If it quacks like a duck ...

… it might be a trapped virgin queen.

I discussed the audio monitoring of colonies and swarm prediction last week. Whilst interesting, I remain unconvinced that it is going to be a useful way to predict swarming.

And, more importantly, that replacing the manual aspects of hive inspections is desirable. I’m sure it will appeal to hands off beekeepers, though I’m not sure that’s what beekeeping is about.

However there was a second component to what was a long and convoluted publication {{1}} which I found much more interesting.

Listening in

If you remember, the researchers fitted hives with sensitive accelerometers and recorded the sounds within the hive for two years. Of about 25 colonies monitored, half swarmed during this period, generating 11 prime swarms and 19 casts.

In addition to the background sounds of the hive, with changes in frequency and volume depending upon activity, some colonies produced a series of very un-bee-like toots and quacks.

Have a listen …

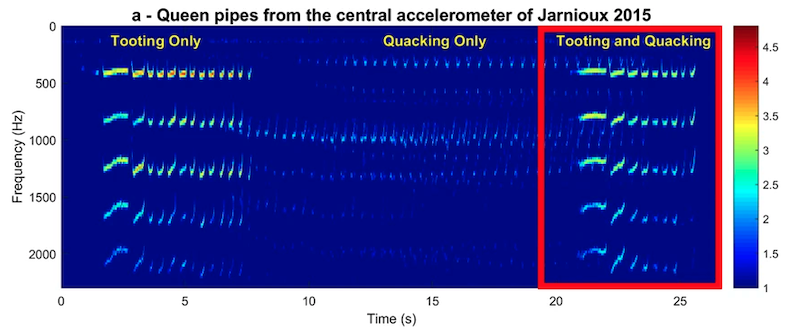

The audio starts with tooting, the quacking starts around 8-9s, and there’s overlapping tooting and quacking from near the 21s mark.

Queen communication

I’ve previously introduced the concept of pheromone-based communication within the hive. For example, the mated queen produces the queen mandibular and queen footprint pheromones, the concentrations of which influence the preparation and development of new queen cells.

Tooting and quacking is another form of queen communication, this time by virgin queens in the colony.

It’s not unusual to hear some of these sounds during normal hive inspections, but only during the swarming season and only when the colony is in the process of requeening.

If you rear queens, and in my experience particularly if you use mini-mating nucs, you will regularly hear “queen piping” – another term for the tooting sound – a day or so after placing a mature charged queen cell into the small colony.

But we’re getting ahead of ourselves.

How does the queen make these sounds?

Queen piping or tooting

Queen tooting has been observed. The queen presses her thorax tight down against the comb and vibrates her strong thoracic wing muscles. Her wings remain closed. The comb acts as a sounding board, amplifying the sound in the hive (and presumably transmitting the vibrations through the comb as well).

This doesn’t happen just anywhere … the virgin queen is usually near the cell she has recently emerged from.

And this swarm cell is usually on the periphery of a frame.

This is because the laying queen only rarely ventures to the edges of frames, so the concentration of her footprint pheromone is lower in this area, eventually resulting in queen cells being produced there

In their study, accelerometers embedded in the periphery of comb were able to detect much stronger tooting and quacking signals, supporting the conclusions of Grooters (1987) {{2}} who had first published studies on the location of piping queens.

Queen piping is usually recorded at around 400 Hz and consists of one or more 1 second long pulses, followed by a number of much shorter pulses. In previous studies the frequency of tooting had been shown to be age-related. It starts at ~350 Hz and rises in frequency to around 500 Hz as the virgin queen matures over several days.

Compare the image above with the audio file linked further up the post. The tooting is followed by an extended period of quacking, and then both sounds occur at the same time.

Going quackers

The duck-like quacking is presumably also made by queens vibrating their flight muscles while pressed up against the comb.

I say ‘presumably’ as I don’t think it has been observed, as opposed to heard.

The reason for this is straightforward, the queens that are quacking are still within the closed queen cell.

Quacking is a lower frequency sound (is this because of the confines of the queen cell, the way the sound is produced, or the ‘maturity’ of the queen’s musculature?) but has also been shown to increase in frequency – from ~200 Hz to ~350 Hz – the longer the queen remains within the cell.

Afterswarms = casts

Before discussing the timing of tooting and quacking we need to quickly revisit the process of swarming. I’ve covered some of this before when discussing the practicalities of swarm control, so will be brief.

- Having “decided” to swarm the colony produces swarm cells. Usually several.

