Latitude and longitude

Synopsis : Bees don’t use a diary. Colony development is influenced by local environmental conditions. These are largely determined by latitude and longitude but also vary from year to year. Understanding these influences, and learning how to read the year to year differences, should help you judge colony development. You’ll be better prepared for swarm prevention and control, and might be able to to identify minor problems before they become major problems.

Introduction

Writing a weekly post on beekeeping inevitably generates comments and questions. Over the last 5 years I’ve received about 2500 responses to posts and at least double that in email correspondence. That works out at ~30 comments or questions a week {{1}}.

Every one of them – other than the hate mail and adverts {{2}} – has received a reply, either online or by email.

Some are easy to deal with.

It takes just seconds to thank someone for a ”Great post, now I understand” comment, or to answer the ”Where do I send the cheque? question.

Others are more difficult … and the most difficult of all are those which ask me to diagnose something about their hive.

I almost always prefix my response by pointing out that this sort of online diagnosis is – at best – an inexact art {{3}}.

Think about it … is your definition of any of the following the same as mine?

- a strong colony {{4}}

- an aggressive colony

- a dodgy-looking brood pattern {{5}}

- a ‘large’ queen cell

Probably not.

Engaging in to and fro correspondence to define all these things isn’t really practical in a week containing a measly seven 24 hour days.

Geography

However, having stated those caveats, there’s still the tricky issue of geography.

Many correspondents don’t mention where the hive is – north, south, east, west (or in a couple of instances that they are in the southern hemisphere {{6}}).

Location has a fundamental impact on your bees. The temperature, rainfall, forage availability etc. all interact and influence colony development. They therefore determine the timing of what happens when in the colony.

And so this week I decided to write a little bit about the timings of, and variation in, environmental events that influence what’s going on inside the hive.

I’ll focus here on latitude and temperature as it probably has the greatest influence. My comments and examples will all be UK based as it’s where a fraction over 50% of the readers are, but the points are relevant in all temperate areas.

Latitude

Temperate climates – essentially 40°-60° north or south of the equator – experience greater temperature ranges through the year and have distinct seasons (at least when compared with tropical areas). Whilst latitude alone plays a significant role in the temperature range – smaller nearer the equator – the prevailing wind, altitude, sea currents and continentality {{7}} also have an important influence.

For starters let’s consider the duration of the year during which foraging might be possible. I’ll ignore whether there’s any forage actually available, but just look at the temperature over the season at the northern and southern ends of mainland Great Britain.

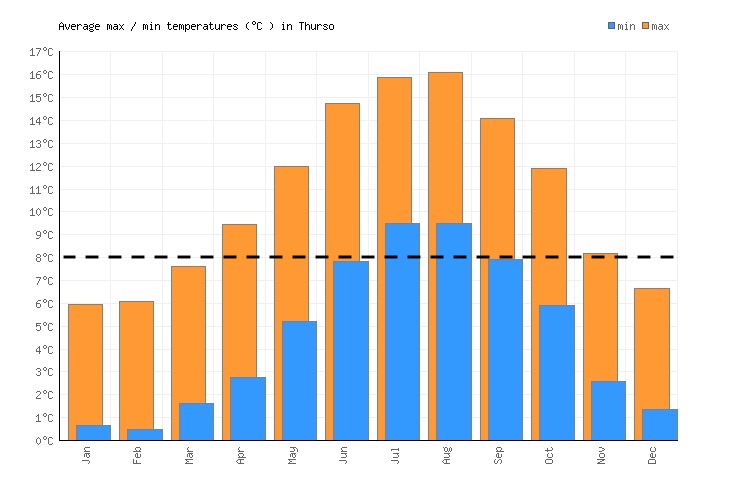

I arbitrarily chose Thurso (58.596°N 3.521°W) and Penzance (50.119°N 5.537°W) for these comparisons. Both are lovely coastal towns and both are home to native black bees, Apis mellifera mellifera {{8}}.

The lowest temperature I have observed my native black bees flying on the west coast of Scotland was about 8°C {{9}}. So, let’s assume that the ‘potential foraging’ season is defined by an average maximum daily temperature above 8°C.

