A June Gap

As far as the beekeeping season is concerned, we’ve had the starter and we’re now waiting for the main course.

Like restaurants, the size of the ‘starter’ depends upon your location. If you live in an area with lots of oil seed rape (OSR) and other early nectar, the spring honey crop might account for the majority of your annual honey.

If you are in the west, or take your hives to the hills, you might have skipped the starter altogether hoping the heather is the all-you-can-eat buffet of the season.

Lockdown honey

In Fife they appear to be growing less OSR as the farmers have had problems with flea beetle since the neonicotinoid ban was introduced.

Nevertheless, my bees are in range of a couple of fields and – if the weather behaves – usually get a reasonable crop from it. My earlier plans to move hives directly onto the fields, saving the bees a few hundred yards of flying to and fro, was thwarted (like so much else this year) by the pandemic.

The timing of the spring honey harvest is variable, and quite important. You want it to be late enough that the bees have collected what they can and had a chance to ripen it properly so that the water content is below 20% {{1}}.

However, you can’t leave it too late. Fast-granulating OSR honey sets hard in the frames and then cannot be extracted without melting. In addition, there’s often a dearth of nectar in the weeks after the OSR finishes and the bees can end up eating their stores, leaving the beekeeper with nothing 🙁

Judging all that from 150 miles away on the west coast where I’m currently based was a bit tricky. I had to timetable a return visit to also check on queen mating and the build up of all the colonies I’d used the nucleus method of swarm control on.

Ideally all in the same visit.

Blowin’ in the wind

I’d made up the nucs, added supers and last checked my colonies around the 17-19th of May. I finally returned on the 10th of June.

In the intervening period I’d been worried about one of my more exposed apiaries. I’d run out of ratchet straps to hold the hives together and was aware there had been some gales in late May.

Sure enough, when I got to the apiary, there was ample evidence of the gales …

The only unsecured hive was completely untouched and the bees were happily working away. However, one of the strapped hives had been toppled and was laying face (i.e. entrance) down. You can see the dent in the fence where it collided on its descent.

If she hadn’t already (and I expect she hadn’t based upon the date of the gales) I suspect the queen struggled to get out and mate from this hive 🙁

Two adjacent 8-frame nucs were also sitting lidless in the gentle rain. The lids and the large piece of timber they’d been held down with were on the ground. The perspex crownboards were shattered into dozens of pieces.

These bees were fine.

Both queens were laying and the bees were using the new top entrance (!) for entering and leaving the hive. They were a little subdued and the colonies were less well developed than the other nucs (see below). However, their survival for the best part of three weeks uncovered is a tribute to their resilience.

They were thoroughly confused how to get back into the hive after I replaced the lids 🙂

Slow queen mating

Other than extracting, the primary purpose of this visit was to check the queenright nucs from my swarm control weren’t running out of space, and to check on the progress of queen mating in the original colonies.

Queen mating always takes longer than you expect.

Or than I expect at least.

Poor weather hampered my inspection of all re-queening colonies but, of those I looked at, 50% had new laying queens and the others looked as though they would very soon.

By which I mean the colonies were calm and ‘behaved’ queenright, they were foraging well and the centre of the ‘broodnest’ (or what would be the centre if there was any brood) was being kept clear of nectar and had large patches of polished cells.

Overall it was a bit too soon to be sure everything was OK, but I expect it is.

However, it wasn’t too soon to check the nucs.

Overflowing nucs

In fact, it was almost too late …

With one exception the nucs were near to overflowing with bees and brood.

I favour the Thorne’s Everynuc which has an integral feeder at one end of the box. Once the bees start drawing comb in the feeder they’re running desperately short of space.

