And then there were three

If you've arrived here looking for an insightful review of the first studio album after Steve Hackett left the 1970s prog rock band Genesis, then you're (probably) going to be disappointed. “And then there were three” was a financial success, but long-time fans considered Genesis had sold out to commercial pop pressure. The catchy but vapid single “Follow you, follow me” was most notable for predicting social media activity by decades.

I considered other titles; “Three's a crowd” (with cultural references to a poor TV sitcom), “Three-ring circus” (possibly more accurate as it can mean 'a state of confusion') or “Three sheets to the wind” (interesting etymology, but not appropriate … bees and booze don't mix), but got distracted listening to The lamb lies down on Broadway, so here we are.

Stuff has been happening in three's over the last fortnight. Queens, swarms and more queens. Since they are all tangentially related I've woven them together into a single post.

Three queens

Last season was a shocker as far as my queen rearing went. Between May and early July I was busy preparing to move house and the weather was awful. In late summer, other than a fortnight of balmy weather at the start of August (and a monumental nectar flow 😄), it was just cold or wet.

Except for when it was cold and wet.

My Fife queen rearing never really got started and my West Coast bees were left to their own devices as I repeatedly drove a van back and forth to the Scottish Borders.

In the absence of good conditions earlier in the season, many colonies superseded (or attempted to) in late August or September. This was variably successful, and I had to do some late season uniting in October to avoid losing colonies overwinter {{1}}.

But that wasn't the end of the problems.

Some colonies, containing queens mated poorly in 2024 or older queens that hadn't been superseded, took advantage of the excellent weather in late April this year and tried to “do better next time”.

Typically, this involved me finding one or more supersedure cells in the colony.

And this is the tale of one such colony where I found the original queen and one 'supersedure cell' on the 22nd of April …

Don't take queen cell position as evidence of intent

A queen cell located roughly centrally on a frame will often be described as a 'supersedure cell'. However, do not rely upon this diagnosis if there is evidence to the contrary.

For example, in late May with wall-to-wall brood I'd be reaching for a nuc box to apply some swarm control, even if there was only one developing queen cell.

However, my interpretation that the late April queen cell was an attempted supersedure was based upon additional evidence:

- the colony wasn't strong enough to swarm, with no more than 3–4 frames of brood

- there was little capped drone brood and no mature drones (in this colony, or others in the apiary) {{2}}

- there was some evidence that the current queen was failing or below par e.g. an increasingly spotty brood pattern, and signs that the queen was being harried by the workers (nibbled wings, no strong retinue around her)

And finally, the queen (Q33) — marked and clipped in 2022 — was old.

Subscribers to The Apiarist receive regular newsletters on the science, art, and practice of sustainable beekeeping. Why not sign up and join them now?

Watch and learn

Not only did my notes indicate she was aged, but she looked old.

Her wings had been nibbled down to stumps just 3–4 mm long, and she looked very battered and bedraggled.

On the 22nd of April she was still laying, but there was that one obvious supersedure cell and about three and a bit frames of brood. Q33 was a native black bee and my notes indicated she'd always started the season slowly. In the hope of keeping her laying a bit longer {{3}} I moved the colony into a well-insulated nuc box.

At the next inspection on the 2nd of May the cell was opened and there was a new dark virgin queen running about. There was no open brood present and I didn't see Q33.

In my defence, I didn't look too hard. Once I saw the virgin queen I closed the box to avoid disturbing things too much.

On the 10th of May the new queen was no longer scurrying about, but she also wasn't yet laying. Again, it was little more than a cursory check through the box. However, I was pretty sure this queen was mated and would start laying in the next day or two.

Why the confidence? Firstly, she was much calmer, sauntering around the frame with a bit more authority. This behavioural change is often seen after the queen is mated. Secondly, there were 'polished cells' in the centre of what would become the brood nest. This polished appearance is due to the workers cleaning the cell in preparation for the queen laying in them.

Late on the 14th there were almost two frames of freshly-laid eggs. Perhaps I'd missed some on the 10th, or maybe she just started at breakneck speed. Whatever, I closed the box up and let them get on with things, adding a note to my records that they'd need a 'full box soon'.

Successful supersedure 😄 … “Don't you just love it?”

Don't jump to conclusions

On the 23rd the colony was doing well.

I inspected it properly as I transferred frames from the nuc to a full brood box.

I found a small, dark, queen on the first brood frame I pulled, and — assuming she was the laying queen (and why wouldn't I?) — clipped her and marked her white. The laying pattern was good, and the colony was expanding well.

On the second brood frame there was a single, open, charged queen cell i.e. containing a larva on a bed of royal jelly … and a dark, unmarked queen.

