Irrational Varroa control

About a month ago I wrote a post on rational Varroa control. I define this as choosing a miticide appropriate for your colony {{1}} and environment, administering it properly and at the right time so providing the maximum benefit to your bees. The long term goal of rational Varroa control is reduced colony losses due to mite-transmitted viruses.

Primarily this means reduced overwintering losses due to Deformed wing virus.

I regularly give talks on this topic. In these I provide a few brief examples of the misuse of miticides. Some of these examples originate – anonymised – in questions I’ve received in previous talks or by email. Some are from surveys of miticide usage.

A few (a very few) are from direct personal experience 🙁

I’m aware that these examples qualify as ‘misuse’ because I’ve read up about the active ingredient in miticides and have a reasonable understanding of how, when and why they work.

Misuse could probably be broken down into three divisions:

- Incorrect usage that does not reduce the efficacy of the treatment.

- Using the miticide in a manner that significantly reduces its efficacy, but otherwise does little or no harm.

- Incorrect usage that has no impact upon the mite population and/or that significantly harms the colony and/or spoils the honey.

After a short {{2}} preamble, I’ll outline some of the more glaring examples. Keep these in mind when planning your mite control strategy and you should see improved winter survival, better spring build up, stronger summer colonies … and more honey 🙂

What can I use?

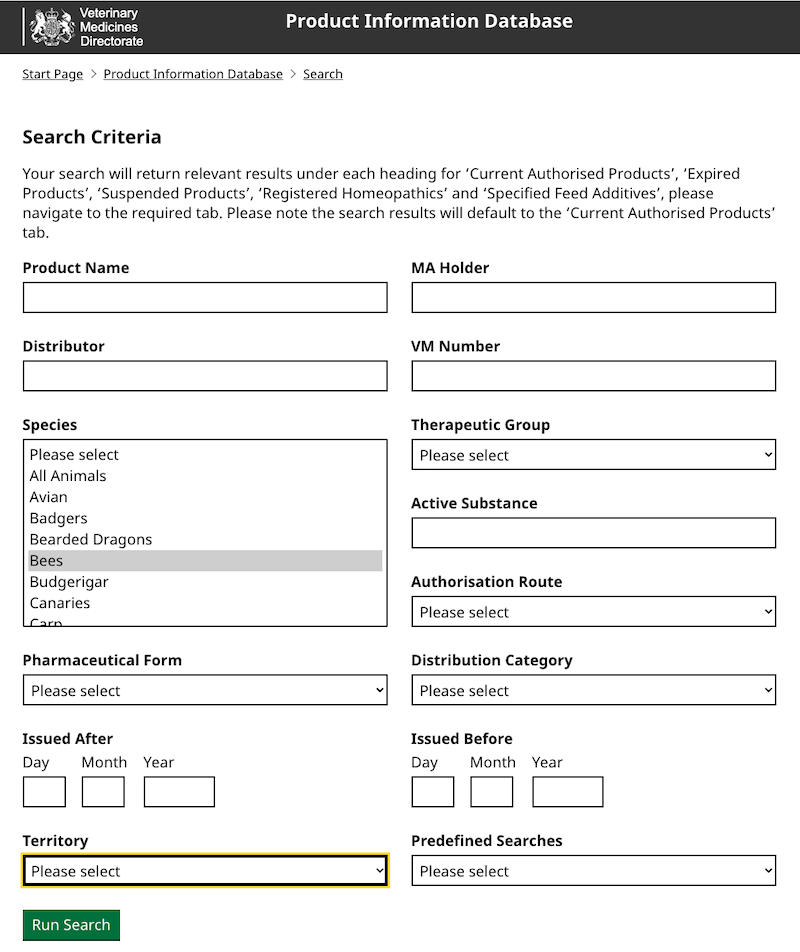

The Veterinary Medicines Directorate maintain a list of miticides approved for use on honey bees (and other animals). It’s a large database and I find the easiest way to see the current product list – which changes quite regularly as things are added and removed – is to use the search facility.

Simply select ‘Bees’ from species list (they’re between ‘Bearded dragons’ and ‘Budgies’!) and then hit the big Run search button at the bottom.

There are currently 31 approved products though this contains a number of duplicates as Great Britain and Northern Ireland are listed as separate territories.

In my view, the two most important useful columns in the returned table are the ‘Active substance‘ and the ‘Aligned product‘.

The active substance is the chemical in the miticide that is responsible for killing mites.

