Being cruel to be kind

You'll have probably seen a number of different figures quoted for the maximum egg laying rate of a queen during late spring or early summer. One thousand eggs per day, 1,500+, 2,000 or more, or perhaps 'her own weight in eggs per day' {{1}}. Most of these eggs hatch and develop into workers. The number of bees in the hive is determined by the:

- Number of eggs laid by the queen per day

- Proportion of the eggs that hatch, develop and emerge

- Longevity of the emerged adult bees

I discuss all this in excruciating detail in a previous post.

Dying like flies?

One of the points I made was that (summer) worker bees tend to have shorter lives than most beekeepers think. The oft quoted 'workers live 6 weeks, 3 weeks as nurse bees and 3 as foragers', overestimates the average lifespan of workers, ~50% of which die within 3 weeks of emergence, and ~90% within 6 weeks.

Whatever the precise numbers, in a hive at 'steady state' (i.e. the population is neither increasing or decreasing), the same numbers of workers a day die as eggs are laid by the queen {{2}}.

And, in mid-season, that's a lot of bees (or eggs).

If you look on the ground at the hive entrance you'll often see dozens (or hundreds) of corpses … workers that have died in the hive and been removed by the undertaker bees. This always looks worse in poor weather, when the undertakers travel only a short distance before ditching their cargo. It's likely that at least as many workers die out foraging.

Live fast, die young …

Sponsors get more … posts, news, and information on the science, art, and practice of sustainable beekeeping. They also have access to over a decade of legacy posts, and ensure The Apiarist continues to appear every week.

Varroa monitoring

With a few notable exceptions {{3}}, if you've got bees, you've also got Varroa mites.

Varroa numbers increase when developing brood is available for the mite to reproduce on, meaning that levels rise throughout the season, usually peaking in late summer as the queen's laying rate reduces.

Although there's some variation, it's typically assumed that only ~10% of mites are present on adult worker bees — the so-called (and incorrectly named) phoretic stage in the life-cycle — with the remainder being hidden in capped cells, busily munching away on developing brood.

With reducing amounts of brood available for the mite to parasitise, phoretic mite levels increase massively.

This is a problem because it's at this time of the season that the long-lived winter bees are being reared. High levels of phoretic mites increase the probability that these developing winter bees will be parasitised, leading either to their death or — later, but no less damagingly — shortening their lifespan.

Colonies that 'run out' of bees in midwinter are almost inevitably doomed, and Varroa remains responsible for the vast majority of winter losses experienced by beekeepers.

Responsible beekeepers therefore monitor mite numbers periodically through the season, if levels appear too high there's always the option to apply an appropriate miticide.

Monitoring can be as unintrusive as sliding a tray under the open mesh floor for a few days and guesstimating the Varroa levels from the 'mite drop'.

Guesstimate, or worse?

Guesstimate because this is an inexact science — to put it mildly — but it's better than nothing.

Sacrifice of the few for the many

Alternatively, a cupful of worker bees are harvested from a brood frame, and treated in a manner that dislodges the attached Varroa.

If you know the number of bees in the cup (~300), and count the dislodged Varroa, you have a reasonably accurate indication of the phoretic mite levels in the hive. Depending upon the time of the season, and the phoretic mite level, this enables decisions to be made about whether intervention is needed {{4}}.

So, how do you dislodge the Varroa that are clinging tightly to the worker bees in your cup? The three most frequently described methods involve:

- An alcohol wash (windscreen washer fluid is inexpensive and effective)

- Carbon dioxide (easily administered using a cyclists tyre inflater)

- Icing sugar

In each case, the sample of bees is shaken more or less vigorously {{5}} to dislodge the mites, the bees are separated from whatever the mites are now in, and the mites are counted.

If you use alcohol, the bees are killed almost instantly.

Many beekeepers baulk at doing an alcohol wash expressly because it is inevitably fatal for the bees.

However, let's have a bit of perspective here; the ~300 bees in a cup represent less than 1% of the population of the hive, and likely increases the daily bee mortality by perhaps ~20%.

This is an example of the sacrifice of the few for the benefit of the many.

This is an ethical concept where actions are judged on their overall outcomes. Yes, a few bees are killed, but if mite levels are increasing fast or are already too high, then not measuring them potentially risks the loss of the entire colony.

