Winter bee production

There are big changes going on in your colonies at the moment.

The summer foragers that have been working tirelessly over the last few weeks are slowly but surely being replaced. As they die off – whether from old age or by being eaten by the last of the migrating swallows – they are being replaced by the winter bees.

Between August and late November almost the entire population of bees will have changed. The strong colonies you have now (or should have) will contain a totally different workforce by the end of the year.

Forever young

The winter bees are the ones responsible for getting the colony from mid/late autumn through to the following spring. They are sometimes termed diutinus bees from the Latin for “long lived”.

These are the bees that thermoregulate the winter cluster, protecting the queen, and rearing the small amounts of brood during the cold, dark winter to keep the colony ticking over.

Physiologically they share some striking similarities with so-called hive or nurse bees {{1}} early in the summer.

Both hive bees and winter bees have low levels of juvenile hormone (JH) and active hypopharyngeal glands. Both types of bee also have high levels of vitellogenin, high oxidative stress resistance and corpulent little bodies.

But early summer nurse bees mature over a 2-3 week period. Their JH levels increase and vitellogenin levels decrease. This induces additional physiological changes which results in the nurse bee changing into a forager. They sally forth, collecting nectar, pollen and water …

And about three weeks later they’re worn out and die.

And this is where winter bees differ. They don’t age.

Or, more accurately, they age v e r y s l o w l y.

In the hive, winter bees can live for 6 months if needed. Under laboratory conditions they have been recorded as living for up to 9 months.

They effectively stay, as Bob Dylan mumbled, forever young.

Why are winter bees important?

Although not quite eternal youth … staying forever young is useful as their longevity ensures that the colony does not dwindle and perish in the middle of winter.

With little or no nectar or pollen available in the environment the colony reduces brood rearing, and often stops altogether for a period.

But what about the kilograms of stores and cells filled with pollen in the hive? Why can’t they use that?

Whilst both are present, there’s nothing like enough to maintain the usual rate of brood rearing. If they tried the colony would very quickly starve.

Evolution has a very effective way of selecting against such rash behaviour 🙁

If you doubt this, think how quickly hives get dangerously light during the June gap. With no nectar coming in and thousands of hungry (larval) mouths to feed the colony can easily starve to death during a fortnight of poor weather in June.

The winter bees ‘hold the fort’, protecting the queen and rearing small amounts of brood until the days lengthen and the early season pollen and nectars become available again.

And, just as the winter bees look after the viability of the colony, the beekeeper in turn needs to look after the winter bees … we rely on them to get the colony through to spring.

Can you identify the winter bees?

But before we discuss that, how do you identify and count the winter bees? How can you tell they are present? After all, as the picture above shows {{2}}, all bees look rather similar …

Counting the long lived winter bees

The physiological changes in winter bees, such as the JH and vitellogenin levels, are only identifiable once you’ve done some rather devastating things to the bee. These have the unfortunate side effect of preventing it completing any further bee-type activities 🙁

Even before you subject them to that, their fat little bodies aren’t really sufficiently different to identify them visually.

But what is different is their longevity.

By definition, the diutinus or winter bees are long lived.

Therefore, if you record the date when the bee emerged you can effectively count back and determine how old it is. If it is more than ~6 weeks old then it’s a winter bee.

Or the queen 😉

And, it should be obvious, if you extrapolate back to the time the first long lived bees appear in the hive you will have determined when the colony starts rearing winter bees.

The obvious way to determine the age of a bee is to mark it upon emergence and keep a record of which marks were used when. Some scientists use numbered dots stuck to the thorax, some use combinations of Humbrol-type paint colours.

I’m not aware that anyone has yet used the barcoding system I discussed recently, though it could be used. The winter bee studies I’m aware of pre-date this type of technology.

Actually, some of these studies date back almost 50 years, though the resulting papers were published much more recently.

This is painstaking and mind-numbingly repetitive work and science owes a debt of gratitude to Floyd Harris who conducted many of the studies.

Colony age structure – autumn to winter

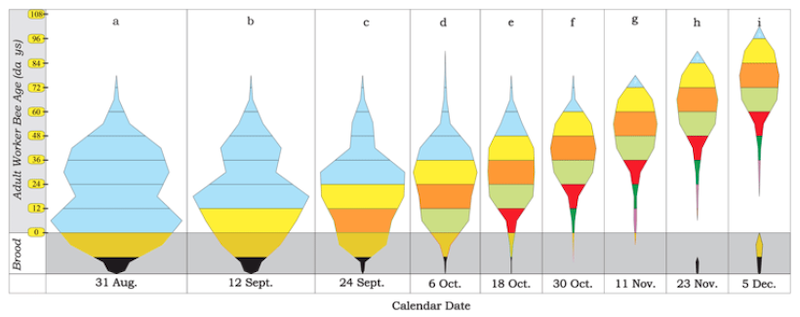

Here is some data showing the age structure of a colony transitioning from late summer into autumn and winter. There’s a lot in this graph so bear with me …

The graph shows the numbers and ages of bees in the colony.