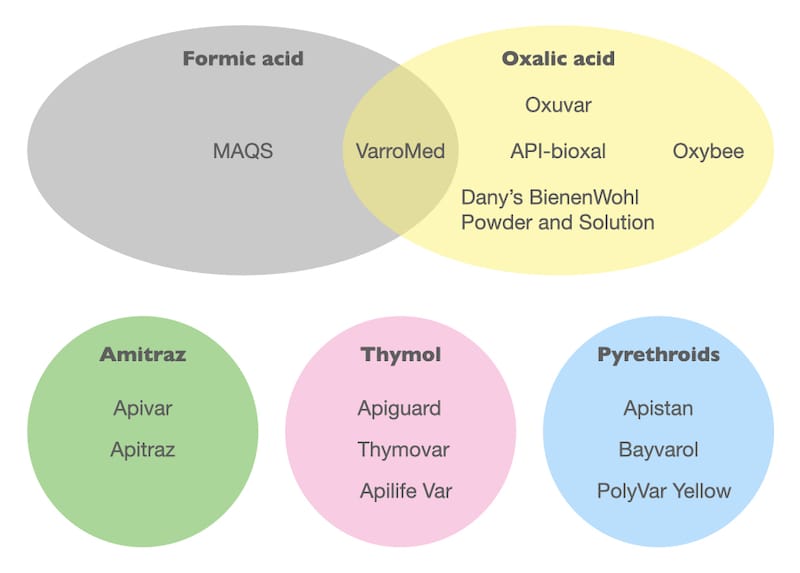

Look down the list. There are relatively few different active substances, present alone or in combination.

I currently count just five.

Thymol, amitraz, pyrethroids, formic acid and oxalic acid.

I’m ignoring the minor components like eucalyptus oil that, individually, do not have high levels of miticidal activity.

Flumethrin and tau-fluvalinate (the active ingredients of Bayvarol and Apistan respectively) are both pyrethroids and have the same mode of action (and, more importantly, resistance to one usually confers resistance to the other).

What about management methods to control mites?

The VMD database lists the miticidal products approved for treating honey bees.

They don’t list management techniques like drone brood uncapping or small cell foundation, or the application of non-toxic compounds like dusting with icing sugar.

There’s nothing to stop you using these approaches.

However, first conduct some sort of cost-benefit analysis to determine if they are worthwhile.

Is the disruption to the colony, or the potential tainting of honey stores, justified by the reduction of Varroa numbers?

For example, Randy Oliver has done some analysis of the impact of sugar dusting and shows that – at best and with weekly applications – it might be able to hold Varroa levels steady. You can download his Excel calculations and play with some of the assumptions.

If you increase the percentage of mites capped in cells from 60% (which is probably rather conservative) and decrease the percentage of mites dislodged by sugar dusting from 40% (which is probably rather aggressive) then mite replication rapidly outruns the control method applied.

That’s a questionable ‘benefit’ in return for the disruption of blowing 120 g of icing sugar into the hive every 7 days {{3}} … but there’s nothing to stop you using it as a control method.

Though it might not do much controlling … 🙁

I choose miticides that kill at least 90% of mites when used properly. I prefer to use miticides once or twice during the season, rather than dabbling every other week or month.

What can’t or shouldn’t I use?

You cannot use things like fenpyroximate, spirotetramat or spirodiclofen.

What?

These are used for mite or tick treatment of other animals or plants {{4}}. They have been shown to be effective against Varroa (though at high levels they may also kill bees) but are not approved for use.

Remember also that VMD approval involves both the compound and the mode by which it is administered.

Amitraz is approved for use as the active ingredient in Apivar strips. However, in Great Britain and Northern Ireland you cannot fumigate colonies with amitraz … which, as Apiwarol, is a popular treatment method in Poland.

There are some (perhaps surprising) ‘restrictions’ in terms of approved usage. Api-Bioxal can be used to trickle treat twice per season, but only used once for vaporisation.

Why?

This is one of the many oddities buried in the depths of the VMD database.

Api-Bioxal is not approved for spray administration, but Oxuvar is. Both have the same active ingredient.

No wonder beekeepers find this confusing … 🙁

Read the instructions and other documentation

Miticides approved by the VMD come with documentation. This takes the form of the instructions written (often in really tiny print) on the packet. The other thing written on the packet is the ‘use by’ date.

Keep the packaging 🙂

Read the instructions for use.