How do Penzance and Thurso compare?

In Thurso there are eight months (November just squeezed in by 0.1°C) where the average maximum daily temperature exceeds 8°C.

In contrast, every month of the year in Penzance has an average maximum daily temperature exceeding 8°C.

Thurso and Penzance are just 950 km apart as the bee flies.

Forage availability

I don’t have information on the forage available to bees in Penzance or Thurso, but I’m sure that gorse is present in both locations. The great thing about gorse is that it flowers all year, or – more accurately – individual, genetically distinct, plants can be found every month of the year in flower.

Based upon the temperature it’s possible that Penzance bees could forage on gorse in midwinter and so be bringing fresh pollen into the hive for brood rearing.

However, further north, gorse might be flowering but conditions may well not be conducive for foraging.

Inevitably, warmer temperatures will extend the range of forage types available, so increasing the time during the year in which brood rearing can occur {{10}}.

In reality, at temperatures below 12-14°C bees start to cluster {{11}} and bees chilled to 10°C cannot fly. It’s unlikely much foraging could be achieved at the 8°C used in the examples above {{12}}.

The point is that different latitudes differ greatly in their temperature, and hence the forage that grows, the time it yields nectar and pollen, and the ability of the bees to access it.

Brood rearing

The availability of forage has a fundamental impact on the ability of the colony to rear large amounts of new brood.

It’s not until foraging starts in earnest that brood rearing can really ramp up.

Similarly, low temperatures in autumn, reduce the availability of nectars and ability of bees to forage, so curtailing brood rearing {{13}}.

And the ability to effectively treat mites in the winter is largely determined by the presence or absence of sealed brood. If there is sealed brood in the colony there will also be mites gorging themselves on the capped pupae. These mites are untouched by the ‘usual’ winter miticide, oxalic acid.

Therefore, effective midwinter mite management should be much easier in Thurso than Penzance.

I’ve not kept bees in either of those locations, but I know my bees in Fife (56°N) are reliably broodless at some point between late October and mid-December. Varroa management is therefore relatively straightforward, and Varroa levels are under control throughout the season.

In contrast, when I kept bees in Warwickshire (52°N) there were some winters when brood was always present, and Varroa control was consequently more difficult. Ineffective control in the winter results in higher levels of mites earlier in the season.

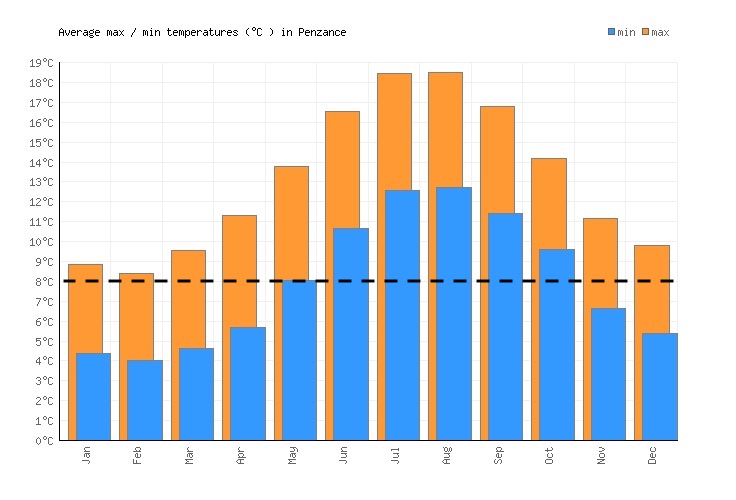

Brood rearing models

To emphasise the differences here are two images generated from Randy Oliver’s online Varroa Model, just showing the amounts of brood in all stages and adult bees {{14}}. The overall colony sizes and amount of brood reared are about the same, but the ‘hard winter’ colony (no foraging for five months) is broodless for a much greater period.

Without knowing something about the latitude and/or the likelihood of there being capped brood present in the hive, it’s impossible to give really meaningful answers to questions about winter mite treatment.

This also has a bearing on when you conduct your first inspections of the season.

