Midwinter, no; mites, yes

There’s a certain irony that the more conscientious you are in protecting your winter bees from the ravages of Varroa in late summer, the more necessary it is to apply a miticide in the winter.

Winter bees are the ones that are in your hives now {{1}}.

They have a very different physiology to the midsummer foragers that fill your supers with nectar. Winter bees have low levels of juvenile hormone and high levels of vitellogenin. They are long-lived – up to 8 months – and they form an efficient thermoregulating cluster when the external temperature plummets.

Winter bees production

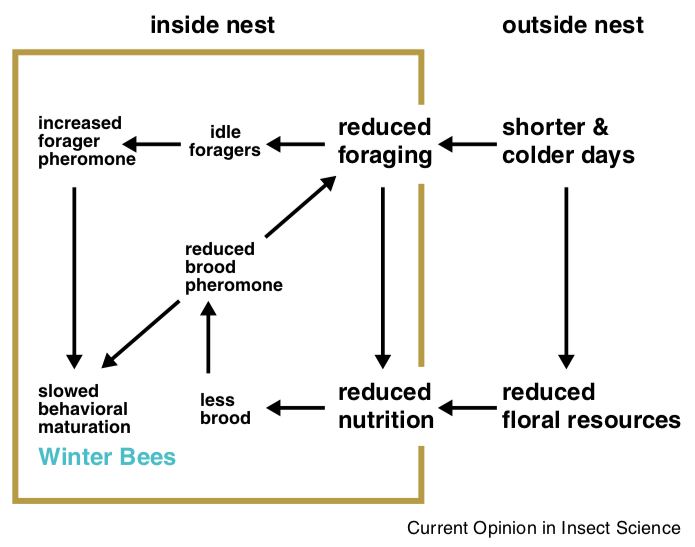

In the temperate northern hemisphere, winter bees are reared from late summer/early autumn onwards. The combination of reductions in the photoperiod (day length), temperature and forage availability triggers changes in brood and forager pheromones.

Together these induce the production of winter bees.

For more details see Overwintering honey bees: biology and management by Döke et al., (2010).

Day length reduces predictably as summer changes to autumn. In contrast, temperature and forage availability (which itself is influenced by temperature and rainfall … and day length) are much more variable (so less predictable).

All of which means that you cannot be sure when the winter bees are produced.

If there’s an “Indian summer“, with warm temperatures stretching into late October, the bees will be out working the ivy and rearing good amounts of brood late into the year. The busy foragers and high(er) levels of brood pheromone will then delay the production of winter bees.

Conversely, low temperatures and early frosts reduce foraging and brood production, so bringing forward winter bee production.

It’s an inexact science.

You cannot be sure when the winter bees will be produced, but you can be sure that they will be reared.

Protect your winter bees

And if they are being reared, you must protect them from Varroa and the viral payload it delivers to developing pupae. Most important of these viruses is deformed wing virus (DWV).

Aside from “doing what it says on the tin” i.e. causing wing deformities and other developmental defects in some brood, DWV also reduces the longevity of winter bees.

And that’s a problem.

If they die sooner than they should they cannot help in thermoregulating the winter cluster.

And that results in the cluster having to work harder to keep warm as it gets smaller … and smaller … and smaller …

Until it’s so small it cannot reach its food reserves (isolation starvation) or freezes to death {{2}}.

So, to protect your winter bees, you need to treat with an appropriate miticide in late summer. This reduces the mite load in the hive by up to 95% and so gives the winter bees a very good chance of leading a long and happy life 😉

I discussed this in excruciating detail in 2016 in a post titled When to treat?.

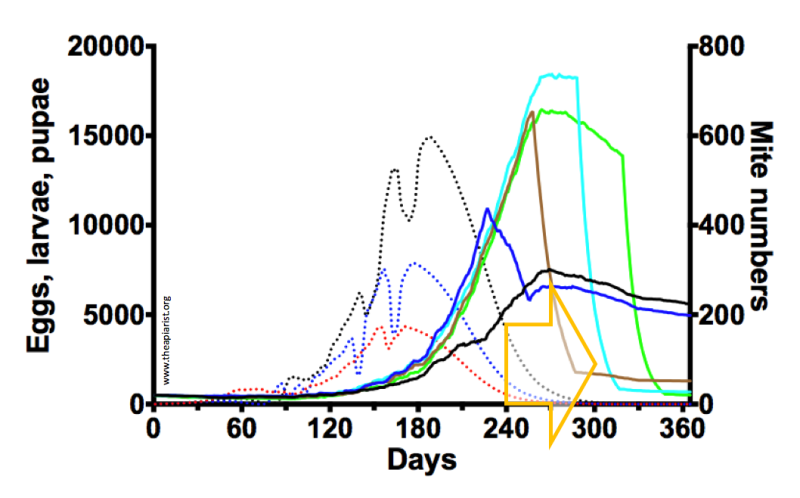

The figure above was taken from that post and is described more fully there. The arrow indicates when winter bees are produced and the variously coloured solid lines indicate mite numbers when treated in mid-July to mid-November.

The earlier you treat (indicated by the sudden drop in the mite count) the lower the peak mite numbers when the winter bees are being reared.

Note that the mite numbers indicated on the right hand vertical axis are not ‘real’ figures. They depend on the number present at the start of the year. In the figure above I “primed” the in silico modelled colony with just 20 mites. This will become very important in a few paragraphs.

