Supply and demand

I believe that the importation of bees is detrimental to the quality of beekeeping in the UK. I think the beekeeping associations – national and local – should do more to discourage imports, that they should strongly encourage rearing local bees, and that they should have more emphasis on promoting the practical skills necessary for sustainable beekeeping in the UK.

This post was going to be called something like “Benefits of a ban” but I think the present title better reflects the problems in UK beekeeping and my views that readily available imported bees actually reduces the standard of beekeeping in the UK. The ban mentioned in the provisional title refers of course to a (potential at the time of writing) ban on the importation of bees and queens due to the recent discovery of Small Hive Beetle (SHB) in southern Italy.

Will there be a ban on imports and is this post relevant if there is no ban?

The European Union allows free trade between member states. However, it might be possible to impose a ban temporarily under Article 36 of the Lisbon Treaty which allows import restrictions for “the protection of health and life of humans, animals or plants”. However, whether there is a ban imposed to prevent SHB entering the country or not, I believe that the importation of bees is detrimental to the standard of beekeeping in the UK.

Executive summary

This is a longer-than-usual article, so here’s a summary in four easy-to-digest points:

- Thousands of queens and packages of bees are imported into the UK annually to meet the demands of; i) newly trained beekeepers, ii) beekeepers who lose stocks overwinter, or iii) beekeepers wanting to increase of improve their stocks.

- Our temperate climate provides a five month window for queen rearing. This creates a supply and demand problem, with maximum demand at a time when supply is limited. Cheap imported bees and queens act as a disincentive to rebalance this supply and demand.

- If imports were not available we would have to become better beekeepers, raising more nucs for overwintering, managing and meeting expectations for newly trained beekeepers, improving colony health and hence overwintering success and raising many more quality locally bred queens. Conversely, if the supply and quality of local bees and queens was better in the UK there would be fewer imports needed. We are in a Catch22 situation.

- Sustainable UK beekeeping (i.e. beekeeping that is no longer reliant on imports) does not mean reductions in numbers of colonies or numbers of beekeepers. Instead it requires, and would result in, an improvement in practical beekeeping skills.

That’s it in a nutshell … however, if you want the unabridged version, read on.

Local bees

Introduction and disclaimers

I would support a ban on the importation of bees and queens … not only from Italy, but from other countries as well. My primary reason in supporting such a ban is to restrict the chance that Small Hive Beetle (SHB) will arrive here. I fully appreciate that there are some commercial beekeeping operations that would likely be decimated by such a ban. In particular, it would destroy the business model of the commercial suppliers of early season queens and nucleus colonies (nucs). This is clearly undesirable on an individual basis and I regret the impact a ban would have on the livelihood of the individuals concerned. However, I consider this business model exploits underlying weaknesses in UK beekeeping and a ban would have long-term benefits in the creation of better beekeepers practising a more sustainable type of beekeeping in the UK.

My support for a ban is not to increase the number of queens I sell each season. My queen rearing is very much a hobby-sized activity, limited by my full-time employment, unpredictable deadlines and regular absences on the conference circuit. In many seasons – 2014 being a case in point – I barely generated enough queens for my own use. I would gain nothing from a ban on imports. In contrast, I think UK beekeepers and beekeeping have a lot to gain from becoming more self-sufficient.

