Bad behaviour

Synopsis : Bad behaviour by bees – aggression, following and stability on the comb – may be transient or permanent. To recognise it you need to keep records and have hives to compare. Fortunately, these traits are easy to correct by requeening the colony.

Introduction

That’s a pretty generic title and it could cover a multitude of sins.

Slapdash disease management, insufficient winter feeding, poor apiary hygiene, siting bait hives near another beekeeper’s apiaries … even bee rustling.

However, I always try and write about a topic from direct practical experience.

If I did ever exhibit any of those examples of bad behaviour:

- The statute of limitations has passed 😉

- I don’t now and, conveniently, have forgotten the details anyway {{1}}

So, instead of discussing bad behaviour by beekeepers, I’ll write about badly behaved bees.

Nice bees

Most beekeepers have an idea of what ‘nice bees’ are like. It’s a {{2}} term that encapsulates the various characteristics that a beekeeper values.

These characteristics could include temper, stability on the comb, productivity (in terms of either/both bees or honey), frugality, colour and any number of other terms {{3}} that define either the appearance or behaviour of individual bees or, collectively, that of the colony.

Of course, all these terms are relative.

My definition of aggressive bees may well differ from what another beekeeper would consider (un)acceptable.

The relatively calm and stable bees in most of my hives could be defined as ’running about all over the place’ by someone who’s bees stick, almost immobile, to the comb.

This relativity is nowhere more apparent than when visiting the apiary of another beekeeper. I’m always a little wary of someone donning a beesuit 100 metres from the hives {{4}} while simultaneously claiming their bees are ’very friendly’.

These differences don’t matter if you keep your bees in an isolated location where other people – in particularly civilians (i.e. members of the general public) – won’t be impacted if your ’friendly bees’ are actually ’murderous psychopaths’.

However, they do matter if your bees are in an urban garden, or a shared allotment.

They also matter when making comparisons between colonies to determine which to split (so creating a new queen) and which – perhaps urgently – need requeening.

Transient or permanent?

For the purpose of the following discussion let’s consider that the ‘bad behaviour’ is aggression.

Here’s a screenshot from a YouTube video (from CapLock Apiaries, but now taken offline) which shows some really unpleasant bees. The final words (in this part of the video) by the beekeeper on the right is ”This queen has to die!”.

The brood boxes were stuck together, presumably because the colony is less regularly inspected and everything gets gummed up with propolis. The first comment {{5}} was

I’m new to bees and thought I found a hot wild hive today. Went to youtube to find some comparison. The hive I saw was absolutely docile in comparison to these guys, and the first wild hive I extracted are absolute angels!

Which emphasises the relative nature of behaviour.

I dislike aggressive bees so have no videos of my own showing this sort of behaviour {{6}}.

However, that doesn’t mean that my bees never show aggression … 😉

Weather, forage, handling, queenless … all can influence temper

Aggression – or defensiveness – can be a permanent feature of a colony or can appear transiently. In my view, the former is unacceptable under any circumstances {{7}}.

However, in response to environmental conditions or handling, a colony may become defensive. Again, the amount of ‘aggro’ varies. Some bees may just buzz a little more excitedly, others can go completely postal. If you are careful to only select from your better behaved stocks for splits and queen rearing you can usually avoid even transient unpleasantness.

Environmental factors that can influence the behaviour of a colony include the weather, the availability of forage and the gentleness and care exhibited by the beekeeper during inspections.

Queenless colonies may also be more aggressive, but all the comments in the post this week relate to queenright colonies.

Scores on the doors

There are two easy to achieve solutions that allow a beekeeper to make sense of the variation in any of these traits. These are:

- keeping good hive records to allow undesirable behaviour, or a gradual decline in behaviour, to be identified, and

- managing more than one colony so comparisons can be readily made

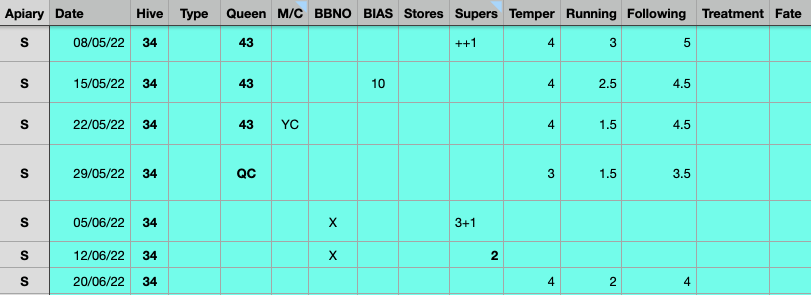

I score temper, running (stability on the comb) and following, but I know some who record a much greater range of characteristics.