The greater good (saving the hive) is considered 'better' than the individual bees sacrificed.

I'll return to ethics shortly.

But first, is it necessary to kill the bees that are sampled?

Sugar, sugar

This was going to be the original title of the post, coupled with a discussion of the chorus of the 1969 hit by The Archies {{6}}, which has been my earworm while writing this post.

Beekeepers have tried all sorts of other ways to dislodge mites, in a sample of a cupful of bees … or, at a larger scale, within the hive.

From a pragmatic standpoint, to be useful, whatever is used must be readily available, and inexpensive.

If something is to be applied to a hive, rather than a cupful bees not destined for return, it must also be non-toxic.

Icing sugar (which is sometimes called powdered sugar) works, and exhibits the necessary characteristics. You can purchase it from the supermarket, it's relatively inexpensive, and — being sugar — it is considered non-toxic for bees {{7}}.

In fact, bees eat the stuff.

If you shake a cupful of bees in icing sugar, and separate the sugar/mite mix from the bees, you'll notice that the bees are still 'alive and kicking'. These bees can be returned to the hive, so avoiding sacrificing 'the few for the many'.

For this reason, the sugar shake is favoured by some beekeepers for routine mite monitoring.

It allows the mites to be counted and doesn't kill the bees.

At least, that's the assumption.

Sugar dusting

Since mites are dislodged from bees by shaking a cupful of them with icing sugar, it's not a huge leap to scale the treatment up and apply powdered sugar to the hive. If you do this (and it's not too humid, which can result in a horrible sticky mess) then mites are dislodged and fall through the open mesh floor.

Randy Oliver has a good discussion about sugar dusting as a means of mite control. Start here, and then look at the final part of the 3-part series. I'm not going to rehash this topic as Randy's thoroughly covered it in those posts.

Icing sugar certainly dislodges phoretic mites, but has no activity against mites in capped cells (or residual activity against mites that emerge in the days after treatment {{8}}). Regular (weekly, or more frequently) dusting with 1 cup (~100 g) of icing sugar was used in these studies. Randy has a calculator that models the impact of regular sugar dusting, but concludes “We have not used sugar dusting for some years, since we did not find it to be cost effective for us.”.

Jamie Ellis has also looked at sugar dusting as a means of mite control (Ellis et al., 2009) and concludes:

Within the limits of our study and at the application rates used, we did not find that dusting colonies with powdered sugar afforded significant varroa control.

None of which means that beekeepers have stopped using this strategy {{9}}. It needs to be used very regularly to have any impact (and, even then, not enough to be worthwhile), and there must be risks of tainting honey stores with the continued application of sugar.

But let's go back to what happens to the bees …

If you want to avoid the AI 'slop' that increasingly contaminates beekeeping websites then please consider supporting The Apiarist. Sponsors ensure the continued existence of the site, and receive regular sponsor-only content. ChatGPT has never opened a hive or counted Varroa, so why trust its judgement when seeking information (or entertainment) on the science, art, and practice of sustainable beekeeping?

The fate of bees in a sugar shake

What happens to the bees shaken with icing sugar after they are added back to the hive?

Broadly, there are three possible outcomes:

- They live fulfilling lives as nurses and foragers, with no reduction in longevity.

- They die off appreciably faster, though not immediately, than similarly-aged untreated workers.

- All die within a short period after their return to the hive, either from direct exposure to powdered sugar, or the responses of their nestmates to them being coated in powdered sugar.

The assumption, by many who advocate sugar shake (for Varroa counting), is that the bees survive as well as those not treated with icing sugar (i.e. the first outcome).

So, which is it?

A recent paper by Selina Bruckner and colleagues has investigated this by using a mark-release-recapture experiment (Bruckner et al., 2025).

The rational is straightforward. A sample of 900 bees were collected, anaesthetised by chilling, and marked with one of three different colours (one for each of the treatments). For each treatment, 300 bees were used (all marked with the same colour), then released back into the hive. Five days later, every frame was digitally photographed, and the marked bees detected and counted.

The three treatments compared were; 1) shaking in powdered sugar, 2) gently coating in powdered sugar, and 3) nothing (the control). The second treatment allowed any toxicity — direct or indirect — of sugar exposure to be determined.

They additionally conducted alcohol washes on the samples to determine the efficiency with which the treatments dislodged any phoretic mites.

