Swarms, lost and found

There is something exhilarating about a swarm.

The chaos and confusion of the whirling maelstrom of bees, corralled and coordinated by a few hundred scout bees, or a hefty dose of pheromones, is a sight to behold.

Whether the swarm is purposefully approaching your bait hive, simply drifting overhead, or disappearing over the apiary fence (for who knows where?) it is undoubtedly one of the greatest sights in beekeeping, as well as being a really fascinating example of animal behaviour.

Of course, just how exhilarating depends upon whether they are your bees, or someone else's ... 😉.

Whatever ... a swarm is still a marvellous spectacle, and one you are bound to see if you spend enough time loitering in apiaries.

If the weather is good enough

2024 is turning out to be a really memorable beekeeping season ... for all the wrong reasons.

I've spent more time ankle-deep in flooded apiaries, wearing a soggy beesuit over a damp fleece, or sitting dejectedly in the car as the rain comes down like stair rods, than any season I remember.

And that's not because my weekly inspection regime has coincided with the only two days of poor weather a week. It's been a shocker for months. Earth might have just experienced the warmest June on record, but it has not felt like that.

The combination of rain and low temperatures has played havoc with honey yields.

Our crop to date is dead zero. We have never had a zero at this stage since my father started in 1950.

— Murray McGregor (@calluna4u) July 8, 2024

Memorable, and for all the wrong reasons

Mine are well down on last year (a good season), but probably about average, and the supers are already filling again. The next 3-4 weeks will be 'make or break' for the summer honey, though the lime already looks like it's going to be a washout 😢.

Queen mating and - more particularly - swarming

But, more significantly, queen mating - and the related activity of swarming - have been seriously impacted by the consistently poor weather.

I discussed aspects of this at length in The year without summer. Don't worry, I'm not going to spend the next 2,500 words whingeing on about the lousy weather and all my unmated queens.

Instead, I'm going to specifically discuss two swarms, both of which either taught me something, or reinforced something I already knew (but had forgotten).

These aren't the only swarms I've seen this year, but there have been so few I need to pace myself to keep some back for future posts.

Fit and forget

I moved some hives to a shared association apiary in late April. On the basis that 'where there are bees, there are swarms' I usually place a bait hive out near(ish) to my apiaries.

I've written exhaustively extensively about bait hives in previous posts so, in the interests of brevity, suggest you check the back-catalogue for all the gory details.

Suffice to say, a bait hive is a hive that, although it contains no bait (!), is attractive to swarms as it offers many of the features that swarms look for when selecting a new nest site.

More specifically, it is attractive to the scout bees that are responsible for finding, judging and choosing the new nest site for a swarm, and for subsequently leading the swarm there.

These desirable features include - some or all of - the volume of the box, its orientation, altitude, entrance size and location, visibility and smell.

I've used bait hives for years and been relatively successful with them. I'm confident that they work. Bait hives are a good example of passive bekeeping, but that's a good thing because they work at the time of the season you are likely to be busiest.

I don't necessarily want the bees they attract, and I certainly don't need them, but if they arrive in my bait hive they don't end up ...

- in the church tower

- or the soffit space over the children's nursery entrance

- frightening 'civilians', or

- dead (the most likely outcome; {{1}}).

So, on a dull afternoon in late April, I assembled a bait hive from two poorly-designed poly supers, an old dark brood frame, a few foundationless frames, a home-made Correx floor and one of the 23 spare roofs (!) I seem to own.

I placed the bait hive in the field margin, near some recently planted saplings, in the lee of a sycamore tree. It was about 30 metres from the hives and reasonably visible ... 'ready and waiting'.

Good things come to those who wait

Periodically, on my weekly apiary visits, I'd check the bait hive. There was no need to open it - the weather had been so poor there had been almost no swarming - but I'd always have a quick peek at the entrance for any activity.

It gradually got more and more overgrown with herbage. The grass started to hide the entrance, and the sycamore started to hide the hive.

And then, in late May sometime, there were a few bees at the entrance.

Just a few.

On checking the hive it appeared to have been occupied by the smallest cast I'd ever seen. Less than a cupful of bees, and I'm not even sure it qualified as a cast (a swarm with an unmated queen) as I never managed to find a queen in it.

I left it there.

A fortnight later, the bait hive was empty again and even more swamped by the herbage. I did some gardening to clear the grass away from the entrance, but otherwise left it alone.

