Queen cells ... don't panic!

You’ve inspected your colony and discovered queen cells on one or more frames.

Queen cells …

Do you want the good news or the bad news?

The good news is that your colony is building up well and with a little careful management and luck you’ll be able to requeen them in about a month. A new, well-mated queen should ensure a strong colony going into the winter.

Result!

Alternatively, you could increase your colony numbers as – without exception – two is better than one.

The bad news is that your colony is rapidly outgrowing the space it has, it’s going to need some careful management and an appreciation of the development cycle of the queen. Unless you’re very lucky the colony will swarm and you’ll be left with one, significantly weakened, queenless colony.

Result … but probably not one you want.

Swarming isn’t a catastrophe. Things can usually be rescued, albeit with an interruption to colony development and honey production. However, it should be avoided if at all possible, not least because the lost swarm might cause problems for other people.

Play cups, charged queen cells and sealed queen cells

New queens are reared in specially shaped cells that are oriented vertically on the frame. They can be anywhere on the frame, but are often located on the edge of the comb, either at the sides or along the bottom.

Play cups …

Beekeepers make the distinction between cells of different sizes, different stages of development and – sometimes, though probably less reliably {{1}} – the type of cell (emergency, supercedure etc.) based upon their location.

Play cups are small cup-shaped cells that might subsequently be developed into queen cells. They’re regularly present in colonies that have no intention of swarming.

~3 day old queen cell …

After an egg is laid and hatches in one of these cup shaped cells the workers start feeding the developing larvae. At the same time the cell is extended, usually becoming broader and longer. Cells at this stage of development get a large amount of attention from workers in the hive and usually end up containing a thick bed of Royal Jelly in which the developing larvae floats. These are charged queen cells.

Charged queen cell …

Finally the cell is sealed and the larvae pupates before emerging as a virgin queen. During this period, particularly just before and after being sealed, the workers often sculpt the outer surface of the cell. Shortly before eclosion a thinner, darker brown ring can appear around the tip of the sealed cell.

Sealed queen cell …

Timing is everything

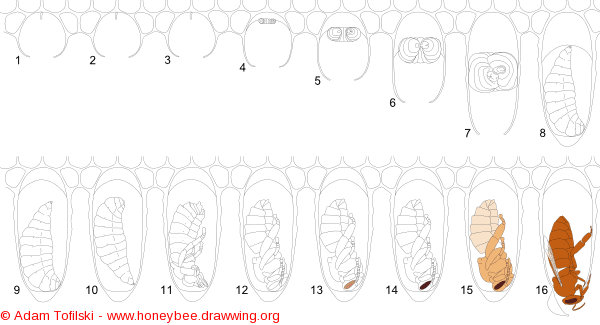

Queen development takes 16 days from egg laying to eclosed (emerged) adult virgin queen bee. The egg is laid in a cup and hatches on the 3rd day. The larva is fed copious amounts of Royal Jelly until day 8 when the cell is sealed or capped. About 16 days after the egg was laid the new queen emerges.

Queen development …

There’s a little bit of variation in these timings – hours, not days – and several diagrams show the queen cell sealed on the 9th day. In my previous description of queen rearing in a queenright colony (using the “Ben Harden“ method) I’ve stated that the cell is capped on day 9. That’s a convenient number to remember as she’ll emerge a week later.

We’re off !

Under normal circumstances the colony will swarm once the new queen cells are capped. The old queen and about 75% of the workers leave the hive for pastures new.

Poor weather can delay things, but it’s relatively rare to find sealed queen cells and the old queen still in residence … unless she’s clipped which delays things by a few days. However, clipping the queen does not stop swarming, it just buys you time and restricts the distance the swarm can go.

Clipped queen …

If the colony does swarm they often end up underneath the original hive. The queen crashes ignominiously to the ground as she leaves the hive. She then crawls up the leg of the hive stand and is joined by the flying bees beneath the floor. It’s a bit of a palaver, but you can then brush/encourage them into a skep and rehive them.

Weekly inspections

An understanding of the development cycle of the queen and the swarming behaviour of colonies explains why inspections on a seven day cycle make sense. If there are no queen cells on the first inspection there is little or no chance the colony will have swarmed on a sealed queen cell within the following seven days.