It may seem like an obvious thing to suggest but at least a third of the questions I get asked are answered in the documentation.

Part of the problem is the wording that’s often used or the apparent (and sometimes real) contradictions between the instructions provided for two miticides that have the same active ingredient and formulation {{5}}.

For more legible documentation you could refer again to the VMD database of approved miticides. If you following the ‘Aligned product’ link you will have access to several additional pieces of information, most useful of which are the Summary of product characteristics and the Product literature. The latter is a copy of the literature in a very easy-to-read format, without any fancy colours or tiny fonts.

Keep records

You should keep records of when you treat and what you treat with, including batch numbers. I simply keep the packet the miticide was supplied in. I know when I treated as my copious {{6}} notes record the dates … and allow me to work out when the period of treatment is finished.

Even easier … just take a photograph of the empty packet, but make sure you include the batch number in the shot.

Examples of miticide misuse

It’s not possible to provide a comprehensive set of examples of miticide misuse (or Irrational Varroa control) … at least not in ~2000 words 😉 – after all, there might be one or two ways to use a miticide properly, but thousands of ways it could be used improperly.

Here is a non-exclusive and far-from-comprehensive list of miticide misuse or bad practice.

Don’t do this at home … or in the out apiary 😉

Too little

Use the correct dose. Using less than the recommended dose ensures that some mites will survive. This may lead to the development of mite resistance.

Some beekeepers have been known to add a single strip of Apivar to colonies in preparation for going to the heather moors.

This is bad practice.

Even worse … some have been found leaving the strip in the hive while they were at the heather. Is that forgetfulness or just reckless? The honey will be tainted and the long-term exposure to low levels of amitraz may contribute to the development of resistance {{7}}.

Too late

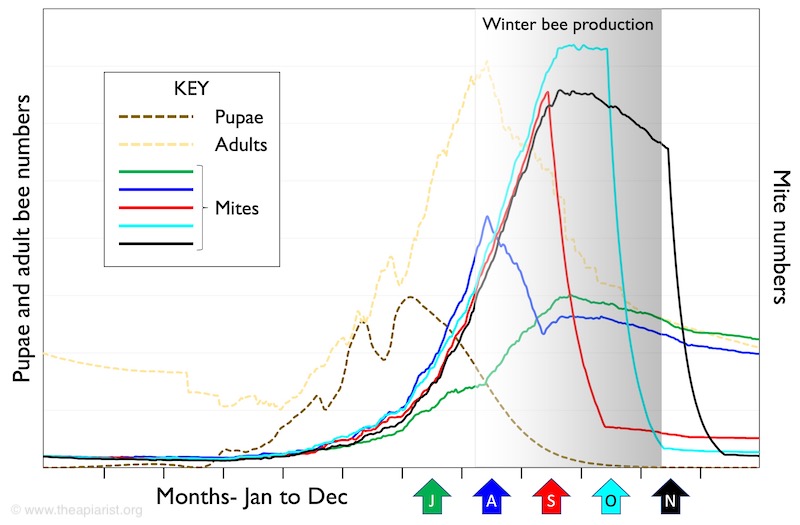

Remember that the goal of the late summer treatment is to prevent the developing winter bees from being exposed to Varroa and the viruses that the mite transmits.

If you treat too late in the season you may well kill lots of mites, but the winter bees will already have been exposed.

In the graph above, treating in mid-October will kill significantly more mites than treating in mid-August.

But that’s not really the goal.

An October treatment will kill more mites because they’ve been breeding like rabbits throughout September.

And, what have they been reproducing on? Your developing winter bee pupae 🙁

Winter bee production is not an all or nothing event. The colony does not switch from producing summer bees to winter bees on a particular date. As late summer segues into early autumn an increasing proportion of the developing brood will be winter bees.

It’s your responsibility to ensure that enough of them are protected from Varroa so that they can lead a long and protective life, getting the colony through until February or March next year.

Too much

Many miticides are reasonably well tolerated by bees. Nevertheless, overdosing is also to be avoided. If you read the product characteristics for Api-Bioxal for example it states that:

Significantly higher bee mortality was observed in hives that received double (by sublimation) or triple (by trickling) dosages of product. In addition, when overdosed, the over-wintering capacity of colonies was diminished and there may be detrimental effects on colony development in the future {{8}}.

Remember that nucleus colonies are smaller than full sized colonies. It’s not unusual for a beekeeper to administer a full dose to what is essentially a half-sized colony.

