Ready, Steady ... Wait

Since you are reading an internet beekeeping site you are probably aware of the discussion fora like Beesource, BBKA, the Beekeeping Forum and Beemaster Forum.

Several of these have a section for beginners. The idea is that the beginner posts a simple beekeeping question and, hey presto, gets a helpful answer.

Of course, the reality is somewhat different 😉

The question might seem simple (“Should I start colony inspections this week?”), but the answers might well not be.

If there’s more than one answer they will, of course, be contradictory. The standard rule applies …

Opinions expressed = n + 1 (where n is the number of respondents {{1}})

… but these opinions will be interspersed with petty squabbles, rhetorical questions in return, veiled threats, comments about climate or location, blatant trolling and a long discourse on the benefits of native black bees/Buckfast/Carniolans or Osmia bicornis {{2}}

Finally the thread will peter out and the respondents move to another question … “When should I put the first super on my hive?”

Climate and weather

Although it might not seem helpful at the time, the comment about climate and location refers to an important aspect of beekeeping often overlooked by beginners {{3}}.

Climate and weather are related by time. Weather refers to the short term atmospheric conditions, whereas climate is the average of that weather.

Climate is what you expect, weather is what you get.

Climate and weather have a profound influence on our beekeeping.

We live on a small island bathed in warm water originating from the Gulf Stream. In addition, we are adjacent to a large land mass. The continent and the sea influence both our weather and climate.

For simplicity I’m going to only consider temperature and rainfall. The former influences the flowering period of plants and trees upon which the bees forage.

Both temperature and rainfall determine whether the bees can forage – if it’s too cold or wet they stay in the hive.

And adverse weather (strong winds, heavy rain) can make inspections an unpleasant experience for the bees … and the beekeeper {{4}}.

The North – South divide (and the East – West divide)

Compare the mean temperature in Fife (marked with the red star) with Plymouth (blue star). The average annual temperature is 8-9°C in Fife and 10-11°C in Plymouth. Although this seems to be a very minor temperature difference it makes a huge difference to the beekeeping season {{5}}.

As I write this (mid-April) I’ve yet to fully inspect a hive but colonies are swarming in the south of England, and have been for at least a week.

When I lived in the Midlands I would often start queen rearing in mid/late April {{6}} whereas here inspections might not begin until May in some years.

The 6° of latitude difference between Plymouth and Fife (~415 miles) is probably equivalent to 3-4 weeks in beekeeping terms.

In contrast to the oft-quoted view that ‘Scotland is wet’, Fife only gets about 66% of the rainfall of Plymouth (800-1000 mm for Fife vs. 1250-1500 mm for Plymouth).

However, there is an East – West divide for rainfall in parts of the country. I’m writing this in Ardnamurchan, the most westerly point of mainland Britain (yellow arrow), where we get about three times the annual rainfall as the arid East coast of Fife.

The rhythm of the seasons

The seasonal duties of the beekeeper are dependent on the weather and the climate. This is because the development of the colony is influenced by how early and how warm the Spring was, how many good foraging days there were in summer, the availability of sunny 20°C days for queen mating and the warmth of the autumn for late brood rearing.

And a host of other weather-related things.

All of which vary depending where your bees live.

And vary from year to year.

Which is why it’s impossible to answer the apparently simple question “When should I put the first super on my hive?” using a calendar.

“Beekeeping by numbers (or dates)” doesn’t work.

You have to learn the rhythm of the seasons.

Make a note of when early pollen (snowdrop, crocus, hazel, willow) becomes available, when the OSR and rosebay willowherb flowers and when migratory birds return {{7}}. The obvious ones to record are flowers or trees that generate most honey for you, but early- and late-season cues are also useful.

Most useful are the seasonal occurrences that precede key events in the beekeeping year.

Link these together with the recent weather and the development of your colonies. By doing this you will begin to know what to expect and can prepare accordingly.

If the OSR is just breaking bud {{8}} start piling the supers on. If cuckoos are first heard a month before the peak of the swarming period in your area make sure you prepare enough new frames for your preferred swarm control method.

And preparation is pretty-much all I’ve been doing so far this year … though I expect to conduct my first full inspections over the Easter weekend.

Degree days

While doing some background reading on climate when preparing this post I came across the concept of heating and cooling degree days. These are used by engineers involved in calculating the energy costs of heating or cooling buildings.

Heating degree days are a measure of how much (in degrees), and for how long (in days), the outside air temperature was below a certain level.

Conversely, cooling degree days are a measure of how much (in degrees), and for how long (in days), the outside air temperature was above a certain level.

You can read lots more about degree days on the logically-named degreedays.net , which is where the definitions above originated.

From a beekeeping point of view you can use this sort of data to compare seasons or locations.

Most ‘degree days’ calculations use 15.5°C as the certain level in the definitions above. This isn’t particularly relevant to beekeeping (but is if you are heating a building). However, degreedays.net (which have a bee on their BizEE Software Ltd. logo 🙂 ) can generate custom degree day information for any location with suitable weather data and you can define the level above or below which the calculation is based.

For convenience I chose 10°C. Much lower than this and foraging is limited.