And then, on a very dull morning on the last Sunday of June, a swarm arrived 😄.

Swarmtastic

It was 11:30 am, muggy and heavily overcast, with rain threatening. The wind was almost non-existent and the temperature was no higher than ~16°C.

I was inspecting my second or third colony of the morning when I suddenly became aware of an increased noise of flying bees.

And, not just noise, there were more bees all around me.

A lot more.

Either rain was imminent and this was the foragers returning en masse, or a colony was swarming.

However, standing back from the hive and looking along the row of adjacent hives, it was clear that this was neither of those things.

There were bees everywhere, but no more entrance activity than usual - either arriving or leaving. In fact, the largest concentration of flying bees (where 'concentration' is definitely the wrong word to describe their diffuse distribution) was 10-15 metres in front of me, well away from the hives ... but getting closer.

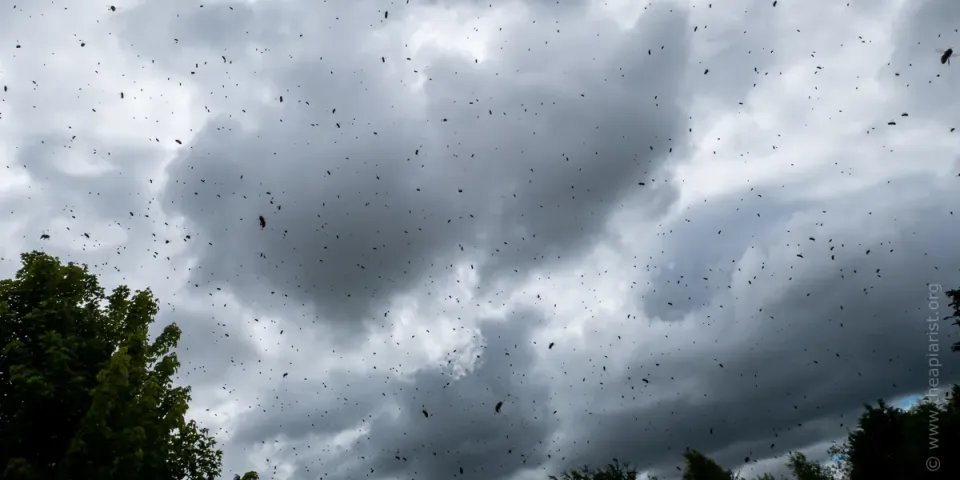

The photo at the top of the page was the swarm as it passed over and around me by the open hives.

I stood spellbound as the swarm engulfed me, then moved slowly past, the numbers thinning from thousands, to hundreds to just dozens all around. They were clearly making for the bait hive behind me, now largely hidden in the overgrown field margin.

'WobbleVision' video of swarm approaching a bait hive

On checking the bait hive entrance (at 11:33) there were only a dozen or so bees around it. Six minutes later there were hundreds of bees on the front of the hive and, after another 15 minutes (11:53), the entrance was completely swamped with bees. Over the next 15-20 minutes the majority of the bees moved inside. By 12:30 - an hour since the swarm first appeared - the hive entrance was quiet again.

11:34, 11:39, 11:53 and 12:29 ... apologies for the bee photobombing the second pic.

During this period, individual bees settled in the grass, on the weeds, bushes and trees, seemingly recuperating from their flight, before taking off again and moving to the concentrated bees at the bait hive entrance.

By the following day the swarm had drawn a frame or so of fresh comb, and they were collected by a bee-less and grateful association member.

Where did they come from?

Swarms tend to move rather short distances from their original nest site. Although they can move several kilometres, most scientific research shows they move at least 100 but generally no more than 400 metres, though one study indicate they may move as little as 20 metres {{2}}.

However, it's worth remembering that these studies tend to be based upon the interpretation of the scout bee dance communication on the surface of a bivouacked swarm.

There are two potential problems with this; firstly, the dance may not be accurately interpreted (I've discussed some of the vagaries of the waggle dance previously) and is rarely confirmed - at least for the more distant sites - by actually locating the new nest site and then measuring the distance moved.

Secondly, the environment may have an uneven distribution of natural nest sites, each of varying 'attractiveness'.

In fact, it's bound to.

Perhaps a swarm moves further for a better nest site (this is inferred, but did they find every closer site?), or chooses the most distant nest site of two equally attractive locations (to reduce competition for resources) ... or, conversely, chooses the closest of two equally attractive sites to facilitate subsequent robbing of the genetically-related colony it originated from?