The ages of the bees is indicated on the vertical axis – with eggs and brood (the youngest) at the bottom, coloured black and brown respectively. The adult bees can be aged between 1 and ~100 days old {{3}}. The number of bees is indicated by the width of the coloured bar at each of the nine 12 day intervals shown.

All of the adult bees present in the hive at the end of August are coloured blue, irrespective of their age. There are a lot of these bees at the end of August and almost all of them have disappeared (died) by mid-November {{4}}.

The remaining colours indicate all the bee that emerge within a particular 12 day interval. For example, all the bees that emerge between the 31st of August and the 12th of September are coloured yellow. Going by the width (i.e. the numbers of bees of that age) of the yellow bars it’s clear that half to two-thirds of these bees die by mid October, with the rest just getting older gracefully.

But look at the cohort that emerge between the end of September and early October, coloured like this {{5}}. The number of these bees barely changes between emergence and early December. By this time they are 72 days old i.e. an age that most summer bees never achieve.

Brood breaks and climate

In the colony shown above the queen continued laying reduced numbers of eggs – the black bars – until mid-October and then didn’t start again until the end of November. During this period the average age of the bees in the colony increased from ~36 days to ~72 days and the strength of the colony barely changed.

The figure above comes from a BeeCulture article by Floyd Harris. The original data isn’t directly referenced, but I suspect it comes from studies Harris conducted in the late 70’s in Manitoba, some of which was subsequently published in the Journal of Apicultural Research. In addition, Harris co-authored a paper presenting similar data in a different format in Insectes Sociaux which describes the Manitoban climate as having moderate/hot summers and long, cold winters.

My hives in Scotland, or your hives in Devon, or Denmark or wherever, will experience a different climate {{6}}.

However, if you live in a temperate region the overall pattern will be similar. The summer bees will be replaced during the early autumn by a completely new population of winter bees. These maintain the colony through to the following spring.

The dates will be different and the speed of the transition from one population to the other may differ. The timing of the onset of a brood break is likely to also differ.

However, the population changes will be broadly similar.

And, it should be noted, the dates may differ slightly in Manitoba (and everywhere else) from year to year, depending upon temperature and forage availability.

Colony size and overwintering survival

Regular readers might be thinking back to a couple of posts on colony size and overwintering survival from last year.

One measured colony weight, showing that heavier colonies overwintered better {{7}}. A second discussed the better performance of local bees in a Europe-wide study of overwintering survival. In this, I quoted a key sentence from the discussion:

“colonies of local origin had significantly higher numbers of bees than colonies placed outside their area of origin”

I can’t remember when during the season those studies recorded colony size, but I’m well aware that large colonies in the winter survive better.

The colonies that perish first in the winter are the pathetic grapefruit-sized {{8}} colonies with ageing queens or high pathogen loads.

In contrast, the medicine ball-sized ‘boomers’ go on and on, emerging from the winter strongly and building up rapidly to exploit the early season nectar.

But what the graph above shows is that the bees in a strong colony in late summer are a completely different population from the bees in the colony in midwinter.

The strength of the midwinter colony is determined entirely by when winter bee rearing starts and the laying rate of the queen, although of course both may be indirectly influenced by summer colony strength.

The influence of the queen

Other than this potential indirect influence, it’s possibly irrelevant how large the summer colony is in terms of winter colony size (and hence survival).

After all, even if the summer bees were three times as numerous, their fate is sealed. They are all going to perish six weeks or so after emergence.

Are there ways that beekeepers can influence the size of the overwinter colony to increase its chances of survival?

I wouldn’t pose the question if the answer wasn’t a resounding yes.

It has been known for a long time {{9}} that older queens stop laying earlier in the autumn than younger queens. As explained above, the longer the queen lays into the autumn the more winter bees are going to be produced.

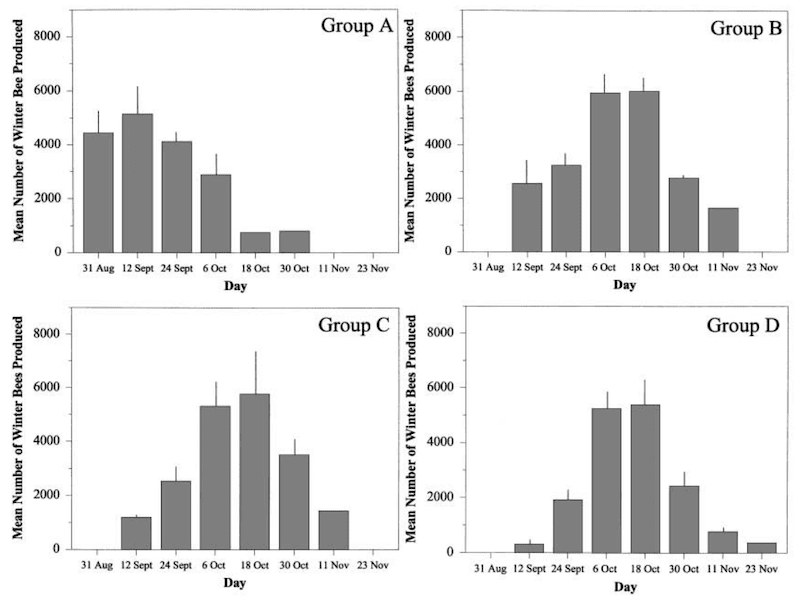

Mattila et al., {{10}} looked at the consequences of late season (post summer honey harvest) requeening of colonies. In these they removed the old queen and replaced her with either a new mated or virgin queen, or allowed the colony to requeen naturally.