UK imports of bees and queens

Annual imports …

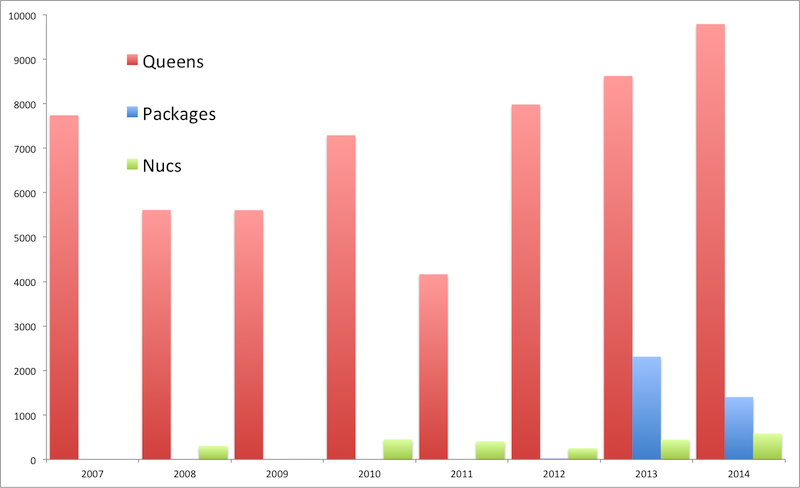

Thousands of queens raised overseas are imported to the UK every year (data from NBU but original link broken by their website 'reorganisation'). In 2014 alone nearly 10,000 queens were imported from Slovenia, Greece, Italy, Denmark and Cyprus (only listing the countries from which >1000 queens were imported). In addition a further 580 nucs and 1402 ‘packages’ were imported. I’m assuming that the National Bee Unit (NBU) defines a package in the same way they do in the USA – a mesh-sided shipping box containing 1-2kg of bees and a caged queen. 2014 saw the greatest number of imports of the last 8 years and there has been a steady increase since 2007, with queen imports only numbering less than 5000 in 2011. Why is demand so high?

Demand

Beekeeping has seen a recent rise in popularity, with hundreds of new beekeepers being trained every year in associations across the country. Many courses recruit 30-50 trainees each winter. Not all these fledgling beekeepers will end up getting their own bees – some accompany partners, some discover they’re allergic to stings and some are horrified the first time they’re suited up and standing next to an open hive – however, many of them do. Inevitably this generates a large demand for nucs early in the season to satisfy the enthusiasm of these new trainees. I was no different … I completed a course between January and March and then waited impatiently for a nuc to be ready. I bought a 5 frame nuc headed by an imported queen from an association member and started my beekeeping in mid-May. Demand for imports is likely to be generated by new trainees, compounded by the recent increase in the popularity of beekeeping and the timing of ‘Begin Beekeeping’ courses.

