False economy

Have you seen the price of nucs this season?

For commercially-supplied overwintered nucs I've seen prices quoted of £260–360, and around £250 for a 2025 5–frame nuc once they're available (which will probably be the middle or end of this month).

Most suppliers appear to have already sold out, suggesting that demand — as ever — is very high early in the season. This demand reflects two things:

- new beekeepers who have recently completed a training course and now wanting (desperately) their first bees, and

- more experienced beekeepers (though perhaps not better beekeepers 😉) who want to make up for winter losses

If you are one of the first group then my advice would be to remain patient.

There should be a glut of nucs available after queen rearing starts in earnest, and certainly by early/mid-June. That's not too late in the season to start with your first bees. You might not get a large summer honey crop, but you will get the opportunity to gain experience as the colony builds up for winter.

Your confidence and abilities will increase as the colony gets bigger, and — with proper winter preparation — you should then be well-placed for the following season.

Good things come to those who wait.

It's never too early to learn that beekeeping is not about instant gratification.

Or, in some seasons, any gratification 😞.

In the meantime, it's swarm season … put out a bait hive or two, attend every apiary training day with your local association, and offer to do all the fetching and carrying for your mentor. You'll gain lots of valuable experience, you'll probably get to see the difference between good and bad bees, and you'll learn something about bee (and beekeeper) behaviour.

All of which will be useful for the months and years ahead.

Bait hives

A week or so here of cooler weather was followed by a stunning warm, sunny day. I noticed a few bees sniffing around the stacks of spare broods and supers I've got piled up (everywhere, I'm told!). The boxes are either empty or — in the case of those containing frames of capped stores for making up nucs later this month — securely sealed.

'Beetight' … though the whole area probably smells wonderful to passing foragers.

Although it's difficult to tell the difference between a few inquisitive bees and initial scout bee activity I set out a bait hive this morning.

By 1 pm there were a hundred or more bees milling around the entrance, flying over, under and around the sides of the hive, and bouncing around inside the box.

If you listen carefully, particularly if it's a poly hive, you can hear them.

These bees are measuring the volume of the void, probably by using a mathematical method termed the 'mean free path length'. This is why it's important to not use frames with foundation when assembling a bait hive; either use foundationless frames, or just one old, dark, frame of comb pushed hard up against the sidewall of the hive (you can always add more frames once a swarm arrives).

The bait hive remained busy until late afternoon when the sun had moved round so far that the entrance was in the shade … I expect they'll be back tomorrow {{1}} and, with good weather predicted for the week ahead, I'm quietly confident a swarm will arrive.

But, as regular readers will be unsurprised to hear, I'm drifting off-topic …

Waning enthusiasms

Those crazy nuc prices need to be added to the — already high — cost of starting beekeeping. There seems to be a never-ending list of 'essential' equipment, in addition to the hive, the beesuit and the bees. I've got a part-written post on this for the future, so won't elaborate further here, other than to say it can rapidly exceed £1000 (and may be much more).

Bait hives are one way to keep those costs down, but the other is to ensure that as many of your colonies survive the winter as possible.

After the relatively long winters we 'enjoy' it's not surprising that there's a huge surge in beekeeping interest and activity once the season starts to warm up. May and June can be manically busy, with spring honey, swarm control, queen rearing and making up all those frames you failed to build in the winter.

Things then calm down a little, the urge to swarm is over (either satisfied by the bees or controlled by the beekeeper), and — for some — the novelty and enthusiasm may start to wane a little. There's the summer honey to look forward to, but then things start to really wind down, until everything is over for the (all too short) season.

But, in some regards, those last few weeks of the season — say from early/mid-August to the end of September {{2}} — are the most important of the year.

Effort invested then, in feeding and Varroa management, is both timely and essential preparation for the following season.

If you get these things right, you won't have to consider spending £250 on replacement nucleus colonies to make up for your winter losses.

But some seasons start and end badly. We cannot control the weather, but we can still manage the health of our colonies.

Why not become a sponsor of The Apiarist?

Sponsorship costs about the same as a large double-shot cappuccino a month and supports my research and weekly writing. Sponsors receive sponsor-only articles to guarantee bee-related reading every week.

Go on, you know it makes sense 😉.

A poor season

Imagine the situation … two of your three colonies died overwinter, and the survivor isn't strong. The colonies were strong in late August, but a check after some hard frosts in late February showed that two were moribund.

Your post-mortem diagnosis was 'isolation starvation', as there were a couple of hundred bees with their heads buried in cells, clustered tightly in the middle of central frames, with ample capped stores on the outer brood frames. The queen, curled into a foetal position, was amongst the corpses.

