Queen cells ... quantity and quality

How many queen cells should I leave in my hive?

This question pops up year after year at this time of the season.

Up and down the country we’re all busy implementing swarm control because our swarm prevention, er, didn’t ?

The majority of swarm control methods leave part of the colony to rear a new queen. Once she has emerged, matured, mated and proved her worth by laying up a frame or two you can then decide what to do with the old queen.

Irrespective of the swarm control method you use – e.g. Pagden, nucleus method or a vertical split – the colony often produces quite a few queen cells.

Similarly, if both your swarm prevention and swarm control failed and a prime swarm disappeared over the fence, there are likely to be several (or possibly lots of) queen cells left in the colony.

Queen cells – the good, the bad and the ugly

How many of these queen cells should you leave in the hive?

Which one(s) should you leave?

Assumptions

I’m in the middle of my own swarm control at the moment and so intend to keep this relatively short and simple {{1}}.

I am going to assume you start with one hive and you want to finish with one hive at the end of the process (i.e. you do not want to make increase). I’ll briefly mention rescuing queenless colonies and stock improvement as it’s relevant.

I’m also going to keep this as generic as possible. It’s not going to depend upon the method of swarm control employed or – with some caveats to be discussed later – whether the colony has naturally swarmed.

Here’s the starting position.

Your hive is making preparations to swarm. You apply a swarm control method that removes the old queen from the original brood box {{2}}. This box therefore contains brood in all stages (BIAS) – eggs, larvae and sealed brood. This brood probably occupies most of the frames in the brood box.

Also in the box are a very large number of adult bees, both workers and drones {{3}}.

And there will probably be one, several or lots of unsealed queen cells {{4}} present as well ?

Why do anything? or What’s the worst thing that could happen?

When a colony swarms naturally about 75% of the adult bees leave with the old queen. This figure is similar whether the colony is large or small.

If you start with a large double brood colony it might contain 60,000 bees. Let’s assume a large swarm leaves as the first queen cells are capped (which is when the swarm usually scarpers).

There are still 15,000 bees and perhaps 15-18 frames of brood, several frames of which are close to emerging. The queen laying rate 3 weeks prior to the swarm was probably 1,000 to 2,000 eggs per day, meaning that number of adult workers are now emerging per day.

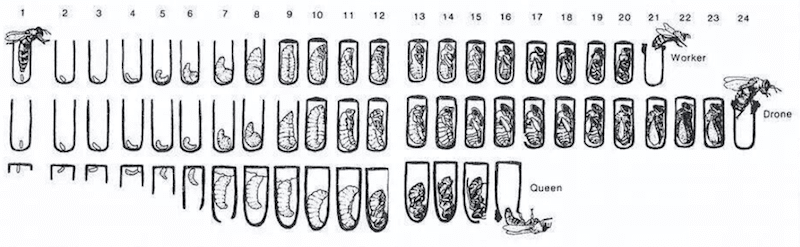

Honey bee development

About eight days after the queen cells were capped and the swarm left the new virgin queens emerge (see the bottom row in the picture above). By this time the worker population in the hive might well be over 20,000 again (some adult worker will have died of old age in the intervening period).

20,000 bees is more than enough to swarm again if several queens emerge {{5}}.

These secondary swarms are called casts. They are headed by a virgin queen. They can be quite large if the original colony was very strong.

However, with a lot of virgin queens emerging around the same time a strong colony can produce several casts, one after another. These are usually successively smaller and smaller {{6}}. Not only are these casts too small to form an effective colony, but the originating colony can be weakened sufficiently to make its survival doubtful.

What’s the alternative?

Imagine the same double-brood colony. The old queen heads for the hills with 75% of the workforce. A week later the colony strength has been boosted by the emergence of a further 7 – 10 thousand workers … but this time there is only one capped queen cell developing.

The queen emerges.

If this queen also disappeared in a cast swarm the original colony would inevitably perish.

Why?

Because a week after the original swarm leaves there are no eggs or larvae in the colony young enough to be reared as new queens.

She’s gone …

Swarming is reproduction of the honey bee ‘superorganism’. The survival of natural swarms is low (~25%) whereas the survival of swarmed colonies is reasonably high (>75%).

From an evolutionary perspective it makes no sense for the only queen to also leave, heading a cast swarm. The colony would have ‘traded’ a ~1:5 chance of producing two viable colonies for a 1:16 chance {{7}}.

It’s a no brainer as they say {{8}}.