Using the ’12 day cohort’ populations explained above, the authors looked at when the majority of the winter bees were produced in the colony, and estimated the overall size of the winter colony.

The influence of new queens on winter bee production. Note shift to the right in B, C and D, with new queens.

With the original old queen, 53% of winter bees were produced in the first two cohorts of winter bees. With the requeened colonies 54-64% of the winter bees were produced on average 36 days later, in the third and fourth cohorts of winter bees.

This indicates that young queens produce winter bees later into the autumn.

This is a good thing™.

In addition, though the results were not statistically significant, there was a trend for colonies headed by new queens to have a larger population of bees overwinter.

Perhaps one reason the requeened colonies weren’t significantly larger was that the new queens delay the onset of winter bee rearing. I’ll return to this at the end.

The influence of deformed wing virus (DWV)

Regular readers will know that this topic has been covered extensively, and possibly exhaustively, elsewhere on this site … so I’ll cut to the chase.

DWV is the most important virus of honey bees. When transmitted by Varroa destructor there is unequivocal evidence that it is associated with overwintering colony losses. The reason DWV causes overwintering losses is that it reduces the longevity of the winter bees.

The virus might also reduce the longevity of summer bees but,

- there’s so many of them to start with

- there’s loads more emerging every day, and

- they only survive a few weeks anyway,

that this is probably irrelevant in terms of colony survival.

Dainat et al., (2012) produced compelling evidence showing that DWV reduces the longevity of winter bees {{11}}. The lifespan was reduced by ~20%.

A consequence of this is that the winter bees die off a little faster and the colony shrinks a little more. At some point it crosses a threshold below which it cannot thermoregulate the cluster properly, further limiting the ability of the colony to rear replacement bees (assuming the queen is able to lay at a low rate).

This colony is doomed.

Even if they stagger through to the longer days of spring they contain too few bees to build up fast. They’re not dead … but they’re hardly flourishing.

Winter bees and practical beekeeping

I think there are three ways in which our understanding of the timing of winter bee production should influence practical beekeeping:

Firstly … The obvious take-home message is that winter bees must be protected from the ravages of DWV. The only way to do this is to minimise the mite population in the colony before the winter bee rearing starts.

The logical way to do this is to treat using an approved miticide as soon as practical after the summer honey is removed {{12}}.

I discuss the importance of the timing of this treatment in When to treat?, which remains one of the most-read posts on this site.

Secondly … Avoid use of miticides (or other colony manipulations) that reduce the laying rate of the queen in early autumn.

When I used to live at lower latitudes I would sometimes use Apiguard. This thymol-containing miticide is very effective if used when the temperature is high enough. However, in my experience a significant proportion of queens stop laying when it is being used. Not all, but certainly more than 50%.

I don’t know why some stop and others don’t. Is it genetic? Temperature-dependent?

Whatever the reason, they stop at exactly the time of the season you want them to be laying strongly.

Thirdly … consider requeening colonies with young queens after the summer honey is removed. This delays the onset of winter bee production and results in the new queen laying later into the year. The later start to winter bee production gives more time for miticides to work.

A win-win situation.

{{1}}: i.e. bees that stay in the hive and have yet to develop foraging activity.

{{2}}: And you’re probably already aware as this is a site for beekeepers!

{{3}}: Data collection stopped at this point … if it had continued, the bees would have been shown to live longer.

{{4}}: The few shown as remaining may be a graphing artifact. Numerically they’re a tiny component and we can safely ignore them.

{{5}}: I’m colourblind, so can match the colour digitally, but can’t name it!

{{6}}: Unless you live in Manitoba, and about 3% of the readership of this site are from Canada, so it might be rather similar for you.

{{7}}: But there was also a relationship with colony size – large colonies collect more nectar and so weigh more.

{{8}}: Or smaller.

{{9}}: For example, Cale, G.H. (1956) In The Pink For Winter. American Bee Journal. 96:397 – 400.

{{11}}: See also van Dooremalen C et al. (2012) Winter Survival of Individual Honey Bees and Honey Bee Colonies Depends on Level of Varroa destructor Infestation. PLoS ONE 7: e36285.

{{12}}: There may be other ways to do this but I’ve seen no compelling evidence that other methods are at least as efficient and have as little detrimental effect on the bees.

Join the discussion ...