Resolutions

It’s that time of the year again. The winter solstice is long passed. Christmas has been and gone. The New Year is here.

Happy New Year ?

And New Year is a time to make resolutions (a firm decision to do or not to do something).

There is a long history of making resolutions at the turn of the year. The Babylonians promised to pay their debts and return borrowed objects at their New Year. Of course, their year was based on a lunar calendar and started with the first crescent moon in March/April, but the principle was the same.

Many New Year’s resolutions have religious origins … though the more recent trend to resolve to “drink less alcohol” or “lose weight“ are somewhat more secular.

About 50% of people in the western world make New Year’s resolutions. This figure is up from ~25% in the 1930’s. Perhaps success increases uptake?

Popular resolutions include improvement to: health (stop smoking, get fit, lose weight), finance or career (reduce debt, get a better job, more education, save more), helpfulness (volunteer more, give more to charity) or self (be less grumpy, less stressed, more friendly) etc.

But since this is a beekeeping website it is perhaps logical to consider what resolutions would lead to improvements in our beekeeping.

Beekeeping resolutions

The short winter days and long, dark nights are an ideal time to develop all sorts of fanciful plans for the season ahead.

How often are these promptly forgotten in the stifling heat of a long June afternoon as your second colony swarms in front of you?

The beekeeping season starts slowly, but very quickly gathers pace. It doesn’t take long before there’s not enough time for what must be done, let alone what you’d like (or had planned) to do.

And then there are all those pesky ‘real life’ things like family holidays, mowing the lawn or visiting relatives etc. that get in the way of essential beekeeping.

So, if you are going to make beekeeping resolutions, it might be best to choose some that allow you to be more proactive rather than reactive. To anticipate what’s about to happen so you’re either ready for it, or can prevent it {{1}}.

Keep better records

I’ve seen all sorts of very complex record keeping – spreadsheets, databases, “inspection to a page” notepads, audio and even video recordings.

Complex isn’t necessarily the same as ‘better’, though I’ve no doubt that proponents of each use them because they suit their particular type of beekeeping.

My notes are very straightforward. I want them to:

- Be available. They are in the bee bag and so with me (back of the car, at home or in the apiary) all the time. If I need to refer to them I can {{2}}. They are just printed sheets of A4 paper, stuffed into a plastic envelope. I usually write them up there and then unless I forget a pen, it’s raining and/or very windy or I’m doing detailed inspections of every colony in the apiary. In these cases I use a small dictation machine and transcribe them later that evening.

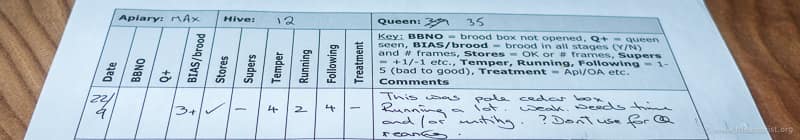

- Keep track of colonies and queens. I record the key qualitative features that are important to me – health, temper, steadiness on the comb etc. – using a simple numerical scoring system. Added supers are recorded (+1, +1, -2 etc) and there’s a freeform section for an additional line or two of notes. Colonies and queens are uniquely numbered, so I know what I’m referring to even if I move them between apiaries, unite them or switch from a nuc box to a full hive.

- Allow season-long comparisons ‘at a glance’. With just a line or two per inspection I can view a complete season on one page. Colonies consistently underperforming towards the bottom of the page usually end up being united in late August/early September.

- Include seasonal or environmental jottings. “May 4th – first swift of the year”, “June 7th – OSR finished”, “no rain for a fortnight”. These are the notes that, over time, will help relate the status of the colony to the local environment and climate. If the house martins, swallows and swifts are late and it’s rained for a month then swarming will likely be delayed. Gradually I’m learning what to expect and when, so I’m better prepared.

Monitor mites

Varroa remains the near-certain threat that beekeepers have to deal with every season. But you can only deal with them properly if you have an idea of the level of infestation.