Annual colony losses

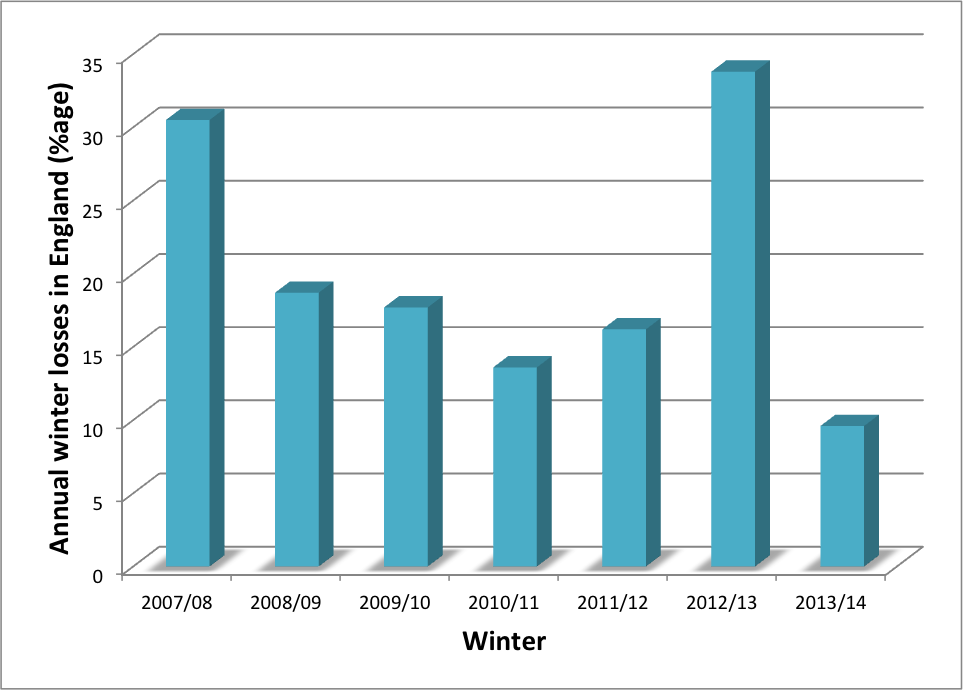

Over the last 7 years overwintering colony losses in England have averaged about 20% with – unsurprisingly – the greatest losses during the hardest/longest winter (2012/13). Inevitably some beekeepers, particularly those who are inexperienced or who have only one hive, might lose all their colonies. The most significant cause of overwintering colony loss is high levels of the parasitic mite Varroa and the consequent high level of pathogenic viruses such as Deformed Wing Virus. Understandably, enthusiastic beekeepers want to replace their overwintering losses, again driving up demand for bees early in the season.

I think there are additional potential causes of demand, though these are perhaps spread throughout the season. These are beekeepers a) wanting to increase their stocks or b) improve their stocks by replacement of an existing queen with a particular strain chosen for perceived docility, honey yield or a number of other reasons. There may also be additional demand to replace failing queens – drone layers for example – often identified when the colony is first opened in spring. Enthusiastic newcomers to beekeeping (perhaps entering their second year) as well as beekeepers who have had bees for many years probably contribute to this demand for imported bees and queens to increase or improve stocks.

In addition to the demand from ‘amateur’ beekeepers there is additional demand from some bee farmers, by which I mean individuals who make some or all of their living from honey production and pollination services (rather than individuals who import bees for resale). For example, £200,000 was provided by the Scottish government to import package bees after the 2012/13 winter. I know some bee farmers are entirely self-sufficient, raising queens and nucs to make increase, to replace their own losses and to sell if there is excess. However, with the exception of the large number of packages imported to Scotland over the last two years I have no idea how many bee farmers are reliant on imports. Since hobby beekeepers far outnumber bee farmers I will restrict the majority of my comments to this sector – a group that presumably also includes all newcomers to beekeeping.

Supply

Where do bees come from? In the absence of imports the demand for new queens, nucs and colonies would have to be met by taking advantage of the natural ways that bees reproduce i.e. by splitting strong colonies that are at risk of swarming, by capturing swarms that escape and by forcing the bees to raise one or more new queens by making a colony queenless (or at least think it’s queenless). Since splitting colonies reduces the foraging workforce it may impact on the amount of honey generated; in a normal season a beekeeper generally must choose between making new bees or making honey from any one colony.

Queen cells …

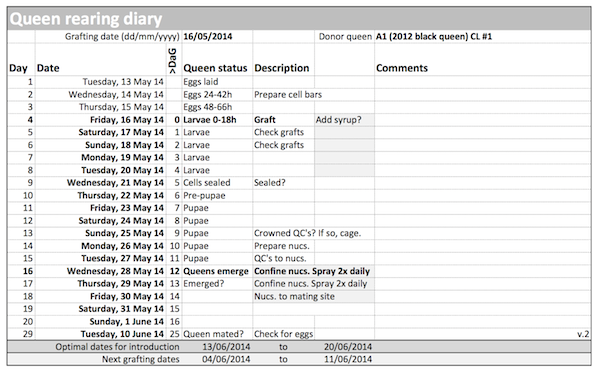

The rate limiting step in making new bees is the provision of newly mated queens. This generally requires warm, settled weather and fertile drones. In this area (the Midlands) we sometimes have suitable weather in April, but rarely have mature drones until May. In contrast, it’s not unusual to have both drones and good weather in September. Therefore home-grown bees – whether mated queens, nucs (and possibly swarms) – should be readily available in the five months May to September. Inevitably these dates cannot be precise – it’s good to let a newly mated queen demonstrate a good laying pattern which takes 7-14 days after she first gets going. Over the last five years the earliest and latest dates I’ve had queens mated on was about the 22nd of April and September respectively.