So, you can probably see where this is going now …

Swarm control

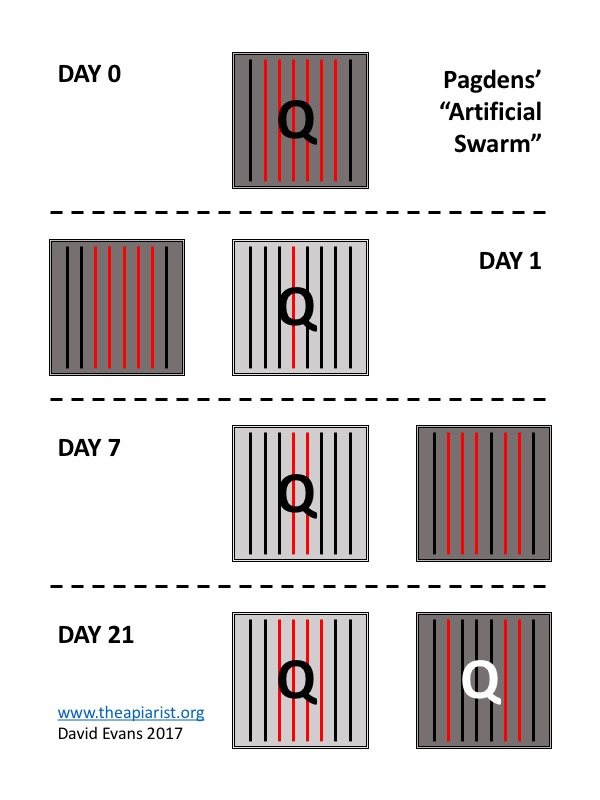

The three relatively generic and representative swarm control methods – Pagden, a nucleus method or a vertical split – all involve manipulation of the hives one week after the initial intervention.

In the ‘classic’ Pagden method the original hive is moved from one side of the artificial swarm to the other. This has the effect of ‘bleeding off’ some of the workforce, so weakening the hive. The resulting reduced worker population often tear down all but a small number of queen cells. The reduced bee numbers also make the production of casts less likely as the colony is weaker.

Pagdens’ artificial swarm …

In a vertical split the hive is reversed on the stand after 7 days, achieving exactly the same outcome on a much smaller footprint with less equipment ? {{9}}

In both these methods the flying bees that have reoriented to the initial new position of the queenless hive return to find the hive moved. They then enter the nearest hive, which is the queenright component (i.e. the artificial swarm).

I’ll get to the nucleus method in a moment.

Sometimes you will see it recommended that you also check the queenless colony at this one week timepoint to ensure that there are not large numbers of queen cells still present {{10}}. It’s not usually necessary but – assuming you are careful – it does not cause any harm. As I explain below, it can help give you confidence.

If you don’t perform the one week hive manoeuvre you really should check for queen cells and reduce the number present.

In the nucleus method I describe the beekeeper must manage queen cell numbers in the queenless hive. Not doing so almost certainly risks losing multiple casts when the queens emerge together.

How many queen cells should you leave?

The queenless component of your swarm control only needs one queen cell.

Any less than that and the colony will be non-viable without further intervention from the beekeeper.

Any more and there’s a risk that the colony will generate one or more casts.

A very strong queenless colony with large numbers of queen cells is a recipe for disaster … or, if not a disaster, then a lot of frustration as you scurry around trying to catch the casts and/or rescue the colony from swarming itself to destruction.

Workers in very strong colonies can ‘hold back’ queens, effectively trapping them in the cell, so that emergence is more-or-less simultaneous. Should you chance to open a colony in this situation all hell breaks loose, with virgin queens dashing about all over the place.

Been there, got the T-shirt ?

Although entertaining – at least is retrospect – it’s better to avoid this sort of situation by restricting queen cell numbers.

All your eggs in one basket

And this is where the beginner starts to experience some trepidation.

They have to reduce queen cell numbers … to one.

That queen will head the colony for the next year or three. She’ll mother tens of thousands of workers who will make countless foraging trips and collect tens or (hopefully) hundreds of pounds of honey.

Choosing that one queen cell feels like a lot of responsibility.

The consequences of choosing a dud feel very serious indeed.

Surely leaving two or three would be a ‘safer’ bet?

Backups, if you will … just in case the first one turns out to be a dud.

How do you know which one to pick?

Trust the bees

And this is where you need to trust the bees. They’ve been doing this pretty well for several million years.

You don’t need to choose a single egg from the thousands possibly present in the colony. The one egg that will be cared for, fed copious amounts of royal jelly and eventually emerge to head the colony.

The bees have already made those decisions {{11}}.

They’ve started several queen cells, the majority of which are likely to be suitable. You just need to choose one of those queen cells to leave in the hive.

It’s not a one in thousands chance of choosing a ‘winner’, it’s more like one in ten … in which any of the ten would probably be OK.

With a few caveats …

What are the features of a good queen cell?