The North – South divide (again)

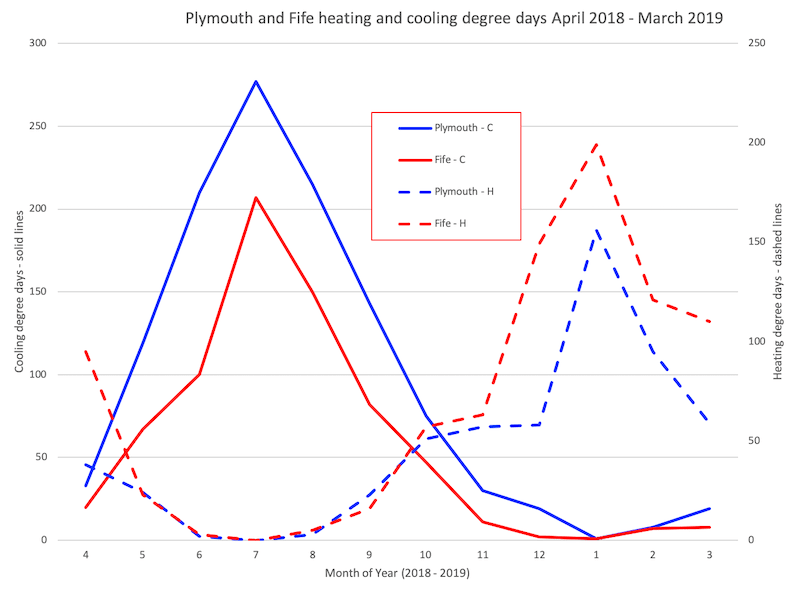

So, let’s return to swarms in Plymouth and the absence of inspections in Fife … how can we explain this if the average annual temperate is only a couple of degrees different?

Focus on the dashed lines for the moment. September to November (months 9, 10 and 11) were very similar for both Plymouth (blue) and Fife (red). After that – unsurprisingly – the Fife winter is both colder and longer. From December through to March the Plymouth line rises later, rises less far and falls faster. In Plymouth the winter is less cold, is shorter and – as far as the bees are concerned – the season starts about a month earlier {{9}}.

2018 in Fife was an excellent year for honey. After a cold winter (and the Beast from the East) colonies built up well and I harvested record amounts (for me) of both spring honey (in early June) and summer honey (in late July/early August).

I’ve no idea what 2018 was like for honey yields in Plymouth, but the cooling degree days (solid lines) show that it was warmer earlier, hotter overall and that the season lasted perhaps a month longer (though this tells us nothing about forage availability).

Of course it’s the longer, hotter summers and cooler, shorter winters that – averaged out – mean the average annual temperature difference between Plymouth and Fife is only a couple of degrees Centigrade.

Good years and bad years

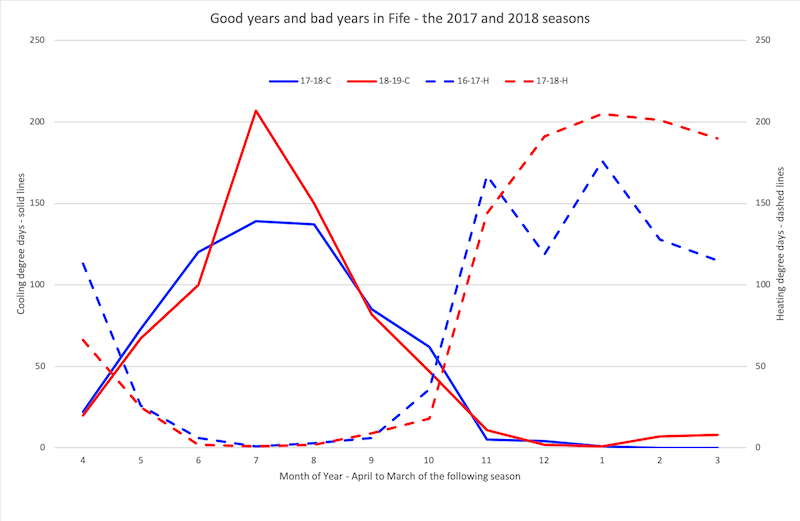

As far as honey is concerned the last two years in Fife have been, respectively, sublime and ridiculous.

2018 was great and 2017 was catastrophic.

How do these look when plotted?

The onset of summer (solid lines – the cooling degree days – months 4-6) and the preceding winter (dashed lines – the heating degree days – months 9-11) were similar – the lines are nearly superimposed.

The 2016-17 winter was milder and shorter than 2017-18. The latter was extended by arrival of the Beast from the East and Storm Emma which brought blizzards in late February and continued unseasonably cold through March.

However, the harsh 2017-18 winter didn’t hold the bees back and the 2018 season brought bumper honey harvests.

In contrast, the 2017 season was hopeless. It was cooler overall, but the duration of the season was similar to the following year {{10}}. Supers remained resolutely empty and my entire honey crop shared a single batch number 🙁

However, it wasn’t the temperature that was the main problem. It was the abnormally high rainfall during June.

Colonies were unable to forage. Some needed feeding. Queen mating was very patchy, with several turning out as drone laying queens later in the season.

The spring nectar flows were a washout and the colonies weren’t at full strength to exploit the July flows.

Let’s see what 2019 brings …

{{1}}: Remembering also that the respondent who expressed two opinions will also have contradicted themselves … and others.

{{2}}: I omitted the SBAi discussion forum from the list at the top of the page as it is rarely acrimonious, generally excellent and fabulously well-moderated :-)

{{3}}: Or, for that matter, many respondents to questions on the internet.

{{4}}: Unless the colonies are kept in a bee shed.

{{5}}: I’ll return to this at the end of the post …

{{6}}: And in one memorable year even earlier when I had mated queens by the first couple of days of May.

{{7}}: I saw my first house martins on 17th April this year.

{{8}}: And remember that strain variation and time of planting also determines when this happens – overwintered rape flowers before spring-sown.

{{9}}: Colonies in my bee shed develop earlier in the season than those outside in the same apiary and brood rearing continues later into the autumn.

{{10}}: Compare the solid lines in months 6-9.

Join the discussion ...