It is also relevant when comparing what other beekeepers are discussing on social media – e.g. those ’8 frames of brood’ I mentioned last week. If it’s early April and they’re in Penzance (or Perigord) then it might be understandable, but if you’re in Thurso don’t feel pressurised into checking your own colonies as it may well be too early to determine anything meaningful.

Year on year variation

But it’s now approaching late April and most beekeepers will be starting to think/worry about swarm control.

When should you start swarm prevention and, once that fails, when must you apply swarm control?

Or, if you’d prefer to take a more upbeat view of things, when might you expect your bait hives to be successful and when should you start queen rearing?

Again, like almost everything to do with beekeeping, dates are pretty meaningless as your colonies are not basing their expansion and swarm preparations on the calendar.

They are responding to the environmental conditions in your particular locality and in that particular year.

Which brings me to year on year variation.

Not every year is the same.

Some seasons are warmer than others – the spring might be ‘early’ or there might be an ‘Indian summer’. In these instances foraging and brood rearing are likely to start earlier or finish later.

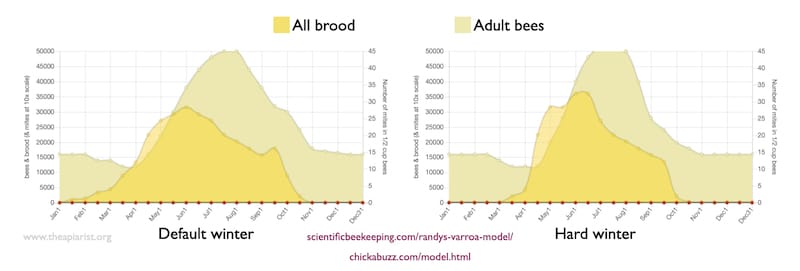

One way to view these differences is to look at the Met Office climate anomaly maps. These show how different the climate – temperature, rainfall, sunshine etc. – can be from year to year when compared to a 30 year average.

Here are the anomaly maps for the last two springs. For almost all of the country 2020 was unusually warm. Penzance was 1.5°C warmer than the 30 year average. In contrast, over much of the country, 2021 was cooler than the 1990-2010 average.

So when considering how the colony is developing it’s important to consider the local conditions.

Those Met Office charts are retrospective … for example, you cannot see how this spring compares with previous years (at least, not yet {{15}}.).