Each are recorded on a 1 – 5 scale (worst to best, allowing half points as a ‘perfect 5’ is unattainable as the bees can always be better, whereas a 4.5 is a really good colony).

I also make a note of the weather. A colony may consistently score 4’s or better until you inspect them in a thunderstorm, but that’s OK because when you look back you’ll see that the conditions were woeful.

Compare and contrast

With just one colony you have no reference to know whether all colonies in the area are suffering because there’s a dearth of nectar, or if this colony alone is a wrong ‘un.

With two colonies things get easier.

Increasingly – for reasons I’ll discuss in a future post – I think three is probably the minimum optimum number.

The more you have the easier it is to identify the outliers … the exceptional (whether good 🙂 or bad 🙁 ). That should be qualified by stating the more you have in one location as the local environment may differ significantly between apiaries.

The great thing about hive records is that they provide a longer retrospective view. You can overlook the hammering you received from a colony last week {{8}} if there are a long list of 4’s over the last 3 months.

They also allow you to observe trends in behaviour.

Growing old disgracefully

I’ve recently noticed that a couple of my colonies are markedly less well behaved now we’re reaching mid-season than they were throughout 2021 or the beginning of this year. I think at least one has (actually had, as it was requeened last week) a 2020 queen.

As the queen ages the behaviour of the colony has gradually changed.

I crudely classify my colonies into thirds – good, bad or indifferent. Anything ‘bad’ is requeened as soon as I have a suitable queen available (or the larvae to rear one).

These ‘declining’ colonies were never worse than indifferent last year but, as they’ve expanded this spring, are now firmly in the ‘bad’ category. I presume this is consequence of the combination of the influence of the queen’s pheromones and the size of the colony {{9}}.

Whatever … I think all it really demonstrates is that consistently taking even cursory hive records is useful.

The colonies I’m referring to above haven’t become more aggressive (though this can happen). The characteristic I’ve seen change the most is the steadiness of the bees on the comb.

It’s worth noting here that colony size can fundamentally impact behaviour. A well-tempered nuc can develop into a big, strong and unpleasant colony. In contrast, the nucs I prepare from ‘indifferent’ colonies during swarm control and requeening don’t appear to generally improve much in temperament.

If I’m conducting swarm control on the third ‘bad’ tirtile {{10}} the queen is despatched so I never get to experience the performance of the resulting nucleus colony 😉

Aggression

I’ve discussed aggression above and covered it in more general terms previously. There are several studies of the genetics of aggression, usually by GWAS (Genome Wide Association Studies) of Africanised bees which can be significantly more bolshy than anything I’ve encountered in the UK {{11}}. The colony shown in the video cited above is Africanised.

A recent study analysed individual aggressive bees {{12}} and compared them with pollen-laden foragers from the same colony. However, they failed to identify any genetic loci associated with aggression.

In contrast, by ‘averaging’ the genetics of hundreds of aggressive or passive (forager) bees, the scientists identified a region of the genome that – if originating from European honey bees – was more likely to result in gentle bees. Conversely, if this region is Africanised, the colony was more likely to be aggressive {{13}}.

Hive genetics, not individual genetics

This is a really interesting result {{14}} as it means that, even if individual bees are Africanised and potentially aggressive, if the majority of the colony is European-like (and so gentle) the individual Africanised bees are unlikely to be aggressive.

Aggression is therefore a consequence of hive genetics, rather than individual genetics.

Neat.