Eh?

This queen was fractionally larger than the first, and was also sauntering around reasonably confidently.

Perhaps this was the new laying queen?

I've no idea where she (or the first one) had come from as I'd only found one 'supersedure cell', and there was insufficient time from the first appearance of eggs in the colony for a new queen to have been reared.

Perhaps she was a second supersedure queen (from a cell I'd missed {{4}})?.

But there's another interpretation … perhaps she was a queen originating from a nearby colony that had entered the wrong hive when returning from a mating flight?

However, my other colonies were queenright.

I'll return to this point in a few minutes {{5}}.

I marked this second queen yellow to differentiate her from the first I'd marked white. I don't use the year/colour scheme as I cannot see or differentiate the green/red colours, and am too mean to buy many Posca pens. I mark my queens white, blue, or yellow depending upon which colour pen I can find that works in my bee bag.

And then, on the very last frame I found the original Q33.

Her nibbled wings and remnants of the paint I'd added in late 2022 were unmistakeable. She looked knackered. Barely walking, just hanging in there. I suspect she'll be gone when I check next time.

And that open queen cell?

Sometimes you have to assume that the bees do not know what they're doing.

Whichever queen was laying, they were laying well. Perhaps it was both of them? There were good amounts of sealed and open brood, and lots of space.

No need to swarm and no obvious need to supersede.

I assumed the open queen cell was a simple error of judgement and destroyed it.

Presumptuous perhaps, but things were starting to get silly.

I think three queens in a box is a record for me (excluding those mad times when you open a colony with a dozen or more emerging virgin queens … a transient, but shambolic, situation), and it will be interesting to see which of the three is present next week.

If it's Q33 I'll be amazed.

And the moral of this tale? Don't stop looking when you find what you want.

That's beekeeping advice, not marital advice 😉.

Three swarms

A couple of weeks ago I commented that there were again scout bees around a bait hive in my garden.

Again, because I'd already had two swarms to a bait hive in that location on the 10th and 11th. In each instance I'd moved the occupied bait hive in the evening on the day the swarm arrived, replacing it with another empty — but nevertheless very welcoming 😉 — box in the same spot.

As Friday's post went to press the scout bees were back mob handed and, late on the Saturday afternoon (the 17th, I'd just got back from a queen rearing course), a large swarm drifted in across the field and moved in.

An hour or two later I donned my jacket and veil again, filled the hive with frames and wedged them tightly together with a small block of closed cell foam to prevent any 'shiggling' when being transported by car.

And, later still, I moved them to the apiary.

Three swarms in a week to a single bait hive location is a personal record. Perhaps I should get the divining rods out and look for the ley (energy) lines that Roger Patterson has written and talked about?

A web search turns up all sorts of spiritual nonsense on divining/dowsing; apparently the same divining rods can be used to detect water, oil, gemstones, to communicate with spirits, or 'talk' to ghosts.

While the empirical scientist in me thinks “b***ocks”, I am aware that some bait hive locations are very much more successful than others.

Anyway, that's more than enough about the paranormal for one post, let's get back to those swarms.

Little and large … and large

The first and third swarms were large, which I define as covering at least seven frames with a thick carpet of bees. When adding frames to these swarms, the walls of the hive are an inch or more thick in clinging bees, and the frames must be lowered very gently to avoid crushing or disturbing them too much.

The second swarm was much smaller, and I speculated at the time that it might be from a free-living colony.

Why free-living, rather than just a small swarm from a managed hive? Or perhaps even a cast (a swarm headed by a virgin queen, which always smaller than primary swarms)?

This small swarm (3–4 frames of bees) contained eggs when I checked on the 14th, three days after it arrived. This is almost certainly too little time for a virgin queen to mate and start laying.

In addition, it also had a significantly higher mite load (2-3 times the number dropped within 48 hours of Api-Bioxal treatment) than the first swarm, further supporting evidence that it may have originated from an unmanaged colony.

The third and final swarm was different again … plenty of bees, but I didn't see evidence for a laying queen until 6 days after they arrived, and then there were eggs but no larvae.

This suggests to me that the queen wasn't mated when she arrived, though of course all I'm doing is a 'best guess' interpretation of what I see

Prime swarm or cast … or casts?

But, remember, this final swarm was large … in fact, it probably contained more bees than the first of the three swarms that week. The bait hive — a lightweight poly hive — was noticeably heavy when I relocated it to the apiary.

That seems odd as casts are typically smaller than prime swarms.

Prime swarms contain the mated queen plus up to 75% of the workers. To subsequently generate a cast of the size of this third swarm the parent colony would have had to be huge.