I'm not sure which (if any) of these are correct.

Bivouacked swarms

When a colony swarms, it generally bivouacs for hours (or potentially days) within a few tens of metres of the original nest site. Over the years, when I've seen my own colonies swarm {{3}} these bivouacked colonies have always been 5 - 30 metres from the original hive.

I do know that this swarm hadn't come from any of my hives (and checked to confirm) but, since I didn't see the bivouacked swarm I'm not sure whether it originated from another apiary, or were from an adjacent association hive that had spent the night bivouacked nearby.

Whichever it was - and I'll never know - it's likely that the colony had probably swarmed 2-3 days earlier. The preceding days were relatively cool with some rain, conditions rarely conducive for swarming.

The lesson here was a reinforcement of something I'm already convinced about.

Bait hives work.

If you provide what the scout bees are looking for - remembering that this is not an absolute list, some flexibility is allowed - then you should attract a swarm. Whether you do or not depends upon local swarming activity, the density of colonies in the area and the number (and quality) of other potential nest sites.

Have confidence, bait hives work.

Win some, lose some

A week later I was back in the apiary, sheltering in the car as the rain hammered down. Although parts of the sky were blue, there were huge, slow-moving clouds laden with rain.

If you were unfortunate enough to be underneath one of these then it was very wet indeed.

Not great for an association 'demo day', though we attempted to inspect some colonies in the gloom under a gazebo. Also, not conditions in which I'd expect to see colonies swarm.

In fact, I'd expect any colonies intent on swarming to delay leaving until the weather improved.

What a difference a day makes - slow moving heavy rain and a balmy day 24 hours later

Which it did the following day.

Blue skies, sunshine, light winds ... and by 3 pm when I arrived at my apiary it was touching 22°C.

Perfect conditions ... for foraging, inspections ... and swarming.

The landowner came over to chat and, since I'd already spent several hours opening hives, I welcomed the chance of a break. As we discussed the poor weather the day before, and the terrible forecast for the following couple of days, I spotted - over the ridge of his workshop - the characteristic spiralling mass of a swarm of bees heading vaguely towards a tall cypress nearby.

Damn!

This was a big swarm. I'd not seen it leave a hive and I couldn't tell from the hive entrances which of them had swarmed, but there was no doubt it was one of mine.

There was nothing I could do about the swarm. It was bivouacked many metres up in the outer branches of a large cypress. The ground below was heavily overgrown and boggy in places:

- even if there had been something to lean a ladder against, there was nowhere safe to stand it on, and

- I couldn't try the - always spectacular but wildly ineffective - trick of throwing a rope over the branch and dislodging the swarm so that it falls onto a large sheet carefully laid out below it (with a strategically positioned hive into which the bees subsequently march).

Why do swarms bivouac?

Swarms do not always bivouac after leaving their original nest site. I think this is reported in some of the early studies by Martin Landauer, but was confirmed to me by Thomas Seeley {{4}}.

However, most swarms do bivouac, and then subsequently relocate to a new nest site which has been found and selected by the scout bees.

Why bivouac? The swarm (I described above) that arrived in my bait hive had undoubtedly spent at least one, and probably 2-3 days and nights out in the open. In that case the weather was mediocre at best, but prolonged periods of heavy rain and cold would threaten their survival.

Surely bivouacking is a risky business?

I can think of two reasons to bivouac:

- to provide the time and space (or more time and space) for the scout bees to conclude their deliberations on the choice of nest site to which the swarm relocates. The evidence that some swarms do not bivouac indicates that scout bees can communicate within the hive (how else would they know where to go?). However, it seems reasonable to expect that separating the waggle dances of returning foragers and scout bees would improve this communication {{5}}.

- to confirm that the queen can fly strongly enough to reach the new nest site. This is a form of 'quality control'. A swarm without a queen is doomed. Individual bees in the swarm, or the few hundred scouts leading the swarm, are unlikely to be able to directly determine the presence (and flying ability) of the queen. Therefore, the queen settles a few tens of metres from the original nest site and the bees join her. Her presence confirms her fitness. The swarm is then quorate ... queen, the workers who left the hive and settled and the scout bees who will lead the swarm onwards.