Aggression in psychotic UK colonies (which, by definition, are not Africanised) may have a different genetic explanation, though some of the genes involved may be similar. Since aggression can manifest itself in several different forms – jumping up from the frames, buzzing around your head, response to sudden movement, targeting dark colours etc. – I suspect there may be multiple genes involved in the sensing or threat response.

Following

Some aggressive bees – particularly those that buzz agitatedly around your head during an inspection – also have the profoundly unpleasant trait of following you out of the apiary … down the track … back to the car … or even into the house.

The very worst of these lull you into a false sense of security by flying off, only to return in a lightning-fast kamikaze strike as soon as you remove your veil.

I consider ‘following’ a worse trait than overt aggression at the hive.

I’m suited and booted’ at the hive. Ready for anything … ’Come on if you think you’re hard enough’.

At least, I am if I’ve remembered to zip my veil up properly 😉

But 15 minutes later, when I should be contemplating a cuppa, I don’t want to be pestered by bees dive bombing my head.

Looking for trouble

Followers don’t necessarily just follow.

They can initiate long-range and unprovoked attacks on individuals just walking near the hive.

I think this is an example of bad behaviour that should not be tolerated.

If you think it’s bad as a beekeeper, just imagine how unpleasant it is for passers by.

Sometimes it’s difficult to identify which of several hives is showing this trait in an apiary. To confirm it, change the order of hive inspections, leaving the likely suspect to last. If the followers don’t appear until the final inspection you have your answer.

If they’re present before that you either guessed wrong or – Eek! – have more than one hive behaving badly.

I’ve seen many aggressive colonies that showed little or no tendency to follow. Conversely, I don’t remember seeing followers that were not from an aggressive colony. I presume this means that the genes involved are distinct but linked.

Whether different or not … they’re unwanted. Any colonies of mine showing overt aggression or following are requeened. Perhaps 5% of my colonies each season are requeened for this reason.

Running

Remember back to your early days of beekeeping when you had to ’find the queen’ and were faced with this … {{15}}

I estimate there are about 1200-1300 bees on the face of that frame {{16}}. There are the same amount on the other side.

All of the bees are moving.

Of course, this makes it much easier to find the queen as she moves differently to the workers on the frame. I’m probably not alone in sometimes struggling to ‘find the queen’ on a photograph of a frame when I rarely have trouble locating her on a frame in my hands {{17}}.

However, the more the workers move, the more difficult it gets.

Spot the queen

See if you can spot the queen on this frame of relatively sedate bees:

And what about this frame of more mobile bees? It’s worth noting there are only about half the total number of bees on this second frame.

OK, I cheated. Only the first frame has a queen on it. She’s in the middle near the bottom of the frame, moving left to right {{18}}.

The top frame is pretty standard in terms of ‘running’ (shorthand for the stability of bees on the frame) in my hives. The bottom video is nothing like the worst I’ve seen, but (if consistently like this) it’s certainly a reason to score the colony down and requeen them from a more stable line.

Inspections

Bees running around on the frame certainly make locating the queen more tricky.

However, as I’ve written elsewhere, you don’t need to find the queen unless you need to do something with her. The presence of eggs is usually sufficient to tell you the colony is queenright (assuming there are no big, fat queen cells or a queen corpse on the open mesh floor 🙁 ).

The reason I dislike bees that are not stable on the comb is because they make inspections more difficult. They prevent you clearly seeing eggs and larvae so you have to shake the bees off the frame, thereby overloading the next frame you look at with agitated bees.

Furthermore, the bees must have somewhere to run to … which usually means they run onto the frame lugs, and then your hands and – in the worst cases – up your forearms.

In addition, they run over each other, forming heavier and heavier ‘gloops’ {{19}} of bees that eventually become too heavy, lose their grip and fall … onto the top bars of the frames you have yet to inspect, onto the ground, or into the top of your boots.

Running appears to be a feature which isn’t influenced much by environmental conditions, perhaps other than a chilly and gusty wind {{20}}.