Most had started …

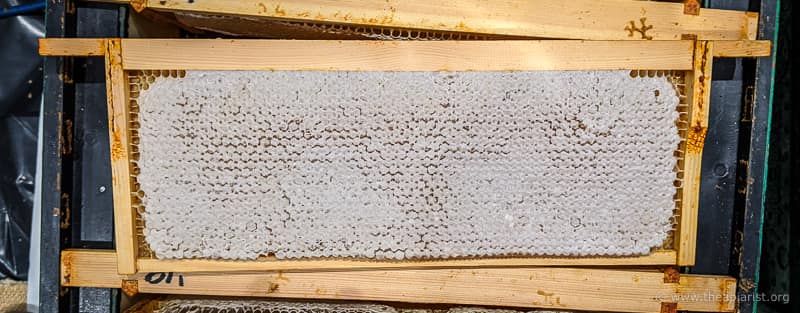

I didn’t photograph any of the nucs, but the photo above (of an overly-full overwintered nuc) shows what I mean; the feeder is on the right.

The nucs had been made up with one frame of predominantly emerging brood, a few more nurse bees, two foundationless frames, a frame of drawn comb and a frame of stores.

They were now all packed with 5 frames of brood and would have started making swarm preparations within a few days if I hadn’t dealt with them.

And the queens had laid beautiful solid sheets of brood (always reasonably easy if the comb is brand new).

Housekeeping and more swarm prevention

The beauty of the nucleus method of swarm control is that you have the older queen ‘in reserve’ should the new queen not get mated, or be of poor quality.

The problem I was faced with was that the new queens weren’t all yet laying (and for those that were it was too soon to determine their quality), but the older queen was in a box they were rapidly outgrowing.

I therefore removed at least three frames of brood {{2}} from each nuc and used it to boost the re-queening colonies, replacing the brood-filled frames with fresh foundation {{3}}.

The nucs will build up again strongly and the full colonies will benefit from a brood boost to make up for some of the bees lost during requeening. Some of the transferred frames had open brood. These produce pheromones that should hold back the development of laying workers.

Finally, if the requeening colonies actually lack a queen (the weather was poor and I didn’t search very hard in any of them) there should be a few larvae young enough on the transferred frames for them to draw a new queen cell if needed.

I marked the introduced frames so I can check them quickly on my next visit to the apiary.

This frame needs to be replaced … but could be used in a bait hive next year

The additional benefit of moving brood from the nucs to the full colonies is that it gave me an opportunity to remove some old, dark frames from the latter.

Shown above is one of the removed frames. As the colony is broodless {{4}} and there’s the usual reduction in available nectar in early/mid June, many of the frames in the brood box were largely empty and can easily be replaced with better quality comb.

Everyone’s a winner 😉

Drone laying queen

One of the nucs made in mid/late May had failed. The queen had developed into a drone layer.

The laying pattern was focused around the middle of frame indicating it had been laid by a queen. If it had been laying workers the drone brood would be scattered all over the frames.

There was no reasonable or efficient way to save this colony. The queen was removed and I then shook the bees out in front of a row of strong hives.

I was surprised I’d not seen problems with this queen when making up the nucs in May {{5}}. I do know that all the colonies had worker brood because the nucs were all made containing one frame of emerging (worker) brood.

Perhaps the shock of being dumped into a new box stopped her laying fertilised eggs. Probably it was just a coincidence. We’ll ever know …

Extraction

And, in between righting toppled hives, checking for queens, stopping nucs from swarming, moving a dozen hives/nucs, boosting requeening hives and replacing comb … I extracted a very good crop of spring honey.

Although I had fewer ‘production’ hives this season than previous years (to reduce my workload during the lockdown) I still managed to get a more than respectable spring harvest. In fact, it was my best spring since moving back to Scotland in 2015.

The crop wasn’t as large as I’d managed previously in Warwickshire, but the season here starts almost a month later.

I start my supers with 10 or 11 frames, but once they are drawn I reduce to 9 frames. With a good nectar flow the bees draw out the comb very nicely.

The bees use less wax (many of my frames are also drawn on drone foundation, so even less wax than worker comb {{6}}), it’s easier to uncap and I have fewer frames to extract.