You open the hive and find a number of sealed and unsealed queen cells.

Which to choose?

What are the features you are looking for?

What are the features you can see?

Sealed queen cell …

Size, shape and appearance are the obvious ones. Position on the comb might also influence your choice.

What are the features you cannot see?

Is is a charged cell i.e. does it contain a developing pupa? Has that pupa been well fed as a larva?

Size, shape, appearance and position

Mature queen cells are large, about 3 cm long. The position on the comb – whether on the face or edge can influence the apparent size. They are generally conical, more or less evenly tapering to a neatly rounded tip. Queen cells that have been well-tended by the bees are often heavily sculpted on the outside. This is generally taken to be a “good thing”, but note that this doesn’t happen until after the queen cell is capped (see the photo above). Uncapped cells are usually smooth (see the next photo).

I think the position on the frame is irrelevant in terms of queen cell quality, but it does influence which I choose. The cell should be drawn from worker comb (!) {{12}} and – particularly if I’m likely to be either cutting the cell out or moving the entire frame – I like it to be in a position unlikely to get damaged as I manipulate the frames in the hive.

The edge of drawn comb, with space below and to the side, makes things easy. The central face of the comb, especially if it’s on fresh comb and not near a wire in the foundation, is also a good bet.

The position is more important if you’re going to do something with the cell or frame other than let it emerge in situ.

Charged cells

How do you know there’s a well-fed pupa in the cell?

Ted Hooper (in his Guide to Bees and Honey) describes gently prising the cap off a sealed queen cell to check it is occupied, then re-sealing it to let development run its course. He finishes discussing how to re-seal the cell with the words “you have to do a good job or the bees will tear it down.”

I bet ?

There are easier ways.

Firstly you can be pretty sure that any well-shaped sealed cell with a good, well sculpted appearance is likely to be occupied. Alternatively, you can identify these cells in advance and only allow those you know contain a developing larva sitting on a thick bed of royal jelly to mature.

A practical example

A few days ago I used the nucleus method for swarm control in all my colonies in one apiary. Due to work constraints and lockdown some colonies were only just starting to make preparations to swarm. None of the colonies had well developed, charged queen cells. Some had ‘play cups’ with eggs present.

Three days after making up the nucs I checked the queenless parent colonies. All had a few developing queen cells.

Here is the same photograph as above, with some cells numbered on the frame.

Queen cells – capped, open and just plain dodgy

Which do you choose?

Here is the view from below of the same frame.

Queen cells – practical example

- A sealed cell, perhaps a bit small {{13}}.

- Is a nice looking unsealed cell with a thick bed of royal jelly supporting a larva inside.

- Also unsealed and with a good space underneath for the cell to be drawn out as it develops.

- Is very similar to #2. Smooth exterior as it’s only 3 days old and unsealed.

- A thickened play cup from a previous season. There is no egg, larva or royal jelly inside it.

Remember that this is only 3 days after implementing swarm control.

I destroyed the sealed cell #1. Since it was already sealed it was probably made from an older larva. Cells are sealed on the eighth day after the egg is laid. Since this was only 72 hours after removing the queen the larva was probably two days old before being reared as a queen – i.e. 8 minus 3 days since queen removal minus the three days it would have already spent as an egg. Alternatively, it might have been present when I removed the queen, though I did check reasonably thoroughly.

I couldn’t be sure of the contents of this cell and I suspected that it may not have been fed on copious amounts of royal jelly during the very early days after hatching from the egg.

Cell #3 was also squidged. If you look closely from below you can clearly see the larva but no thick bed of royal jelly. I doubted it had been fed well enough in the early days. Here’s an enlargement …

Cells #1 to #4 enlarged.

Why risk it? There are better cells on the frame.

I ignored #5. It’s not a queen cell and never will be.

Uncapped cells #2 and #4 were retained. They are the right size, have a good appearance and are well placed on the frame.

I marked the top of the frame with a queen marking pen to remind me where to check, and more importantly where to be careful, when I inspect the colony a week after making up the nuc.

X marks the spot

Note that the photo above is a different hive to the numbered photo of queen cells (which I forgot to photograph).

Hold on … not so fast

Go back and look again at the numbered photo of queen cells.

There is another cell, uncapped and filled with royal jelly, to the left and a little higher than the sealed queen cell #1.

This cell is actually pretty obvious. There are relatively few bees on the frame and it is not particularly well ‘hidden’.

Miss a couple more like that in a very strong hive and there’s a chance the colony will throw off several casts when the queen emerge. The unlabelled cell, and cells #2 and #4 are all very similar in age and appearance and would likely emerge within hours of each other.

Seven days after implementing swarm control

The hives are checked again {{14}}.