Mid- to late May or early June is probably 4-6 weeks too late for the peak demand for new queens and nucs. It’s during this critical early season period that overwintering losses and failed queens are detected, it’s the time when keen new beginners want their first bees and when the more experienced want to increase their colony numbers to exploit on the summer flows. The supply of locally-raised bees is currently unlikely to meet this early season demand due to weather restrictions on queen mating.

How can we better match supply and demand?

Or, more importantly, how do we match supply and demand without resorting to imported bees and queens every year? This is unlikely to be solved overnight, but there are several very obvious solutions that would help both meet the demand and improve local beekeeping.

Matching supply and demand requires a combination of increasing supply and reducing demand at critical points in the season. Effectively this should result in supply and demand balancing out over the course of the season. I suspect that the overall demand for new bees and queens could be relatively easily met from locally, or at least UK-raised, bees and queens. However, our temperate climate limits supply at the time of current highest demand. This needs to be addressed to achieve sustainability in UK beekeeping. Dealing with the four types of demand identified above in turn, here are some potential solutions:

- Bees for beginners. One obvious solution would be for associations to only train as many beekeepers as they can realistically provide overwintered nucs for the following spring. This would have a number of immediate benefits. It would generate revenue for the association members who provided the nucs. The revenue might also be shared with the association who trained the new beekeeper – they after all ‘created’ the buyer – potentially offsetting the financial losses of a reduction in the total numbers taking the training course. Furthermore, as established members recognise the annual demand from new trainees and invest in the equipment and skills needed to provide the nucs, increased numbers of beginners could again be accommodated on winter training courses. Since the nuc would be provided from locally-raised bees, they should be from a trusted and disease-free source, suited to local conditions and they could be inspected before purchase. If the nuc was overwintered the queen would presumably be well-established and her quality would be obvious. If the nuc was generated early in the same season the beginner would have to wait a little longer, but could be mentored during this period, even working alongside the experienced beekeeper to generate the nuc and monitor its development. Mentoring of beginners and their nucs (and in due course colonies) should then be extended throughout the first season to include the important preparation for overwintering, which takes us to the second cause of high early season demand for new queens and nucs.

- Bees to replace overwintering losses. Some losses are perhaps inevitable. However, they can certainly be minimised by good preparation for the winter. This starts as early as midsummer by careful attention to the following points; queen vigour, colony health, stores and the hive. Taking these in the reverse order, it goes without saying that the hive should be watertight, secure and protected against damage (for example, from grazing stock or woodpeckers). There should be sufficient stores present in the hive, either from syrup or fondant fed early enough and generously enough for the brood box to be stuffed at the beginning of winter. Knowing when to start feeding requires experience – too soon and you’re needlessly increasing your expenditure (the bees will still be foraging), too late and the colony may not lay down enough stores and so starve overwinter. During the winter it is also essential to ensure that the stores are not exhausted, by regularly ‘hefting’ the hive and providing fondant as required. It’s critical that the health of the colony is good going into the winter. This primarily means monitoring the Varroa mite numbers regularly during the season, minimising the mite load in August/September – to help raise a generation of bees for overwintering with low viral loads – and treating again in mid-winter during the broodless period to further reduce mite numbers. Weak colonies in mid/late summer are unlikely to overwinter well – there’s little point in mollycoddling them and (assuming they are healthy) it is almost always better to cull the queen and unite them with a stronger colony instead. The stronger colony will benefit and the weak colony, even if it did survive, would have been slow to develop in the spring. Finally, young vigorous queens generally lay later into the autumn, overwinter better and lay earlier and more strongly the following spring. Therefore it makes sense to replace ageing queens in the summer, rather than risk losing the colony due to her failing in the winter. This doesn’t necessarily mean culling her … she could be moved to head a nuc for overwintering for example, keeping a desirable line going for queen rearing the following season. Ted Hooper (in Guide to Bees and Honey) was a strong advocate of the benefits of young queens for overwintering success, recommending requeening in early September.