Again … everyone’s a winner 😉

Not the June gap

Quite a few frames contained fresh nectar, so there was clearly a flow of something (other than rain, which seemed to predominate during my visit) going on. These frames are easy to identify as they drip nectar over the floor as you lift them out to uncap 🙁

In some years you find frames with a big central capped region – enough to usefully extract – but containing lots of drippy fresh nectar in the uncapped cells at the edges and shoulders. I’ve heard that some beekeepers do a low speed spin in the extractor to remove the nectar, then uncap and extract the ripe honey.

I generally don’t bother and instead just stick these back in the hive.

If there’s one task more tiresome than extracting it’s cleaning the extractor afterwards. To have to also clean the extractor during extracting (to avoid the high water content nectar from spoiling the honey) is asking too much!

Colonies can starve during a prolonged nectar dearth in June. All of mine were left with some stores in the brood box and with the returned wet supers. That, plus the clear evidence for some nectar being collected, means they should be OK.

National Honey monitoring Scheme

I have apiaries in different parts of Fife. The bees therefore forage in distinct areas and have access to a variety of different nectar sources.

It’s sometimes relatively easy to determine what they’ve been collecting nectar from – if the back of the thorax has a white(ish) stripe on it and it’s late summer they’re hammering the balsam, if they’ve got bags of yellow pollen and the bees are yellow and the fields all around are yellow it’s probably rape.

But it might not be.

To be certain you need to analyse the pollen.

The old skool way of doing this is by microscopy. Honey – at least the top quality honey produced by local amateur beekeepers {{7}} – contains lots of pollen. Broadly speaking, the relative proportions of the different pollens – which can usually be distinguished microscopically – tells you the plants the nectar was collected from.

The cutting edge way to achieve the same thing in a fraction of the time (albeit at great expense) is to use so-called next generation sequencing to catalogue all the pollen present in the sample.

Pollen contains nucleic acid and the sequence of the nucleotides in the nucleic acid are uniquely characteristics of particular plant species. You can easily get both qualitative and quantitative data.

And this is exactly what the National Honey Monitoring Scheme is doing.

They use the data “to monitor long-term changes in the condition and health of the countryside” but they provide the beekeeper’s involved with the information of pollen types and proportions in their honey.

Samples must be taken directly from capped comb. It’s a messy business. Fortunately the labelling on the sample bottles is waterproof so everything can be thoroughly rinsed before popping them into the post for future analysis.

I have samples analysed already from last year and will have spring and summer samples from a different apiary this season. I’ll write in the future about what the results look like, together with a more in-depth explanation of the technology used.

When I last checked you could still register to take part and have your own honey analysed.

Notes

Lockdown means there have been more visitors than ever to this site, with numbers up at least 75% over this time last year.

This, coupled with the need to upgrade some of the underlying software that keeps this site together, means I’m in the middle of moving to a bigger, faster, better (more expensive 🙁 ) server. I’m beginning to regret the bloat of wordpress over the lean and mean Hugo or Jekyll-type templating systems (and if this means nothing to you then I’m in good company) and may yet switch.

In the meantime, bear with me … there may be some broken links littering a few pages. If it looks and works really badly, clear your browser cache, re-check things and please send me an email using the link at the bottom of the right hand column.

Thank you

{{1}}: Or there’s a risk it will ferment … aside from the small matter that you can’t sell anything but heather honey if the water content is above 20%.

{{2}}: Just the brood frames, not the adhering bees.

{{3}}: For once, not foundationless … the nucs are on a variety of stands, some of which are far from level. Bees draw comb vertical. If there are flanking frames they maintain the correct beespace, but since I was replacing 3/5ths (and in a couple of cases 4/5ths) this wasn’t possible, so I used up some of my foundation mountain leftover from shifting to predominantly foundationless frames.

{{4}}: Or was until I added some back.

{{5}}: … clearly I hadn’t looked carefully enough.

{{6}}: About 25% less by my calculations.

{{7}}: The same cannot be said of the bulk, blended, commercial, ultra-filtered rubbish sold by the ton at £1/lb in a supermarket near you.

Join the discussion ...