A total of 18 colonies were tested in this way, providing some statistical rigour to the results.

And the winner is … !

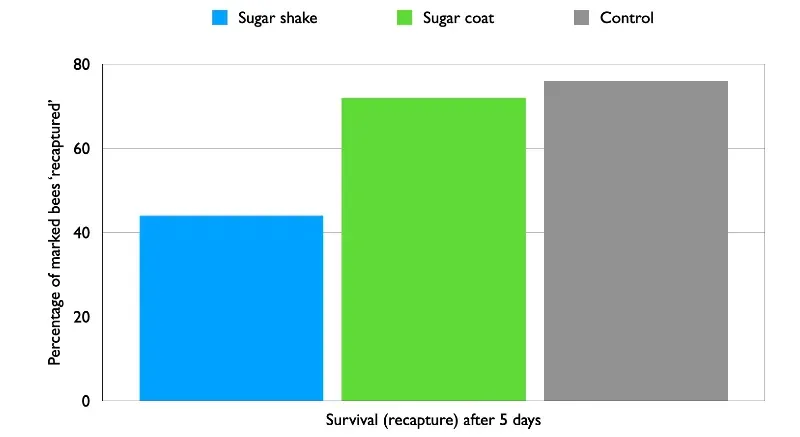

There was no statistical difference between the percentage of bees recaptured after 5 days that were in the sugar-coated (72%), or control (76%) groups. This shows that the sugar-coating alone did not adversely affect honey bee survival {{10}}.

Is ~25% loss over 5 days reasonable? It sounds like a lot. If you consider the figures I quoted earlier, with ~90% loss within 42 days, it suggests that the losses should be closer to 10%. One possibility is that some bees weren't recaptured because they were out foraging.

In comparison to these figures, only ~44% of the bees treated with a sugar shake were 'recaptured' after 5 days. This is a significantly smaller number, suggesting that the combination of powdered sugar and shaking is detrimental to bee survival.

The fate of the bees was not recorded (or investigated), but it is unreasonable to propose that a sugar-shake induces foraging (meaning they would not be recaptured) … remember, the simplest conclusion is usually the correct one.

Don't make it more complicated than it needs to be.

The conclusion from this part of the study is that a sugar-shake, undertaken as a means of quantifying Varroa, results in the bees that are exposed to the sugar dying faster than they otherwise would have done {{11}}.

The authors claim that the sugar-shake was 'highly variable' when compared to the gold standard alcohol wash for Varroa counting. This is based upon recovery efficacies for the sugar-shake of 67–100%.

However, I'm not entirely convinced by this interpretation … the lowest recoveries tended to be on samples containing few mites, where variation by one or two mites introduces big changes in efficacy. Overall the efficacy was a respectable 94%. On samples containing >10 mites (i.e. enough to exceed the 3% threshold at which treatment should be considered), the sugar-shake averaged ~98%. That's good enough for me.

Make up your own mind, the paper is Open Access, so free to download and read. Fill yer boots!

Back to ethics

Previous studies that have suggested that some powder treatments are detrimental for bee health. This recent paper is straightforward, internally controlled and easy to interpret.

Sugar-shake is favoured by those who think that it “doesn't kill the bees”.

It does.

I don't like killing bees, but I think it's probably more ethically acceptable to kill them quickly rather than returning them to the hive where they subsequently die faster.

Of course, that statement makes a number of implicit assumptions.

For example, it probably assumes that the ~50% that die within 5 days suffer in some way.

Do they?

I certainly don't know, and I've read some of the literature on pain detection and sentience in honey bees.

What if they suffer no pain, and remain blissfully unaware of their impending early demise?

In that case you could argue it's better to allow ~50% of the bees to enjoy a further 5 days of existence, rather than subjecting them to an alcohol wash.

More assumptions I'm afraid, including that they 'enjoy' doing whatever it is they're doing 😉.

About the only thing I can conclude is that it's risky to anthropomorphise too much … or at all.

Conclusions

A sugar-shake is a reasonably accurate way to quantify Varroa infestation levels on a sample ('cupful') of bees, to determine whether miticide treatment is necessary. However, it's only dependably accurate on heavily infested colonies, so less good if you're after advance notice that mite levels are climbing, but not yet close to being dangerously high.

