treat these surveys with a healthy degree of scepticism.

Undoubtedly there are high levels of winter losses – at least sometimes – and the overall level of losses varies from year to year.

Losses and costs

The direct financial cost of these colony losses to beekeepers is very high.

Ignoring time invested and ‘consumables’ like food, miticides and foundation these costs in ’16/’17 for just Austria, the Czech Republic and Macedonia were estimated at €56 million 😯

These figures simply reflect lost honey production and the value of the lost colonies. They do not include the indirect costs resulting from lost pollination.

But, for the small scale beekeeper, these economic losses are irrelevant.

Most of these beekeepers do not rely on bees for their income.

The real cost is emotional 🙁

It still saddens me when I lose a colony, particularly when I think that the loss was avoidable or due to my incompetence, carelessness or stupidity {{6}}.

Your hives should be quiet in winter, but it hurts when they are silent in spring.

Anatomy of a death

The COLOSS surveys give a breakdown of winter losses in three categories:

- natural disasters

- queen problems

- dead colonies

Natural disasters are things like bears, honey badgers, flooding or falling trees.

We can probably safely ignore honey badgers in the UK, but climate change is increasing the weather extremes that causes flooding and falling trees.

Don’t assume that poly hives are the answer to potential flooding.

They do float, though not necessarily the right way up 🙁

Queen problems cover a variety of issues ranging from reduced fecundity to poor mating (and consequent drone laying) to very early or late – and failed – supersedure {{7}}.

Beekeepers with a lot more experience than me report that queen problems are increasing.

Perhaps the issues with fecundity and drone laying are related to toxic levels of miticides in commercial foundation? It’s certainly known that these residues reduce drone sperm fertility significantly. I intend to return to this topic sometime during the approaching winter … perhaps in time to encourage the use of some foundationless frames for (fertile) drone production 😉

In the ’16/’17 COLOSS data, natural disasters accounted for 1.6% of all overwintered colonies (so ~7.5% of losses), queen problems resulted in the loss of 5.1% of colonies (i.e. ~24% of losses) and the remainder (14.1% of colonies, ~68% of losses) just died.

Just died?

We’ll return to natural disasters (but not bears or honey badgers) and queen problems shortly. What about the majority of losses in which the colony ‘just died’?

If you discuss colony post-mortems with beekeepers they sometimes divide the ‘just died’ category (i.e. those not readily attributable to failed queens, marauding grizzlies or tsunamis) into four groups:

- disease

- isolation starvation

- starvation

- don’t know

The most important disease associated with overwintering colony losses is high levels of Deformed wing virus (DWV). This results from uncontrolled or inadequately controlled Varroa infestation. For any new readers of this site, please refer back to many of the articles I’ve already written on Varroa management {{8}}.

I strongly suspect that a significant proportion of the reported isolation starvation is actually also due to disease, rather than isolation per se.

A consequence of high levels of DWV is that winter bees die prematurely. Consequently, the colony shrinks faster than it would otherwise do. It starts the size of a basketball but (too) rapidly ends up the size of a grapefruit … or an orange.

The small cluster is then unable to remain in contact with stores, and so starves.

Yes, the colony died from ‘isolation starvation’, but the cause was the high levels of Varroa and the viruses it transmits.

What about regular starvation?

Not because the cluster became isolated from the stores, but simply because they had insufficient stores to get through the winter.

Whose fault was that?

And the last category, the “don’t knows”?

I bet most of these are due to high levels of Varroa and DWV as well 🙁

Yes, there will be other reasons … but probably not a huge number.

What’s more … if you don’t know the reason for the colony loss there’s very little you can do to mitigate against it in future seasons.

And, other than wild and increasingly vague speculation, there’s little I can write about if the reason for the loss remains unknown {{9}}.

Avoiding winter losses

So, let’s rationalise those earlier lists into the probable (known) major causes of overwintering colony losses:

- natural disasters

- queen problems

- starvation

- disease (but probably mainly DWV and Varroa)

As the long, hot days of summer gradually shorten and cool as early autumn approaches, you should be thinking about each of these potential causes of overwintering colony loss … and doing what you can to ensure it doesn’t happen to you (or, more correctly, your bees).