Rainfall

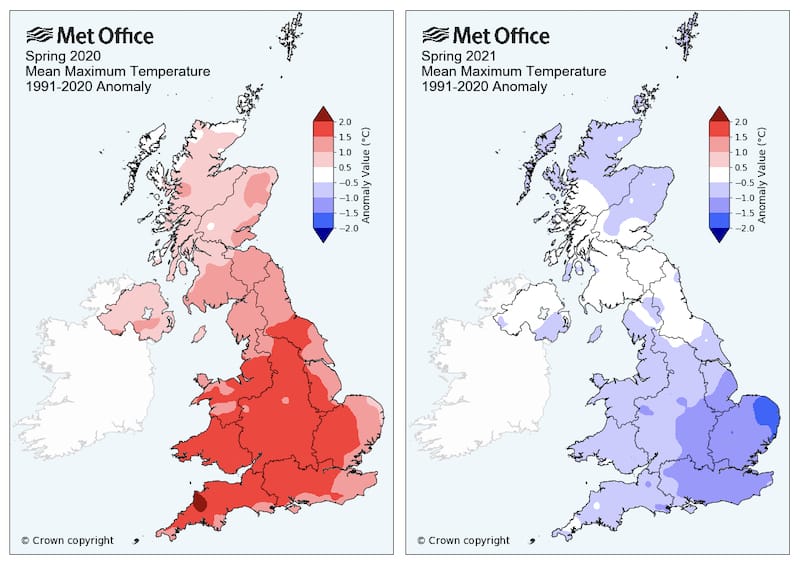

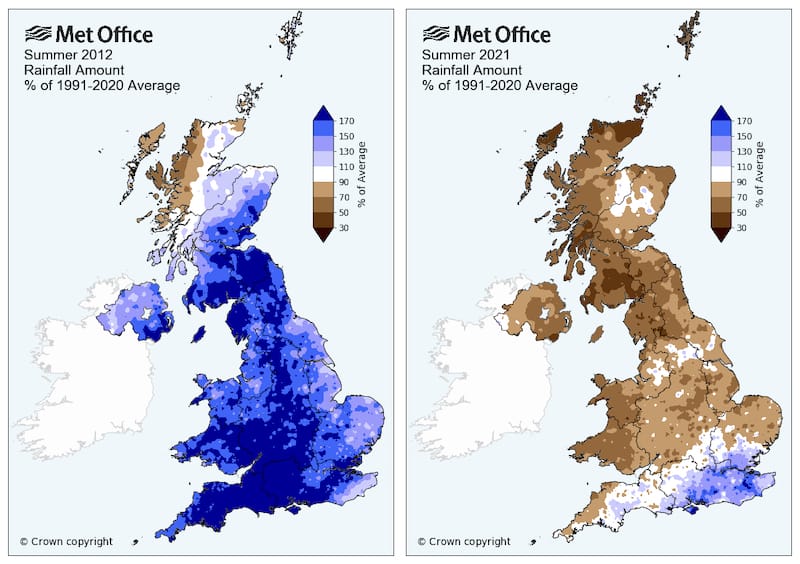

And, while we’re on the subject of anomalies … here are the rainfall charts for the summers of 2012 and 2021.

I suspect that both were rather poor years for honey. 2012 was – with the exception of Thurso! – exceedingly wet. My records for that year don’t include honey yield {{16}}.

Last year was generally dry, and very dry in the north and west {{17}}. Since a good nectar flow often needs moisture in the soil it may have been poor for many beekeepers.

It was my first full season on the west coast and the heather honey yield was disappointing (but it’s not a great heather area and I’ve nothing to compare it with … perhaps I’ll be disappointed every year?). However, I managed a record summer honey crop in Fife from a reduced number of hives. Quite a bit of this was from lime which I always think of as needing rain to get a good flow from, so perhaps the little rain we did have was at the right time.

Local weather and longitude

If you really want to know what the weather has been doing in your area you probably need something more fine-grained and detailed than a Met Office chart. There are very large numbers of ‘personal weather stations’, many of which share the data they generate with websites such as windy.com or wunderground.com.

Find one by searching these sites and you’ll be able to access recent and historical weather data to help you determine whether colony build up is slow because it’s been colder and wetter than usual. Or – if the conditions have been ideal (or at least normal) but the colony is struggling – whether the queen is failing, if there’s too much competition for forage in the neighbourhood, or if there might be disease issues.

Of course, judgements like these mean you need to have good records year on year, so you know what to expect.

My main apiary on the west coast has it’s own weather station.

To emphasise the local influence of prevailing winds and warm sea currents it’s interesting to note that my west and east coast apiaries – which are at almost the same latitude {{18}} – experience significantly different amounts of rainfall.

We had >270 mm of rain in November 2021 on the west coast, compared to ~55 mm on the east. In July 2021 the figures were 43 mm and 7 mm respectively.

All of which I think makes a good argument for rearing local bees that are better adapted to the local conditions {{19}}. That’s something I’ve discussed previously and will expand upon further another time.

Phenology

Rainfall charts and meteorological tables are all a bit dull.

An additional way a beekeeper can observe the progression of the season, and judge whether the colony is likely to be developing as expected, or a bit ahead or a bit behind, is to keep a record of other environmental events.

This is phenology, meaning ‘the timing of periodic biological phenomena in relation to climatic conditions’.

- Are frogs spawning earlier than normal?

- When did the first snowdrops/crocus/willow flower?

- Are the arrival dates of migrant birds earlier or later than normal?

I’m poor at identifying plants {{20}} so tend to focus on the animals. The locals – frogs, slow worms, toads, bats, butterflies, dragonflies – are all influenced by local conditions. Many don’t make an appearance until well into the beekeeping season.