- Making increase. With a little planning and preparation it is possible to exploit the natural tendency of strong colonies to swarm in April-June to make increase. Although this might reduce honey yield it works with the bees to increase colony numbers. With experience, it’s usually possible to split a well-timed nuc from a strong colony without significantly impacting nectar gathering, with the nuc likely to build up to a full colony for overwintering. In addition, any area with reasonable numbers of beekeepers (and just look on BeeBase to see how saturated your local area is … there are 207 apiaries within 10km of my main out apiary) is likely to yield a number of swarms that will need collecting or can be caught in bait hives. If you divide colonies about to swarm or collect/attract swarms you might end up with swarmy bees, and you have no control of the quality of bees you acquire. However, queen rearing is not difficult and it is easy to requeen swarmy colonies or swarms of dubious quality … which takes us neatly on to improvement of stock.

- Stock improvement. Why is an open-mated queen purchased in early May for £40 and flown 1600 miles from Southern Italy likely to be better quality than a locally-bred queen from an association member or group who have been rearing queens in the area for several years, culling their poorest stocks and breeding from their best? Which queen is more likely to raise brood that suits the local environment? Which queen is likely to head a colony with the correct balance of stores and bees to overwinter best? Which queen is more likely, in due course, to yield daughter queens that better suit your local environment, that are placid and exhibit other desirable traits? I have no doubt that a locally raised quality queen would usually be better than an imported queen. However, not all locally raised queens are of good enough quality. This takes us onto the benefits to UK beekeepers of practising sustainable beekeeping.

Capped queen cells

Benefits of sustainable (i.e. no imported bees) beekeeping

If an imported queen cost £500 and package was double that there would be a healthy market for local bees and queens. It would be too expensive to rely on imports to make up for overwintering losses. Beginners would happily wait a week or two or three extra for a locally-raised nuc. What if they were even more expensive than that? What if they were priced beyond the reach of any beekeepers? Or what if imports of any bees were banned entirely? If this were the case there would be real pressure for UK beekeepers to generate sufficient numbers of good quality nucs and queens to meet demands throughout the season. This would involve more beekeepers overwintering nucs to make up losses, to make increase or to sell on in the spring. It would result in more beekeepers learning some of the easy methods of queen rearing (not those involving grafting, mini-nucs or instrumental insemination), so they could become self-sufficient, and would encourage individuals or groups to undertake active stock improvement to raise much better quality queens.

Nucs are more difficult to overwinter than full colonies. But not much more difficult. They have limited space for stores and the winter cluster is smaller. However, high quality poly nucs are now available from a number of suppliers and provide much better insulation to the colony, reducing the rate at which stores are consumed and increasing overwintering success rates. With UK-raised overwintered nucs costing up to £195 in recent years from reputable commercial suppliers the cost of the actual nuc would very soon be recouped even if sold on within the association at a more reasonable cost. If more beekeepers learned how relatively easy it was to prepare and successfully overwinter a couple of nucs it would go some way to meeting the early season demand for bees.