Some are easier to deal with than others.

Here’s a whistle-stop tour of some more specific problems and some practical solutions {{10}}. Some, all or none may apply to your bees – it depends upon your location, your climate, your experience and future plans as a beekeeper.

Natural disasters

These fall into two broad groups:

- things you can do almost nothing about (but might be able to avoid)

- things you can relatively easily solve

Flooding, falling trees, lightning, landslides, earthquakes, volcanoes, meteor strikes etc. all fall into the first group.

If you can avoid them, do.

Your local council will have information on areas at risk from flooding. There are also searchable maps available from SEPA. Do not underestimate the severity of some of the recent flooding. Some parts of Scotland and Northern England had 600 mm of rain in two days in 2015.

You might be surprised (and from an insurance aspect, devastated) at the classification of some areas now ‘at risk’.

Consider moving hives to higher ground before the winter rains start. One consequence of climate change is that heavy rainfall is now ~20% heavier than it was a few decades ago. This means that floods occur more frequently, are more extensive and the water levels rise faster. You might not have a chance to move the hives if flooding does occur,

More rain and stronger winds (particularly before leaf fall) mean more trees will come down. You might be able to identify trees potentially at risk from falling. It makes sense to remove them (or site your hives elsewhere).

Lightning, earthquakes, volcanoes, meteor strikes … all a possibility though I would {{11}} probably worry about Varroa and woodpeckers first 😉

Solvable natural disasters

The ‘solvable’ natural disasters include preventing your colonies being robbed by other bees or wasps. Or ransacked by mice or woodpeckers after the first hard frosts start. A solution to many of these are ‘reduced size entrances’ which either enable the colony to better defend itself, or physically restricts access to critters.

The L-shaped ‘kewl floors‘ I use prevent mice from accessing the brood box. They are also easier for the colony to defend from bees/wasps, but can also easily be reduced in size with a narrow piece of hardwood. If you don’t use these types of floor you should probably use a mouseguard.

Woodpeckers {{12}} need to cling onto the outside of the hive to hammer their way through the side. You can either place a wire mesh cage around the hive, or wrap the box in something like damp proof membrane (or polythene) to prevent them gaining purchase on the side walls.

Doing both is probably overkill though 😉

Strong colonies

Before we move onto queen problems – though it is related – it’s worth emphasising that an even better solution to prevent robbing by bees or wasps is to maintain really strong colonies.

Strong colonies with a well balanced population of bees can almost always defend themselves successfully against wasps and robbing bees.

Nucs, that are both weaker and – at least shortly after being made up – unbalanced, are far less able to defend themselves and need some sort of access restriction.

By ‘balanced’ I mean that the numbers and proportions of bees fulfilling the various roles in the nucleus colony are reflective of a full hive e.g. nurse bees, foragers, guard bees.

But the benefits of strong colonies are far greater than just being able to prevent wasps or robbing bees. There is compelling scientific evidence that strong colonies overwinter better.

I don’t mean strong summer colonies, I mean colonies that are strong in the late autumn when they are fully populated with the winter bees.

Almost the entire complement of bees in the hive are replaced between late summer and late autumn. Remember that a really strong summer colony may not be strong in the winter if Varroa and virus levels have not been controlled.

How do you ensure your colonies are strong?

- Minimise disease by controlling Varroa levels in early autumn to guarantee the all-important winter bees are reared without being exposed to high levels of DWV.

- Try and use a miticide treatment that does not reduce the laying rate of the queen.

- Avoid blocking the brood nest with stores where the queen should be laying eggs.

- Requeen your colonies regularly. Young queens lay more eggs later into the autumn. As a consequence the colonies have increased populations of winter bees.

- Unite weak colonies (assuming they are disease-free) with stronger colonies. The former may well not survive anyway, and the latter will have a better chance of surviving if it is even stronger – see below.

- Use local bees. There’s good evidence that local bees (i.e. reared locally, not imported from elsewhere) overwinter better, not least because they produce stronger colonies.

Uniting – take your losses in the autumn

My regular colony inspections every 7-10 days during May and June are pretty much abandoned by July. The risk of swarming is very much reduced after the ‘June gap’ in my experience.