A pathetic sight.

Your diagnosis was probably wrong.

Yes, the bees starved, but they starved because the colony had shrunk to just a 'couple of hundred bees', probably due to the ravages of viruses transmitted by Varroa. Had the colony been strong, they would have been rearing brood, and the cluster would have occupied sufficient space to 'reach' those outermost stores during the cold weather.

Deflated, but not undeterred, you mollycoddle the surviving colony and search for a source of replacement nucs. £330 is not an option, not least because they were all sold months ago, but you do manage to buy one in June from a local beekeeper (at a much more reasonable price {{3}}) and attract a swarm later that month.

Things are looking up.

However, your mollycoddled colony is only now moderately strong, so is unlikely to generate much excess honey during the summer flow.

As for the purchased nuc or the swarm well, we'll never know, because the summer is a shocker. Cool, wet and windy. Strong colonies generated little honey, and moderate or weak ones, none at all.

Adding injury to insult

So now you're thoroughly deflated.

You've got no honey, three mediocre colonies, and — although it's still warm(ish) — the enforced winter break from beekeeping is approaching fast.

You need to feed the colonies and apply miticides before it's too late in the year.

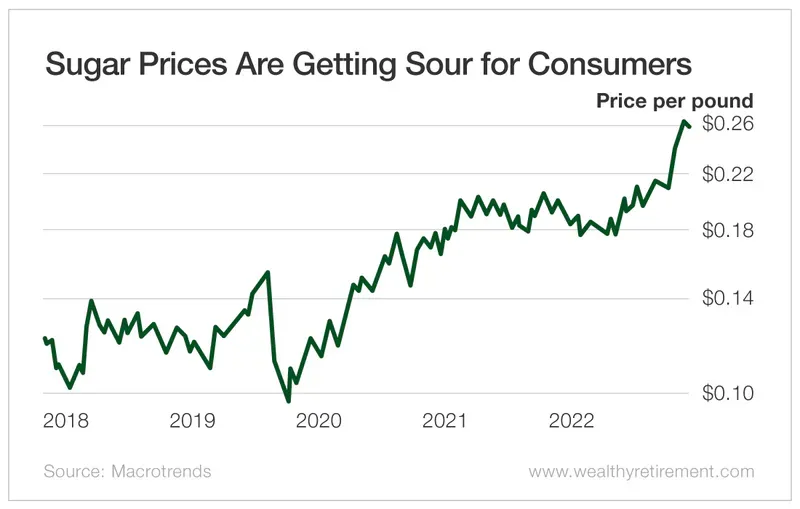

Sugar prices have been creeping up year upon year, and that's before the beekeeping suppliers apply the 'beekeeping-specific' (i.e. eye-watering) surcharges for similar products in different packaging 😉.

And then there is the cost of the miticides.

Yikes!

There are two problems here.

The first is cost and the second is scale.

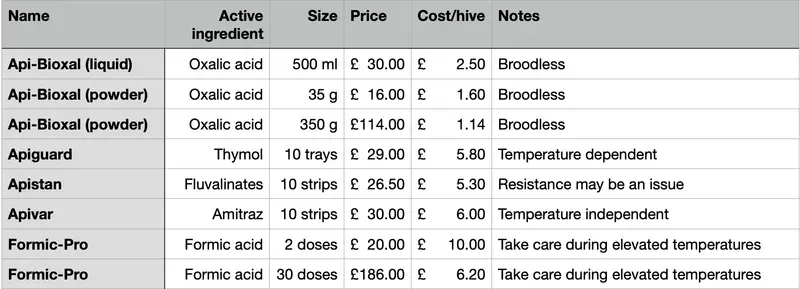

None of the approved miticides are inexpensive (see the table below), and most are supplied in amounts that actively encourage wastage.

You dilly-dally. Should you buy X, and take the hit, or Y which is more but has a much longer shelf-life?

August segues into September. The poor weather continues but at least the colonies won't starve as you have started feeding them. It's now too cold to use the thymol-containing miticides, and you're not keen on the synthetic pyrethroids (wax solubility of residues etc).

Another week of wind and rain, you finally receive your order for the miticides and then wait for a half-decent day to add them to the colony. It's now the last week in September.

The (perceived) insult was the price of the miticides.

The injury is the damage caused to the colony in the intervening period.

With poor weather there will be little foraging, so only limited amounts of pollen will be collected. As pollen intake by the colony dwindles, the bees start producing the winter bees that are long-lived and will get the colony through to the following spring.