I know which frames have good, charged developing queen cells. They are the ones that are marked. I therefore :

- treat these frames very carefully. Do not shake the bees off the frame!

- make sure the cells are now capped and starting to be sculpted by the bees.

- gently inspect the remainder of the frame for other queen cells.

- destroy any new cells that I find

I choose one of the queen cells and destroy any others on the frame. If there is more than one marked frame and I don’t need the cell for another colony (see below) then I destroy the cells on the other marked frame as well.

I then thoroughly inspect every frame in the brood box, shaking all the bees off the frames and checking for any queen cells I may have missed previously. There will be some.

All I find are destroyed.

I close the hive up and leave it undisturbed for the queen to emerge, mate and start laying. I’ll discuss this – apparently interminable – period in the future sometime.

I’m confident the cell contains a well fed pupae. It was the the bees that really selected the queen … all I did was whittle down their selection to the final choice.

Using ‘spare’ queen cells

In the photo above there are two marked frames. This is a good colony. Frugal, productive, well behaved etc. {{15}}

There is another colony in the apiary which is poorly tempered. They are also requeening and are at the same stage.

Assuming the cells on both marked frames are good I’ll transfer one to the badly behaved colony when I conduct the seven day inspection. You can transfer the entire frame or you can gently cut the queen cell out and use it directly {{16}}

All of the developing queen cells in the badly behaved colony will first be destroyed. Since there are no eggs or young larvae in that colony (and no queen as she was removed a week ago) they cannot rear another from their own genetic material.

The new queen will be better quality.

Similarly, you can use a ‘spare’ queen from a good hive to rescue a terminally queenless colony, or to replace an underperforming or substandard queen.

A really dodgy queen cell

I wanted to squeeze in a picture of what not to choose.

Bride of Frankenstein queen cell

There are so many things wrong with this.

Where to start?

It’s drawn from drone comb and is not neatly tapering and conical. It’s poorly sculpted considering its age and size, which is far too big.

Whatever emerges from this cell, if anything, will not be any use to me or the bees ?

Seven day only inspection

The process described above involves an additional inspection 3-4 days after implementing swarm control. I think this is a modest amount of additional work for:

- the peace of mind it gives when selecting the final cell to leave

- the time saved when going through the colony at the seven day inspection

However, often it’s not possible. In that case I refer you back to the description of what a good sealed queen cell looks like.

Choose one of those.

Just one ?

Notes

With gale force winds predicted for the next 2-3 days I ended up checking the ‘example’ colony (above) on day 6 after implementing swarm control measures. Here is the same frame:

Just one!

I removed two less convincing queen cells on either side of the one selected (#2 in the labelled photograph further up the page). There were a small number of queen cells elsewhere in the colony. All were removed. I’m leaving just one cell sealed, I know it contains a well fed larva. She’ll emerge in about a week and should be mated – weather permitting – a week or so after that.

And now the wait begins … ?

{{1}}: Ha! Famous last words … remind me of this in 2400 words time.

{{2}}: Any of the three methods mentioned earlier – Pagden, a nucleus method or a vertical split – fit this general description.

{{3}}: It’s very unusual for a colony to swarm without already containing a good number of drones.

{{4}}: There are unlikely to be sealed queen cells as the colony would probably have already swarmed.

{{5}}: Why they do this is an interesting point as it probably generates casts with a very low potential to survive.

{{6}}: Some can be as small as an orange.

{{7}}: Reciprocal of 0.75 x 0.25 vs. reciprocal of 0.252. In reality, cast survival is appreciably lower than prime swarm survival for two reasons – size and the need to get the virgin queen mated.

{{8}}: The argument here is slightly artificial as I’m mixing feral/wild colony survival rates with managed colony sizes. In reality wild colonies may never get to be anything like as big and strong as managed colonies. If they did they might generate several casts. Some do. Nevertheless, they would not evolve a mechanism that was inherently more risky than one in which the original colony probably survived. Our managed colonies’ behaviour results from millions of years of evolution as wild honey bees.

{{9}}: And much more heavy lifting.

{{10}}: There shouldn’t be if you have performed the manipulations in the right way.

{{11}}: Read my previous post Who’s the daddy? about egg selection under the emergency response … the workers are very selective about which eggs they choose.

{{12}}: A male larva will not develop into a very good queen.

{{13}}: Always more deceptive on the face of the comb as the cell goes some way into the comb as well.

{{14}}: I’m doing this the day this post appears online, so am unlikely to be able to update the photographs.

{{15}}: If you’re reading this and are in the market for a nuc then, of course, all my bees are like this … the tetchy colony described below belongs to a ‘friend’.

{{16}}: 2903 words already … I have no time to describe this, I will in the future.

Join the discussion ...