Since colonies headed by clipped queens tend to delay a bit before swarming it’s usually reckoned you can inspect on a 10 day cycle. Although most of my queens are clipped {{2}} I inspect on a 7 day cycle as it fits better with work commitments.

What to do if you find queen cells

Don’t panic …

Don’t panic.

Correctly determining the state of the colony now will ensure you take the correct course of action.

It’s not unusual for an inexperienced beekeeper to find one or more sealed queen cells in the colony and to immediately remove them all {{3}}.

However, if this novice beekeeper subsequently finds there’s no queen in the colony (unsurprising as she’s swarmed), no eggs in the colony (because she swarmed >3 days ago) and no young larvae in the colony (because they actually swarmed nearly a week ago) then the colony has no chance of raising a new queen without further intervention by the beekeeper e.g. by providing a ‘frame of eggs’ from another colony from which a new queen can be reared.

What I do depends upon what I find …

Play cups

I check to see if any have eggs in and then pinch them flat … mainly so I can tell if more have been made since the last inspection.

Charged queen cells

The first time I discover these I usually knock them all down and leave the colony another week.

This is not risk-free {{4}}.

Firstly … I check that the colony is queenright and that the queen is OK i.e. still laying at a reasonable rate, not being hassled by the workers and looking healthy. If I have any concerns about the queen I’ll start some form of swarm control (see below).

Secondly … It’s imperative to destroy all the charged queen cells. I therefore shake the bees off each frame and check the comb carefully … the sides, the bottom, the various nooks and crannies.

Everywhere.

Miss one charged cell and they’ll likely swarm within the next 7 days. Anything that looks like a queen cell gets squidged {{5}}.

Finally … if this is the second consecutive weekly inspection with charged queen cells I’ll start some form of swarm control (see below).

Don’t repeatedly rely upon knocking off every charged queen cell week after week after week.

You will miss one … I guarantee it. They will swarm.

Destroying charged queen cells is not swarm control

This should be engraved on every hive tool sold to new beekeepers 😉

I speak from experience 🙁

Sealed queen cells

Oops 🙄

They’ve probably swarmed. It’s therefore too late for swarm control.

However, I check for eggs and the queen. I might be lucky … poor weather may have prevented swarming {{6}}. Alternatively, the presence of eggs tells me they went in the last 3 days so I have an idea of the age of the sealed cell (so can calculate when the new queen will emerge).

Ideally I like to leave a colony with a single cell I know contains a developing pupae. Although you can open and reseal queen cells (Ted Hooper describes doing this in Introduction to Bees and Honey) to check they’re occupied, I’ve never bothered.

Instead, if there are large charged queen cells present I select one, mark the frame and then destroy all the sealed cells and unwanted charged unsealed cells. I can estimate to a day or so when the queen will emerge and so know when there’s likely to be a new mated queen in the hive.

Please support further articles by becoming a supporter or funding the caffeine that fuels my late night writing ...

Thank you

If there are eggs and young larvae but no other charged cells (rare), I’ll knock back the sealed cells and let them rear more, finally leaving them with one known charged cell after the next inspection.

Swarm control

This post is already too long … there are dozens of ways of doing this. Two already described in detail are vertical splits and the ‘classic’ artificial swarm. Both are pretty much foolproof if you can find the queen. Both are conservative and non-destructive … you can reunite colonies if either fails.

Vertical splits use less equipment and need less space, but involve some heavy lifting.

Pagdens’ artificial swarm requires a duplicate hive and more space but is gentler on your back.

Or make up a nuc with the old queen as a backup and leave the colony to rear a new queen. I’ll describe this approach in the future.

{{1}}: So I’m going to ignore this for the time being.

{{2}}: There are a couple I’ve yet to find this season and are likely to be late season supercedures from 2017.

{{3}}: There are many ways of doing this … pinch them between thumb and forefinger or tear them out with the hive tool to destroy them. If they’re wanted for another colony – and they often are – you can carefully cut them out, together with a generous piece of comb, using a small serrated knife.

{{4}}: I’m not necessarily recommending this course of action, just saying what I do.

{{5}}: Squidge … to squash, most often between ones fingers (and, interestingly, a term used in tiddlywinks).

{{6}}: In which case, don’t delay … implement some form of swarm control pronto.

Join the discussion ...