But in the absence of miticides, most of these winter bees will be reared in the presence of high levels of mites. Consequently, many of the winter bees will have high amounts of deformed wing virus, either dying during development, or soon afterwards, or expiring prematurely and unnoticed in the cold and quiet of the winter hive.

History is about to be repeated 😞.

The price of miticides

There's a remarkable (or not!) similarity in the price of many approved miticide treatments in the UK. I've not done an exhaustive search for best prices, or included the cost of P&P, or considered every variant of each active ingredient, but here are some representative prices for mid-May 2025.

In each case I've calculated a price per hive assuming you have the appropriate number of hives for the quantity you buy (I'll return to this point later).

The choice of treatment is important but will depend upon a variety of things, most important of which are the state of your colonies (with or without brood), the temperature, and the period you have in which treatment needs to be completed.

Not all of these things will apply to all users, and some may apply to none.

I've written about each of the treatments in other posts (follow the links), but as a quick aide-mémoire here are my thoughts on the most important considerations:

- Api-Bioxal; the colony must be broodless

- Formic-Pro; treatment takes 1 week, poorly tolerated by colonies at elevated temperatures and may result in the loss of the queen

- Apivar; temperature independent, treatment duration 6–10 weeks

- Apistan; temperature independent, Varroa resistance widespread so post-treatment monitoring of treatment efficacy is required

- Apiguard; temperature dependent, efficacy drops rapidly at lower (<15 °C) temperatures

If used correctly, the choice of treatment is not influenced by is considerations of efficacy.

All the treatments listed above will kill 90–95% of the mites in a colony if used according to the instructions.

You pays your money and you takes your choice.

Ouch, that hurts

When I leave Thorne's of Scotland clutching five shiny foil packets of Apivar I'm £150 poorer, and don't have very much to show for my outlay.

Amitraz has been an active ingredient for mite and tick treatments for decades, and the cost of the chemical in the strips must be no more than a few pennies. Add to that the slow-release impregnated strips, the vacuum foil packaging and the labelling, and it still feels like a lot of money for very little.

I know there are other costs — profit, licensing, more profit, advertising, R&D, and not forgetting the profit — but miticides still feel expensive.

And, it's even worse in the case of the oxalic acid-containing treatments like Api-Bioxal. Beekeepers with reasonable memories will remember purchasing 500 g tubs of oxalic acid for £10 … enough to treat about 200 colonies, or at least 'clean the hive' as that was what it was sometimes sold for by the beekeeping suppliers.

But oxalic acid was then commercialised, mixed with glucose, licensed and sold as Api-Bioxal. This, and one or two other formulations (Oxuvar for example), are now the only oxalic acid-containing chemicals you are allowed to use to control mites.

More recently still, oxalic acid has been added to the explosives precursor and poisons (EPP) list, making its purchase effectively impossible for individuals. Don't even try unless you've got a) an EPP licence, photo ID, all of which needs to be validated by the supplier before purchase, or b) you own a business (which doesn't need an EPP licence) that needs to use oxalic acid as part of its business activity … which, obviously, excludes beekeeping as unadulterated oxalic acid is no longer an approved treatment (and, actually, never was 🤦).

Think of it as insurance

There's a big difference between £1.60/hive for Api-Bioxal and the £0.05/hive oxalic acid used to cost {{4}}.

But, that's the wrong way to think about things.

Instead, consider the value of the colony you're applying the miticide to. That value can be defined in terms of the cost to replace it together with the returns you are able to get for the hive products, such as bees, wax, propolis, and honey.

The value of the latter depends upon all sorts of things, and I'm not going to attempt to put a number on it, other than to say it can be 'considerable' (e.g. in a good season a single strong colony should be able to produce ~40 kg of honey and a spare nucleus colony, and more — of both — is possible).

Remembering also that those 'returns' may not be monetary.

Gifting a few jars of honey, or providing a beginner (with poor swarm control and a broodless colony) a frame or two of eggs/larvae or a 'spare' nuc, creates a lot of goodwill.

None of the above can be achieved if your colonies do not get through the winter.

And, if they don't, you'll need to invest in more bees next year to have any hope of achieving those 'considerable' returns.

Therefore, for most beekeepers, a carefully chosen and correctly applied, approved miticide is very worthwhile insurance against winter colony losses.

£5–10/hive/annum sounds like a small price to pay considering the replacement costs and potentially lost returns from non-existent colonies.

A jar of honey

My 'back of an envelope' calculations over the last decade or so indicate that my miticide costs per hive per annum have remained about the same as I sell a single 340 g jar of honey for.