I presume that the bivouac 'assembles' due to the attraction of the flying workers to pheromones produced by the queen. I cannot image a simple explanation involving the activity of the scout bees who - after all - cannot control where the queen settles. Therefore, an additional 'quality control' role for the bivouac would be to ensure that the queen produces sufficient (or the correct, or correct proportions of) pheromones, again to confirm her fitness.

Why did I lose the swarm?

Formally, I don't yet know whether I've lost it 😉.

More in hope than expectation I placed a bait hive on a relatively dry piece of ground near the base of the cypress. I fully expect this to be studiously ignored and for the swarm to disappear within a day or two.

But that's not why I lost the swarm ... I lost the swarm due to a combination of the weather and (mainly) because I didn't take my own advice 🙄.

There are half a dozen hives in this apiary, and the same number of nucs. The swarm was far too big to have come from a nuc, and most of these have unmated queens anyway 😞. Of the hives, four had new(ish) queens, so were unlikely to swarm, one was requeening and one had a 2022 queen, which my notes indicated was clipped {{6}}.

I suspected I'd previously missed a queen cell or two in this last hive, it had attempted to swarm, lost the mated queen and then swarmed on the virgin.

But I was wrong.

Upon inspecting the hive, I found the clipped and marked 2022 queen calmly walking around the first frame I pulled from the box, and there were no queen cells in the hive.

Instead, it was the box that was requeening that had swarmed.

Don't do this at home (or, for that matter, in the apiary)

The clipped queen had previously been lost in a failed attempt to swarm. I'd then gone through the box carefully and removed all but two queen cells, marking those frames with two white dots, before leaving them to requeen.

Why two cells?

Stupidity.

It was raining. I'll be honest, my thinking was a little confused. I'd found two reasonable cells of different ages; one open and charged, the other a day or two older and sealed. One looked OK, the other was a bit too close to the bottom bar for comfort (but who am I to judge?!). I reasoned that the older queen would emerge first, slay the other and - after the usual interminable wait - get mated and start laying.

However, on opening the box on the day the swarm flew off to the cypress I found - again on the first frame {{7}} - a recently emerged (hours at most, probably less), pale, piping virgin queen. Their behaviour is unmistakeable. She was within a few centimetres of the open cell next to the bottom bar of the frame.

The other cell was also vacant ... but there was no sign of the queen (unless I'd used binoculars to scan the bivouacked swarm 😧).

It seems pretty clear that the first queen emerged and either failed to find, failed to slaughter or - more likely - was prevented from slaughtering the second queen.

I suspect that the workers protected the second queen, probably by holding her in the cell.

After a couple of days of poor weather, the colony swarmed on the first good day, simultaneously releasing the second virgin that I found piping.

The lesson here is clear.

Trust the bees.

They choose the egg/larva to rear as a queen (or several eggs/larvae). Their continued survival depends upon them making the right choices, so there's every reason to expect that any queen cell they generate will produce a perfectly acceptable queen.

Leave just one cell ... any more than that and the colony may swarm.

Mea culpa!

Sponsorship

If you found this, or other posts, amusing, insightful or helpful, then please consider becoming a sponsor of The Apiarist. It costs less than £1/week and ensures you receive every newsletter, including the monthly Bees in the News which should be finished next week, or the recent post on whether labelling your honey as 'raw' is legal - which are only available to sponsors.

Too much of a commitment? Alternatively, you can rehydrate me and simultaneously fix my caffeine dependency (an essential component of my late-night writing) ... and please spread the word to encourage others to subscribe.

Thank you

{{1}}: ~80% of swarms perish from disease or starvation.

{{2}}: These distances apply to classic reproductive swarming by Apis mellifera, not to seasonal or migratory swarming by mellifera or other Apis species which can occur over much greater distances

{{3}}: Yes, it has been known to happen 😄.

{{4}}: Those of you who haven't read Seeley's book 'Honeybee Democracy' should ... it describes the events leading up to swarming, the role of scout bees and the process of nest site selection.

{{5}}: Though possibly unnecessary ... we know that dancing bees can communicate both distance, direction and information about the quality and type of forage, so there's every reason to think they could have an additional 'category' of information on nest sites. Or, for that matter, the scout bees could dance in a different part of the comb.

{{6}}: My notes have been known to be wrong ... perhaps she'd been superseded last autumn, and not seen this year.

{{7}}: More luck than judgement, though I'll claim otherwise.

Join the discussion ...