- Weather permitting, the prime swarm headed by the original laying queen leaves the hive, on or around the day that the first of the maturing queen cells is capped.

- Seven days after the cell was capped the first of the newly developed virgin queens emerges.

- If the colony is strong, this virgin also swarms (a cast swarm). Some texts, including the publication being discussed, call these afterswarms.

- Over the following hours or days, successively smaller cast swarms may leave the hive, each headed by a newly emerged virgin queen.

Not all colonies produce multiple cast swarms, but initially strong colonies often do.

From a beekeeping point of view this is bad news™. It can leave the remnants of the original colony too weak to survive and potentially litters the neighbourhood with grapefruit, orange and satsuma-sized cast swarms.

Irritating 🙁

Whether it’s good for the bees depends upon the likelihood of casts surviving. The very fact that evolution has generated this behaviour suggests it can be beneficial. I might return to this point at the end of the post.

Tooting timing

The Grooters paper referred to earlier is probably the definitive study of queen tooting or piping. The recent Ramsey publication appears to largely confirm the earlier results {{3}}, but has some additional insights on colony disturbance during inspections {{4}}.

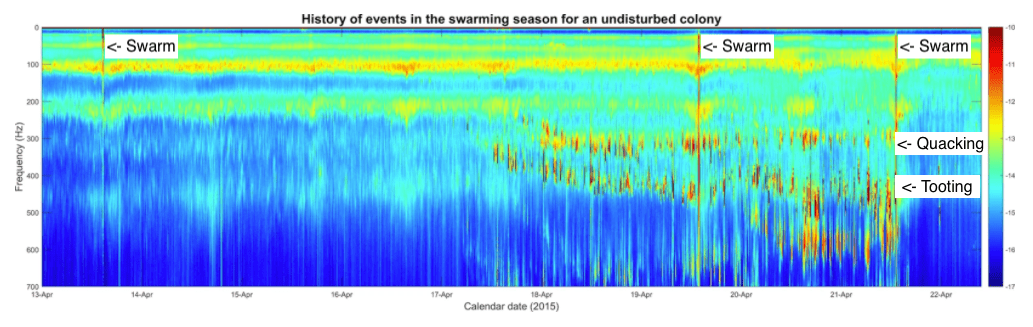

Here is the acoustic trace of an undisturbed colony producing a prime swarm and two casts.

I’ve added some visible labels to the image above indicating the occurrence of tooting and quacking in an undisturbed naturally swarming colony.

- The prime swarm exited the hive on the afternoon of the 13th. No tooting had been recorded before that date.

- On the 17th tooting starts and increases in frequency over the next two days.

- Quacking starts 6 hours after the tooting starts.

- The first cast swarm (afterswarm) exits the hive on the 19th and is followed by a three hour break in tooting.

- Tooting and quacking then continue until the second cast swarm on the afternoon of the 21st.

So, in summary, tooting starts after the prime swarm leaves and stops temporarily when the first cast leaves the hive. Quacking starts after the tooting starts and then continues until the last swarm leaves the hive.

Why all the tooting and quacking?

The timing of queen tooting is consistent with it being made by a virgin queen that has emerged from the cell. The cessation of tooting upon swarming (the first afterswarm) suggests that the virgin left with the swarm. The restarting of tooting a few hours later suggests a new virgin queen has been released from another cell and is announcing her presence to the colony.

In previous studies, Grooters had shown that replaying the tooting sound to mature virgin queens actively chewing their way out of a queen cell delayed their emergence by several hours. This delay allowed the attendant workers to reseal the cell and obstruct her emergence for several days.

These timings and the behaviour(s) they are associated with suggest they are a colony-level communication strategy to reduce competition between queens.

The newly emerged virgin queen toots (pipes) to inform the workers that there is ‘free’ queen in the colony. The workers respond by holding back emergence of other mature queens.

If all (or several) of the virgin queens emerged and ran around the hive simultaneously they would effectively be ‘competing’ for the hive resources needed for successful swarming i.e. the workers.

By controlling and coordinating a succession of queen emergence, a strong colony has the opportunity to generate one, two or more cast swarms whilst sufficient workers remain in the hive. It presumably helps ensure the casts are of a sufficient size to give them the best chance of survival.

At what point does this succession stop or break down? One possibility is that this happens when there are insufficient workers to prevent additional virgin queens from emerging.

Unanswered questions

Why do mature virgin queens within the cell quack? It is clearly a response to tooting, rather than being standard behaviour of a soon-to-emerge queen.

Is the quacking to attract workers to help reseal the cell?