Not impossible, but not likely.

I'll never know of course, but since I'm in 'wild-but-not-entirely-uninformed speculation' mode let's take this one stage further.

Some swarms, and particularly casts, contain more than one queen. This can happen when a single colony produces multiple casts, or when numerous colonies produce casts.

François Huber (way back in 1792 and, subsequently, lots of others) have documented that these casts can coalesce to form very large swarms, containing many queens.

A 'spare' queen

Let's assume that the second large swarm was composed of merged casts.

Typically, the virgins would fight, leaving one survivor to get mated. But this process may take some time (days) when the colony is populous (see the description by Huber above).

If these sporadic skirmishes overlapped with the time the colony was encouraging the queen(s) to get out and mate there could be an opportunity for one queen to 'escape' and — on returning to the apiary — enter an adjacent hive.

For example … a nuc that was in the process of superseding its ancient and failing queen on the adjacent hive stand (see above).

This queen acquisition could occur when she returns from either a mating or an earlier orientation flight. In the latter case she would still be a virgin.

As I said, 'wild-but-not-entirely-uninformed speculation' … but I can't see an obvious alternative source for the third queen in the superseding nuc (if you assume I didn't miss a cell).

As Sherlock Holmes said “… when you have eliminated the impossible, whatever remains, however improbable, must be the truth”.

I've not eliminated the impossible, and what's left is improbable, but it's the best I can come up with.

And the moral of this tale? Try to understand what's happening but be prepared to accept that it sometimes makes no sense at all.

That's beekeeping advice, not marital advice 😉.

Three more queens

My first round of grafting this season was “quick'n'dirty” as I only wanted to test whether larvae presented in 3D printed cell cups — in place of commercial Nicot or Jenter cups — would be accepted and reared as queens.

The weather was poor, cool with a strong gusty wind, my head torch was dud, I'd forgotten my glasses, and had nothing to protect the grafted larvae (like damp tissue) to prevent them from drying out. In addition, I'd taken a friend with me to the apiary to show them the bees, and I was conscious of the time I was taking.

Altogether these were suboptimal conditions for grafting, and very different from the warm, well-lit room with a constantly boiling kettle to maintain a humid atmosphere you sometimes see recommended (but I've never used).

Nevertheless, I persevered, grafting larvae into a variety of cups printed from different filament types. Considering the conditions, to my surprise, 7 of the 10 larvae were accepted, and six were eventually capped to allow pupation to start.

A day or so after capping, the cells were transferred to my portable queen cell incubator to free up the cell raiser for a second round of grafting.

The invariant queen development timetable

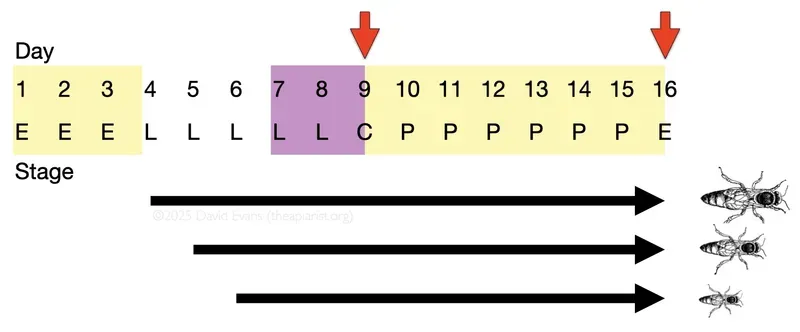

Queens take 16 days to emerge after the egg is laid.

Not 15 or 17; the development cycle is effectively invariant.

The egg hatches on day 3, the larva is capped on day 9, and the adult queen emerges on day 16 {{6}}.

After hatching from the egg, larvae are pluripotent for the first three days only. This means that, during this period, if fed on royal jelly they will become queens.

Don't think of a queen as an absolute definition; some are more queen-like and others are more worker-like, and where they are on the queen-to-worker scale depends upon the duration that they are fed royal jelly.

The more royal jelly they receive, the more queen-like they are {{7}}.

And, generally, the bigger they are {{8}}.

Under the emergency response, the colony prefers to start new queens from 3 day old eggs. This makes perfect sense as it provides the maximum time for feeding royal jelly, so ensuring the biggest and best queen possible.

But when grafting larvae the cell raising colony starts with whatever I can see and pick up with my little paintbrush.

And on an overcast day, with no head torch and no glasses, I was largely working by instinct guesswork, so it's not surprising that some larvae were larger (i.e. older) than others.

The proof of the pudding

Three of the largest cells from the incubator were used to make up nucs.

