Spotty brood ? failing queen

I thought I’d discuss real beekeeping this week, rather than struggle with the high finance of honey sales or grapple with the monetary or health consequences of leaving supers on the hive.

After all, the autumn equinox has been and gone and most of us won’t see bees for several months 🙁

We need a reminder of what we’re missing.

Beekeeping provides lots of sensory pleasures – the smell of propolis on your fingers, the taste of honey when extracting, the sound of a full hive ‘humming’ as it dries stored nectar … and the sight of a frame packed, wall-to-wall, with sealed brood.

This is a sight welcomed by all beekeepers.

Nearly every cell within the laid up part of the frame is capped. All must therefore have been laid within ~12 days of each other (because that’s the length of time a worker cell is capped for).

However, the queen usually lays in concentric rings from the middle of the frame. Therefore, if you gently uncap a cell every inch or so from the centre of the frame outwards, you’ll see the oldest brood is in the centre and the most recently capped is at the periphery.

It’s even more reassuring if the age difference between the oldest and the youngest pupae is significantly less than 12 days. Hint … look at the eye development and colouration.

This shows that the queen was sufficiently fecund to lay up the entire frame in just a few days.

What are these lines of empty cells?

But sometimes, particularly on newly drawn comb, you’ll see lines of cells which the queen has studiously avoided laying up.

It’s pretty obvious that these are the supporting wires for the sheet of foundation. Until the frame has been used for a few brood cycles these cells are often avoided.

I don’t know why.

It doesn’t seem to be that the wire is exposed at the closed end of the cell. I suspect that either the workers don’t ‘prepare’ the cell properly for the queen – because they can detect something odd about the cell – or the queen can tell that there’s something awry.

However, after a few brood cycles it’s business as usual and the entire frame is used.

All of these laid up frames contain a few apparently empty cells. There are perhaps four reasons why these exist:

- Workers failed to prepare the cell properly for the queen to lay in

- The queen simply failed to lay an egg in the cell

- An egg was laid but it failed to hatch

- The egg hatched but the larvae perished

Actually, there’s a fifth … the cell may have been missed (for whatever reason) but the queen laid in it later and so it now contains a developing larva, yet to be capped.

What are all these empty cells?

But sometimes a brood frame looks very different.

Worker brood {{1}} is present across the entire frame but there are a very large number of missed cells.

Note: Ignore the queen cells on this frame! It was the only one I could find with a poor brood pattern.

This type of patchy or spotty brood pattern is often taken as a sign of a failing queen.

Perhaps she’s poorly mated and many of the eggs are unfertilised (but they should develop into drone brood)?

Maybe she or the brood are diseased, either reducing her fecundity or the survival and development of the larvae?

Sometimes spotty brood is taken as a sign of inbreeding or poor queen mating.

Whatever the cause, colonies producing frames like that shown above are clearly going to be less strong than those towards the top of the page {{2}}.

So, if the queen is failing, it’s time to requeen the colony …

Right?

Perhaps, perhaps not …

Which brings me to an interesting paper published by Marla Spivak and colleagues published in Insects earlier this year {{3}}.

This was a very simple and straightfoward study. There were three objectives, which were to:

- Determine if brood pattern was a reliable indicator of queen quality

- Identify colony-level measures associated with poor brood pattern colonies

- Examine the change in brood pattern after queens were exchanged into a colony with the opposite brood pattern (e.g. move a ‘failing queen’ into a colony with a good brood pattern)

If you are squeamish look away now.

Inevitably, measuring some of the variables relating to queen quality and mating success involve sacrificing the queen, dissecting her and counting ‘stuff’ … like viable sperm in the spermathecae.

Unpleasant, particularly for the queen(s) in question, but a necessary part of the study.

However, in the long run it might save some queens, so it may have been a worthwhile sacrifice … so, on with the story.

Queen-level variables in ‘good’ and ‘poor’ queens

By queen level variables I mean things about the queen that could be measured – and that differ – between queens with a good laying pattern or a poor laying pattern.

Surprisingly, good and poor queens were essentially indistinguishable in terms of sperm counts, sperm viability, body size or weight.

Poor queens i.e. those generating a spotty brood pattern, weren’t small queens, or poorly mated queens. They were also not more likely to have fewer than 3 million sperm in the spermathecae (a threshold for poorly mated queens in earlier studies).

Furthermore, the queens had no statistical differences in pathogen presence or load (i.e. amount), including viruses (DWV, Lake Sinai Virus, IAPV or BQCV), Nosema or trypanosomes (Crithidia).

