Know your enemy

What less appropriate time is there, as we enter the festive season of goodwill, to provide a brief account of the incestuous and disease-riddled life cycle of the Varroa mite?

Happy Christmas ?

Varroa is the biggest enemy of bees, beekeepers and beekeeping. During the replication cycle the mite transfers a smorgasbord of viruses to developing pupae. One of these viruses, deformed wing virus (DWV), although well-tolerated in the absence of Varroa {{1}}, replicates to devastatingly high levels and is pathogenic when transferred by the mite.

Without colony management methods to control Varroa, mite and virus replication will eventually kill the colony.

I’ve written extensively on ways to control Varroa. Most of these have focused on early autumn and midwinter treatment regimes. However, next season I’m hoping to discuss some alternative strategies and will need to reference aspects of the life cycle of Varroa … hence this post.

What is Varroa?

Varroa destructor is a distant relative of spiders, both being members of the class Arachnida … the joint-legged invertebrates (arthropods). It was originally (and remains) an external parasite (ectoparasite) of Apis cerana (the Eastern honey bee) and – following cross-species transfer a century or so ago – Apis mellifera, ‘our’ Western honey bee.

Apis cerana, having co-evolved with Varroa, has a number of strategies to minimise the detrimental consequences of being parasitised by the mite.

Apis mellifera doesn’t. Simple as that {{2}}.

One hundred years is the blink of an eye in evolutionary terms and, whilst there are bees that have partial solutions – largely behavioural (small colonies and very swarmy) – they’re probably unable to collect meaningful amounts of honey {{3}}.

Varroa-resistant honey bees will probably evolve (as much as anything is predictable in evolution) but not in my time as a beekeeper … or possibly not until Voyager 2 leaves the Oort Cloud {{4}}.

And there’s no guarantee they’ll be any use whatsoever for beekeeping …

The replication cycle of Varroa

Varroa has no free-living stage during the life-cycle. The adult mated female mite exhibits two distinct phases during the life-cycle. It has a phoretic phase on adult bees and a reproductive phase within sealed (‘capped’) worker and drone brood cells. Male mites only ever exist within sealed brood cells.

I’m going to discuss phoretic mites in a separate post. I’ll concentrate here on the replication cycle.

The mated female mite enters a cell 15-50 hours before brood capping. Drone brood is chosen preferentially (at ~10-fold greater rates than worker brood) and entered earlier. Depending upon the time of the season and the levels of mites and brood, up to 70-90% of mites in the colony occupy capped cells.

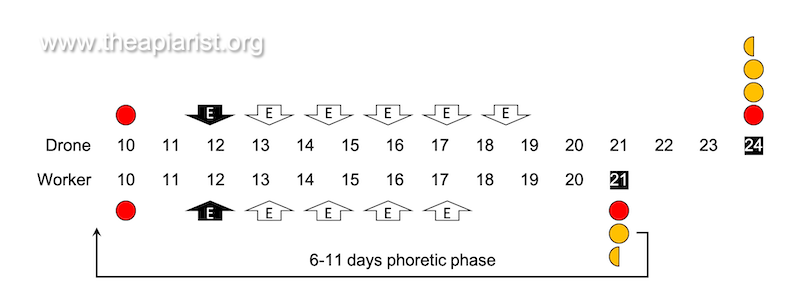

The first egg is laid ~70 hours after cell capping. This egg is unfertilized and develops into a haploid male mite. Subsequent eggs are fertilised, diploid, and so develop into female mites. These are laid at ~30 hour intervals.

Worker and drone brood take different times to develop. Therefore a typical reproductive cycle involves five eggs being laid in worker brood and six in drone brood. Not all of these eggs mature, their development being curtailed by the bee emerging as an adult.