Late season brood rearing

Compare the blue line (mid-August treatment) with the cyan line {{3}} (mid-October treatment) in the figure above.

The mid-October treatment really hammers the mite number down and they remain low until the end of the year {{4}}.

The reason the mite numbers remain low after a mid-October treatment is that there is little or no brood being reared in the colony during this period.

Mites need brood, and specifically sealed brood, to reproduce on.

In the absence of brood the mites ‘colony surf‘, riding around as phoretic mites on nurse bees (or any bees if there aren’t the nurse bees they prefer).

And that late season brood rearing is the reason the end-of-year mite number for the colony treated in mid-August (the blue line) remains significantly higher.

Mites that survive the miticide in August simply carry on with their sordid little destructive lives, infesting the ample brood available (which could even include some highly mite-attractive and productive drone brood) and reproducing busily.

So, the earlier you treat, the more mites remain in the hive at the end of the year.

Weird, but true.

Early season brood rearing

The winter bees don’t ‘just’ get the colony through the winter.

As the day length increases and the temperature rises the colony starts rearing brood again. Depending upon your latitude it might never stop, but the rate at which it rears brood certainly increases in early spring.

Or, more correctly, in mid- to late-winter.

And it’s the winter bees that do this brood rearing. As Grozinger and colleagues state “Once brood rearing re-initiates in late winter/early spring, the division of labor resumes among overwintered worker bees.”

Some winter bees revert to nurse bee activity, to rear the next generation of bees.

And this is another reason why strong colonies overwinter better … not because they (also) survive the cold better {{5}}, but because there are more bees available to take on these brood rearing activities.

Strong, healthy colonies build up better in early spring.

Colonies that are weak in spring and stagger through the first few months of the year, never getting close to swarming, are of little use for honey production, more likely to get robbed out and may not build up enough for the following winter.

Midwinter mite treatments

Which brings us back to the need for miticide treatment in midwinter.

The BEEHAVE modelled colony shown in the graph above was ‘primed’ at the beginning of the season with 20 mites. These reproduced and generated almost 800 mites over the next 10-11 months.

What do you think would happen if you start the year with 200 mites, rather than 20?

Like the 200 remaining at the year end when you treat in mid-August?

Lots of mites … probably approaching 8000 … that’s almost as many mites as bees by the end of the season.

So, one reason to treat in the middle of winter is to reduce mite levels later in the season. The smaller the number you start with, the less you have later.

But at the beginning of the season these elevated levels of mites could cause problems. High levels of mites and low levels of brood is not a good mix.

There’s the potential for those tiny patches of brood to become mite-infested very early in the season … this helps the mites but hinders the bees.

Logically, the more mites present at the start of brood rearing, the more likely it is that colony build up will be retarded.

So that’s two reasons to treat with miticides – usually an oxalic-acid containing treatment – in midwinter.

Midwinter? Or earlier?

When does the colony start brood rearing again in earnest?

This is important as the ‘midwinter’ treatment should be timed for a period before this when the colony is broodless. This is to ensure that all the mites are phoretic and ‘easy to reach’ with a well-timed dribble of Api-Bioxal.

In studies over 30 years ago Seeley and Visscher demonstrated that colonies have to start brood rearing in midwinter to build up enough to have the opportunity to swarm in late spring. These were colonies in cold climates, but the conditions – and season length – aren’t dramatically different to much of the UK.

Low temperatures regularly extend into January or February. The temperature is also variable year on year. It therefore seems (to me) that the most likely trigger for new brood rearing is increasing day length {{6}}.

I therefore assume that colonies may well be rearing brood very soon after the winter solstice.

I’m also aware that my colonies are almost always broodless earlier in the winter … or even what is still technically late autumn.

This is from experience of both direct (opening hives) or indirect (fresh brood mappings on the Varroa tray) observation.

Hence the “Midwinter, no” title of this post.

Don’t delay

I therefore treat with a dribbled or vaporised oxalic acid-containing miticide in late November or early December. In 2016 and 2017 it was the first week in December. Last year it was a week later because we had heavy snow.

This year it was today … the 28th of November. With another apiary destined for treatment this weekend.

If colonies are broodless there is nothing to be gained by delaying treatment until later in the winter.

Most beekeepers treat between Christmas and New Year. It’s convenient. They’re probably on holiday and it is a good excuse to escape the family/mince pies/rubbish on the TV (delete as appropriate).

But it might be too late … don’t delay.

If colonies are broodless treat them now.

If you don’t and they start rearing brood the mites will hide away and be unreachable … but their daughters and granddaughters will cause you and your bees problems later in the season.

Finally, it’s worth noting that there’s no need to coordinate winter treatments. The bees aren’t flying and the possibility of mites being transferred – through robbing or drifting – from treated to untreated colonies is minimal.

{{1}}: Assuming you’re not one of the 3% of readers from the Antipodes.

{{2}}: Or, as I’ll discuss shortly, it staggers through the winter but isn’t strong enough to build up properly in early spring … but I’m getting ahead of myself.

{{3}}: At least, I think it’s cyan … I’m colourblind.

{{4}}: However, although it’s difficult to tell from the figure, the mite numbers at the year end are actually a bit higher than it started the year with (I’ll return to this shortly).

{{5}}: Because they’re better at thermoregulation and because they use food reserves more economically.

{{6}}: I don’t know if this has formally been tested.

Join the discussion ...