In the case of Amitraz, ‘overdosing’ is well tolerated and two strips in a nucleus colony is unlikely to do the bees any harm.

However, the same cannot be said of MAQS. The product characteristics for MAQS specifically state that it should not be used for colonies with less than 6 frames of brood.

Too high

The formic acid-containing MAQS is poorly tolerated by the colony at high ambient temperatures. The literature suggests it should not be used when the peak daily temperature might exceed 29.5°C.

I’ve never used MAQS. I’m told by other beekeepers that they’ve had problems with queen losses at temperatures as ‘low’ as 25°C.

Remember, when you add the MAQS strips they need to be in the hive for 7 days. You therefore need to check the forecast for the week ahead before starting treatment.

Too low

Alison Gray and Magnus Peterson (both at Strathclyde University) have conducted surveys of Scottish beekeepers for about the last 15 years, summaries of which appear annually in The Scottish Beekeeper. Results are also collated into the COLOSS analysis.

The surveys have evolved over the years, but have included questions on the type and timing of treatment.

I read some of these carefully when I returned to live in Scotland (in 2015). I was interested to see what other beekeepers were using. One thing that surprised me was the amount and timing of thymol (Apiguard) treatment.

For example, in the 2014 report (PDF), ~25% of treatments used were thymol, with 60% of these being applied in September, October and November.

A quick check of the Apiguard Product characteristics turns up the following statement:

Do not use the product when the maximum daily temperature expected during the treatment is lower than 15°C or when the colony activity is very low or when temperature is above 40°C.

I don’t know anywhere in Scotland in where the maximum daily temperature exceeds 15°C for four weeks (the duration of treatment) between September and November.

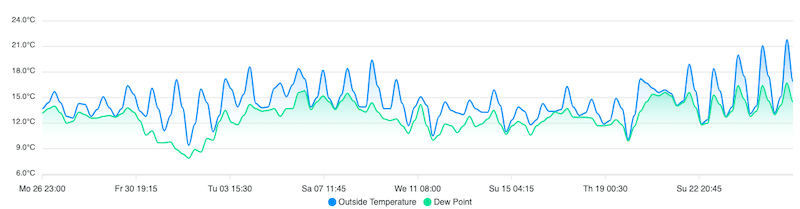

I checked a personal weather station a couple of miles from my apiaries in Fife … in October 2013 the average temperature was 11.5°C, but the maximum failed to reach 15°C on 10 days through the month.

Inevitably, the efficacy of treatment would be reduced.

West coast temperatures 26/7/21 to 26/8/21 … 7 days fail to reach 15°C making Apiguard a very poor choice here.

You need good long range weather forecasting skills. Prior experience of what might be expected can really help your planning in these circumstances.

Too long

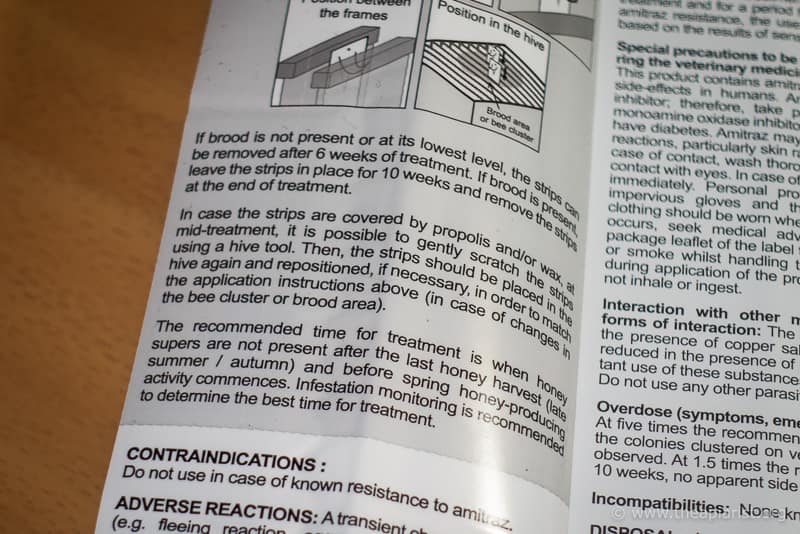

Do not leave Apivar strips in the colony longer than stated in the instructions.

How long is that?

Again, from the Product characteristics documentation:

If brood is not present or at its lowest level, the strips can be removed after 6 weeks of treatment. If brood is present, leave the strips in place for 10 weeks and remove the strips at the end of treatment.