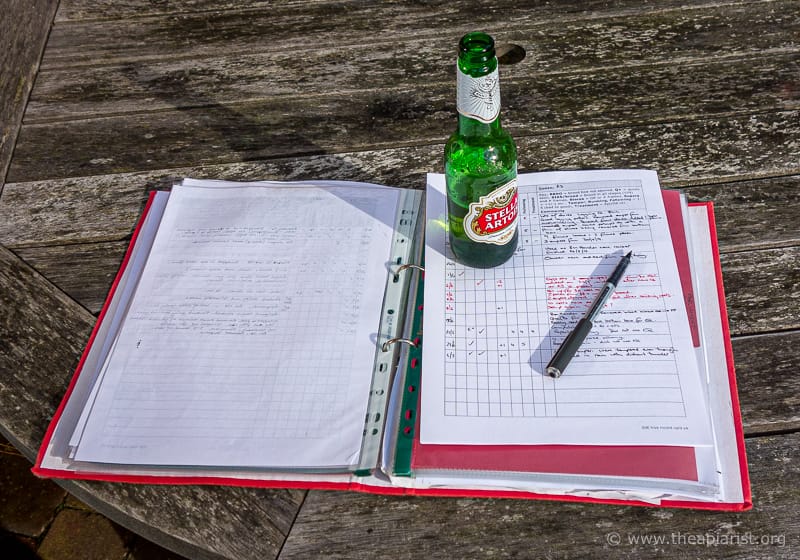

Record keeping …

Most swarm control methods can be readily modified to split a colony, with the queenless ‘half’ raising a new queen in due course. All it requires is a minimum of additional equipment, an appreciation of the timing of the egg-larvae-pupae cycle and the necessary weather and drones for successful queen mating. It also requires reasonable quality bees to avoid propagating unpleasant stock. There’s no point in generating bees that run frantically over the frames, that have a lousy brood pattern, that are aggressive or – my least favourite trait – that follow for hundreds of yards. Any of these take the pleasure out of beekeeping, if combined they are a nightmare (but certainly not unknown). This requires that individuals improve their record keeping, they should improve how they judge their colonies and should then select from their best stock to raise new queens. This doesn’t mean they necessarily have to split (and so weaken) their best colonies … it simply means taking a frame of eggs from their best colony and placing it into a well-populated nuc, then ensuring that queen cells are only raised from the introduced frame of eggs. These small changes in beekeeping practice will enable individual beekeepers to make increase without resorting to imported bees and will – over time – improve both their stocks and their beekeeping.

Tom’s Tables …

Finally, relatively few individual beekeepers keep sufficient numbers of colonies to undertake rational or large scale queen rearing and strain improvement. I certainly don’t. I don’t know how many colonies would be required to start this process off but would suspect it would be at least 50 or perhaps double that number. However, beekeepers with even a handful of colonies can improve their stocks year by year. By routinely selecting from bees with desirable traits for queen rearing and rigorously culling queens with undesirable characteristics – I’ve heard it suggested that the worst 25-30% of stocks should always be requeened – the overall quality of the bees will improve. However, a small group of like-minded beekeepers would easily be managing the 50-100 colonies between them necessary to start more ambitious stock selection. The resources for actually raising queens are relatively limited and could be undertaken in several different apiaries if needed. They would need to agree the quality criteria to judge their colonies against and would need to undertake some joint inspections to decide the desirable lines to keep and the undesirable lines to cull. Groups working together like this already exist, for example several groups work like this in the Native Irish Honey Bee Society.

Conclusions

One of the end products

Beekeeping is not difficult. It’s a hugely engrossing pastime in which the best results are achieved by working with the bees, not against them or by forcing them. Quick fixes, such as importing queens early in the season, reduces the requirement for good bee husbandry and the need to be observant and gradually improve your stock. Although I think that imports should be banned to limit the chances of small hive beetle reaching the UK, I think a far greater benefit of such a ban would be the resulting improvements in the quality of UK beekeeping. These improvements are not achieved by taking more exams or qualifications. They are almost all practical skills, readily acquired by observation, good record keeping, talking with your friends and learning from more experienced beekeepers already practising sustainable beekeeping.

I would like to see national and local associations more actively promoting the benefits of locally-raised bees. These are the organisations that should be coordinating efforts to become less reliant on imported bees, that should be teaching the practical skills necessary for sustainable beekeeping and that will eventually also benefit from improvements in beekeeping in this country.

Additional resources

Readers interested in some of the ideas above should consider attending one of the BIBBA-organized Bee Improvement for All Days this winter. The goal of these workshops is to encourage “beekeepers of all abilities to improve their bees, using simple techniques without the need for specialist equipment“.

Michael Palmer gives a great talk on sustainable beekeeping. You can watch his talk (The Sustainable Apiary) at the 2013 National Honey Show on YouTube or perhaps see him in person at the Somerset Beekeepers 2015 Lecture Day on the 21st of February.

Join the discussion ...