I suspect not. At least, I suspect there is a more pressing need to attract the workers. After all, wouldn’t it be easier for the queen to simply stop chewing her way out for a few hours?

Isn’t there a risk that a quacking cell-bound queen might attract the virgin queen running around ‘up top’ who might attempt to slaughter her captive half-sister?

Possibly, so perhaps the workers that are attracted to the quacking cell also protect the cell, preventing the loose virgin queen from damaging the yet-to-emerge queens.

This would make sense … if the virgin leaves with a cast, the workers that will remain must be sure that there will be a queen available to head the colony

And finally, back to the tooting. I also wonder if this has additional roles in colony communication. For example, what other responses does it induce in the workers?

Does the increasing frequency of tooting inform the workers that the virgin is maturing and that they should ready themselves for swarming? Perhaps tooting above a certain frequency induces workers to gorge themselves with honey to ensure the swarm has sufficient stores?

In support of this last suggestion, studies conducted almost half a century ago by Simpson and Greenwood {{5}} concluded that a 650 Hz artificial piping sound induced swarming in colonies containing a single mobile (i.e. free) virgin queen.

Casts

The apparently self-destructive swarming where a colony generates a series of smaller and smaller casts seems to be a daft choice from an evolutionary point of view.

Several studies, in particular from Thomas Seeley, have shown that swarming is a risky business for a colony … and that the majority of the risk is borne by the swarm, not the parental colony.

87% of swarmed colonies will rear a new queen and successfully overwinter, but only 25% of swarms survive. And the latter figure must only get smaller as the size of the swarms decrease.

One possibility is that under entirely natural conditions a colony will not undergo this type of self-destructive swarming. Perhaps it is a consequence of the strength of colonies beekeepers favour for good nectar collection or pollination?

Alternatively, perhaps it reflects the way we manage our colonies. Ramsey and colleagues also record tooting and quacking from colonies disturbed during hive inspections. In at least one of these their interpretation was that there were multiple queens ‘free’ in the hive simultaneously, presumably because workers had failed to restrict the emergence of at least one virgin queen.

So, perhaps hive inspections that (inadvertently) result in the release of multiple virgin queens are the colonies that subsequently slice’n’dice themselves to oblivion by producing lots of casts.

I can only remember one colony of mine doing this … and it started days after the previous inspection, but that doesn’t mean the disturbance I created during the inspection wasn’t the cause.

I’d be interested to know of your experience or thoughts.

Colophon

The title of this post is derived from the Duck Test:

If it looks like a duck, swims like a duck, and quacks like a duck, then it probably is a duck.

This probably dates back to the end of the 19th Century. It’s a form of abductive {{6}} reasoning or logical inference. It starts with an observation or set of observations and then seeks to find the simplest and most likely conclusion from those observations. In comparison to deductive reasoning, logical inference does not lead to a logically certain conclusion.

Inevitably, Monty Python stretched the logical inference a little too far in the Witch Logic scene from Monty Python and the Holy Grail:

What do you do with witches? Burn them! And what do you burn apart from witches? Wood! So, why do witches burn? ‘cos they’re made of wood? So; how do we tell if she is made of wood? Build a bridge out of ‘er! Ah, but can you not also make bridges out of stone? Oh yeah. Does wood sink in water? No, it floats! It floats! Throw her into the pond! What also floats in water? Bread! Apples! Very small rocks? Cider! Gra-Gravy! Cherries! Mud! Churches? Churches! Lead, Lead. A Duck! Exactly. So, logically… If she weighs the same as a duck, she’s made of wood… and therefore… a witch!

{{1}}: Ramsey, M., Bencsik, M., Newton, M.I. et al. The prediction of swarming in honeybee colonies using vibrational spectra. Sci Rep 10, 9798 (2020).

{{2}}: Grooters, H. J. (1987) Influences of queen piping and worker behaviour on the timing of emergence of honeybee queens. Insec. Sociaux 34(3), 181–193.

{{3}}: I suspect the part of the paper on tooting and quacking was below some sort of self-imposed (or journal imposed) minimal publishable unit, and was therefore lumped together with the swarm prediction stuff simply to get it published.

{{4}}: Which I’m going to skip as it doesn’t add much to the understanding of the overall story.

{{5}}: Simpson, J. & Greenwood, S. P. Influence of artificial queen-piping sound on the tendency of honeybee. Apis Mellifera, colonies to swarm. Insec. Sociaux 21, 283–287 (1974).

{{6}}: Abducktive?

Join the discussion ...