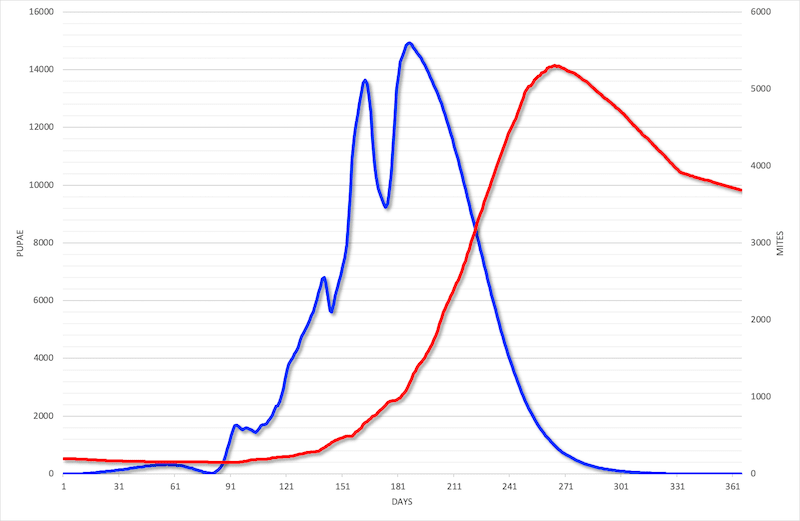

Varroa levels in the colony depend upon a number of factors including the rate of brood rearing, the proportion of drone to worker brood and the acquisition of exogenous mites (those acquired through the processes of drifting and robbing).

In turn, these factors vary from colony to colony and from season to season. As I discussed recently, adjacent colonies in the same apiary can have very different levels of mite infestation.

Additional variation can be introduced depending upon the genetically-determined grooming or hygienic activity of the colony, both of which rid the hive of mites.

Since the combined influence of these factors cannot be (easily or accurately) predicted it makes sense to monitor mite levels. If they are too high you can then intervene in a timely and appropriate manner.

Quick and effective ways to monitor mite levels

Any monitoring is better than none.

There are a variety of ways of doing this, some more accurate than others:

- Place a Correx tray under the open mesh floor (OMF) and count the natural mite drop over a week or so. Stick the counts into the National Bee Unit’s (appropriately named - but not longer available) Varroa calculator and see what they advise. There are quite a few variables – drone brood amounts, length of season etc – that need to be taken into account and their recommendation comes with some caveats {{3}}. But it’s a lot better than doing nothing.

- Uncap drone brood and count the percentage of pupae parasitised by mites. The NBU’s Varroa calculator can use these figures to determine the overall infestation level. The same caveats apply.

- Determine phoretic mite levels by performing a sugar roll or alcohol wash. A known number of workers (often ~300) are placed in a jar and the phoretic mites displaced using icing sugar or alcohol (car screenwash is often used). After filtering the sugar or alcohol the mites can be counted. Sugar-treated bees can be returned to the colony {{4}}. Infestation levels of 2-3% (depending upon the time of season) indicate that intervention is required {{5}}.

Overwinter nucs

If you keep livestock you can expect dead stock.

Unfortunately colony losses are an inevitability of beekeeping.

They occur through disease, queen failure and simple accidents.

Most losses are avoidable:

- Monitor mites and intervene before virus levels threaten survival of the colony.

- Check regularly for poorly mated or failing queens (drone layers) and unite the colony before it dwindles or is targeted by wasps or other robbers.

- Make sure you close the apiary gate to prevent stock getting in and tipping over hives … or any number of other (D’oh! Slaps forehead ? ) beekeeper-mediated accidents).

But they will occur.

And most will occur overwinter. This means that as the new season starts you might be missing one or two hives.

Which could be all of your colonies if you only have a two {{6}}.

Replacing these in April/May is both expensive and too late to ensure a spring honey crop.

Winter colony losses are the gift that keeps on giving taking.

However, if you overwinter an additional 10-25% of your colonies as 5 frame nucs (with a minimum of one), you can easily avoid disaster.

If you lose a colony you can quickly expand the nuc to a full hive (usually well before a commercially-purchased colony would be ready … or perhaps even available).