There are all sorts of developmental stages involved in getting from an egg to a mature unfertilised mite, but these are not important in terms of the overall outcome. Mite-geeks love this sort of detail {{5}}, but we need to cut to the chase …

Keeping it in the family

The foundress ‘mother’ mite and her progeny all share a single feeding hole through the cuticle of the developing pupa.

What a lovely scene of family ‘togetherness’.

Male and female mites take 6.6 and 5.8 days respectively to develop to sexual maturity. Therefore the male mite reaches sexual maturity before the first of his sisters.

He then lurks around the attractive-sounding “faecal accumulation site” and mates with each of the (sister) females in turn.

What a little charmer ?

Male mites are short lived and the eclosion of the adult worker or drone curtails further mating activity, releasing the foundress mite and the mated mature daughters {{6}}.

Reproductive rate (mites per cell)

The three day difference in the duration of worker and drone development means that more mites are produced from drone cells than worker cells. Depending on conditions the reproductive rate is 1.3 – 1.45 in worker brood and 2.2 – 2.6 in drone brood.

Remember that the foundress is also released from the cell. She can go on to initiate one or two further reproductive cycles (or up to 7 in vitro). Consequently, the average yield of mature, mated female mites from worker and drone cells is a fraction over 2 and 3 respectively.

Before entering a fresh cell containing a late stage (5th instar) larva the newly-mated mites need to mature. They do this during the phoretic phase which lasts 5-11 days. Therefore the full replication cycle of the mite probably takes a minimum of about 17 days.

Exponential growth

Two to three mites per infested cell doesn’t sound very much. However, under ideal conditions this leads to exponential growth of the mite population in the colony. Assuming 10 reproductive cycles in 6 months, a single mite would generate a population of >1,000 in worker brood and >59,000 in drone brood {{7}}.

Fortunately (for our bees, not for the mites), ideal conditions don’t actually occur in reality.

Lots of things contribute to the reduction in reproductive potential. For example, only 60% of male mites achieve sexual maturity due to developmental mortality, drone brood is only available at certain times in the season, brood breaks interrupt the availability of any suitable brood and grooming helps rid adult bees of phoretic mites.

However, these reductions aren’t enough. Without proper management mite levels still reach dangerously high levels, threatening the long-term viability of the colony.

In the next few months I will discuss some additional opportunities for reducing the mite population.

In the meantime, as we reach the winter solstice, colonies in temperate regions may well be broodless and – as emphasised last week – this is an ideal time to apply a midwinter oxalic acid-containing treatment. This will effectively reduce mite levels for the start of the coming season.

Happy Christmas … unless you’re a mite ?

Colophon

Today is the winter solstice in the Northern hemisphere. This is actually the precise time when the Earth’s Northern pole has its maximum tilt away from the Sun. However, the term is usually used for the day with the shortest period of daylight and the longest period of night. In Fife, sunrise is at 08.44 and sunset at 15.37, meaning the day length is 6 hours and 53 minutes long.

With increasing day length queens will start laying again … but there’s a long way to go until winter is over.

{{1}}: In the absence of the mite DWV is transferred horizontally between bees during feeding and is asymptomatic.

{{2}}: A. mellifera does have some behavioural traits – grooming and so-called Varroa-sensitive hygiene (ability to clear infested/damaged pupae) – but these probably existed for aeons rather than evolving as a result of the recent species-jump of Varroa a century ago. This doesn’t mean that these traits aren’t useful, or cannot be potentially enhanced by selection, it just means that they didn’t evolve in response to mite infestation.

{{3}}: Small colonies collect little nectar and deliver little in ‘ecosystem services’ like pollination.

{{4}}: ~30,000 years at the present speed of 55,000 km/h.

{{5}}: Take my advice, don’t sit too near a mite-geek during a dinner party.

{{6}}: Immature unmated and mated progeny die through dehydration, they do not mature outside the capped cell.

{{7}}: Actually, these are an underestimate, based on the calculation xy where x is 2 or 3 for worker or drone brood respectively and y is 10 generations.

Join the discussion ...