Hmmm … puzzling.

Colony-level variables

So if the queens did not differ, perhaps colonies with spotty brood patterns had other characteristics that distinguished them from colonies with good brood patterns?

Spivak and colleagues measured pathogen presence and amount in both the good-brood and poor-brood colonies.

Again, no statistical differences.

So what happens when queens laying poor-brood patterns are put into a good-brood pattern hive?

And vice versa …

Queen exchange studies

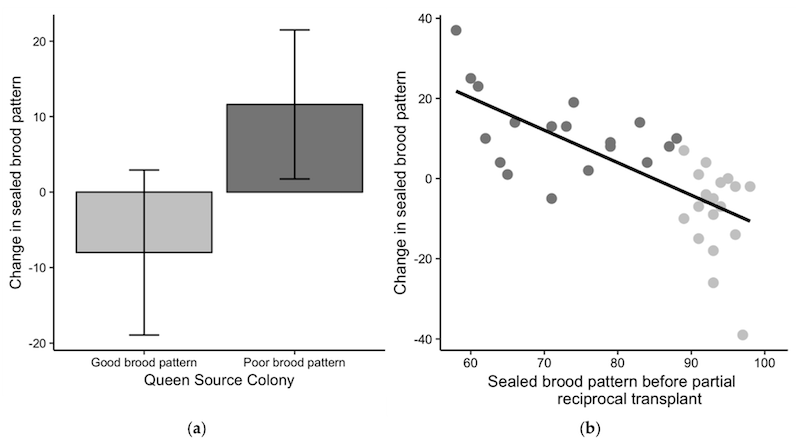

This was the most striking part of the study. The scientists exchanged queens between colonies with poor-brood and good-brood and then monitored the change in quality of the brood pattern {{4}}.

Importantly, they monitored brood quality 21 days after queen exchange. I’ll return to this shortly.

Queen from good-brood colonies showed a slight decrease in brood pattern quality (but not so much that they’d be considered to now generate poor brood patterns).

However, surprisingly, queens from poor-brood colonies exhibited a greater improvement in brood quality (+11.6% ± 9.9% more sealed cells) than the loss observed in the reverse exchange (-8.0% ± 10.9% fewer sealed cells).

These results indicate that the colony environment has a statistically significant impact on the sealed brood pattern.

Admittedly, a 10-20% increase (improvement) in the sealed brood pattern on the last frame photograph (above) might still not qualify as a ‘good brood pattern’ queen, but it would certainly be an improvement.

Matched and mismatched workers

Since exchanged queens were monitored just 21 days after moving them all the workers in the receiving hive were laid – and so genetically related to – the previous queen.

The authors acknowledge this and comment that it would be interesting to extend the period until surveying the hive to see if ‘matched’ workers reverted to the poor brood pattern (assuming that was what the queen originally laid).

This and a host of other questions remain unanswered and will undoubtedly form the basis of future studies.

The authors conclude that “Brood pattern alone was an insufficient proxy of queen quality. In future studies, it is important to define the specific symptoms of queen failure being studied in order to address issues in queen health.”

Notwithstanding the improvements seen in some brood patterns I suspect they would be insufficient to justify not replacing an underperforming queen … when considering the issue as a practical beekeeper i.e. there may be improvements but they were much less than could be achieved by replacing the queen from a known and reliable source.

But it might be worth thinking twice about this …

Insufficient storage space

In closing it’s worth noting that I’ve seen spotty or incomplete brood patterns when there’s a very strong nectar flow on and the colony is short of super storage space.

Under these conditions the bees start to backfill the brood box, taking up cells that the queen would lay in.

Usually this is resolved just by adding another super or two.

If there remains any doubt (about the queen) and you’ve provided more supers you can determine the quality of the laying pattern by putting a new frame of drawn comb into the brood nest.

The queen should lay this up in a day or two if she’s “firing on all cylinders”.

In which case, definitely keep her 🙂

{{1}}: Drone cells spotted randomly across the frame are a pretty-sure sign of laying workers … I’m solely discussing worker brood here.

{{2}}: And weak colonies are most likely to be robbed and less likely to produce a honey crop.

{{3}}: Lee et al., 2019 Is the brood pattern within a honey bee colony a reliable indicator of queen quality? Insects 10:12 – the full text of this paper is available free.

{{4}}: I’ve avoided discussion of this, but there are standard ways to quantify how good a good brood pattern is, or how bad a poor brood pattern is.

Join the discussion ...