Better bees

There are two good things about aggression, following and running:

- these behaviours are easy to identify; you can easily tell if the colony is too hot for comfort, or if your neighbour complains repeatedly about getting chased by bees, or you’re plagued with ‘gloopy’ bees that make inspections a pain. Remember, there’s no standard to compare them to, no ‘reference colony’. All that matters is how they’re viewed by anyone that interacts with them. If they’re too defensive, if they bother you away from the hive or are too mobile, then score them down in your hive records. If they remain the same for the next two to three weeks, or don’t improve when the weather/forage picks up, then make plans to do something about it.

- all these undesirable traits can be easily corrected by replacing the queen. Four to six weeks after requeening the characteristics of the colony will reflect those of the new queen. Of course, this only works if you source a good quality queen – either by rearing your own or purchasing one {{21}}, or by ensuring that the colony raises its own queen from larvae sourced from a high quality colony. While you’re at it do yourself and your neighbouring beekeepers a favour and fork out any drone brood in the misbehaving colony.

It really is as easy as that.

Incremental but steady improvement

Over a few years the quality of your bees will improve.

Of course, with open mating you’ll occasionally get rogue colonies. However, as the average quality improves, you’ll have a greater choice of colonies from which to source larvae.

Over time you’ll need to recalibrate your scoring system. In five years a 3/5 will be a much improved colony over a 3/5 now.

When you next (reluctantly) open a bolshy colony, struggle to find the queen because of the wriggling mass of bees on the frames and are then stung repeatedly as you take your veil off by the car, think of it as an opportunity.

You have now recognised the problem and you already know the solution 😉

Note

I’ve chosen aggression, following and running as three easy to spot traits that can be, just as easily, fixed. There are other examples of bad behaviour that may well be unfixable. There’s a dearth of nectar in my west coast apiary until the lime flowers and robbing is a problem {{22}}. Although robbing is a variable characteristic (amongst different strains of bees) I doubt it could be excluded completely by requeening. Selection would be time consuming, being dependent upon environmental conditions. However, the ‘fix’ is again relatively straightforward … keep very strong colonies, feed late in the evening (if needed) and physically protect colonies with reduced entrances and/or robbing screens. Robbing is an example of bad behaviour by bees where the solution is almost entirely the responsibility of the beekeeper.

{{1}}: Full disclosure … I’m certainly guilty of the first two in the dim and distant past, I could still do better on the third and I don’t try and poach bees with my bait hives or steal hives.

{{2}}: Slightly insipid?

{{3}}: See note at the end.

{{4}}: Or worse, putting the veil on in the car.

{{5}}: When I accessed the video.

{{6}}: It’s not that I don’t video them … I don’t have any as I consistently select from my calmer stocks.

{{7}}: And I do not believe the ’better at collecting honey’ tales, which may instead be explained by the cursory or non-existent inspections aggressive colonies get.

{{8}}: When you were heavy handed returning the supers.

{{9}}: But that’s not much more than an ill-educated guess. It’s certainly not just colony size as this is their second full season.

{{10}}: Amusingly, autocorrect changes this to ‘turtle’ which somewhat alters the meaning …

{{11}}: See The Killer Bee Nightmare for a thoroughly unscientific account.

{{12}}: They identify these by bashing on the side of the hive and collecting stinging bees from black velvet squares placed around the hive.

{{13}}: For lots more details see See Avalos et al., (2020). Genomic regions influencing aggressive behavior in honey bees are defined by colony allele frequencies. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 117:17135-17141.

{{14}}: And deserves a post of its own.

{{15}}: Clearly, not this specific frame, as I photographed it in mid-Fife last weekend, but you get the idea.

{{16}}: They’re not really overlapping and there are one or two areas of comb visible. A fully covered frame probably has over 3000 bees adhering.

{{17}}: Unless of course I really need to find her.

{{18}}: Sorry … she is on the lower frame as well, but she ran around the back in the time it took me to set up the video.

{{19}}: Yes, officially that is the collective noun for bees hanging from the bottom of a frame.

{{20}}: I think that’s a hint to either choose a better day, or build a bee shed.

{{21}}: And I’d strongly recommend you do the former as you have a lot more control over quality.

{{22}}: As a beekeeper – or the colony being robbed – this is a problem. For the colony doing the robbing it’s the solution.

Join the discussion ...