The sealed cell — two days before emergence — was added to a box containing a frame of emerging brood, plus the bees from one or two additional frames, together with a frame of stores. In a fortnight these should contain mated queens.

The remaining three cells were incubated until emergence.

The larvae were grafted on the 11th, so emergence was expected on the 23rd assuming I'd managed to pick 12-24 hour old larva. Any that emerged prior to the 23rd — on account of the invariant queen development cycle — must have been older than 24 hours.

A queen emerged from the smallest cell in the incubator at breakfast time on the 22nd. This larva must have been approaching 48 hours when grafted i.e. too old. A second queen emerged late on the 22nd (again too old), and the final one emerged on the morning of the 23rd.

The third queen (and cell) was the largest, as would be expected from the additional time feeding on royal jelly.

In the incubator, new queens can be maintained on a diet of dilute honey for a few days after emergence. I just give them a small drop morning and evening, onto the inner lid of the hair roller cage. I also remove the empty queen cell to prevent the queen re-entering it and getting stuck.

Alternatively, they can be 'banked' in queenless colonies, but that needs more resources than I can justify.

Requeening a swarm … or not

The downturn in the weather over the last few days has amplified any unpleasant traits colonies have. The first large swarm, although not too 'hot' to handle, weren't pleasant, so I decided to requeen them with the largest 'spare' queen from the incubator.

This is usually routine. I go through the colony, find and dispatch the original queen, wait 24 hours, then introduce the new queen in a sealed cage. I subsequently release her — by removing the plastic cap and allowing the colony to munch through a plug of queen candy — once the colony shows no aggression to the caged queen.

Unfortunately, the afternoon I set out to do this was far from suitable. There were 40+ mph Westerlies bringing frequent bands of heavy rain in, interspersed with bright sunshine.

Unsuitable, but that doesn't mean I didn't try 😞.

Although I attempted to coordinate things with the sunny intervals, I failed.

I was going through the colony for the third time (trying to find the unmarked Q) when the rain arrived. The wind got even stronger, visibility plummeted and the bees and I got soaked.

I gave up in disgust, kicking myself for not starting earlier in the day.

I'll try again tomorrow.

On a slightly more positive note, the 'aggressive' swarm was no worse when the squall whipped in from the West, so perhaps they're not so bad after all.

The moral of this tale? Don't believe the Met Office weather forecast 😉 … and remember that the development of honey bee larvae and pupae is fixed.

So, three queens in a hive, three swarms in a week, three additional queens showing the importance of grafting young larvae … and three attempts to find an unwanted queen.

Good things come in threes (which was another title I considered and rejected).

Happy beekeeping.

Why not sponsor The Apiarist?

Sponsors of The Apiarist receive a newsletter on the science, art, and practice of sustainable beekeeping every week, at least 50% of which are for sponsors only. Sponsorship supports my research and writing and costs about the same as a coffee and doughnut a month, or less annually … go on, you know it makes (and it's healthier)

Notes

Stop press

- One week later there are still at least two queens present (the white and yellow ones) and lots of eggs in the 'three queens' hive.

- One week later the unpleasant swarm had decided they didn't like the queen, so appear to have done away with her. Queen cells and even more aggression were the result 😞.

Don't forget to contribute to the survey on absconding swarms. Further details are available in the post Absconding swarms and Citizen Science.

There's a new Tags page (under construction) to help find content in the extensive back catalogue a little easier. This page is also listed in the top navigation menu.

{{1}}: This isn't cooking the books to claim lower winter losses, but good bee management. It would have been even better if I'd united them before treating with miticides and feeding colonies for the winter 😞.

{{2}}: Again, not definitive, but a colony is unlikely to swarm unless there are sexually mature drones available. If they do, and there aren't, the parent colony will probably die, and the chances of the swarm surviving are already less than 25%. In contrast, supersedure costs nothing other than a new queen, and if she doesn't get mated it will not be a disaster.

{{3}}: I wanted larvae for grafting in mid/late May.

{{4}}: In my defence, the previous colony inspections had been relatively cursory.

{{5}}: Depending on how fast you read.

{{6}}: Remember, adults emerge or eclose, eggs hatch.

{{7}}: There are all sorts of epigenetic changes happening within the developing pupa which defines how queen- or worker-like the eventual queen is … all are queens i.e. they can mate and lay fertilised eggs, but the more queen-like ones are better, e.g. laying more eggs.

{{8}}: Though this is also dependent upon the genetics of the strain, a native dark queen fed since hatching on royal jelly may be relatively small when compared to other strains fed for less time.

Join the discussion ...