Strips added to a colony with a young queen (and therefore laying well, and late into the year) on the day this article appears {{9}} should probably be removed in the first week of November.

That’s not a great time of year to be lifting roofs and prising up crownboards.

However, the alternative is worse. If you leave the strips in situ you ensure that any surviving mites (and there will be some) are continuously exposed to a low level of amitraz … perfect conditions to help select for resistance 🙁

Too short

This is much the same as too little (see above). If you remove the miticide before the correct period of time has elapsed then some mites will escape treatment.

No miticide is 100% effective. However, why store up problems for the future by unnecessarily reducing the efficacy of the treatment?

Remember … the only good mite is a dead mite.

Too old

Miticides are not inexpensive. It is therefore very tempting to save and re-use opened packets.

For example, beekeepers with just a couple of hives still have to purchase a packet of Apivar {{10}} for an eye-watering £31. It must be very tempting to tuck the unused portion away in the shed for the next time.

And, when they do, how many do a before and after count of phoretic mites to confirm that the treatment worked?

I suspect very few.

If they did they might be in for a bit of a disappointment.

Amitraz, the active ingredient in Apivar strips, is quite unstable and rapidly degrades. I’ve used strips from previously opened packets and observed that they were significantly less effective {{11}}.

What I should have done was read the Product characteristics documentation where it clearly states:

Shelf life after first opening the immediate packaging: use immediately and discard

any unused product.

Similar problems (short or non-existent shelf life) apply to some of the oxalic acid-containing solutions, in this case because they degrade to product hydroxymethylfurfural which is toxic to bees at high concentrations (see the notes on this at the end of the post of preparing Api-Bioxal for trickle treating).

One and two hive owners should coordinate their purchases and treatment of colonies to avoid wasting money.

Coordinated treatment has additional benefits, which neatly takes me to the final topic …

Too few

OK, these titles are getting a bit contrived now, but this is the last one 😉

Treat all the colonies in the apiary simultaneously. I’ve written extensively about drifting and robbing. Both activities redistribute adult bees and the mites piggybacking on them around the apiary (or the wider environment).

If you treat just one colony it will soon {{12}} become reinfested with mites from neighbouring colonies.

If you don’t treat one colony and it develops high mite levels in autumn, perhaps due to a late surge in brood rearing, it will shed mites (hitching a ride on young bees going on orientation flights) to your adjacent treated colonies.

A final note on Apistan and pyrethroid-containing miticides

Resistance to Apistan is widespread. It’s so widespread that the National Bee Unit apparently stopped keeping records a decade or so ago.

Apistan is a very effective miticide … against mites that are sensitive.

If you intend to use Apistan (or any of the approved pyrethroid-containing miticides) I would strongly suggest determining the level of infestation before treatment, and confirming a 90+% reduction in mite levels after treatment.

Unfortunately, just counting the dead mites on the Varroa tray is not evidence that the treatment has been effective.

If you find 1000 dead mites on the tray it just tells you is that you have 1000 mites less in the colony.

There may still be 9000 left if the treatment was only 10% effective …

That’s not going to end well 🙁

{{1}}: Or colonies …

{{2}}: Which, now I’ve written it, appears to be anything but short.

{{3}}: Where does all that sugar go? Some will be undoubtedly eaten, but some may end up – directly or indirectly – in the honey supers.

{{4}}: Though not necessarily in the UK. For example, spirodiclofen is licensed for use against scale insects and mites of fruit trees in many EU countries.

{{5}}: See the comments above on Api-Bioxal and Oxuvar. There is a Scottish Varroa Working Party organised by Luis Molero, the Chief Bee Inspector for Scotland, to try and get rid of some of these contradictions and to provide better advice on mite management for beekeepers.

{{6}}: Oh how we laughed!

{{7}}: So, probably reckless …

{{8}}: Unfortunately, these product characteristics do not give details of how much mortality was observed, or links to the primary data. It’s also worth noting that some of these comments contradict studies on vaporised oxalic acid usage, for example by Thomas Radetzki, Medhat Nasr, Heinz Kaemmerer or Francis Ratnieks.

{{9}}: 27th August 2021.

{{10}}: 10 strips, sufficient for 5 hives.

{{11}}: So ineffective I had to buy some more and retreat … bingo!.

{{12}}: In days – we’ve done this experiment.

Join the discussion ...