As the price of miticides has increased, so has the price of honey.

It's not exactly the same, and it will vary by area, but it's a reasonable approximation.

So, it still smarts when I pay £150 for chemicals that cost next-to-nothing, and for which the R&D and licensing costs were recouped decades ago. But, in the overall scheme of things, it's a very small price to pay to help protect the health of my colonies.

I don't know if beekeepers really stint on miticide purchases because of the costs, but I do know that:

- some beekeepers have 'short arm and deep pocket' syndrome and resent having to pay for anything (particularly when it used to cost pennies)

- lots of beekeepers — I speak from experience as I include myself in this group — complain about the price of miticides

That being the case, are there ways to save money?

Are there ways that don't involve DIY 'don't tell the bee inspector and did I weigh it correctly?' remedies, or eBay purchases from exotic locations at dubious prices?

Pay attention to use-by dates

Usually, with miticides, the more you buy, the more you save. I've included a couple of examples in the table above.

The price per hive per treatment for Api-Bioxal drops ~30% if you purchase the largest sachet size. Similar savings are possible with Formic-Pro, reducing the price from absolutely outrageous to just daylight robbery.

Have I forgotten you've only got 3 hives?

No (and nor have the suppliers 😉).

Three is an awkward number where miticides are concerned, as many are sold in 5 or 10 hive multiples.

There are two obvious solutions here:

- club together with some other beekeepers to share the cost (and benefits) of purchasing more for less

- use miticides that are individually packaged, or can be re-sealed and have a long shelf-life

Let's deal with those in reverse order.

All miticides have a use-by date, but they also have a use within N days/weeks of opening the packet.

But, be careful, N might be zero 😞.

The most recent sachet of Apivar I opened had a use-by date of May 2025, but carried the words “Use immediately after first opening and discard any unused product”.

That would make treating three hives cost £10 each.

Ouch!

However, Apiguard comes in individual sachets, and you use one at a time sequentially, meaning the unused ones are still 'valid' up to the use-by date. The suppliers are currently listing Apiguard with a use by date of September 2026.

Coordinating miticide purchases … and treatment?

Alternatively, 'bulk' purchases — between 2 or 3 friends, or an entire association — should allow savings to be made, both by reducing costs and wastage.

Three beekeepers managing 10 hives in total could purchase two sachets of Apivar and one small packet of Api-Bioxal, for a total outlay of £76 (i.e. £7.60/hive/year) and have no wastage.

An entire association could save on both Apivar and Api-Bioxal costs for its members (by my estimates getting the outlay down to ~£6.74/hive, or lower if they negotiate with the suppliers). Some do.

I can see two possible additional benefits from these larger scale miticide purchases.

The first is the potential for coordinated treatment over a wider geographic area. In a different life I did some research on this and showed it was possible to reduce Varroa levels at the landscape scale by coordinated treatment. All (or at least most) miticide instructions carry advice to coordinate treatment (which might be in a single apiary, but could be a larger area), but I know almost nobody who practises this.

Secondly, alternating treatment in sequential years — amitraz one year, thymol the next etc. — will help reduce the development and selection of miticide-resistant Varroa populations.

Of course, this requires beekeepers to get organised and coordinate their activities.

This takes time and enthusiasm.

Although time may be limited in May and June, enthusiasm should be abundant.

Why not think now about your late-summer and winter miticide treatments? Doing so now might save on the costs of the treatments themselves, and using them as part of your all-important winter preparations will mean you lose fewer (or no) colonies overwinter, and have strong colonies next spring.

So, more savings 😄.

Ignoring miticides until you need them, using less than you should, or applying them at the wrong time is either false economy, or tempting fate.

And now I'm off to check that bait hive …

OK, you've read this far, so it must have been useful, interesting, or entertaining … so why not sign up as a subscriber?

Subscribers to The Apiarist receive an emailed newsletter most weeks on bees and beekeeping.

Paid subscribers (sponsors) receive additional sponsor-only content, including the separate short-form BeeMusings newsletter.

Why not sign up and join them now?

{{1}}: I texted my neighbouring beekeeper to suggest she check for swarm cells, though the approach/departure direction appeared to be from elsewhere.

{{2}}: Depending very much on your locality and the local forage available to your bees.

{{3}}: Some associations commendably have maximum nuc pricing to avoid either undercutting or price gouging. I think this is a good practice and should be encouraged.

{{4}}: With the latter calculation based upon the inflated beekeeping supplier prices for oxalic acid; 10 kg currently costs about £50 from a chemical supplier … if you have an EPP licence.

Join the discussion ...