Or perhaps I just don’t notice them?

In contrast, the avian spring migrants appear in March and April. These provide a good indication of whether the spring is ‘early’ or ‘late’.

For example, cuckoo arrived here in 2020 (a warm spring) on the 18th of April. In 2021, a cold spring, they didn’t make an appearance until the 24th.

This year, despite January to March being warmer than average, they have yet to arrive. The majority of GPS-tagged birds are still en route, having been held up by a cold start to April {{21}}, though some have just {{22}} arrived in southern Scotland.

Wheatear are also several days later this year than the last couple of seasons, again suggesting that the recent cold snap has held things back.

You can read more about arrival dates of spring migrants on the BTO website.

Beekeeping is not just bees

Much of the above might not appear to be much to do with beekeeping.

But, at least indirectly, it is.

Your bees live and work in a small patch of the environment no more than 6 miles in diameter. That’s a very small area (less than 30 square miles). The local climate they experience will determine when they can forage, and what they can forage on. In turn, this influences the timing of the onset of brood rearing in the spring (or late winter), the speed with which the colony builds up, the time at which winter bees start to be reared and the duration of the winter when it’s either too cold to forage or there’s nothing to forage on (or both).

As a beekeeper you need to understand these events when you inspect (and judge the development of) your colonies. Over time, with either a good memory or reasonable hive records, you can make meaningful comparisons with previous seasons.

If your colony had ’8 frames of brood’ in mid-April 2020 (a warm year) and your records showed they swarmed on the 27th, then you are forewarned if things look similar this season.

Conversely, if spring 2020 and this year are broadly similar (and supported by your comprehensive phenological records {{23}} ) but your bees have just two frames of brood then something is amiss.

Of course, the very best way to determine the state of the colony is to inspect it carefully. Understanding the environmental conditions helps you know what to expect when you inspect.

{{1}}: And, for popular posts and/or technical ’how to’ topics (and – Ahem! – the ones where I’ve got something wrong), often more.

{{2}}: Formally, there’s been no actual hate mail, though there have been a couple of highly critical comments and one or two shall we say blunt views expressed … or ‘incorrect’ opinions as I like to call them.

{{3}}: It’s sure as hell not science.

{{4}}: Five frames of brood or 15?

{{5}}: Yes, spotty we can agree on, but are the empty cells backfilled with nectar, or missed by the queen? Were the cells laid up and then uncapped and the pupae cannibalised?

{{6}}: The first question about queen cells in late November was perplexing.

{{7}}: i.e. the size of the landmass surrounding a location.

{{8}}: Actually, the Cornish Black bees project (not an endorsement) appears to be based in Falmouth, but is at almost an identical latitude to Penzance.

{{9}}: These bees are pretty hardcore … they also fly in the rain, though not in the rain at 8°C.

{{10}}: I’m not suggesting here that brood rearing cannot occur if there’s no pollen available from the environment, but the pollen stores in the hive are limited and a lot of midwinter brood rearing would soon deplete them if they are not being refilled.

{{11}}: At least, that’s the figure often quoted, though I regularly see broken clusters through the perspex crownboards in low double digit temperatures. See also some of the hive photos in the post last week which were taken when the temperature was about 9°C

{{12}}: If I’d used 10°C as the cutoff, the flying season in Thurso and Penzance would have been 6 and 8 months respectively.

{{13}}: Reduced foraging, and reduced brood rearing, is a trigger for winter bee production.

{{14}}: I’m going to discuss this software sometime later in the season.

{{15}}: Spoiler alert … January, February and March were all warmer than average for most of the country.

{{16}}: Perhaps they got washed away?

{{17}}: Though it’s worth noting that Thurso’s 30% summer average rainfall is still probably quite a lot of rain!

{{18}}: But are ~3° of longitude apart.

{{19}}: Like snorkels …

{{20}}: Though I can just about cope with crocus, snowdrop and willow!

{{21}}: They are in mostly mid-France … perhaps it’s Brexit paperwork?

{{22}}: Yesterday.

{{23}}: I often just scrawl these in my hive records.

Join the discussion ...