I still check the colonies periodically and I’m usually still rearing queens. However, the rigour with which I check for queen cells is much reduced. By July my colonies are usually committed to single-mindedly filling the supers with summer nectar.

They are already making their own preparations for the long winter ahead.

Although the inspections are less rigorous, I do keep a careful watch on the strength of each colony. Often this is directly related to the number of supers I’ve had to pile on top.

Colonies that are underperforming, and – more specifically – understrength are almost always united with a stronger colony.

Experience has taught me that an understrength colony is usually more trouble than it’s worth. If it’s disease-free it may well overwinter reasonably well. However, it’s likely to start brood rearing more slowly and build up less well. It may also need more mollycoddling {{13}} in the autumn e.g. protection from wasps or robbing bees.

However, a colony that is not flourishing in the summer is much more likely to struggle and fail during the winter. Perhaps the queen is not quite ‘firing on all cylinders’ and laying at a really good rate, or she might be poorly mated.

Far better that the workforce contributes to strengthening another hive, rather than collect an underwhelming amount of honey before entering the winter and eventually becoming a statistic.

My winter losses are low and, over the last decade, reducing.

That’s partly because my Varroa management is reasonably thorough.

However, it’s probably mainly due to ensuring only strong colonies go into the winter in the first place.

Newspaper

I’ve dealt with uniting in several previous posts.

It’s a two minute job.

You remove the queen from the weak colony, stack one brood box over the other separated by a sheet or two of newspaper with a very small (~3mm) hole in the middle. Add the roof and leave them to get on with things.

I don’t think it makes any difference whether the strong colony goes on the top or the bottom.

I place the colony I’m moving above the box I’m uniting it with. My – wildly unscientific – rationale being that the bees in the top box will have to negotiate the route to the hive entrance and, in doing so, will help them orientate to the new location faster {{14}}.

If you unite colonies early or late in the day most foragers will be ‘at home’ so not too many bees will return to find their hive missing.

If there are supers on one or both hives you can separate them with newspaper as well. Alternatively, use a clearer the day before to empty the supers prior to uniting the colonies. You can then add back the supers you want and redistribute the remainder to other hives in the apiary.

Don’t be in too much of a hurry to check for successful uniting.

Leave them a week. The last thing you want is for the queen to get killed in an unseemly melee caused by you disturbing them before they have properly settled.

Done properly, uniting is almost foolproof. I reckon over 95% of colonies I unite are successful.

That’s all folks … more on ‘Cutting your losses’ next week 🙂

Notes

At just over 3000 words this post got a bit out of control … I’ll deal with more significant queen problems, feeding colonies, the weather and some miscellaneous ‘odds and sods’ next week.

{{1}}: Which they’re not

{{2}}: At least that I could find.

{{3}}: Actually, far more than this but they do a lot of ‘sanity checking’ on the submissions and chuck out those that are nonsensical e.g. those from people ending the winter with more hives than they started.

{{4}}: Note that the total annual losses are not simply the addition of the summer and winter figures.

{{5}}: If you’ll excuse the entomological misclassification.

{{6}}: I have an abundance of all three.

{{7}}: Perhaps that should be attempted supersedure?

{{8}}: Regular readers are probably sick and tired of the subject. I make no apologies for this as it’s probably the most important part of good beekeeping practice.

{{9}}: Not that that’s ever stopped me in the past.

{{10}}: I’ll deal with feeding colonies, the weather and a few other miscellaneous things next week.

{{11}}: And that’s even though I live quite close to the Ardnamurchan Ring Complex, an ancient volcano (but not active for about 60 million years).

{{12}}: Interestingly it’s only some green woodpeckers that cause problems. It’s a learned activity and many have yet to learn how to do it.

{{13}}: Interesting etymology … moll meaning a girl or prostitute, and ‘coddle’ derived from caldus/m, the Latin for warm/warm drink via caudle (administer invalid’s gruel) to coddle in the mid-16th Century meaning to gently boil fruit.

{{14}}: Though I’ve done it – deliberately or by accident – using every possible permutation of box and location.

Join the discussion ...