In damp weather or very humid conditions, icing sugar has a tendency to clump badly, making counts less accurate.

Bees treated to a sugar-shake do not die immediately, but will die at a significantly faster rate than untreated bees.

Taken together, I think this makes the alcohol wash a better way to count phoretic mites. Reproducible, quick, inexpensive, though undoubtedly immediately fatal for the bees.

Future work …

In my mind this study raises two further questions:

- Do colonies treated for Varroa using sugar dusting exhibit a higher rate of worker bee deaths?

- What happens to bees exposed to CO2?

On the first point, Ellis et al., (2009) state that treated colonies contain similar numbers of workers and brood.

This is encouraging, but far from definitive.

Sugar dusting can be used to kill open brood (it's one way of selecting larvae for the Hopkins method of queen rearing), so I would expect it to have some impact, perhaps depending on how the experiment was conducted. Worker survival really needs a mark-release-recapture study … queens with different laying rates might otherwise confound the results.

We regularly used CO2 to anaesthetise bees in the laboratory. It works well (i.e. kills few bees) in a controlled environment. However, an apiary is not the same as a laboratory. Dosage and duration of exposure likely influence survival.

I've also used CO2 for phoretic mite counts. When I tip the bees back onto the top bars of the hive it's noticeable that some are very mobile, while a few look moribund.

How well do these bees survive? Do they all survive?

Sometimes you have to be cruel to be kind, where the sacrifice of a few bees gives an early warning of a mite problem in the colony.

Prompt intervention then saves the colony.

Or you could ignore mite counts, mite levels and/or treatment and hope for the best … though the evidence from winter loss surveys suggests that this is not advisable.

Avoid surprises, count mites 😄

More like this?

That's over 3,000 words you've just read on bees and beekeeping. If you want more of this every week, then why not sign up as a sponsor of The Apiarist? At least 50% of posts are now for sponsors only, and sponsors ensure that there will be comprehensive, well researched and entertaining posts on sustainable beekeeping appearing every week.

Notes

Next week — for sponsors — repeated oxalic acid treatment … the good, the bad and the ugly. You'll hear it being widely recommended, but not by many people who have read the studies that have determined whether it works or not … and that's before the issue of whether it's even allowed is considered.

References

Bruckner, S., Williams, G.R., Tsuruda, J., and Underwood, R.M. Let’s not sugar coat it: the powdered sugar shake is not harmless for honey bee workers. Journal of Apicultural Research 0: 1–6 https://doi.org/10.1080/00218839.2025.2550855.

Ellis, A.M., Hayes, G.W., and Ellis, J.D. (2009) The efficacy of dusting honey bee colonies with powdered sugar to reduce varroa mite populations. Journal of Apicultural Research 48: 72–76 https://doi.org/10.3896/IBRA.1.48.1.14.

{{1}}: Large queens weigh ~200 mg and an egg weighs 0.12–0.22 mg, giving a range from ~900–1,600

{{2}}: For convenience I'm ignoring eggs that don't hatch, those that are cannibalised, workers that don't develop or eclose etc.

{{3}}: Remote areas of Northern Scotland, some islands etc., and if you're in any doubt then it's almost certain you already have Varroa.

{{4}}: 3% infestation i.e. 3 mites per 100 bees, so ~9 mites in a cupful of bees, is often considered the threshold indicating that immediate treatment is required.

{{5}}: There are studies on how vigorous the shaking needs to be effective. TL;DR More is better.

{{6}}: “Sugar, Ah honey, honey, You are my candy girl …” which must be about beekeeping.

{{7}}: I'm going to avoid a discussion of anti-caking agents added to powdered sugar as it's suggested that these are sometimes toxic for bees.

{{8}}: Which is relevant when compared with oxalic acid, which does remain active for a few days after application.

{{9}}: I'm regularly asked about it during winter talks on mite control or colony management.

{{10}}: We can conclude that bees aren't attacked or turfed out of the hive simply by being coated in sugar.

{{11}}: Why do they die faster? This wasn't addressed in the paper. Icing sugar is a very fine powder, with particles of ~20 microns in diameter. Since tracheal mites are 7–8 times this size, and can invade the trachea of honey bees, it seems possible that death is caused by impairing respiration. But that's a guess.

Join the discussion ...