And if you don’t lose a colony you can sell the nuc or expand your colony numbers.

Sustainable beekeeping

If you’ve not watched Michael Palmer’s The Sustainable Apiary at the National Honey Show I can recommend it as an entertaining and informative hour for a winter evening.

Michael keeps bees in Vermont … a different country and climate to those of us in the UK. However, his principles of sustainable beekeeping without reliance on bought-in colonies is equally valid.

Overwintering nucs requires a small investment of time and money. The former in providing a little more care and attention in preparation for winter, and the latter in good quality nucleus hives.

I reviewed a range of nuc boxes six years ago. Several of these models have been discontinued or revised, but the general design features to look for remain unchanged.

Buy dense poly nucs for insulation, make sure the roof isn’t too thin and flimsy and choose one with an entrance that can be readily reduced to a “bee width” {{7}}. Choice (and quality) has improved over the last 5-6 years but I still almost exclusively use Thorne’s Everynuc. I bought 20 a few seasons ago and remain pleased with them, despite a few design weaknesses.

Beekeeping benefits

I do all of the above.

Having learned (often the hard way) that my beekeeping benefits, these habits are now ingrained.

I had about 20 colonies going into the 2019/20 winter, including ~20% nucs. All continue to look good, but it won’t be until late April that I’ll know what my winter losses are.

In the meantime I can review the hive notes from last season and plan for 2020. Some colonies are overwintering with very substandard queens (generally poor temper) because they’re research colonies being monitored for changes in the virus population {{8}}. They will all be requeened or united by mid/late May.

My notes mean I can plan my queen rearing and identify the colonies for requeening. I know which colonies can be used to source larvae from and which will likely be the cell raisers. The timing of all this will be influenced by the state of the colonies and the environmental ‘clues’ I’ve noted in previous years.

Of course, things might go awry before then, but at least I have a plan to revise rather than making it up on the spur of the moment.

I learned the importance of mite monitoring the hard way. Colonies unexpectedly crashing in early autumn, captured swarms riddled with mites that were then generously distributed to others in the same apiary. Monitoring involves little effort, 2-3 times a season.

So these three things don’t need to be on my New Year’s resolution list.

Be resolute

More people make New Year’s resolutions now than 90 years ago.

However, increasing participation unfortunately does not mean that they are a successful way to achieve your goals.

Richard Wiseman showed that only 12% of those surveyed achieved their goal(s) despite over 50% being confident of doing so at the beginning of the year.

Interestingly, success in males and females was influenced by different things. For men, incremental goal-setting increased the success rate {{9}} (I will write hive notes on every apiary visit, rather than Keep better notes). For women, the peer pressure resulting from telling friends and family increased success by 10%.

More generally, increased success in achieving the goals resulted from:

- Making only one New Year’s resolution – so perhaps the three things above is overly ambitious?

- Setting specific goals and avoiding resolutions you’re previously failed at.

My New Year’s (beekeeping) resolutions?

Since I’m a man, the chance of achieving my goals is not influenced by peer pressure so I’m not publishing them. We’ll have to see in 12 months whether I’m in the 12% that succeed … or the 88% that fail ?

{{1}}: Hint … experience suggests that “This year I’m not going to visit the relatives” is often not well received. You have been warned.

{{2}}: For example, ‘remember extra super for hive #23’.

{{3}}: It should be remembered that the above predictions are based on sampling and estimates, so the recommendation is a guidance to help the beekeeper make a decision.

{{4}}: Unfortunately bees bathed in alcohol cannot be returned :-(

{{5}}: I’ll discuss this method, and an alternative using CO2, later this year when I’ve had a chance to take some photographs.

{{6}}: And you should have at least two.

{{7}}: You’ll make these nucs up in summer and they are prone to being robbed out by wasps or strong neighbouring colonies.

{{8}}: I realise that perhaps doesn’t make sense. I can’t change the queen until the experiment is completed as it introduces another variable to the study. We’re monitoring changes in the virus population following interventions to reduce catastrophically high mite infestations.

{{9}}: By 22%.

Join the discussion ...